This prize-winning report is presented in two parts:

Part 1: The confrontation takes shape (this page)

Part 2: Ninety-five days to victory

Ashley Lindsey's article won the 2013 Library Research Award given by University of Washington Libraries and the Best Paper Award given by the UW Department of History

by Ashley Lindsey

We’ll show you that the membership, not the officials, are the boss. They should be. Because they are the unions.

-Maritime unions’ radio program, October 25, 1948.

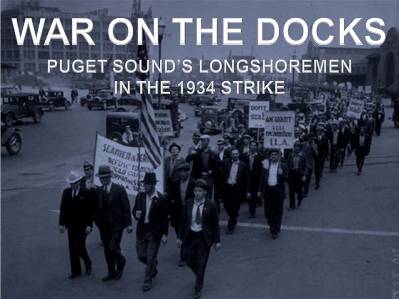

For all of its reputation as a militant progressive union, the ILWU has been very cautious about strikes. Founded in the great maritime strike of 1934, the longshore union struck again in 1936 and then only twice more in 1948 and 1971 plus the lockout of 2002. All of these struggles have been highly consequential. None more so than the ninety-five-day strike of 1948 that tied up West Coast ports from San Diego to Alaska.

Waged in the context of the escalating Red Scare and shortly after the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act which the ILWU had actively defied, the 1948 conflict should have destroyed the leftwing union with its much publicized communist-linked leadership. Certainly that is what the Waterfront Employers Association (WEA) expected when it all but refused to negotiate with Harry Bridges and the ILWU bargaining team. Instead the 1948 shrike became a defining victory that secured the future for the ILWU, insuring that it would survive the Cold War anti-labor persecutions that destroyed most leftwing unions.

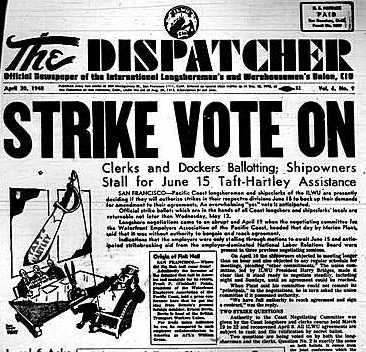

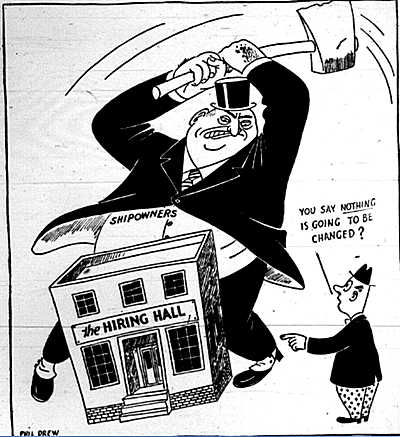

It was an awkward time for a strike. The anti-labor Taft-Hartley Act had become law in June 1947. It outlawed the closed shop and required union officials to sign affidavits swearing that they were not supporters of the Communist Party. Employers thought that the new law gave them the upper hand. The Waterfront Employers Association, led by Frank P. Foise, wanted to dismantle the hiring hall which had been won by the union in 1934 and which was regarded as key to worker solidarity. Employers also hoped to force the union to get rid of leftwing leaders. Antagonism between the ILWU and the WEA was nothing new, but in 1948 it had reached new heights.

Clark Kerr had the unhappy task of trying to mediate in the months before the walkout. He recalled one session where he had asked WEA President Frank Foise to meet one on one with ILWU President Harry Bridges. Foise led off:

Mr. Bridges, we do not know what you are going to demand, but, by God, the answer is no. ” Bridges replied: ‘To tell you the truth, Mr. Foisie, we have not yet finally decided on our demands, but, by God, we will never take no for an answer. ” So the parties turned to me and told me that here was my case, that they had negotiated. [1]

Unable to reach an agreement on the issues of hiring and the politics of the union leadership, the longshoremen and a coalition of other marine unions walked out on September 2, 1948. The strike shut down the United States’ West Coast ports, effectively bringing trade and commerce to a standstill. The strike lasted more than three months during which union members displayed an intensity of purpose and level of solidarity that defied the expectations of employers and many observers. Ultimately it was the employers who gave up. For the ILWU it was not just a short-term victory. Out of the strike came a complete reversal of the nature of waterfront labor relations. In place of open hostility, employers instituted a policy of mutual cooperation with the ILWU, known as the “new look, ushering in an era of peace on the waterfront. [2]

.jpg)

The Dispatcher, March 19, 1948, p2.

The recently enacted Taft-Hartley Act emboldened the Waterfront Employers Association and left the union vulnerable to federal intervention.

The events of 1948 raise several questions: Why was there such animosity between the WEA and the ILWU? What made the 1948 strike so difficult to settle? What led to the complete reversal in the two parties’ attitudes from hostility to cooperation?The answers to these questions can be found in an examination of the national political climate of 1948, as well as the internal politics of both the WEA and the ILWU. Shifts away from New Deal progressivism and towards a new Cold War conservatism had already began to take place by 1948, and these changes challenged the great gains workers had made during the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The WEA believed that the tide had turned enough in its favor to get rid of Bridges and other left-wing leaders of the ILWU with whom it had been bitterly fighting for fourteen years. However, in a period when radical unions across the country came under attack and became increasingly weak, the ILWU resisted and survived, ultimately winning a peace with employers that would last for more than two decades. This change was the result of a severe miscalculation of the political situation by the WEA, both on a national level and within the organizational level. Even after months of attacks by the WEA, the ILWU was able to maintain its solidarity despite facing divisions within its ranks.

This solidarity ensured the union’s strength, forcing employers to back down from their staunch demands to eliminate left-wing radicalism within the ILWU. Why was this possible?In a time when other labor organizations were purging their left-wing leaders, why was the ILWU an exception? The answer lies within the democracy of the ILWU. The union’s history of radical, militant unionism and participatory democracy enabled it to withstand the employers’ attacks during the 1948 West Coast maritime strike. The ILWU became an exception to the many left-wing unions that were dismantled or weakened by anti-communist sentiment.

To uncover how the ILWU was able to survive in the midst of such hostility, an understanding of the union’s past, its identity, its democratic structure, and the impact of World War II and the early Cold War on American politics, labor, and the waterfront industry is necessary. This analysis will reveal the presence of a highly participatory democracy which promoted solidarity, enabling a divided ILWU to remain united and establish a peace with the WEA rather than being forced to purge the union’s radical elements. Despite sharing similarities with the rest of American labor, the ILWU proved an exception from national trends in organized labor during the Cold War.

News coverage of the 1948 strike

Here are selected articles about the strike from the Seattle PI, and the Tacoma, News Tribune. Below that are complete editions of the ILWU Dispatcher. Click to read.

Seattle Post-Intelligencer: |

|

Tacoma News Tribune:

|

|

ILWU Dispatcher

Here are complete issues of the bi-monthly Dispatcher from

October 1947 - December 1948

|

The most comprehensive account of the strike exists in Industrial Relations in the Pacific Coast Longshore Industry, by Betty V. H. Schneider and Abraham Siegel, as part of a series on West Coast collective bargaining systems. It presents a history of the hostile relations between the WEA and the ILWU, an overview of the strike, and a brief explanation of the peace reached at the end of 1948. The account does not thoroughly explore the social and political history of the union, instead primarily focusing on the economic causes and impacts of the strike. This paper delves into that history to develop a better understanding of the strike both inside and outside the negotiating room. Because Schneider and Siegel’s book was published in 1956, less than a decade after the strike ended, a fresh look at what the strike and the “new look” meant to the longshore industry is necessary as well. Much has been written about communism and radical labor within the United States, particularly about its downfall after World War II. Enough time has passed to begin placing the strike within this conversation; by offering an exception to the story of de-radicalization and growing conservatism, the 1948 West Coast maritime strike offers insight into why the rest of American labor was so susceptible to the pressures of the Cold War whereas the ILWU was able to resist. While not as comprehensive as the book by Schneider and Siegal, another account of the 1948 strike is included in Charles Larrowe’s Harry Bridges: The Rise and Fall of Radical Labor (1972). The biography largely focuses around the political attacks made against Bridges rather than the strike’s importance to the union as a whole, but still offers insight into the relationships between the ILWU and WEA leadership. Additionally, the ILWU and employers’ web sites both contain information about the strike, highlighting the importance of the events of 1948 to the development of relations on the West Coast Waterfront.

It is important to note the sources used to piece together the story of the strike. Many of the sources came from the ILWU archives at the Anne Rand Memorial Library, while others came from the Labor Archives of Washington at the University of Washington. Generally, sources for the ILWU were more plentiful than those from the WEA, as great care has been taken to preserve the history of the American labor movement. Additionally, most sources reflect the opinions of the leadership of both organizations, rather than the membership or general public, as most of the paper trail left from the 1948 strike was from the organizers and leaders within the ILWU and WEA. Voting records, letters, and some meeting minutes are a few sources that offer insight into the rank-and-file opinions during the strike. It is my hope that this paper, by attempting to use sources from both sides, as well as from various levels of authority, will more fully develop the story of the 1948 strike.

Organizational Culture of the ILWU

Relations between the WEA and the ILWU in 1948 can only be understood with background knowledge of how waterfront workers came to be organized on the West Coast, particularly in regards how the ILWU’s strong culture of solidarity and democracy developed, the importance of the hiring halls to the union, and the significance of the 1934 in creating the ILWU’s identity. An understanding of the past enriches the story of the 1948 strike; it explains the animosity between the WEA and the ILWU, as well as contextualizes the attacks made by the employers and the union’s response.

The organizational culture of the ILWU was central to the union’s success in rebuking attacks made by employers during the strike. An organizational culture can best be defined as the way a group of people choose to organize themselves, the ways members relate to one another, and why. The ILWU’s organizational culture therefore can be defined as a participatory democracy influenced by, among other factors, the radical tendencies of the workers who came to be employed on the waterfront and the nature of longshore work. The predominantly male longshore population came largely from the logging and various maritime industries emerging in the western United States, which attracted a demographic on the fringes of society who often held radical political tendencies.[3] These workers often took work as longshoremen, and occupational communities formed along the waterfront, facilitating the sharing of new, radical political ideas.[4] Many of these workers were European immigrants from Scandinavia and Germany, populations which tended to be more socialist and radical than the American population at-large.[5] Syndicalism and the Industrial Workers of the World, or Wobblies, became prevalent on the waterfront.[6]

Another key component of the ILWU’s organizational culture is an emphasis on solidarity. In part, this derives from the philosophies of the left, encouraging an encompassing sense of social responsibility, which is evident in the ILWU’s slogan, “An Injury to One is an Injury to All. ” which had been a slogan of the Knights of Labor and the IWW[7] Longshore work was physically hard and dangerous, so workers needed to be able to rely on their coworkers for their own safety.[8] Working in groups known as gangs, longshore work reinforced bonds that already existed amongst the working communities that formed around the waterfront.[9] The fellowship formed through the sharing of dangerous, hard work would be another element of the workplace culture that would lay the foundations for the solidarity which enabled the ILWU’s success in 1948.

Another element of the ILWU’s past that would be critical in the 1948 strike was the experiences of workers under past hiring systems. The union-controlled hiring hall system in place since the foundation of the ILWU came under attack during the strike because employers believed its closed shop was illegal under the recently passed Taft-Hartley Act. Negotiations came to a standstill as the ILWU was unwilling to surrender the hiring hall, which was an integral part of the union and its identity. Prior to the 1930s, because there was no uniform system of organization of workers or employers, hiring systems varied from port to port. Although unionization had existed on the West Coast longshore industry before the ILWU under the International Longshore Association and the Riggers and Stevedores’ Union, several unsuccessful strikes and factionalism rendered both unions ineffectual.[10] The systems in place in Seattle under the “fink hall,” the “shape up” in San Francisco, and the hiring hall system in Tacoma, reveal the importance corrupt open shop hiring systems played in shaping the identity of the ILWU.

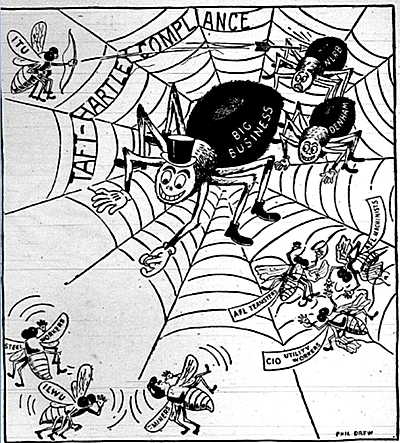

This cartoon from the April 16, 1948 Dispatcher sounded the alarm as the Waterfront Employers Association signaled that they wanted to end union-controlled hiring halls.

The open shop hiring system known as the “fink hall” originated in Seattle, under the leadership of Frank P. Foisie, but eventually spread to other ports, including San Pedro and Portland.[11] Essentially an employer operated hiring hall, the system allowed employers to decide who got work and how much. A known union supporter might be blacklisted and unable to get a job.[12] Not only did the system hinder union organizing, but it also encouraged corruption, and workers would often pay bribes in order to get work.[13] There was no rotation system amongst workers, so favored workers could be given job after job while others would have to wait days or weeks without employment.[14] The arbitrary nature of the fink hall meant that not only were longshore workers doing a dangerous, physically hard job, but they had little to no job security.

San Francisco’s shape up, where workers would gather on the docks in the morning and gang bosses would choose who got work from the crowd, was slightly different than the fink hall, but had many of the same problems. As in the fink hall, bribery was commonplace, and those who refused or could not pay to gain favoritism often found themselves waiting on the docks all day in hope of a job vacancy.[15] The systems of hiring on the waterfront like the fink hall and the shape up made longshoring a tenuous livelihood, and would come to symbolize the blatant corruption and disregard for workers’ well being that existed before the 1934 strike and the formation of the ILWU. These past experiences with employer-controlled hiring would color the ILWU’s reaction to the WEA’s attacks on union-controlled hiring during the 1948 strike.

The case of the International Longshore Association (ILA) local in Tacoma serves to highlight the importance that eliminating these open shop hiring systems had on the formation of the ILWU and its culture. Unlike most West Coast ports, before the 1934 strike the Tacoma local of the ILA had a system of union-controlled dispatching through a hiring hall, which meant the union enjoyed a greater degree of job security because workers were not forced to gratify the bosses in order to gain employment.[16] In 1937, the Tacoma local was one of a number of locals to remain with the ILA, affiliated with the more conservative American Federation of Labor (AFL), rather than switch to the newly formed ILWU that was affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). This conservatism can in part be explained by lacking an experience with either the shape up or the fink hall; because Tacoma was already satisfied with its union and hiring hall system, the desire to install a new system was minimal. This suggests that in places like Seattle or San Francisco, the new brand of industrial, militant unionism that arose with the ILWU can, in part, be explained by their experiences with the open shop hiring practices that were so detrimental to workers.

See our special section on 1934: The Great Strike which includes a short film by Ron Magden, a powerpoint slide show by Steve Beda, detailed day-by-day report by Rod Palmquist, complete database of news coverage by Rachel Byarley, a photo archive, and fully digitized collection of the Waterfront Worker.

The frustration with working conditions and employer treatment came to a head in the 1934 Strike. The West Coast ILA locals went on strike on May 9 and were soon joined by other maritime workers.[17] Violence occurred all along the coast, and on July 5, after an intensification of the conflict days earlier, two strikers were shot and killed in San Francisco.[18] This would become known as Bloody Thursday, and helped rally the public to the cause of the strikers.[19] Eventually the union was able to gain major concessions from employers. In terms of the 1948 strike, 1934 was important because it secured the first coastwise contract, giving new strength to the bargaining power of the union. Secondly, it created the union controlled hiring hall, which would give workers control over jobs and ensure equality and fairness in the distribution of work. [20] Lastly, because it was such a hard fought victory, it served as a sort of “foundation myth” for the ILWU and therefore played a significant role in the formation of the militant workplace culture and pride in the ILWU identity. A few years later in 1937, the ILWU was formed as the vast majority of West Coast longshore locals left the AFL’s ILA to join the newly formed CIO, which focused more on social justice and better fit the ILWU’s radical tendencies.[21]

A Union Divided

During World War II, divisions arose within the ILWU. Tactics used by the WEA during the 1948 strike would attempt to manipulate these divisions, which would seemingly weaken the union’s solidarity. The employers’ decision to aggressively attack the radical leadership of the ILWU can be traced to this perceived weakness arising from changes that occurred during the war.[22] With the outbreak of World War II, ports along the West Coast faced a new pressure to increase production for the sake of the war effort. The skyrocketing demand for manpower and need for stability had a powerful impact on the ILWU. Political arguments within the union and fundamental changes in the demographics of the membership would eventually lead to divisions which created differences both between rank-and-file members and between members and their leadership.

First, such divisions were in part caused by a desire for stability and efficiency to better serve the war effort. Stability, critical to a nation at war, required cooperation between employers and workers that did not exist in the West Coast longshore industry. The ILWU’s leadership urged a conciliatory approach to work and relations with employers in order to support the war effort. This was in line with wartime practices in most AFL and CIO unions and also accorded with Communist Party policies. According to Fantasia and Voss, the war-era accommodations served to “dampen the militancy of American workers and solidarism of industrial unionism,” through policies like participating with management on war boards and the prohibition of strikes.[23] In the ILWU, the “Bridges Plan,” named for Harry Bridges, created a council that brought the union, employers and the government together in order to ensure security and efficiency for military cargo.[24] In giving a stronger voice to employers and the government, the plan signified that the union was willing to alter its staunch radicalism and relinquish certain elements of autonomy to support the war effort. In addition to agreeing to the Bridges Plan, the ILWU also signed a no-strike pledge, which largely prevented work stoppages that created insecurity and inefficiencies in the ports.[25]

These efforts represented a shift, at least at the level of the union’s leadership, away from radicalism and towards a tamer, more bureaucratic union. While patriotism and support for the war was nearly unanimous within the union, not all members agreed with the extent to which the union was sacrificing militancy in support of the war.[26] Although Bridges and the leadership had enough support for their policies to be adopted, they were met with resistance by workers who had all too recently fought a violent struggle to gain the benefits of unionization. For example, the Bridges Plan took three months to get endorsed by some locals in the Pacific Northwest with stronger left-wing traditions.[27] Bridges was booed and laughed at by members at one meeting where he described his wartime plan, and was told, “Just because your pal Joe Stalin is in trouble, don’t expect us to give up our conditions to help him out. ”[28]

Demographic changes also reshaped the union during the war. With ports busier than ever, thousands of new dockworkers were needed to keep the ships moving. The increased demand was coupled with the exodus of some ILWU veterans who left for military service or different jobs, some leaving because of disagreement with Bridges' policies.[29] Initially, new members were found though the “brother-in-law” system, where workers could sponsor family members and get them jobs.[30] This system allowed for the make-up of the union to remain fairly constant, as relatives tended to have similar political, cultural and racial backgrounds. However, the demand for labor was higher than the brother-in-law system could fill. Soon, new workers were flooding to the docks in search of work. In San Francisco, the number of workers doubled between 1938 and 1945, and in Seattle, the last three years of the war saw the labor force more than triple.[31]

This influx changed the racial demographics of the union. The number of workers of color increased significantly. In the early days of the union, the membership was fairly homogeneously white.[32] As new workers were drawn to the waterfront from across the nation, an increasing number of black and Mexican-American workers came to join the union. More than one in five of the new workers were either black or Mexican-American and by the time the war drew to a close, nearly a third of members of Local 10 in San Francisco, California were black.[33] At the same time, there was an influx of rural whites, disparaged as “rednecks” or “Okies” by the veterans, many of whom were politically conservative and openly racist.[34] While the leadership of the ILWU took a strong stance for racial equality within the union, some rank-and-file members resisted integration. Locals adopted racial equality to different extents; whereas San Francisco was more accepting, locals in Portland and San Pedro were segregated.[35] Existing racism was exacerbated when minorities began joining the workforce in greater numbers during the war, even leading to work stoppages and slowdowns.[36] As one longshoreman recalled the reaction of the longshore workers to their new co-workers, “old-timers wouldn’t work with a black guy. [They] would turn around and call a replacement. ”[37] The prominence of the race issue during World War II led to divisions within the union, both between the membership on account of race, and between the leadership and racist members of the union.

Generational differences also divided the workers. [38] Among those who had experienced 1934 together, there was a sense that their sacrifice merited a measure of respect from the other workers. Not only did the generational gap lead to a feeling of superiority among the veteran members, but differences in experience also led to political divisions between generations. Newer members who had not lived under the conditions before the union and had never experienced a major strike lacked the same left-wing radicalism of the older generations of workers. This was particularly true among the growing number of conservative rural whites who joined during the war.[39] In response to a letter from a longshoreman’s wife critical of Bridges and the union during the 1948 strike, another longshoreman’s wife calls her “Mrs. Johnny-come-lately,” and accuses her of not knowing, “what it was like in the ‘good old days’ before the hiring hall, when your man had to lick the employer’s boot to work. ” This letter demonstrates deep generational divisions, as she dismisses the woman’s critical opinion as being solely the result of her and her husband’s inexperience in the union, even though there was no evidence in the original letter suggesting as much.[40]

Racial, generational and political divisions often mutually constituted. Many of those who held negative opinions of racial minorities also disliked those members with left-leaning politics, evident when one such worker in Portland declared, “when the local voted to keep out the ‘niggers’ they should have voted to kick out the ‘commies’ also. ”[41]As a result, many black workers became affiliated with the political left where they found acceptance. Because many of the minority workers were new to the union, a generational bias was often combined with racial discrimination. This intersection of biases is evident in the words of one longshoreman, who said, “I’ll tell you, back in ’33 and ’34…I pounded the bricks for this union, when you all were still back in Africa!”[42] Because the ILWU membership shifted during the course of World War II, factionalism arose that would seemingly weaken the union.[43]

Setting the Stage 1947-1948

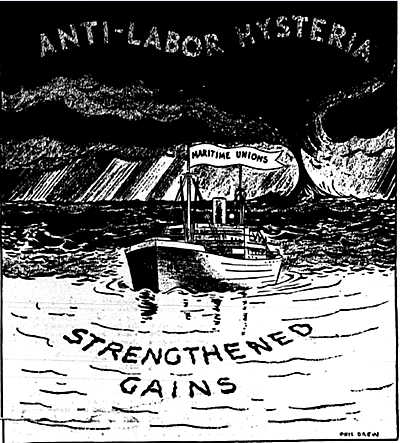

The Dispatcher, February 20, 1948, p1.

As illustrated in these Dispatcher cartoons, the ILWU was keenly aware of the looming threat of the Taft-Hartley Act and the escalating anti-labor and anti-communist rhetoric as contract maneuvers began in early 1948

“Out of the Storm?,” The Dispatcher, June 27, 1947, p2.

“The Spider and the Fly,” The Dispatcher, December 12, 1947, p2.

The 1948 West Coast maritime strike did not happen in a vacuum; rather, changes within the labor movement and a political shift determined an aggressive approach by the WEA against the hiring hall and the radical leadership of the ILWU. The labor movement, particularly the CIO, experienced a deradicalization after World War II. Although a major strike wave had occurred in 1946 following the end of the war, the CIO under the leadership of Phillip Murray was increasingly conservative.[48] Part of this conservatism arose out of the accommodation of the war period. Having instituted grievance machinery, any disagreement was taken through the system rather than protested through a work stoppage or other form of job action.[49] Labor’s wartime cooperation gave unions an institutionalized position in the workplace, securing their existence and decreasing the need to fight employers.[50] The widespread damage caused by World War II in leading foreign economies decreased competition for United States businesses, a new sense of prosperity arose and an increased enjoyment of the “trappings of managerial class” decreased union radicalism.[51]

A political shift had taken place outside labor as well. In November, 1946, the Republican Party had been able to win both the House of Representatives and the Senate.[52] Their Republican-controlled Congress later passed the Taft-Hartley Act, which rolled back many of the gains for labor had made during the Roosevelt administration. The law made it harder to form a union, outlawed the closed shop, allowed states to pass “right to work” legislation that further limited the power of unions, and included a requirement that union leadership sign anti-communist affidavits in order to use the services of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).[53] This would lead to a purging of communist leaders and raids on radical unions, including the ILWU, by their more conservative counterparts. As anti communism swept the nation, labor radicalism became the enemy. With the ILWU facing internal divisions and the industrial labor movement weakened, both through the deradicalization of the CIO and the increasing fear of left-wing politics in the United States, the WEA saw an opportunity to make huge gains when the ILWU contract came up for negotiations.

The status of the longshore industry at the outset of the 1948 reveals some underlying conditions that are important to note during the strike. The longshore industry transitioned back into the hands of private employers after being under government control during the war, but numerous wage increases enacted to draw workers to fill the heightened demand during the war remained in place.[54] Increasing costs, a sharp decrease in trade in the years following the war, and a growth in railroads and trucking inland compelled the WEA to try to make gains during the next bargaining opportunity.[55]

By 1948 the ILWU included other groups like ship clerks, Hawaiian sugar and pineapple workers, and warehouse workers, in addition to longshore workers. [56] ILWU locals were located all along the West Coast in California, Oregon, and Washington, as well as in Hawaii, some southern states, and British Columbia, Canada. [57] While this paper focuses on the longshore division, it is worth noting that the union continued to expand into other industries during this time. The longshore division was made up of somewhere between 11,000 and 26,000 workers, representing workers in nearly every port on the West Coast of the United States. [58] The ILWU had conflicts with other unions, such as the Teamsters, who fought the ILWU for jurisdiction over the warehouse work. [59] More importantly for 1948, another longstanding conflict existed between the Sailors Union of the Pacific (SUP) and their leader Harry Lundeberg, who was often at political odds with Bridges; one worker recalled a saying that “this waterfront isn’t big enough for the two Harrys. ”[60] Lundeberg was conservative, and had worked with Senator Robert Taft, co-author of the Taft-Hartley Act, in order to “keep reds out of the [SUP]. ”[61] The conflict between the trade unionism of the AFL-affiliated SUP and the industrial unionism of the ILWU symbolizes a greater conflict in the labor movement between radicalism and conservatism that would grow during the Cold War.

Part 2: Ninety-five days to victory

©Ashley Lindsey, 2013

[1] Clark Kerr, The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949-1967, vol. 1 Academic Triumphs (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 137.

[2] Jennifer Marie Winter, “30 Years of Collective Bargaining: Joseph Paul St. Sure: Management Labor Negotiator, 1902-1966” (master’s thesis, California State University, Sacramento, 1991),http://www. pmanet. org/?cmd=main. content&id_content=2023238683.

[3] Howard Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets?: The Making of Radical and Conservative Unions on the Waterfront (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 23-24.

[4] Margaret Levi et al. , “Union Democracy Reexamined,” Politics & Society 37, no. 203 (2009): 210-211. http://pas. sagepub. com/content/37/2/203210-211

[5]Seymour Martin Lipset and Gary Marks, It Didn’t Happen Here: Why Socialism Failed in the United States (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001) 137-140.

[6] Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets? 28-29.

[7] Levi et al. , “Union Democracy Reexamined¸” 210.

[8] Harvey Schwartz, Solidarity Stories: An Oral History of the ILWU (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009), 66, 104; Levi et al. , “Union Democracy Reexamined¸” 211.

[9] Levi et al. , “Union Democracy Reexamined¸” 211-212.

[10] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity: Pacific Coast Unionism 1929-1938, (Tacoma: Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1998), 20. ; Schneider and Siegel, Industrial Relations, 8.

[11] Schneider and Siegel, Industrial Relations, 8-9; Markholt, Maritime Solidarity, 26-29.

[12] Schwartz, Solidarity Stories, 104.

[13] Markholt, Maritime Solidarity, 26.

[14] Frank Jenkins, interview by R. C. Berner, June 6 and 28, 1972, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[15] Schneider and Siegel, Industrial Relations, 9.

[16] Markholt, Maritime Solidarity, 26.

[17] Levi et al. , “Union Democracy Reexamined,” 209.

[18] Bruce Nelson, Workers on the Waterfront: Seamen, Longshoremen, and Unionism in the 1930s (Chicago; University of Illinois Press, 1988), 129.

[19] Ibid. ,128.

[20] Margaret Levi et al. , “Union Democracy Reexamined,” 210.

[21] Ibid. , 211.

[22] Article in Journal of Commerce, Union Publicity- San Francisco Bay Area, Coast Committee Box 22, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[23] Rick Fantasia and Kim Voss, Hard Work: Remaking the American Labor Movement (Berkeley; University of California Press, 2004), 46-47.

[24] Howard Kimeldorf, “WWII and the Deradicalization of Labor: The ILWU as a Deviant Case,” Labor History 33, no. 2 (1992): 255. http://dx. doi. org/10. 1080/00236569200890121.

[25] Nancy L. Quam-Wickham, “Who Controls the Hiring Hall? The Struggle for Job Control in the ILWU during World War II,” in American Labor in the Era of World War II, ed. Daniel A. Cornford and Sally M. Miller (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1995), 125.

[26] Quam-Wickham, “Who Controls the Hiring Hall?” 125.

[27] Kimeldorf, “WWII and the Deradicalization of Labor,” 256.

[28] Quam-Wickham, “Who Controls the Hiring Hall?” 126.

[29] Michael Torigan, “National unity on the Waterfront: Communist Politics and the ILWU during

the Second World War,” Labor History 30, no. 3 (2007): 417.

[30] Kimeldorf, “WWII and the Deradicalization of Labor,” 268.

[31] Ibid.

[32] David Wellman, The Union Makes Us Strong: Radical Unionism on the San Francisco Waterfront, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 100.

[33] Kimeldorf, “WWII and the Deradicalization of Labor,” 271; Schwartz, Solidarity Stories, 79.

[34] Kimeldorf, “WWII and the Deradicalization of Labor,” 271; Schwartz, Solidarity Stories, 270.

[35] Judith Stepan-Norris and Maurice Zeitlin, Left Out: Reds and America's Industrial Unions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 237; Jake B. Wilson, “Race, Class, and Gender on the Waterfront: Longshore Workers and the Ports of Southern California” (PhD diss. , University of California, Riverside, 2008), 87-88.

[36] Quam-Wickham, “Who Controls the Hiring Hall?” 133.

[37] Ibid. , 135.

[38] Wellman, The Union Makes Us Strong, 97.

[39] Kimeldorf, “WWII and the Deradicalization of Labor,” 271.

[40]Letter to the Editor, Portland Daily Journal, October 5, 1948, Newspaper Clippings, Coast Committee Box 22, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[41] Kimeldorf, “WWII and the Deradicalization of Labor,” 271.

[42] Quam-Wickham, “Who Controls the Hiring Hall?” , 135.

[43] Schneider and Siegel, Industrial Relations, 8. Factionalism had weakened the ILA locals along the West Coast prior to 1934, making them more susceptible to abuse by employers.

[44] Washington State Industrial Union Council CIO 9th Annual Convention Proceedings, September 26-28, 1947, Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-002, Box 5, Folder 10, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[45] Seattle Area Local 19 Bulletins, Coast Committee Box 21, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA.

[46] Washington State Industrial Union Council CIO 9th Annual Convention Proceedings, September 26-28, 1947, Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-002, Box 5, Folder 10, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[47] Wellman, The Union Makes Us Strong, 10.

[48] Fantasia and Voss, Hard Work, 53-54; Robert H. Zieger, The CIO: 1935-1955 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 212.

[49] Fantasia and Voss, Hard Work, 85.

[50] Ibid. , 47.

[51] Steven Greenhouse, The Big Squeeze: Tough Times for the American Worker (New York; Knopf, 2008), 71; Lawrence Lader, Power on the Left: American Radical Movements Since 1946 (New York:W. W. Norton & Company, 1979), 57.

[52] Zieger, The CIO, 245.

[53] Fantasia and Voss, Hard Work, 53; “Taft-Hartley Law- What’s in it For You?” October 29, 1947, Pacific Coast Maritime Report, Vol. 1, no. 18, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[54] Brobeck, Phleger & Harrison, Waterfront Employers Association of the Pacific Coast and Pacific American Shipowners Association, Statement of Waterfront Employers Association of the Pacific Coast Shipowners Association before Pacific Coast Section, Board of Inquiry, (San Francisco: Parker Print. Co. , 1948).

[55] Schneider and Siegel, Industrial Relations, 45-47.

[56] Schwartz, Solidarity Stories, vi-vii.

[57] “How Locals Voted for Officers, CIO Delegates, andLabor Committee,” The Dispatcher, June 13 1947.

[58] Referendum on Ship Owners’ Proposals, September 3-14, 1948, ILWU Strike Ballots, Coast Committee Box 23, International Longshore and Warehouse Union Archives, Anne Rand Memorial Library, San Francisco, CA; Harry Bridges, “On the Beam,” The Dispatcher, September 3, 1948.

[59] “Teamsters Start Open Raids on ILWU in Two Plants, Aided by T-H Act,” The Dispatcher, Nov 28, 1947.

[60] “Harry Lundeberg: Centennial Tribute 1901-2001,” West Coast Sailors, March 30, 2001,http://www. sailors. org/pdf/newsletter/harrylundebergcentennial. pdf.

[61] “Fearless Lundy in His Undie Uppers Entrances Press and Shipowners,” The Dispatcher, November 14, 1947.