Phaidon Press is noted for their exquisite art books, capturing in print garden subjects from many different media. “Flower: Exploring the World of Bloom” is the 4,000 year story of human fascination with flowers as told in over 300 images.

Phaidon Press is noted for their exquisite art books, capturing in print garden subjects from many different media. “Flower: Exploring the World of Bloom” is the 4,000 year story of human fascination with flowers as told in over 300 images.

Edited seamlessly by Victoria Clarke, the book begins with an insightful essay by Anna Pavord, the author of “The Tulip” and several other books that examine the human history with plants and landscapes. She does an excellent job of setting the background for the art that follows, noting that “the images in this superb collection could have been arranged by chronology or theme, but instead pictures have been cleverly paired on facing pages to highlight revealing or stimulating similarities or contrasts.”

This book is fun! You can open anywhere and immediately dive into a story told in both prose and images. It’s also huge, a hefty tome worthy of any coffee table. At first glance it might see like a lot of lovely fluff. But read on! It is an excellent and easy-to-digest history book as well as art exhibit.

A stain glass window by Louis Comfort Tiffany of wisteria looking out on Long Island’s Oyster Bay is contrasted on the opposite page with a 17th century Japanese tea pot with overglazed enamel, also depicting wisteria. A 19th century, hand-colored lithograph of a bouquet of peonies is matched with a 2011 watercolor designed to look like an herbarium specimen, also of peonies.

The subjects come from around the world and reflect developing traditions. A 1973 painting using gouache on paper is a recent stylistic example by a member of the Kwoma people of Papua New Guinea, adapting their practice of bark painting formerly used to decorate the ceilings of ceremonial buildings. This is complemented on the opposite page by the image of a bag made with glass beadwork from the last half of the 19th century. Equally colorful as the Kwoma piece, it was created by an anonymous member of the Nēhiyawak peoples of eastern Canada. The use of glass beads reflects incorporation into the native artform a new material after contact with European traders.

The book is nicely supplemented by ending appendices that include a timeline of flowers in human history, the symbolism of flowers, and short biographies of key artists represented. This is a book that takes time to digest, but that is time well spent.

Excerpted from the Summer 2021 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

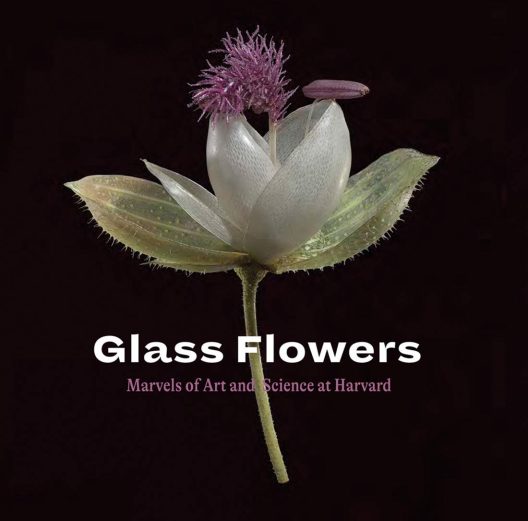

Flowers made of glass is an unusual expression of floral art, but the more than 4,300 models in the collection at Harvard University were not intended as art objects. Instead, these were teaching tools showing a selection of primarily North American native plants and frequently grown exotics for botany students in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Created by the Czech father-and-son team of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, this collection was revived by a major conservation effort and enhancement of the exhibit space over the last ten years.

Flowers made of glass is an unusual expression of floral art, but the more than 4,300 models in the collection at Harvard University were not intended as art objects. Instead, these were teaching tools showing a selection of primarily North American native plants and frequently grown exotics for botany students in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Created by the Czech father-and-son team of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, this collection was revived by a major conservation effort and enhancement of the exhibit space over the last ten years. I first glanced through “Rare Plants’ by Ed Ikin for the beautiful plant images: artwork and herbarium specimens from the vast collections of Kew Gardens dating back to the 1700s. These alone would make this book worthwhile, but there is much more. The heart of this book is a collection of essays on 40 plants from around the world that are rare or unknown in the wild. What’s surprising is that many are very familiar to gardeners in the Pacific Northwest.

I first glanced through “Rare Plants’ by Ed Ikin for the beautiful plant images: artwork and herbarium specimens from the vast collections of Kew Gardens dating back to the 1700s. These alone would make this book worthwhile, but there is much more. The heart of this book is a collection of essays on 40 plants from around the world that are rare or unknown in the wild. What’s surprising is that many are very familiar to gardeners in the Pacific Northwest.![[Grasses, Sedges, Rushes] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/Grassessedgesrushes300.jpg)

![[New Woman Ecologies] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/newwomanecologies.jpg)

![[The Garden Jungle] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/gardenjungle300.jpg)

The earliest gardeners in North America were not European settlers but the peoples of the indigenous nations, especially in our region. “All native peoples of the West Coast engaged in some form of complex and sophisticated ‘gardening’ of their homelands.”

The earliest gardeners in North America were not European settlers but the peoples of the indigenous nations, especially in our region. “All native peoples of the West Coast engaged in some form of complex and sophisticated ‘gardening’ of their homelands.” The second volume of “Flora of Oregon” continues the excellent work of volume 1, released in 2015, by focusing on the families of dicots from A to F. The third and final volume, in preparation, will be about the remaining dicot families.

The second volume of “Flora of Oregon” continues the excellent work of volume 1, released in 2015, by focusing on the families of dicots from A to F. The third and final volume, in preparation, will be about the remaining dicot families. “Gardening is not a straight line. There are many detours along the way, and thankfully, you never actually arrive at the finish.” This is a motto of Loree Bohl, a Portland gardener and author of “Fearless Gardening.”

“Gardening is not a straight line. There are many detours along the way, and thankfully, you never actually arrive at the finish.” This is a motto of Loree Bohl, a Portland gardener and author of “Fearless Gardening.” The world champion Douglas-fir in height is found in Coos County, Oregon. But what if your interest lies in smaller trees? For example, the tallest vine maple (Acer circinatum) in the country is 46’ high and found in Clatsop County, Oregon. This detail, along with many, many others can be found in “Oregon: Big Tree & Shrub Measurements” by Jack Black.

The world champion Douglas-fir in height is found in Coos County, Oregon. But what if your interest lies in smaller trees? For example, the tallest vine maple (Acer circinatum) in the country is 46’ high and found in Clatsop County, Oregon. This detail, along with many, many others can be found in “Oregon: Big Tree & Shrub Measurements” by Jack Black.