This Journal is the account of David Douglas, a Scottish plant explorer in our region during the 1820s and 1830s. Douglas was famous for introducing several conifers to Europe; however he described all the shrubby and herbaceous species he observed, too.

This transcription was not published until 1914 by the Royal Horticultural Society. Why the delay? The secretary of the RHS, W. Wilks, states in the preface that the original was very difficult to decipher as the handwriting was “occasionally almost if not quite impossible” to read.

Reading the results of this effort, I found that he writing style by Douglas is not romantic, but is mostly an accounting of the weather (often in dour terms), his meals (often meager), and the course of his travels. Animals described are mostly ones he killed. An exception being mosquitoes with which he was “dreadfully annoyed.” More interesting are his encounters with indigenous people who sometimes helped him with his exploration, but the real focus was on the plants he found and described.

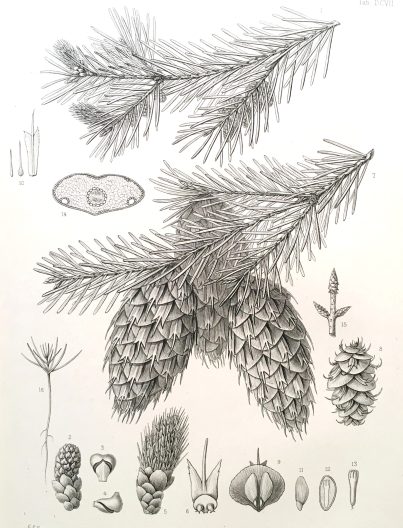

While most famous for conifers, most of the plants he described are herbaceous species, typically in brief terms, although he sometimes notes the potential ornamental value for gardeners. This compilation includes other, more formal manuscripts by Douglas. One gives his impressions of American pines. This included trees now considered to be spruce (Picea sp.), true firs (Abies sp.), and his eponymous Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii).

Although never lyrical, Douglas comes close as he describes the ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) as “highly ornamental” and that “it never grows in nor composes thick forests like the Abies section, but is found on declivities of low hills and undulating grounds in unproductive sandy soils in clumps, belts, or forming open woods, and in low, fertile, moist soils totally disappears.”

Reviewed by: Brian Thompson on February 24, 2025

Excerpted in part from the Spring 2025 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

This research took over a decade at the turn of the 20th century and was still the authority almost 50 years later when this set was published. It served as an important reference work for the Arboretum library and is still of value today, especially for the exquisite illustrations by Charles Edward Faxon, who accompanied Sargent on his research trips.

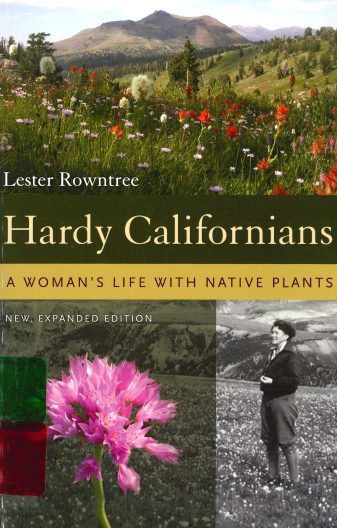

This research took over a decade at the turn of the 20th century and was still the authority almost 50 years later when this set was published. It served as an important reference work for the Arboretum library and is still of value today, especially for the exquisite illustrations by Charles Edward Faxon, who accompanied Sargent on his research trips. The author said it the best. “This is not ‘another garden book.’ Nor is it a handbook of California wild flowers. What I have tried to do is to convey to those who garden, as well as those who don’t, something of the loveliness and the garden possibilities of certain less familiar hardy native plants of California.”

The author said it the best. “This is not ‘another garden book.’ Nor is it a handbook of California wild flowers. What I have tried to do is to convey to those who garden, as well as those who don’t, something of the loveliness and the garden possibilities of certain less familiar hardy native plants of California.” The author said it the best. “This is not ‘another garden book.’ Nor is it a handbook of California wild flowers. What I have tried to do is to convey to those who garden, as well as those who don’t, something of the loveliness and the garden possibilities of certain less familiar hardy native plants of California.”

The author said it the best. “This is not ‘another garden book.’ Nor is it a handbook of California wild flowers. What I have tried to do is to convey to those who garden, as well as those who don’t, something of the loveliness and the garden possibilities of certain less familiar hardy native plants of California.” The author said it the best. “This is not ‘another garden book.’ Nor is it a handbook of California wild flowers. What I have tried to do is to convey to those who garden, as well as those who don’t, something of the loveliness and the garden possibilities of certain less familiar hardy native plants of California.”

The author said it the best. “This is not ‘another garden book.’ Nor is it a handbook of California wild flowers. What I have tried to do is to convey to those who garden, as well as those who don’t, something of the loveliness and the garden possibilities of certain less familiar hardy native plants of California.” A most interesting book in the Miller Library is “Chilean Flora through the eyes of Marianne North 1884.” Published in Chile in 1999, originally in Spanish, we have the English translation that is an account of the artist’s visit to Chile, the last of her journeys. As authors Antonia Echenique (a Chilean historian) and María Victoria Legassa (a Chilean sociologist) explain, her work was not previously well-known but, upon her visit, she “attracted the attention of a number of contemporary Chilean intellectuals and scientists.”

A most interesting book in the Miller Library is “Chilean Flora through the eyes of Marianne North 1884.” Published in Chile in 1999, originally in Spanish, we have the English translation that is an account of the artist’s visit to Chile, the last of her journeys. As authors Antonia Echenique (a Chilean historian) and María Victoria Legassa (a Chilean sociologist) explain, her work was not previously well-known but, upon her visit, she “attracted the attention of a number of contemporary Chilean intellectuals and scientists.” Her visits were not rushed; staying in one place for a long time, including a year or more each in Brazil, India, and Australasia. She came near our region in 1875 while painting the coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervivums) in northern California.

Her visits were not rushed; staying in one place for a long time, including a year or more each in Brazil, India, and Australasia. She came near our region in 1875 while painting the coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervivums) in northern California. With a nice sense of humor, Whyman describes how she worked months and then years, and spent considerable money, to restore the meadow. In her concern for the desirable plants, animals, and insects on her property Whyman at first resisted controlled burns and herbicides. One invasive plant that helped modify her views was the blackberry – wildly invasive here in western Washington, too. She came to accept the burns but continued to limit herbicides to the least amount she could, feeling anguish at every drop applied.

With a nice sense of humor, Whyman describes how she worked months and then years, and spent considerable money, to restore the meadow. In her concern for the desirable plants, animals, and insects on her property Whyman at first resisted controlled burns and herbicides. One invasive plant that helped modify her views was the blackberry – wildly invasive here in western Washington, too. She came to accept the burns but continued to limit herbicides to the least amount she could, feeling anguish at every drop applied.