One of the earliest fern books, ”The Ferns of Great Britain” (published in 1855), is better known for its illustrator John Edward Sowerby (1825-1870) rather than the botanist who wrote the text, Charles Johnson (1791-1880). While this was not typical, it is perhaps because Sowerby was also the publisher. There is no record of professional jealousy, as the pair produced several other books on wild flowers, poisonous plants, grasses, and useful plants found in Britain and Ireland.

One of the earliest fern books, ”The Ferns of Great Britain” (published in 1855), is better known for its illustrator John Edward Sowerby (1825-1870) rather than the botanist who wrote the text, Charles Johnson (1791-1880). While this was not typical, it is perhaps because Sowerby was also the publisher. There is no record of professional jealousy, as the pair produced several other books on wild flowers, poisonous plants, grasses, and useful plants found in Britain and Ireland.

The Sowerby family included four generations of noted illustrators from the late 1700s to the early 1900s. For this book, John Edward Sowerby created forty-nine, exquisite copperplate engravings and, in a bit of mid-19th century marketing, sold the finished books in three versions. The images could be left uncolored for 6 shillings, be partially hand-colored for 14 shillings, or fully colored for 27 shillings, a range of about $42 to $189 in US dollars today. The Miller Library copy is partially colored, the best of both worlds as it shows both detail and beauty. Johnson’s text was also outstanding, describing Blechnum boreale (now B. spicant or Struthiopteris spicant), the deer fern as “a highly beautiful fern, well worthy of cultivation as an evergreen little liable to injury by frost, and, during the summer presenting an elegant contrast in its varied fronds.”

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

The Victorian fern craze of the late 19th century was noteworthy for its inclusiveness. All classes of English society were engaged, and participants included men, women, and children. One of the leading botanical authors and illustrators of the time was Anne Pratt (1806-1893) who because of a childhood illness was encouraged to pursue botanical illustration. That she did very well, publishing more than 20 books popularizing botany.

Her ”Ferns of Great Britain” (1st edition 1855, the Miller Library has an undated edition from approximately 1871) was one of her major works and was later combined into a six-volume work that included flowering plants, grasses, and sedges. Her writing shows a clear understanding of the science of her subjects, but she also appreciated the pleasures for the amateur: “It is pleasant to see the rambler in the country searching through green lane or by dripping well for the feather fern.”

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

While the Victorian fern craze of late 19th century Britain had less impact in North America, one noted author who recognized the need for a guide to the ferns of the northeastern United States was Frances Theodora Parsons (1861-1952), who wrote the field guide “How to Know the Ferns” (1899). Parsons was very active in New York City and State politics and active advocate for women’s suffrage. Her autobiography, written late in her long life, talked little of her botanical writing that included three other books. However, during her active botany period, before the death of her second husband in 1902, her books were very popular.

While the Victorian fern craze of late 19th century Britain had less impact in North America, one noted author who recognized the need for a guide to the ferns of the northeastern United States was Frances Theodora Parsons (1861-1952), who wrote the field guide “How to Know the Ferns” (1899). Parsons was very active in New York City and State politics and active advocate for women’s suffrage. Her autobiography, written late in her long life, talked little of her botanical writing that included three other books. However, during her active botany period, before the death of her second husband in 1902, her books were very popular.

She recognized that “in England one finds books of all sizes and prices on the English ferns, while our beautiful American ferns are almost unknown, owing probably to the lack of attractive and inexpensive fern literature.” Unusual for the time, her books were both written and illustrated by women, the artists being her sister and a long-time friend. Parsons books were also noted for the covers of their bindings, designed by book cover artist Margaret Armstrong.

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

Edward Joseph Lowe (1825-1900) had the financial means to be an astronomer, a meteorologist, and an expert on ferns, the latter for him being “a matter of everyday life.” He wrote several very popular books in the last half of the 19th century, during the “fern craze” that engulfed England at the time. In “Our Native Ferns” (1867-69), he focuses on many of the highly coveted mutations, including Athyrium filix-femina var. multifidum, which he describes as “a most beautiful, symmetrical, and graceful Fern, although a monstrosity.” This book was a catalogue to these many forms, which were the most desirable objects for fern collectors.

Edward Joseph Lowe (1825-1900) had the financial means to be an astronomer, a meteorologist, and an expert on ferns, the latter for him being “a matter of everyday life.” He wrote several very popular books in the last half of the 19th century, during the “fern craze” that engulfed England at the time. In “Our Native Ferns” (1867-69), he focuses on many of the highly coveted mutations, including Athyrium filix-femina var. multifidum, which he describes as “a most beautiful, symmetrical, and graceful Fern, although a monstrosity.” This book was a catalogue to these many forms, which were the most desirable objects for fern collectors.

Lowe used a third technique for producing his images. Although his title pages lack credits, it is widely known that his images were from the printing company of Benjamin Fawcett (1808-1893) that used a centuries-old technique of wood blocks, but with a difference. Fawcett’s blocks were engraved in aged Turkish boxwood using the especially hard end grain, allowing for very fine lines and detail. For each color, a separate block was used that were carefully aligned and pressed on the page.

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

Daniel Cady Eaton (1834-1895) was a rigorous and important 19th century American botanists. He studied at Harvard University under noted botanists Asa Grey and later became a professor of botany and curator of the herbarium at Yale University. His one publication for a general audience was on a grand scale: “Beautiful Ferns from Original Water-color Drawings after Nature” (1882). This is a book to enjoy in the parlor, introducing ferns to an audience unlikely to find them by tromping in the woods. While Eaton’s writing remains academic, he occasionally digresses from his usual rather dry text, for example to describe the Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) as “one of our finest ferns.”

The illustrations are what makes this book special. The lead artist of these drawings was Charles Edward Faxon (1846-1918); a prominent American botanical illustrator based at Harvard who is best known for illustrating the 14 volume “The Silva of North America” that was written by Charles Sprague Sargent.

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865) was the first director of the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew in Britain, an institution that grew to prominence during his 24 years in that role. He was very interested in all plants and led some of the first plant explorations to isolated places in Europe, including Iceland. He was especially interested in non-flowering plants, with ferns as his favorite.

He wrote several books on ferns beginning in the 1830s, most with botanically detailed and precise descriptions spanning several volumes. In addition to his explorations, he had also had a large herbarium of preserved plant specimens from around the world, so his range was global in scope.

Recognizing the popular interest in ferns, he published for the more casual botanist and gardener “British Ferns” in 1861. He described his subjects as “general favourites with the lovers of Nature and of the horticulturist, in consequence of the extreme beauty and gracefulness of their forms.” Walter Hood Fitch (1817-1892), a protégé of Hooker’s, captured that beauty in hand-colored, lithograph images such as the Osmunda regalis or the “Osmund Royal fern.” Hooker translated “osmund” as meaning domestic peace in Saxon.

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

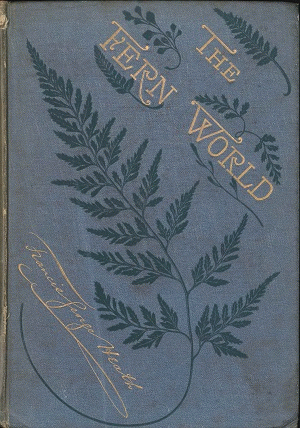

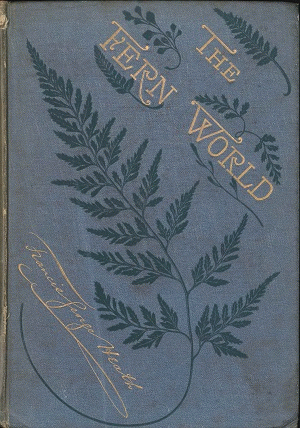

One of my favorite fern authors is Francis George Heath (1843-1913). A prolific writer, he was keen on popularizing ferns with a well-honed eye and wit. He wrote at least one book about ferns for children and in all his books, he encourages fern tourism. His favorite destination was his home shire of Devon, located in the west of England with long, wild coasts on both the English and Bristol Channels.

One of my favorite fern authors is Francis George Heath (1843-1913). A prolific writer, he was keen on popularizing ferns with a well-honed eye and wit. He wrote at least one book about ferns for children and in all his books, he encourages fern tourism. His favorite destination was his home shire of Devon, located in the west of England with long, wild coasts on both the English and Bristol Channels.

In “The Fern World” (1877), he explains his reasoning behind this push for seeking ferns in situ. “It is too frequently the custom of our botanical writers to describe with painstaking minuteness only the structure and peculiarities of the organs of plants—but tell us nothing of the life of the plants.” He was fond of pointing out contrasts, whether it be to distinguish between the rugged scenery of Devon and the “pretty, and quiet, and pastoral” look of Somerset directly to the east, or between a “Lady Fern” (Athyrium filix-faemina) and the “Male Fern” (Dryopteris filix-mas) included in the same plate. Of the former he comments, “Poets may fairly claim the right to describe the Lady Fern; for this beautiful plant is unquestionably the fairest and most delicately graceful of ferny forms, whether large or small.” He describes the “Male Fern” as so designated “on account of its remarkably erect and robust habit of growth.”

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

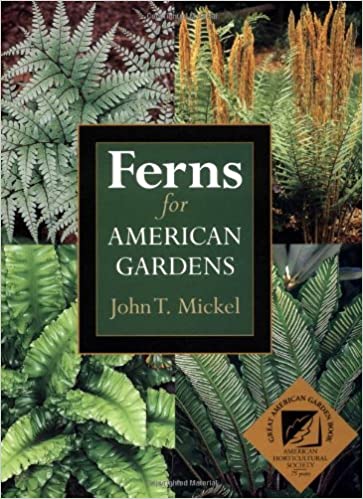

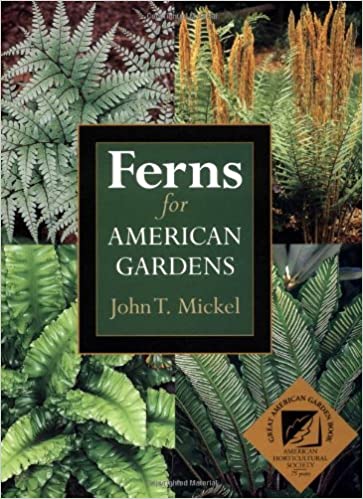

As the curator of ferns at the New York Botanical Garden, John Mickel has considerable experience with the cold hardiness of his subjects. He recognizes that his book “Ferns for American Gardens” is “not the last word on hardy fern cultivation, but only a beginning.” Despite being from the East Coast, his many garden worthy selections are vetted for suitability throughout the country, and in his acknowledgements he credits many members of the Hardy Fern Foundation, based in the Seattle area, for their input. A recommended book by local fern expert Sue Olsen.

As the curator of ferns at the New York Botanical Garden, John Mickel has considerable experience with the cold hardiness of his subjects. He recognizes that his book “Ferns for American Gardens” is “not the last word on hardy fern cultivation, but only a beginning.” Despite being from the East Coast, his many garden worthy selections are vetted for suitability throughout the country, and in his acknowledgements he credits many members of the Hardy Fern Foundation, based in the Seattle area, for their input. A recommended book by local fern expert Sue Olsen.

Published in Garden Notes: Northwest Horticultural Society, Spring 2020

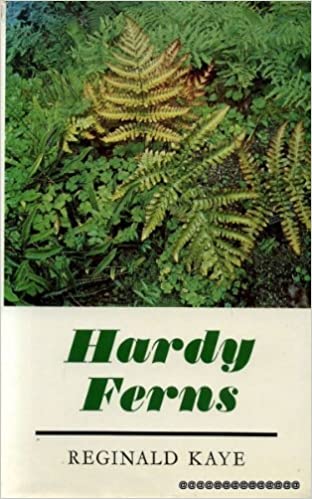

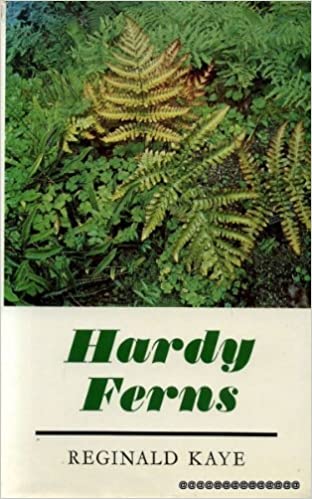

Reginald Kaye was a 20th century, English nursery owner and an expert at growing everything from orchids to alpine plants. He had both a hosta and a pulmonaria named after him, but he wrote about his favorite plants in “Hardy Ferns,” a book that helped revive something of the popularity ferns enjoyed during the Victorian period. His writing is both pragmatic and lightened by dry humor. A favorite book of local fern expert Sue Olsen.

Published in Garden Notes: Northwest Horticultural Society, Spring 2020

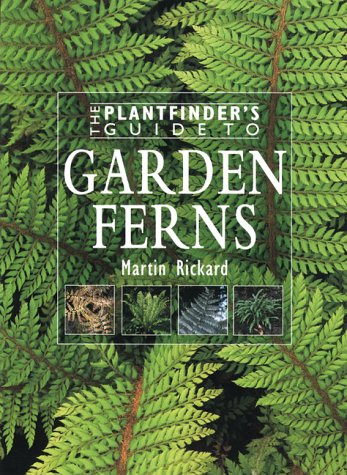

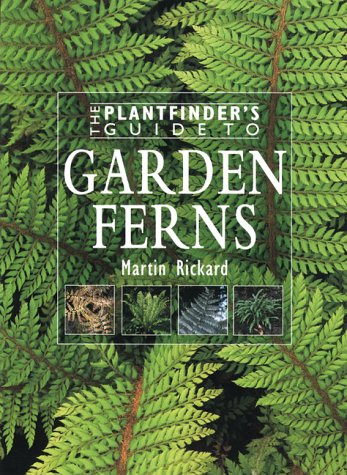

Martin Rickard’s “The Plantfinder’s Guide to Garden Ferns” includes an extensive list and description of cultivars, an obvious passion of the author and very popular with patrons of the Miller Library, as the book has been checked out over 30 times. This has excellent illustrations, including two-page plates containing several varieties for comparison; the fine foliage clearly highlighted by the lighter background. A favorite book of local fern expert Sue Olsen.

Martin Rickard’s “The Plantfinder’s Guide to Garden Ferns” includes an extensive list and description of cultivars, an obvious passion of the author and very popular with patrons of the Miller Library, as the book has been checked out over 30 times. This has excellent illustrations, including two-page plates containing several varieties for comparison; the fine foliage clearly highlighted by the lighter background. A favorite book of local fern expert Sue Olsen.

Published in Garden Notes: Northwest Horticultural Society, Spring 2020

One of the earliest fern books, ”The Ferns of Great Britain” (published in 1855), is better known for its illustrator John Edward Sowerby (1825-1870) rather than the botanist who wrote the text, Charles Johnson (1791-1880). While this was not typical, it is perhaps because Sowerby was also the publisher. There is no record of professional jealousy, as the pair produced several other books on wild flowers, poisonous plants, grasses, and useful plants found in Britain and Ireland.

One of the earliest fern books, ”The Ferns of Great Britain” (published in 1855), is better known for its illustrator John Edward Sowerby (1825-1870) rather than the botanist who wrote the text, Charles Johnson (1791-1880). While this was not typical, it is perhaps because Sowerby was also the publisher. There is no record of professional jealousy, as the pair produced several other books on wild flowers, poisonous plants, grasses, and useful plants found in Britain and Ireland. While the Victorian fern craze of late 19th century Britain had less impact in North America, one noted author who recognized the need for a guide to the ferns of the northeastern United States was Frances Theodora Parsons (1861-1952), who wrote the field guide “How to Know the Ferns” (1899). Parsons was very active in New York City and State politics and active advocate for women’s suffrage. Her autobiography, written late in her long life, talked little of her botanical writing that included three other books. However, during her active botany period, before the death of her second husband in 1902, her books were very popular.

While the Victorian fern craze of late 19th century Britain had less impact in North America, one noted author who recognized the need for a guide to the ferns of the northeastern United States was Frances Theodora Parsons (1861-1952), who wrote the field guide “How to Know the Ferns” (1899). Parsons was very active in New York City and State politics and active advocate for women’s suffrage. Her autobiography, written late in her long life, talked little of her botanical writing that included three other books. However, during her active botany period, before the death of her second husband in 1902, her books were very popular. Edward Joseph Lowe (1825-1900) had the financial means to be an astronomer, a meteorologist, and an expert on ferns, the latter for him being “a matter of everyday life.” He wrote several very popular books in the last half of the 19th century, during the “fern craze” that engulfed England at the time. In “Our Native Ferns” (1867-69), he focuses on many of the highly coveted mutations, including Athyrium filix-femina var. multifidum, which he describes as “a most beautiful, symmetrical, and graceful Fern, although a monstrosity.” This book was a catalogue to these many forms, which were the most desirable objects for fern collectors.

Edward Joseph Lowe (1825-1900) had the financial means to be an astronomer, a meteorologist, and an expert on ferns, the latter for him being “a matter of everyday life.” He wrote several very popular books in the last half of the 19th century, during the “fern craze” that engulfed England at the time. In “Our Native Ferns” (1867-69), he focuses on many of the highly coveted mutations, including Athyrium filix-femina var. multifidum, which he describes as “a most beautiful, symmetrical, and graceful Fern, although a monstrosity.” This book was a catalogue to these many forms, which were the most desirable objects for fern collectors.

One of my favorite fern authors is Francis George Heath (1843-1913). A prolific writer, he was keen on popularizing ferns with a well-honed eye and wit. He wrote at least one book about ferns for children and in all his books, he encourages fern tourism. His favorite destination was his home shire of Devon, located in the west of England with long, wild coasts on both the English and Bristol Channels.

One of my favorite fern authors is Francis George Heath (1843-1913). A prolific writer, he was keen on popularizing ferns with a well-honed eye and wit. He wrote at least one book about ferns for children and in all his books, he encourages fern tourism. His favorite destination was his home shire of Devon, located in the west of England with long, wild coasts on both the English and Bristol Channels. As the curator of ferns at the New York Botanical Garden, John Mickel has considerable experience with the cold hardiness of his subjects. He recognizes that his book “Ferns for American Gardens” is “not the last word on hardy fern cultivation, but only a beginning.” Despite being from the East Coast, his many garden worthy selections are vetted for suitability throughout the country, and in his acknowledgements he credits many members of the Hardy Fern Foundation, based in the Seattle area, for their input. A recommended book by local fern expert Sue Olsen.

As the curator of ferns at the New York Botanical Garden, John Mickel has considerable experience with the cold hardiness of his subjects. He recognizes that his book “Ferns for American Gardens” is “not the last word on hardy fern cultivation, but only a beginning.” Despite being from the East Coast, his many garden worthy selections are vetted for suitability throughout the country, and in his acknowledgements he credits many members of the Hardy Fern Foundation, based in the Seattle area, for their input. A recommended book by local fern expert Sue Olsen.

Martin Rickard’s “The Plantfinder’s Guide to Garden Ferns” includes an extensive list and description of cultivars, an obvious passion of the author and very popular with patrons of the Miller Library, as the book has been checked out over 30 times. This has excellent illustrations, including two-page plates containing several varieties for comparison; the fine foliage clearly highlighted by the lighter background. A favorite book of local fern expert Sue Olsen.

Martin Rickard’s “The Plantfinder’s Guide to Garden Ferns” includes an extensive list and description of cultivars, an obvious passion of the author and very popular with patrons of the Miller Library, as the book has been checked out over 30 times. This has excellent illustrations, including two-page plates containing several varieties for comparison; the fine foliage clearly highlighted by the lighter background. A favorite book of local fern expert Sue Olsen.