![[The Multifarious Mr. Banks] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/multifariousmrbanks300.jpg)

Joseph Banks was indeed multifarious. Webster defines the term as “having or occurring in great varieties.” Garden lovers might know that Banks became famous after collecting plants on a round-the-world voyage with Captain Cook on the Endeavour in 1768-71, and that he developed and guided Kew Gardens for decades. Toby Musgrave does justice to these huge accomplishments. What he adds is the astonishing range of other ways that Banks influenced the horticultural world – and often other worlds – in late 18th and early 19th century England and beyond.

The book is organized chronologically through the account of Banks’s Endeavour voyage and a smaller one to Iceland, but then proceeds by subject through other areas of Banks’s activities.

Banks was very wealthy. He was endlessly curious. He apparently knew everyone of any importance in England and many others on the Continent and in America. He had an outgoing and friendly personality. James Boswell describes him as “an elephant, quite placid and gentle, allowing you to get upon his back or play with his proboscis,” (p. 187), as opposed to another world traveler (Scottish explorer James Bruce) who was “a tiger that growled whenever you approached him.”

Banks was also a firm believer in progress and in empire (which 21st century readers might be less enthusiastic about). Musgrave shows us Banks’s close relationship with King George III, that nemesis of the American Revolution. “Farmer George,” as the king was called, loved Kew Gardens and walked in it with Banks regularly. In Banks’s decades-long efforts finding new plants and acquiring them for Kew, he remained focused on how plants could be used as crops or resources to aid the empire.

Banks belonged to more that 70 clubs and societies. It’s hard to imagine how he did all this and still managed his own multiple properties, regularly updating them with new planting plans. The most prominent society activity for him was his position as president of the Royal Society, a title he held for 41½ years beginning in 1778. In all these activities Banks assisted other scientists in a multiplicity of areas, giving counsel, offering connections, and sometimes providing cash.

When England needed a new site for prisoners, after Georgia was no longer available due to American independence, Banks weighed in on proposing Botany Bay in Australia as an appropriate location. He also pulled strings and even arranged smuggling a prize breed of Merino sheep from Spain, to the benefit of Australia as well as England.

Through his connections and frequent correspondence with members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham (which included Erasmus Darwin, Benjamin Franklin, and Joseph Priestly), with a great many others, and through his own study, “Banks became an acknowledged expert in a wide range of subjects including agriculture, botanic gardens, canals, cartography, coinage, colonization, currency, drainage, earthquakes, economic botany, exploration, farming, leather tanning, Merino sheep, plant pathology, and even the plucking of geese” (p. 281). Multifarious indeed.

This is a real biography, based on copious research. Musgrave avoids fictional conversations and mostly stays away from suggesting what Banks “must have thought.” Fortunately, the author is not afraid to express an opinion, such as that Banks behaved very badly in breaking his engagement to Harriet Blosset. Mostly the story Musgrave tells is one of amazing positives, ending with his justified assessment of Banks as a “great and remarkable man”(p. 332).

Published in the Leaflet, November 2021, Volume 8, Issue 11.

![[Ponderosa] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/Ponderosa300.jpg)

![[Urban Forestry & Urban Greening] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/UrbanForestry&UrbanGreeningontheshelf.jpg)

![[book title] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/anillustratedhistoryoftheherbals.jpg)

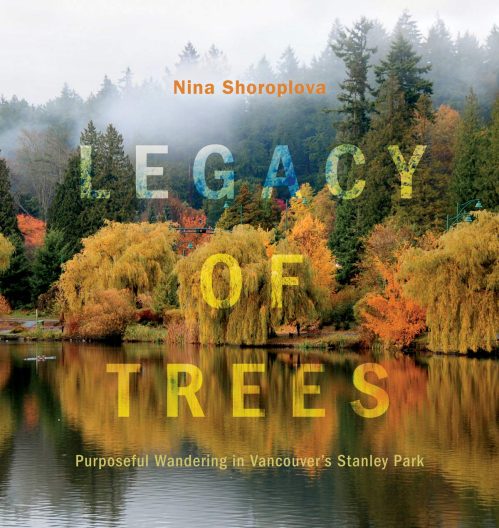

“Legacy of Trees: Purposeful Wandering in Vancouver’s Stanley Park” has an unusual way of telling the story of a public park. The intent of author Nina Shoroplova in writing the book was to allow herself the “purposeful wandering” of the sub-title. She skillfully brings the reader along on this journey, using individual trees as markers and the focus in telling the natural and human history of this peninsula and the adjacent, densely populated city.

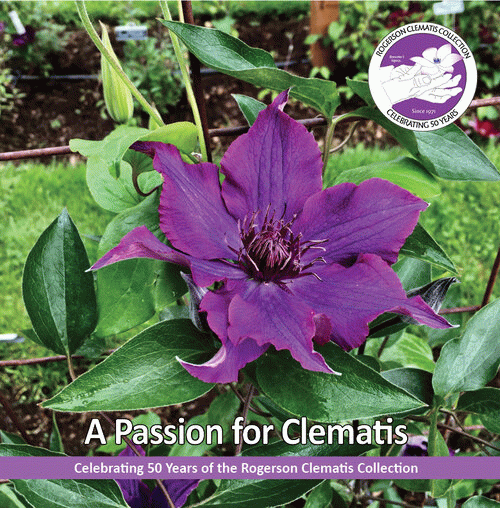

“Legacy of Trees: Purposeful Wandering in Vancouver’s Stanley Park” has an unusual way of telling the story of a public park. The intent of author Nina Shoroplova in writing the book was to allow herself the “purposeful wandering” of the sub-title. She skillfully brings the reader along on this journey, using individual trees as markers and the focus in telling the natural and human history of this peninsula and the adjacent, densely populated city. Brewster Rogerson (1921-2015) spent most of his academic career teaching English at Kansas State University. The purchase of four clematis plants began the focus of the latter part of his life, leading after retirement to his move to Oregon for a climate more conducive to his favorite genus.

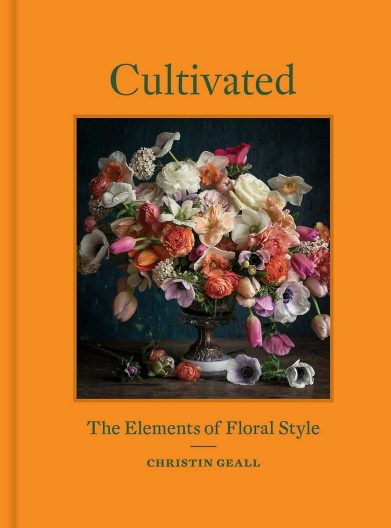

Brewster Rogerson (1921-2015) spent most of his academic career teaching English at Kansas State University. The purchase of four clematis plants began the focus of the latter part of his life, leading after retirement to his move to Oregon for a climate more conducive to his favorite genus. One tool that librarians use to organize books is the subject headings in catalog entries. For “Cultivated: The Elements of Floral Style,” the single subject heading term as provided by the Library of Congress is “flower arrangement.” While this choice is technically correct, this new book by Victoria, BC author and photographer Christin Geall is also a memoir, and explores deeper matters than most books with the same heading.

One tool that librarians use to organize books is the subject headings in catalog entries. For “Cultivated: The Elements of Floral Style,” the single subject heading term as provided by the Library of Congress is “flower arrangement.” While this choice is technically correct, this new book by Victoria, BC author and photographer Christin Geall is also a memoir, and explores deeper matters than most books with the same heading. For 15 years, the Elisabeth C. Miller Library has been hosting an exhibit by the Pacific Northwest Botanical Artists every spring. These artists keep alive a tradition of many centuries by creating scientifically accurate portrayals of the flowers, leaves, seeds, and other parts of plants, often with more detail and accuracy than a photograph.

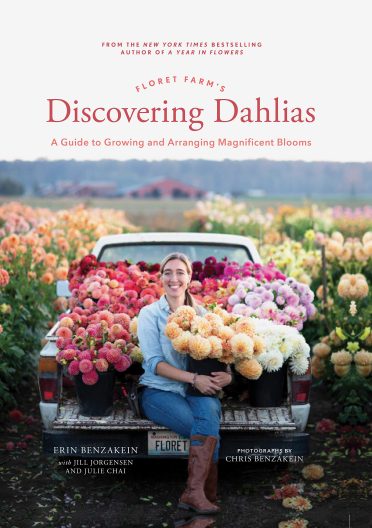

For 15 years, the Elisabeth C. Miller Library has been hosting an exhibit by the Pacific Northwest Botanical Artists every spring. These artists keep alive a tradition of many centuries by creating scientifically accurate portrayals of the flowers, leaves, seeds, and other parts of plants, often with more detail and accuracy than a photograph. We have several books on dahlias in the Miller Library collection, but none provide as much photographic detail on the different forms and the methods of growing, especially the harvesting, storing, and dividing of dahlia tubers as “Floret Farm’s Discovering Dahlias.” This how-to section also has a demonstration of hybridizing and creating your own dahlia varieties.

We have several books on dahlias in the Miller Library collection, but none provide as much photographic detail on the different forms and the methods of growing, especially the harvesting, storing, and dividing of dahlia tubers as “Floret Farm’s Discovering Dahlias.” This how-to section also has a demonstration of hybridizing and creating your own dahlia varieties.