In the nineteenth century, Canadian women got their hands dirty in lots of botanical projects.

Flora’s Fieldworkers, edited by Ann Shteir, fills some gaps in the history of these women’s work. The book grew out of a 2017 workshop, “Women, Men, and Plants in nineteenth-century Canada,” at York University in Toronto.

Some women in this volume collected plants. A few sent plant samples to William Jackson Hooker at Kew Gardens in England for his

Flora Boreali–Americana and to other plant seekers. Several women established or participated in organizations promoting or educating about botany and horticulture. Others produced botanic or floral art – paintings, albums, quilts. Nearly all gardened.

Flora’s Fieldworkers describes these endeavors, often placing them in a context of pushing the boundaries of the roles socially prescribed for women. Gardening and floral art were women’s work. Everything else in botany required women skillfully to insert themselves into the male-dominated establishment.

Christian Ramsay (1786-1839), the Countess of Dalhousie, amassed great quantities of plant specimens in Canada (and India and Scotland). Some are still preserved in several herbaria. She sent samples to Hooker, which he used. Like almost all the women in this volume, Lady Dalhousie taught herself botany, and she became expert. Her collecting opportunities came as she followed her husband’s diplomatic career. In her case, as in others, the author reminds us that England’s empire-building hovered in the background.

Catherine Parr Traill (1802-1899) was the most famous woman in this collection, though much of her fame grew from her work as a children’s author and natural historian. Plants played a large role in such works as her The Backwoods of Canada, along with the birds and small animals. She combined careful and accurate plant descriptions with the context of her own sense of connection. If she could not find a new plant described in her small botanical library, she happily invented her own name for it.

Traill began collecting plants soon after her arrival in Canada from England in 1832, continuing for seven decades and writing detailed descriptions of each. With the help of her niece, Agnes Fitzgibbon, Traill published two volumes (both using standard nomenclature),

Canadian Wild Flowers (in the Miller Library’s Tall Shelves) and

Studies of Plant Life in Canada , in the rare book collection. Both titles are digitized and available online.

Ramsay, Fitzgibbon, and Traill join numerous others in this enlightening volume on early women botanists up north.

Reviewed by Priscilla Grundy in Leaflet for Scholars, Volume 10, Issue 7, July 2023

One of my favorite books in the Miller Library collection is Beth Chatto’s Gravel Garden. Published in 2000, it recounts the development of a formerly grassy parking area into a garden with gravel used as mulch, and no irrigation once plantings were established.

One of my favorite books in the Miller Library collection is Beth Chatto’s Gravel Garden. Published in 2000, it recounts the development of a formerly grassy parking area into a garden with gravel used as mulch, and no irrigation once plantings were established. One of my favorite books in the Miller Library collection is Beth Chatto’s Gravel Garden. Published in 2000, it recounts the development of a formerly grassy parking area into a garden with gravel used as mulch, and no irrigation once plantings were established.

One of my favorite books in the Miller Library collection is Beth Chatto’s Gravel Garden. Published in 2000, it recounts the development of a formerly grassy parking area into a garden with gravel used as mulch, and no irrigation once plantings were established. Jeff Lowenfels was immersed in gardening and small-scale farming as a child in upstate New York. He completed an undergraduate degree at Harvard in Geology, and later earned a law degree at Northeastern University focused on environmental law. With this background, it is perhaps surprising that he has lived most of his adult life in Anchorage, Alaska. Now retired from practicing law, he continues to write a long-running (over 45 years) gardening column in the “Anchorage Daily News.”

Jeff Lowenfels was immersed in gardening and small-scale farming as a child in upstate New York. He completed an undergraduate degree at Harvard in Geology, and later earned a law degree at Northeastern University focused on environmental law. With this background, it is perhaps surprising that he has lived most of his adult life in Anchorage, Alaska. Now retired from practicing law, he continues to write a long-running (over 45 years) gardening column in the “Anchorage Daily News.” In the nineteenth century, Canadian women got their hands dirty in lots of botanical projects.

In the nineteenth century, Canadian women got their hands dirty in lots of botanical projects.  Hens-and-chicks were one of the first garden plants I came to recognize in childhood. However, compared to the brightly colored tulips and glads I favored; I didn’t think much of them. I was amused by the offsets (the “chicks”) that formed easily around the central plant (the “hen”), but the leaves were typically a dull green and the plants only occasionally sent up undistinguished flowers.

Hens-and-chicks were one of the first garden plants I came to recognize in childhood. However, compared to the brightly colored tulips and glads I favored; I didn’t think much of them. I was amused by the offsets (the “chicks”) that formed easily around the central plant (the “hen”), but the leaves were typically a dull green and the plants only occasionally sent up undistinguished flowers. “Julia” is a graphic biography of Julia Henshaw (1869-1937), who published the first book on the wild flowers of the Canadian Rockies in 1906. This was a relatively small aspect of her colorful life and author/illustrator Michael Kluckner chose her later role as an ambulance driver in World War I for his book’s cover.

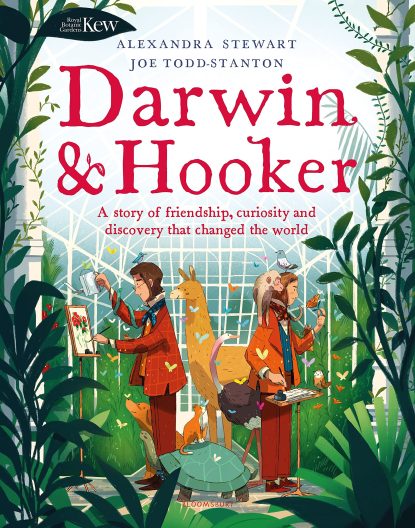

“Julia” is a graphic biography of Julia Henshaw (1869-1937), who published the first book on the wild flowers of the Canadian Rockies in 1906. This was a relatively small aspect of her colorful life and author/illustrator Michael Kluckner chose her later role as an ambulance driver in World War I for his book’s cover. Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817-1911) were both major figures in 19th century British biology. Darwin is famous for his work on evolution, and Hooker was an important plant explorer and director of Kew Gardens, following his father William Jackson Hooker in that position.

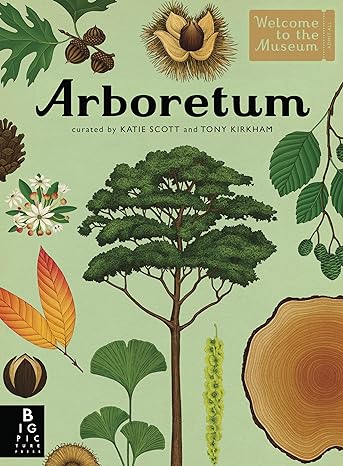

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817-1911) were both major figures in 19th century British biology. Darwin is famous for his work on evolution, and Hooker was an important plant explorer and director of Kew Gardens, following his father William Jackson Hooker in that position. “Arboretum” is a new book this spring in the “Welcome to the Museum” series from Big Picture Press. The Miller Library has three titles in this series, all illustrated by Katie Scott, collaborating with different text authors.

“Arboretum” is a new book this spring in the “Welcome to the Museum” series from Big Picture Press. The Miller Library has three titles in this series, all illustrated by Katie Scott, collaborating with different text authors. The most distinctive of the graphic nonfiction books in the Miller Library collection is “Mycelium Wassonii” by Brian Blomerth. It is a biography of R. Gordon Wasson (1898-1986) and Valentina Pavlovna “Tina” Wasson (1901-1958). Their careers were in banking and pediatrics, respectively, however they are best known for the passionate interest in the significance of mushrooms to different cultures around the world and as pioneers in the study of ethnomycology.

The most distinctive of the graphic nonfiction books in the Miller Library collection is “Mycelium Wassonii” by Brian Blomerth. It is a biography of R. Gordon Wasson (1898-1986) and Valentina Pavlovna “Tina” Wasson (1901-1958). Their careers were in banking and pediatrics, respectively, however they are best known for the passionate interest in the significance of mushrooms to different cultures around the world and as pioneers in the study of ethnomycology. All members of the plant kingdom are supported by members of the kingdom of fungi. To learn more about these sometimes very different lifeforms, read “Humongous Fungus,” illustrated by Wenjia Tang and written by Lynne Boddy.

All members of the plant kingdom are supported by members of the kingdom of fungi. To learn more about these sometimes very different lifeforms, read “Humongous Fungus,” illustrated by Wenjia Tang and written by Lynne Boddy. What do you know about plant evolution? My hazy memories from introductory college biology center on the development of animals, while plants got short shrift. For an easy and entertaining way to fill this gap, I found “When Plants Took over the Planet” an excellent solution. Illustrator Amy Grimes and text author Chris Thorogood start with very small algae, then show how these evolved into a group of plants that includes the seaweeds, such as the giant kelp (Macrocystits pyrifera) that can grow 24 inches in a single day.

What do you know about plant evolution? My hazy memories from introductory college biology center on the development of animals, while plants got short shrift. For an easy and entertaining way to fill this gap, I found “When Plants Took over the Planet” an excellent solution. Illustrator Amy Grimes and text author Chris Thorogood start with very small algae, then show how these evolved into a group of plants that includes the seaweeds, such as the giant kelp (Macrocystits pyrifera) that can grow 24 inches in a single day.