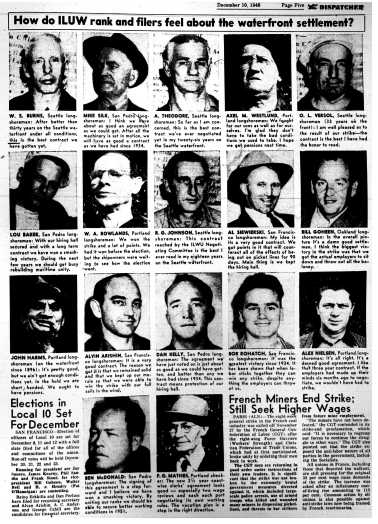

Dispatcher December 10, 1948. Click to enlarge

This prize-winning report is presented in two parts:

Part 1: The confrontation takes shape

Part 2: Ninety-five days to victory (this page)

Ashley Lindsey's article won the 2013 Library Research Award given by University of Washington Libraries and the Best Paper Award given by the UW Department of History

by Ashley Lindsey

The 1948 West Coast maritime strike effectively shut down the West Coast shipping industry for 95 days, and included a coalition of the ILWU, the Pacific Coast Marine Firemen, Oilers, Watertenders and Wipers Association (MFOW), Marine Engineers Beneficial Association (MEBA), Marine Radio Officers of the American Radio Association (ARA), and the National Union of Marine Cooks and Stewards (NUMCS).[1] Negotiations on the ILWU’s longshore contract had begun before it came up for renewal in June of 1948, and a vote showed 94.34% of longshore workers favored renewal. The WEA originally asked for a 30-day contract as opposed to the typical one-year contract, but eventually agreed to a renewal, under the condition that either side could give notice of cancellation if done so before the contracts with the other unions were decided.[2] With anti-labor legislation in the works, the agreement allowed both sides to wait for Congress before agreeing to a contract.

The Taft Hartley Act, which passed on June 23, 1947, altered the status quo significantly. One of the provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act outlawed the closed shop, which included the ILWU’s hiring hall. On February 13, 1948, Frank P. Foisie, as President of the WEA, sent a letter to the ILWU expressing his desire to start negotiations earlier than the April 15 deadline for notification to change the contract, in order to allow enough time for the agreements to be brought into conformation with the Taft-Hartley Act before the contract expired on June 15.[3] This meant that the hiring hall would no longer be allowed to operate under union authority, and specifically that the contract could no longer require preference of employment for union members, the presence of a union-elected dispatcher, or the ability of the union to deny registration to longshore applicants.[4]

The attack on the hiring hall infuriated the ILWU membership and was immediately equated to a return to pre-1934 conditions like the shape up and fink hall. Harry Bridges received a memo from the union’s Research Department advising, “the most useful thing that we can do in this connection is to dig out analogies between the ship owner proposals and the situation which existed before 1934,” and it seems he took the advice.[5] This framing is evident in a letter sent out from the Coast Negotiating Committee to a local stating, “…we have concluded that the employers’ answer leaves little room for doubt that they intend to seek sweeping changes in the hiring hall, which, if successful, would leave us with the pre-1934 fink halls, or a roof over the pre-1934 shapeup.”[6] On March 24, 1948 the ILWU responded, setting forth a position on a jointly operated hiring hall, but not compromising on the hiring hall’s dispatcher being elected by the union.[7] Joint negotiations began, and quickly reached a stalemate, even when the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service stepped in to help facilitate the talks.[8] Although there were other issues besides the hiring hall, the union was unwilling to see it dismantled. Employers stated, “…discussion of matters other than conforming to the new law [Taft-Hartley] are postponed because no contract can be written that does not conform to the law.”[9]

Taft-Hartley injunction

The Dispatcher , June 25, 1948, p2.

The recently enacted Taft-Hartley Act gave the President the power to stop a strike or lockout for up to ninety day s..

With no end in sight, and the June 15 deadline for settlement quickly approaching, on May 13 the ILWU took a strike vote in case no agreement could be reached.[10] Following a recommendation of a ‘yes’ vote by the ILWU’s Coastwise Longshore Caucus on the two issues of authorizing a strike if employers insisted on dismantling the hiring hall, and striking with the other maritime unions and staying on strike until all unions reach satisfactory agreements, the membership voted 89.41% ‘yes’ on the first, and 88.95% ‘yes’ on the second.[11]

President Truman appointed a Presidential Board of Inquiry to look into the situation on June 7 and 8. It determined that a strike would in fact occur, and that the situation constituted a national emergency.[12] A series of restraining orders were issued beginning June 14, and on July 2, a temporary injunction was issued for the remaining balance of the 80 days, as provided for under the Taft-Hartley Act.[13]

Having already authorized and begun preparations for a strike, the union lobbied against an injunction, viewing it as a tool of the employers to take away their right to strike.[14] Once the injunction went into effect, a work slowdown began in protest. Employers charged that some Northwest ports operated at half speed or less, and stated before the Pacific Coast Section Board of Inquiry that the union had, “embarked upon a course of conduct designed to disrupt shipping operations and to stultify negotiations, it being their apparent purpose to defeat the injunction and discredit the law under which [the injunction] was issued.”[15]

Although the Attorney General of the United States never stepped in and ruled as such, evidence suggests that the ILWU and other maritime unions did, in fact, conduct a slowdown that constituted an “interference with the orderly continuance of work,” prohibited under the Taft Hartley injunction rules.[16] Slogans distributed to workers encouraged them to make the period of the injunction difficult on the employers. One such slogan stated, “For eighty days we are in a deep freeze, to cool off, if you please. But when things get cold, they slow up too, so ask yourself, who’s screwing who?”[17] Another was more directly hostile to employers: “Hear the complaint of Fink-Hall Foisie, work’s slowing down and the party’s getting noisy. Listen to the old Fink groan and wheeze, but while you listen, cool off in the breeze.”[18] These slogans not only demonstrate the existence of an orchestrated slowdown, but also the hostility towards Taft-Hartley and employers. The 80 days, meant to calm the situation and facilitate negotiations, did not go as planned. Although negotiations were being conducted through the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, neither side was moving on the hiring hall issue.

“Government by the Shipowners,” The Dispatcher, June 11, 1948, p2.

Then, it seemed, there was hope for settlement. On July 29, the union submitted a proposal for renewing the hiring hall clause as it existed, but with the condition that this could be altered pending determination of legality by court of last resort, which was rejected by the WEA.[19] However, by August 5, an agreement was signed by employers independent of the WEA.[20] Pressure increased as the end of the injunction neared and the deadline for strike action on September 2 approached. After secret meetings between Bridges and Foisie, the negotiations were reopened at the end of August, and an agreement on the hiring hall was within reach.[21] The proposal submitted on July 29 was modified to change the ‘court of last resort’ to the decision of any court on the hiring hall issue, at which point either side could ask to bring the issue up for discussion again.[22]

With the hiring hall issue put to rest, negotiations turned to wages and conditions, and with additional time, an agreement seemed within reach. However, this would not be the case. When the ILWU membership had voted to go on strike before the intervention of the injunction, they had also voted that the coalition of maritime unions would strike if any one union failed to reach a satisfactory agreement. With the NUMCS still at an impasse with their employers, the ILWU delayed agreement by demanding settlement on all issues, making an agreement unattainable.[23]

Members vote

As the last step in the government’s emergency prevention procedure, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) was to hold an election, and have the membership vote directly on the final offer of the employers, bypassing the leadership of the union.[24] The last offer by employers was essentially its original demands; its ten points included requiring the hiring hall dispatcher to be chosen by the director of the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service rather than elected by the union, no preference for union members in hiring, and a rule that required officers and agents of the union to notify employers before going on the docks to inspect grievances.[25]

The Dispatcher , September 3, 1948, p2.

Pamphlets and letters were sent to longshoremen trying to convince them to accept the offer and turn on their leadership, saying it was dominated by the Communist Party.[26] Foisie stated in a news release that “longshore union officials are without power to reject the employers’ last offer- that power rests with the longshoremen themselves under the law.”[27] The WEA seemed to hope that by bypassing the leadership, which tended to be more radical than the union membership as a whole, their demands would be met. One brochure reminded longshoremen, “Let’s be sure we know what we’re doing…[a strike will] cost everybody a lot of money. The very first thing to do is find out exactly why we’re in a strike- exactly what the situation was when your union officials put you on the bricks.”[28]

Perhaps it was part wishful thinking that the membership would settle for a contract to avoid what was predicted to be a long and difficult strike, or maybe the WEA recognized the political dissension within the ILWU in preceding years, and, amid the growing conservatism of the Cold War political climate saw weakness and an opportunity to secure a very self-beneficial contract.[29] Whatever the case, it was a miscalculation on the part of the WEA.

The NLRB held voting August 30 and 31, and in an act of protest, not a single ballot was cast by any of the 26,695 eligible workers along the entire West Coast.[30] Posters (Fig. 1) had been posted at every polling place, and an editorial in the union’s newsletter, The Dispatcher, described the NLRB as being “subverted to [employers’] favor and purpose.”[31] A second vote on the shipowners’ proposals was taken, this time by the ILWU. The two items on the ballot included a vote to accept the employers’ proposal, which was rejected by 96.8% of the membership, and a vote on whether the leadership of the union should sign anti-communist affidavits, another provision of Taft-Hartley, which was rejected by 94.39% of the membership.[32]

Strike begins

The strike officially began on September 2 at midnight, with the expiration of the 80-day injunction, and was confirmed by the vote rejecting the contract and affidavits soon after.[33]

Another AFL union accused of acting as a strike breaker was the ILA local in Tacoma. The situation became especially problematic when the U.S. Army required workers to unload vessels. Although the ILWU had offered to work the cargo under the old contract provisions, the WEA had refused, stating that it was not in the long term interests of the Army to support communists within the United States.[36] Needing the cargo unloaded, the army hired workers without going through the ILWU. Many of these vessels were diverted to the Port of Tacoma, where the ILA local was willing to work the cargo, despite having told the ILWU that it would not.[37] The hostility between the Tacoma ILA and the ILWU is evident in the lyrics of a song written for the strike:

Did someone dump you on your pratt because you’re such a fink?

Or did they diaper you with fly paper on account of how you stink?

Isn’t there enough work in Tacoma to keep all you girls together?

…Cause by then you’ll know what a strike is

And you’ll know where a fink comes in

And you’ll go your way and you will say

Nevermore will I ever sin.[38]

Seattle Post-Intelligence September 14, 1948.

When the ILWU refused to unload ships carrying military cargo, the potential for government intervention escalated. Click to read articles.

The Army’s hiring of strikebreaking workers known as “scabs” was met with violence and picketing; in San Francisco, a fight over Army work resulted in both a scab and a striker being stabbed and hospitalized.[39] After picketing by the ILWU, the Army eventually began hiring union members through employers not affiliated with the WEA.[40] The press’s reaction to violence during the strike varied. For example, while the Seattle Post-Intelligencer titled an article, “Sailors Fight Longshoremen on Calif. Pier,” implying that the SUP instigated the violence by engaging in strikebreaking, the Los Angeles Times coverage of the longshore presence at a CIO oil workers’ strike that erupted in violence was much more negative, describing them as a mob, and later, in an opinion piece as “intruding,” “rowdy,” and communists trying to take control of the oil industry.[41] Regardless of which way the coverage leaned, the focus was on the length and the impact of the strike on the public.[42]

It is important to note that much of the strikebreaking was done by workers within organized labor. Towards the end of the strike, the SUP demanded that the WEA give them jurisdiction over unloading certain cargoes that traditionally belonged to the ILWU.[43] Although they were ultimately unsuccessful, the attack demonstrated the fractured nature of U.S. labor. The actions of unions with different, more conservative organizational philosophies foreshadowed the attacks the ILWU would face in the Cold War.

The growth of Cold War political sentiments was reflected in the WEA’s strategy during the 1948 strike. It staunchly proclaimed it “[could not] do business with irresponsible Communist Party line leadership,” and that negotiations would not happen with an ILWU leadership that refused to sign the anti-communist affidavits.[44] With the most recent vote of the union supporting his refusal to sign the anti-communist affidavit, Bridges was unwilling to back down. Once negotiations were off, the strike quickly became a political war between employers and the leaders of the ILWU.

Due to the political nature of the strike, both sides tried desperately to shape public opinion. The strategy used by the WEA was to paint Bridges and other leaders as “reds,” to highlight the hardships the strike was causing, and to paint the union’s leadership as dictatorial. According the ILWU, the employers spent thousands of dollars in propaganda via mediums such as newspapers, fliers, and radio.[45] The red-baiting done on the behalf of the WEA was meant to play up the growing Cold War political sentiments, including the fear of communism. One advertisement put out by the employers was entitled, “Which Flag Do We Fly?,” and showed two flags, a Soviet flag and an American flag, implying that the employers represented American interests while the ILWU represented the interests of communism and the Soviet Union.[46] Another showed a photograph of Bridges drinking with Soviet official Vyacheslav Molotov, and included quotes from Bridges that painted him in a radical and totalitarian light, despite the fact that employers had been present at the event as well.[47] With the hiring hall issue tabled pending a court ruling, the issue in the strike that mattered most to the employers was the removal of the radical left-wing leadership.

The longshore industry’s location in global and national trade caused a work stoppage to impact the public in a drastic way. Employers hoped to use this against the ILWU when the public began feeling the effects of goods not coming in or going out of the ports.[48] Playing up the fear of shortages, an employer news release stated, not even a month into the strike, that there was already a shortage of “imported essentials.”[49] An advertisement run by the WEA compared the disruption of shipping to a phone service going dead or a grocery store being closed. Blaming the disruption on the irresponsible leadership of the ILWU, the employers encouraged the public to exercise their rights as Americans and demand improved service.[50] There was also a fear that Alaska and Hawaii, which employers’ described as “entirely dependent” on West Coast shipping for supplies, would be hurt by the strike. A cartoon of Joseph Stalin and Bridges sitting atop barrels of supplies, while surrounded by starving Berliners and Hawaiians, shows how the fear of shortages converged with the fear of communism. This intersection, also seen in a flier entitled “This is our Berlin, Mr. Truman,” connected the strike to the Berlin Blockade, which was contemporaneous with the strike, and provided a convenient comparison between the communists keeping supplies from Berlin, and the ILWU leadership keeping supplies from the West Coast.[51] By tying in the fear of communism with the public desire for consumer goods, the publicity campaign hoped to blame the union for any shortages, and consequently turn public opinion against the union.

Listen to Labor Radio 1948

Reports from Labor was a fifteen-minute, biweekly labor Seattle radio show started during the strike by Jerry Tyler, a Marine Cooks and Stewards Union activist. In the photo above Tyler (center) sings with Trudy Kirkwood and Paul Robeson . See Leo Baunach's article, Seattle's CIO Radio: Reports from Labor.

Here is the December 3, 1948 Reports from Labor broadcast announcing victory and end to the strike. Tyler interviews MCSU and ILWU rank and file members (pdf transcript) . Listen to the 10 minute broadcast below.

(courtesy Ronald Magden):

The ILWU countered these publicity drives with its own campaigns. Many of the advertisements published by the employers were met with a counter-advertisement by the union. For example, in response to the “Which Flag do We Fly?” flier, the union countered with its own version, but instead of having the American and Soviet flags, it showed a flag with a dollar sign and the American flag. Below the flags, a description listed the actions taken by maritime unions to support the war effort, contrasted with the ways in which the employers profited from the war.[52] In addition to the counter-advertisements, the Joint Action Committee, comprised of members from the various maritime unions on strike, ran an offensive publicity campaign focusing on the unions’ willingness to negotiate and the employers’ failure to meet them halfway.[53]

In several cities radio programs were used by the unions to get their message out to the general public.[54] In Seattle, Marine Cooks and Stewards activist Jerry Tyler hosted a ten-minute program that he called "Reports from Labor." It was popular enough that CIO unions in the region decided to make it permanent. Tyler stayed on the air until the red scare and Korean War forced him off two years later.

Rank-and-file union members also went to speaking engagements at community gatherings, such as business associations, political groups, and church services.[55] Demonstrations were another important part of creating publicity. Aside from the standard picketing that occurs during a strike, these actions allowed the unions to raise public awareness, spread their message and increase the visibility of the strike. On one occasion in San Francisco, union members marched to the WEA headquarters and demanded to negotiate. When they found the building guarded by police, the union members passed out fliers and used a loudspeaker to argue their case before the hundreds of onlookers, creating an image of an obstinate employer unwilling to compromise, and therefore effectively placing the blame for the closed ports on the WEA.[56]

Negotiations

By the end of October, following two months of red-baiting and heated disputes, the situation on the waterfront had reached a stalemate. Bridges had predicted a long and difficult strike when he stated, “when the smoke clears away we might have a union and they won’t have an association. Or vise versa.”[57] As time passed, the pressure increased for a settlement. Then, on November 6th, four days after the Presidential election in which Truman, to the nation’s surprise, defeated both Dewey and Bridges’ favored Wallace, negotiations restarted.[58]

Openness to negotiations signaled a “new look” from employers, and an openness to mutual cooperation that had not existed on the waterfront in over fourteen years. In late October, a union advertisement had noted that the “directors of the WEA are having one hell of a time keeping their own people in line with the lousy policy they are following.”[59] A quote from Randolph Sevier of the Matson Navigation Company, a member of the WEA, confirms infighting within the organization as the strike dragged on; “I couldn’t stomach it any more…‘I said to Cushing [President of Matson], ‘…Regardless of what we may think of Bridges and his crowd, the law says we’ve got to business with them. Why don’t we cut out the flag-waving and start doing so?’”[60]

The WEA turned on Foisie and its other seasoned leaders, and talks commenced with a new, fresh set of negotiators willing to cooperate with the ILWU. According to a union radio program, the “atmosphere in the preliminary meeting was excellent. The employers are pledged to good faith negotiations, and no cute tricks. Foisie, Harrison, and Plant…are most conspicuous by their absence.”[61] Under what was known as the “Roth Formula,” the CIO and the San Francisco Employers Council participated in negotiations in order to help facilitate talks and to assure that both sides abided by the agreement reached.[62] By the 11 November, the hiring hall issue had been laid to rest. It would remain a union-controlled closed shop, unless a court of last resort found it illegal, and while employers got to have representatives in the hall, the dispatcher would remain solely elected by the union.[63]

New accord

After 95 days on strike, a final agreement was reached on November 26.[64] The agreement signaled that “after years of trying to break the union, [the WEA] had resolved to try living with [the union] in peace.”[65] Lasting for three years rather than the typical one meant that both sides were comfortable enough with the tenets of the agreement to sign for an extended period of time, representing a new level of cooperation and security within the industry.[66] Additionally, there was a provision barring strikes or work stoppages during the contract’s term. Grievances would be addressed by a new, comprehensive system of arbitration, including a jointly chosen coast wide arbitrator with the power to make a final decision on any conflict.[67] Other contract provisions included annual wage adjustment opportunities, a 16 cent wage increase, decreased shift lengths from ten to nine hours, and earned vacations.[68] When the contract went to the membership for approval, all but four locals unanimously voted in favor of accepting the contract.[69]

The 1948 strike was not so much a loss for employers as a shift in policy. What elicited such a complete reversal from the WEA policy early in the strike of not negotiating with communists to a completely new, cooperative approach? The most immediate cause was Truman’s victory over Dewey. Since Dewey had been favored in the polls, the employers were hoping that a conservative in the White House who considered Bridges a communist would aid their cause.[70] His loss was a sign that the political climate in the United States had not shifted as far right as they had anticipated. The employers also found themselves losing the battle for public opinion.[71] Because the union had publicly advertised its willingness to negotiate, the strike was easily blamed on the WEA for refusing to meet it halfway. The public’s sympathy towards the union is evident in donations and financial support made to the union during the strike. In the San Francisco area alone, over $20,000 worth of food contributions and $4,813.12 in monetary contributions, ranging from $.10 to $150, were made by members of the public to striking workers to help ease the financial difficulties imposed by the strike.[72] Leeway in paying bills and rents was another way the public showed support, and one car dealer even put out an advertisement stating, “It’s been tough going…‘Buy your car now and make no payments until 30 days after you go back to work!!”[73]

The economic pressures on the shipping industry also played a role in the decision of the WEA to change its course of action to be more accommodating to the ILWU. Decline in the amount of trade traveling through the ports was a major problem, and the WEA had traditionally taken the stance that the solution was to decrease labor costs.[74] Several months after the signing of the contract, a panel of employers and union members got together to discuss how to increase the health of West Coast shipping. At the meeting, Maitland Pennington of Pacific Transport Lines stated, “An unfortunate industrial relationship of the parties existed in the past. This is no longer true, and shippers must be made aware of this fact. Shippers must be assured that there will be no work stoppages….”[75] If strikes and work stoppages were driving away business, prolonging a bitter strike would only worsen the situation. Cooperation ultimately did help turn around trade; the years after the strike saw a steady increase in trade, in part due to the increased reliability of the West Coast ports.[76]

Dynamics of solidarity

The most important factor that led to the change in strategy was the inability of the WEA to convince the rank-and-file membership to turn on Bridges. Solidarity remained strong throughout the strike, with an average of less than two percent of the membership defecting during the strike (Table 1).[77] With large political divisions within the union and a union membership increasingly critical of Bridges, 1948 seemed the most opportune time for the employers to get rid of the man they had been fighting for fourteen years. Bridges’ home Local 10 of San Francisco had even elected an anti-communist president.[78] If there was so much dissension within the union, why, then, did the WEA find it so hard to exploit this? The answer lies with the ILWU’s form of exceptionally strong and active union democracy.

In Union Democracy Reexamined, Margaret Levi, David Olson, Jon Agnone, and Devin Kelly argue that the ILWU has a strong rank-and-file participatory democracy. Looking at the procedural requirements (direct voting on contracts and strikes, low threshold for recall of elected leaders, and local autonomy) and the presence of an organizational culture (rank-and-file participation, inclusion and fairness as values of the organization, membership defeating leadership on determining policy, and access to information) as criteria, we can examine the strength of ILWU democracy in 1948 and then determine what role it played in maintaining union solidarity throughout the strike. [79]

The procedural requirements of a participatory democracy were quite evident in the 1948 strike. First, the union had a tradition of voting on all decisions to go on strike or to accept a new contract, and each member got one vote, as provided for in the 1937 constitution.[80] This was seen in 1948 when the union voted to strike in May, rejected the final offer in September, and accepted the contract agreement in November. The ability to recall elected officials was also in the union’s constitution, and was used in the strike publicity as a counterpoint to the employers’ accusations that Bridges and the communists were ruling the waterfront like dictators.[81] Additionally, each local had institutional autonomy from the international union. For example, in 1943 the Portland, Oregon local refused to accept black workers into its union, and by doing so it contradicted the international’s policy of racial equality.[82] While this created a heterogeneous international when locals directed their own policy, the autonomy gave workers a sense of ownership in their union, and increased loyalty. This is evident in Portland, where not pressing the desegregation issue allowed the ILWU to maintain the local’s allegiance.[83] While autonomy allowed the locals to enact policies reflecting the beliefs of their members, the Portland example reflects how this could result in a tyranny of the majority. The leadership of the union chose to preserve the loyalty of the white workers and their exclusionary democracy at the cost of permitting racism to persist within union governance.

An organizational culture was also present in 1948. According to Union Democracy Reexamined, the period between the passage of Taft-Hartley in 1947 and the expulsion of the ILWU from the CIO in 1950 experienced significantly high levels of rank-and-file participation due to the external threats the union was facing.[84] Election turnout for union leadership spiked during this period, and, as an indicator of rank-and-file participation, this suggests that the ILWU democracy was particularly strong during the period of the 1948 strike.

A second measure of organizational culture is the importance placed on inclusion and fairness, as was seen in the battle for the hiring hall. The resistance to the open shop was caused by a fear of returning to the old hiring systems, under which those workers favored by the employers got as much work as they wanted, while others were left wanting. A hiring hall meant an end to bribery, favoritism and arbitrary hiring through the introduction of job rotation and wage equalization. All workers were “dispatched from one hall and everything had to be worked fairly and squarely.”[85]

Another feature of the organizational culture found in the ILWU’s participatory democracy was that the membership was able to overpower the leadership and direct policy if it chose to do so. This is what happened during World War II, when Bridges had followed the Communist Party’s policy of labor sacrifice and increased productivity in order to aid the war effort. The membership, unwilling to be completely accommodating, effectively changed the union’s policy. Productivity did not increase and in some cases decreased.[86] The reaction represented that, in the words of sociologist Howard Kimeldorf, “the workers, not the union or Bridges, ‘owned’ their jobs, and they were the ones who, torn by the conflicting loyalties of nationalism and class, ultimately determined the proper mix of accommodation and resistance on the docks during the war.”[87]

The final component of an organizational culture is communication of information to the membership. One obvious method used throughout the 1948 strike was The Dispatcher, created in 1942, and the strike bulletins published to keep workers informed.[88] Additionally, the ILWU had won the right in 1934 to hold ‘stop work’ meetings, which facilitated the sharing of ideas and information amongst members.[89] These regular meetings were important because all workers were given time off to attend, to ensure that all who wished to speak their mind could do so. During the 1948 strike, these meetings allowed for things such as organizing pickets, discussing agreements, and encouraging solidarity.[90]

The ILWU’s strong, participatory democracy as it existed in 1948 helps to explain why the attacks on Bridges and the leadership by the WEA were unsuccessful, despite growing divisions within the union. Rather than being seen as attacks on the political belief of the leaderships, the WEA rhetoric was perceived as an attack on union autonomy, and united members in a defense of the union’s democracy and its right to determine its own internal affairs. Employers needed to alienate the leadership of the ILWU from the rank-and-file membership if they were going to be successful in bringing about a change of command. To do this, they ran a publicity campaign portraying Bridges as a dictator who shamelessly exploited the rank-and-file membership in order to operate the union according to the Communist Party line. For example, the WEA’s publicity office encouraged ILWU wives and families to write letters to the press recounting the hardships the strike was causing and urging the union to comply with Taft-Hartley and the employers’ demands.[91] One letter to the editor of the Portland Daily Journal from a longshoreman’s wife did just this, stating that workers’ wives do not like Bridges, and neither did most of their husbands, but that they kept quiet for fear of being beaten up.[92] Since the letter is anonymous, there is no way to verify the author as a union member’s wife, but regardless of authenticity it demonstrates the discourse designed to convince members that Bridges and the leadership did not have their best interests at heart. In a letter accompanying a white paper sent out to longshoremen, Foisie writes,

We want to do business with you and a leadership that truly represents your interests and the interests of the public at large. Our records and your records show that for 14 years the main concern of your present leadership has been primarily a political interest that closely follows the Communist Party line. Your long-range welfare has been considered of secondary importance.[93]

This 1950 newsreel clip shows Harry Bridges following his perjury conviction for denying that he had been a member of the Communist Party. He replies to reporters' questions showing the wit and radical idealism for which he was famous. (1 minute) Click to play

The words sound strikingly similar to the critiques made of Bridges by union members during World War II, when Bridges wanted to follow the Communist Party’s policy of accommodation, the membership guarded against giving up so easily it’s hard fought gains for the sake of the war effort. [94] Playing up these existing divisions between rank-and-file members and the leadership was important because, as a democratic union, the only way to get rid of Bridges was for the membership to vote him out.

The membership, however, held a deep affection for Bridges. Despite being to the left of the membership, he was able to maintain his position for over four decades.[95] Much of this loyalty comes from his leadership during the 1934 strike and his role in the foundation of the union; Bridges became the union’s hero and came to symbolize the ILWU itself.[96] On a more pragmatic level, the loyalty to Bridges was the result of his ability to deliver gains from employers. While Howard Kimeldorf suggests that this success was a result of the militancy of the ILWU membership rather than Bridges’ ability alone, the prosperity of the union under his leadership certainly added to his popularity. While the rank-and-file members often disagreed with Bridges, his success as a negotiator and role as a symbol of the ILWU helped him maintain popularity. As a Seattle banker stated, “He’s the most radical labor leader in the country. Yet those longshoremen would follow him into a fiery furnace.”[97] Despite the growing political conservatism of the Cold War, the union was able to distance Bridges from his leftist politics because his popularity was derived not from shared political philosophies but instead from a deeply ingrained loyalty to their president. Attacks on Bridges were ultimately unsuccessful as they were interpreted as an attack on the union itself, which rallied the membership to Bridges’ defense.[98]

The attempts to get rid of Bridges were not new, but in 1948 the attacks could no longer simply be ignored as red-baiting since the continuation of negotiations seemed to require a change in leadership. By demanding that a “responsible leadership” be installed instead of the one the union members had deemed fit, the attacks shifted from being about Bridges to being about union autonomy. As one strike bulletin stated, “we decide union policies…not the ship owners.”[99] The right to choose who represented the union was especially important with the revival of the argument over the hiring hall. Fears of a return to the open shop systems seen before the 1934 strike were fresh in the workers’ minds, since the hiring hall was made the primary issue of negotiations from February until September. The unions under the fink hall and shapeup were weak, ineffective, and had a leadership of company-favored men.[100] This fear of return to the pre-1934 company unions is evident in the language used in an advertisement saying, “Our officials are elected by secret ballot from the ranks- they are persecuted because they refuse to sell out.”[101]

The ILWU took great pride in their democracy, and the WEA’s attacks therefore threatened something they held dear. In a response to a report from the employers, the union explained, “If they are not satisfied with the way things are going between themselves and the union, they will have to change the membership not the leadership. After all, the union is not controlled by a board of directors sitting in an ivory tower.”[102] This quote represents the strong faith that the ILWU’s democracy produced leaders who were completely reflective of the membership’s wishes. Radio programs and fliers touted the level of democracy in the ranks of the union, as did the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), who stated that it was one of the most democratic unions in the country.[103] This faith in the democracy of the union enabled the union to maintain a high level of solidarity through the strike; even though there were people who disliked Bridges, they accepted him because he was elected through a legitimate and respected process.

Looking forward: 1950 and beyond

As relations between the ILWU and the employers were finally reaching a period of cooperation, the union found a new conflict from within the American labor movement. The ILWU’s support of Wallace rather than Truman and their lack of support for the Marshall Plan caused problems with the CIO, which insisted on conformity of its member unions to the organization’s more conservative national policies.[104] This tension had existed during the 1948 strike, when it took until late October for Murray and the CIO to come out in support of the ILWU.[105] The CIO, following its post-war path of growing conservatism, purged the left-led unions, such as the United Electrical Workers, the Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers, the NUMCS, and the ILWU, from within their ranks. Although there were trials, the outcome was a foregone conclusion.[106] In 1950, the ILWU was kicked out of the CIO. Of the eleven unions purged, only the ILWU was able to maintain its strength; the others were raided by rival unions and many were dissolved.[107]

As the United States entered a period of prosperity in the 1950s, the American labor movement seemed content. An era of labor peace was born out of this prosperity, as the growth in wealth satisfied workers and many became part of a rising middle class.[108] This decline in militancy, caused by complacency and the purges of the radical left, characterized American labor unions for decades to come. This raises the issue of ILWU exceptionalism. Many scholars have identified the ILWU as an outlier in the history of American labor. The 1948 strike and its aftermath support this conclusion. However, it is important to first recognize the ways in which the union was not exceptional. Like other unions in the post-war period, the union’s leadership was fairly static.[109] Bridges remained in power for 43 years, until his retirement in 1977.[110] More importantly, after the 1948 strike it would be another 23 years before the longshoremen carried out another major strike. The system for arbitration set forth under the 1948 agreement bureaucratized industrial relations and led to industry-wide peace. These same forces also caused deradicalization in the CIO. However, its survival outside of the CIO and resistance to anticommunist pressures indicates that something differentiated the ILWU from the rest of American labor.

To complicate the issue, while the ILWU’s strong participatory democracy separates it from the majority of unions in both the AFL and CIO, many of the purged left-wing unions were also characterized by strong democracies.[111] If a strong democracy is a characteristic that helps explain the ILWU’s survival, why were these other democratic unions unable to do so as well? To explore this a bit further, the National Union of Marine Cooks & Stewards (NUMCS) provides a convenient comparison because like the ILWU was a highly democratic, left-wing CIO maritime union, but unlike the ILWU, it did not survive the Cold War. It was described by employers as the ILWU’s satellite during the 1948 strike, and the NUMCS membership held their left-wing president Hugh Bryson in high regard.[112] After expulsion from the CIO, the union’s affiliation was fought over by the SUP, and the NUMCS’s large minority membership criticized it for racism. Dissension grew regarding leftist politics within the NUMCS, and the AFL-affiliated SUP gaining control of the union.[113] In a 1955 NLRB vote the membership voted 3,931-1,064 to affiliate with Seafarers International Union (SIU), the parent organization of the SUP, won instead of the ILWU.[114]

So what does the case of the NUMCS tell us? While the SUP used electoral tactics to edge the vote in their favor, the takeover was ultimately made possible because an internal shift in politics had taken place within the NUMCS, enabling the formerly leftist organization to be taken over by conservatives. It was not so much a failure of the NUMCS democracy, but a reflection of a membership whose views reflected the growing conservatism of the Cold War. The ILWU, on the other hand, was able to resist these pressures, maintaining their rank-and-file culture of democracy and radicalism.

It would appear that the mere presence of a democracy was not sufficient for survival. The ILWU democracy was not just a system of union governance however; it was rooted in and epitomized a larger workplace culture rooted in solidarity and union militancy. While it is true that the longshore division of the ILWU experienced a labor peace after 1948, this period of cooperation with employers did not result in a decline in radical unionism. Instead, the militancy of the ILWU led it to continue to organize new members and diversify its membership. For example, during the 1940s and 50s, it worked to organize Hawaiian sugar and pineapple plantation workers, prevailing over ethnic divisions and enabling political empowerment, enthusiasm for democracy and unionization among workers.[115] The ILWU also grew through its acceptance of new, diversified workers into its ranks, such as fishermen and cannery workers.[116] This resiliency was also demonstrated when the Tacoma ILA local finally joined the ILWU in 1957.[117] Organizing strengthened and spread the organizational culture of the ILWU. Although the longshore division remained the strongest, the act of spreading a participatory culture to new industries reinforced the ideals of the union. This continued militancy and reinforcement of workplace culture and democracy enabled the ILWU to survive where other democratic leftist unions failed.

. Although it would be another 23 years before the ILWU would have another major strike, it was able to maintain high level of membership participation, as evidenced by the consistently high voter turnout rates in both national and union elections.[118] The ILWU is a clear example of the importance of a participatory democracy in maintaining a strong, progressive union.

©Ashley Lindsey, 2013

[1] Statement from Employers, Local 10 Timeline in Seattle Area Local 19 Bulletins, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[2]“Warehouse Settled, Waterfront Still Uncertain,” The Dispatcher, June 13, 1947.

[3] Publicity- Employers, Coast Strike Period Sept. 2- Dec. 3, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[4] WEA Public Relations Department, Coast Strike Period Sept. 2- Dec. 3, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[5] Memo to Bridges from Lincoln Farley, Research Department Prep For June 15, Coast Committee Box 20, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[6] “Sea Unions Invited To Send Delegates to Action Parley,” The Dispatcher, April 2, 1948.

[7] Chronological Negotiations Feb-Aug, August 18, 1948, Seattle Area Local 19 Bulletins, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[8] Ibid.

[9] WEA Makes Position Clear on Hiring Hall, Issue is Between ILWU and T-H Law Pacific Coast Maritime Report April 12, 1948, Pacific Coast Maritime Report, Vol. 2, no. 5, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[10] Local 10 Timeline, Dec 7, 1948, Seattle Area Local 19 Bulletins, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[11]Strike Ballot, May 20, 1948, Coast Committee Box 20, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[12]Chronological Negotiations Feb-Aug, August 18, 1948, Seattle Area Local 19 Bulletins, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA; Charles P. Larrowe, Harry Bridges: The Rise and Fall of Radical Labor in the United States (Westport, Connecticut: Lawrence Hill & Co., 1972), 294.

[13] Chronological Negotiations Feb-Aug, August 18, 1948, Seattle Area Local 19 Bulletins, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[14] ILWU Local 19 Minutes, Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-001, Box 4, Folders 13-21, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[15] Brobeck, Phleger & Harrison, Statement of Waterfront Employers Association.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Slogans, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Chronological Negotiations Feb-Aug, August 18, 1948, Seattle Area Local 19 Bulletins, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[20] ILWU Local 19 Minutes, Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-001, Box 4, Folders 13-21, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[21] Waterfront Employers of Washington, Correspondence and Minutes, Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-002, Box 10, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[22] Schneider and Siegel, Industrial Relations, 68.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Larrowe, Harry Bridges, 294

[25] WEA Shoreside Report, Vol. 1, No. 10, August 11, 1948, Publicity Employers Coast Strike Period Sep. 2- Dec. 3, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[26] Larrowe, Harry Bridges, 294.

[27] WEA Public Relations Department News Release, August 11, 1948, Publicity- Employers, Coast Committee Box 22, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[28] Employers’ Last Offer Brochure, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[29] ILWU Local 19 Minutes, April 22 1948, Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-001, Box 4, Folders 13-21, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[30] Larrowe, Harry Bridges, 294.

[31] “Taft Hartley Fraud,” The Dispatcher, August 20, 1948; “No Suckers,” The Dispatcher, September 3, 1948.

[32] Referendum on Ship Owners’ Proposals, September 3-14, 1948, ILWU Strike Ballots, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[33] Charles Regal, “Seattle Port Feels Full Strike Effect,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, September 3, 1948.

[34] “Strike Violence- Sailors Fight Longshoremen on Calif. Pier,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, September 4, 1948.

[35] Ibid.

[36] WEA Shoreside Report, August 10, 1948, Publicity Employers Coast Strike Period Sep. 2- Dec. 3, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[37] ILWU Local 19 Minutes, September 13, 1948, Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-001, Box 4, Folders 13-21, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.; “Army May Use Docks in Tacoma,” Tacoma News Tribune, September 10, 1948.

[38] Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[39] “Army Shifts Longshore Hiring Site,” Los Angeles Times, September 18, 1948.

[40] Schneider and Siegel, Industrial Relations, 70-71.

[41] “Richmond Strike Riot is Without Excuse,” Los Angeles Times, September 16, 1948.

[42] “Harbor Strike Stalemated in Fourth Week,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1948; “Strikers Will Unload Animal,” Tacoma News Tribune, September 23, 1948.

[43] “Unions Hit Jackpot in Victories,” The Dispatcher, December 10, 1948.

[44] WEA Public Relations Department News Release, September 25, 1948, Publicity- Employers, Coast Committee Box 22, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[45] Publicity-Employers, Strike Period Sep. 2-Dec. 3, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[46] “Which Flag Do We Fly?” September 16, 1948, San Francisco Chronicle, Publicity- Employers, Strike Period Sep. 2-Dec. 3, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[47] Molotov Advertisement, Publicity- Employers, Strike Period Sep. 2-Dec. 3, ILWU Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[48] Beverly J. Silver, Forces of Labor: Workers Movements and Globalization Since 1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 13.

[49] PASA Public Relations Department News Release, September 28, 1948, Publicity- Employers, Coast Committee Box 22, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[50] “How Would You Like It…” Flier, Publicity-Employers, Strike Period Sep. 2-Dec. 3, ILWU Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[51] “This is Our Berlin, Mr. Truman,” September 23, 1948, San Francisco Chronicle, Publicity- Employers, Strike Period Sep. 2-Dec. 3, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[52] “Which Flag Do We Fly,” Northwest Joint Action Committee, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[53] Ray Irvine and Joe Johnson, “A Report on the Activities of the Joint Action Committee of San Francisco in the 1948 West Coast Maritime Strike,” 2.

[54] Radio Program K.O.L. 8:45 pm, 8/16- 11/29 Union Publicity, ILWU Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[55] Public Correspondence, Leaflets, etc., Speakers Bureau Committee, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[56] Irvine and Johnson, “A Report on the Activities of the Joint Action Committee,” 5.

[57] “Shipowners’ Final Offer Spells Drastic Wage Cut,” The Dispatcher, August 20, 1948, pg. 4.

[58] Minutes of Negotiating Committee, November 6, 1948, Coast Negotiations sept 2-Dec 3, Coast Committee Box 24, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[59] “By Their Own Words,” October 29, 1948, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[60] Larrowe, Harry Bridges, 298

[61] Radio Program, 8:45 pm K.O.L., November 12, 1948, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[62] Minutes of Negotiating Committee, November 6, 1948, Coast Negotiations sept 2-Dec 3, Coast Committee Box 24, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[63] Minutes of Longshore and Shipclerks Negotiations Committee, November 11, 1948, Coast Negotiations Sept 2-Dec 3, Coast Committee Box 24, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA; Return to Work Agreement, November 26, 1948, Coast Negotiations Sept 2-Dec 3, Coast Committee Box 24, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[64] Return to Work Agreement, November 26, 1948, Coast Negotiations Sept 2-Dec 3, Coast Committee Box 24, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[65] Timeline, ILWU Case Briefs, Correspondence, Publicity etc., Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[66] “Winches Are Turning Again along West Coast Piers: What Unions Gained from their Long Strike,” People’s World, December 6, 1948.

[67] Return to Work Agreement, November 26, 1948, Coast Negotiations Sept 2-Dec 3, Coast Committee Box 24, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[68] “Winches Are Turning Again along West Coast Piers.”

[69] Balloting Agreements, Coast Negotiations Sept 2-Dec 2 1948, Coast Committee Box 24, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[70] Larrowe, Harry Bridges, 296-297.

[71] Schneider and Siegel, Industrial Relations, 70.

[72] Irvine and Johnson, “A Report on the Activities of the Joint Action Committee,” 7.

[73] “Attention Longshoremen!” Molander Advertisement, San Francisco Chronicle, November 10, 1948.

[74] Brobeck, Phleger & Harrison, Statement of Waterfront Employers Association.

[75] Summary of Panel Discussion, WEA & ILWU, March 3, 1949, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[76] Schneider and Siegel, Industrial Relations, 84-85.

[77] Letters from Various Locals: Coast Members Failing to Report for Strike Duty, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[78] Kimeldorf, “WWII and the Deradicalization of Labor,”262.

[79] Margaret Levi et al., “Union Democracy Reexamined,” 207.

[80] Ibid., 212.

[81] Radio Program, 8:45 pm K.O.L., October 25, 1948, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[82] Stepan-Norris, Left Out, 237.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Margaret Levi et al., “Union Democracy Reexamined,” 214.

[85] Frank Jenkins, interview by R.C. Berner, June 6 and 28, 1972, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[86] Kimeldorf, “WWII and the Deradicalization of Labor,” 261.

[87] Ibid., 262.

[88] Margaret Levi et al., “Union Democracy Reexamined,” 211.

[89] ILWU Local 19 Minutes, March 18, 1948, Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-001, Box 4, Folders 13-21, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[90] ILWU Local 19 Minutes, September 2- November 27, 1948, Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-001, Box 4, Folders 13-21, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[91] ILWU Coast Committee Union Publicity: Seattle Area, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[92] Newspaper Clippings, September 30, 1948, Coast Committee Box 22, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[93] Frank Foisie to Longshoremen, letter with white paper, October 12, 1948, Publicity–Employers, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[94] Kimeldorf, “WWII and the Deradicalization of Labor,” 261.

[95] Margaret Levi et al., “Union Democracy Reexamined,” 214.

[96] Kimeldorf, Reds & Rackets, 164-165.

[97] Ibid., 7.

[98] Ibid., 164.

[99] Local 10 Strike Bulletins, September 7, 1948, Coast Committee Box, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[100] Markholt, Maritime Solidarity, 20, 30-31; Schneider and Siegel, Industrial Relations, 8.

[101]“We Protest the Witch Hunt”, Union Publicity San Francisco Bay Area, Coast Committee Box 22, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[102] “ILWU Answers Latest ‘Short Sighted Report,” Union Publicity Seattle Area, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[103] Radio Program, 8:45 pm K.O.L., October 25, 1948, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA; NAACP Press Release, September 15, 1948, Public Correspondence, Coast Committee Box 24, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[104] Lawrence Lader, Power on the Left : American Radical Movements Since 1946 (New York: Norton, 1979), 56-66.

[105] “Murray Denounces Shipowners: CIO’s Full Weight Thrown Behind Maritime Strike,” The Dispatcher, October 29, 1948.

[106] Zieger, The CIO, 289.

[107] Lader, Power on the Left, 65.

[108] Fantasia and Voss, Hard Work, 56-57.

[109] Ibid., 87-92.

[110] Margaret Levi et al., “Union Democracy Reexamined,” 214.

[111] Stepan-Norris and Zeitlin, Left Out, 89, table 3.3.

[112] Frank P. Foisie, “The Strike on the Pacific Coast,” speech to the National Propeller Club, October 14, 1948, Publicity Employers Coast Strike Period Sep. 2-Dec. 3, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA; Kimeldorf, Reds and Rackets, 168.

[113] Jane Cassels Record, “The Rise and Fall of a Maritime Union,” Industrial & Labor Relations Review 10, no. 1 (October 1956), 87.

[114] Ibid., 90.

[115] Schwartz, Solidarity Stories, 244, 273

[116] Preliminary Guide to the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union Fishermen and Allied Workers Division, Local 3 Records, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA; Preliminary Guide to the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union Local 7 Records, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[117] “AFL or CIO: Why did the Tacoma longshoremen choose to remain outside the ILWU for Twenty Years,” Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-002, Box 10, Folder 36, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[118] Margaret Levi et al., “Union Democracy Reexamined,” 214-216.