Books about Chilean gardens and plants are rare, especially in English. So it is particularly exciting to have a new book, this being about the country’s native flora. “Plants from the Woods and Forests of Chile” was published by the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and includes 81 exquisite plates of Chilean plants, each with engaging, full page write-ups that include the importance of the plant both to native peoples and in today’s culture, its ecological niche and conservation status, and general propagation and cultivation advice.

All of the selections are also quite beautiful, and the botanical artistry is of the finest quality. Many of the plants are familiar, including Arboretum plants such as monkey puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana) and Chilean firebush (Embothrium coccineum). This publication is very much of the quality and in the style (and large size) of the great 18th and 19th century floras and as with those, we keep it in the rare book room of the Miller Library where it is available for viewing by appointment.

Excerpted from the Spring 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

Central Chile is represented by one of the five gardens in Pacific Connections. As garden-related books published in Chile are rare, I decided to review a book (in both English and Spanish) by and about a Chilean landscape architect, Teresa Moller. In this beautifully photographed and oversize (and therefore non-lending) book, I was surprised to find much that reminds me of Mediterranean designs.

“Unveiling the Landscape” extends beyond the central, Mediterranean climate zone to the very stark and extremely dry Atacama Desert in northern Chile, and to Moller’s own forest home in the Lakes District of south-central Chile. The projects also range in the original condition of the sites, from nearly pristine, rocky coasts to areas long used for agriculture. In all of these, her designs show respect for the existing environment, whether natural or human-made. Often it takes a careful study of the photographs to discern her work from the original landscape.

I found the most intriguing project to be at Punta Pite, where a pathway begins at the Pacific Ocean, climbs up through rocky cliffs and rough woodlands, and eventually to a park of old cypress trees. Dutch landscape architect Michael Van Gessel described it in this way, “It is obvious that Teresa did not look for variety but simply discovered and displayed the existing variety in the landscape. This she achieved in both a most restrained and at times dramatic way. Landscape scenography at its highest level. The coastal pathway Punta Pite is sheer poetry in stone.”

Excerpted from the Spring 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

For those interested in the gardens of Provence or in gardening anywhere along the northern shore of the Mediterranean, the books of Louisa Jones may already be very familiar. She writes in both French and English from her base in southern France. What I learned recently is that she lived in Seattle for many years, teaching literature at the University of Washington.

The Miller Library has seven of the books by this author, mostly on gardens in France, including French vegetable and kitchen gardens. The most recent, “Mediterranean Landscape Design,” expands her scope into neighboring countries and focuses on the human influence on the landscape, including many examples that may seem natural, but instead are the results of centuries of human activities with the land.

I found the chapter on clipped greenery particularly enlightening, as I’ve never fully appreciated the formal gardens I’ve seen in Mediterranean countries. Jones explains that in this region, the many native, broadleaf evergreens “…are already mounded by wind, drought, sheep, fire and frost.” Farmers prune these plants further for windbreaks. “When architects and sculptors then organize them into shapes and masses, topiary and parterres, they are not choosing artifice over nature, the tame versus the wild, but merely going one step further than the farmers into human intervention.”

Throughout the book there are many other examples of gardening with nature rather than trying to subdue it. This approach tends to deemphasize flowers, which are often fleeting in this climate, and makes “…no distinction between ornamental and productive gardening.” The author emphasizes this point as she thinks that “…Northern European cultures have effectively separated the two.”

Excerpted from the Spring 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

I picked up “The Natural World of Winnie-the-Pooh”, expecting it to be lightweight and quick to read, but instead I became enchanted and deeply engaged. The author, Kathryn Aalto, is a former Pacific Northwest resident (she taught at Western Washington University and Everett Community College) who now lives in England.

Almost any list of the best English books for children will include “Winnie-the-Pooh” (1926) and “The House at Pooh Corner” (1928) by A. A. Milne. Much of the inspiration for the places in these books comes from real places in the Ashdown Forest, southeast of London, and from the nearby farm where Milne and his family—including his son Christopher Robin—lived.

After setting the stage with a biography of Milne and of the illustrator, E. H. Shepard, author Aalto gives a detailed review of the story elements as they relate to real places. Fortunately, these places have been little changed in 90 years: “There are no overt signs pronouncing your arrival in Pooh Country. There are no bright lights or billboards, no £1 carnival rides, no inflatable Eeyores, Owls, or Roos rising and falling in dramatic flair.”

The last third of the book is essentially a field guide to the Ashdown Forest, including its natural and cultural history. One thing you learn is that despite the name, there are no ash trees, and much of the land is not forested, but it is a place of considerable biodiversity despite much human intervention over many centuries.

Excerpted from the Spring 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

Curtis Stone, the author of “The Urban Farmer”, sums up the purpose of his book with a most succinct subtitle: “Growing Food for Profit on Leased and Borrowed Land.” This is a manual for a very specific but growing audience. While there are many books to provide inspiration for would-be urban farmers, I don’t know of any other that is so detailed in the nuts and bolts of turning this activity into a part- or full-time livelihood.

Gardening advice is mostly on crop rotation and timing, most profitable selections, and the preparation of the harvest for sale – all key points in running a business. Chapters cover market streams, labor, self-promotion, and finance options. The author is clear that there’s no point in doing this unless you eventually make a living at it. He also warns to start small, don’t overextend yourself, and be realistic about the demands on your time and finances.

Stone lives in Kelowna, British Columbia, a city of 117,000, but he is familiar with the needs and challenges of farming in both larger, denser cities and on what he calls peri-urban land: the larger, often 1-2 acre lots where the suburbs make the transition into the rural countryside. He gives the pros and cons of having all your crops at one site (often not possible in an urban setting), or the more likely model of having multiple plots.

How do you find these plots? He has several suggestions and provides a 10-point checklist to consider for each potential site. Before you begin reviewing the list, he does bend a bit from his typical, matter-of-fact tone by reminding the reader that you as a farmer are valuable. “Approach all negotiations [with landowners] from a place of abundance. You are the one in demand, because you are scarce. Land is abundant!”

Excerpted from the Spring 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

There are several books in the Miller Library collection on the wild berries and similar fruit of the native plants of the Pacific Northwest. However, none of these are recent, so it is delightful to add “Wild Berries of Washington and Oregon” to the collection, especially as it is published by Lone Pine, which has a history of publishing excellent field guides with nearly weatherproof covers, for exploring our region.

T. Abe Lloyd and Fiona Hamersley Chambers have created a practical guide to finding, foraging, and savoring the bounty of our local berries. It is a beautiful book, too, with excellent close-up photographs. If these don’t make your mouth water, the authors’ favorite recipes—and they are both experienced foragers—surely will.

This is not an ethnobotany book, although both of the authors studied with noted ethnobotanist Nancy Turner at the University of Victoria. It is not surprising that the entries in this book include the historical, Native American uses of each fruit, including the management of the prized plants that produce them. This includes more recent adaptations native peoples learned from Europeans, such as this treatment of red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea) berries: “They were also occasionally stored for winter use, either alone or mashed with sweeter fruits such as serviceberries, and in more modern times with sugar.”

Berries are defined here in the popular sense, so included are drupes, pomes, and a few other fruits such as rose hips and juniper “berries”. Escaped and invasive berry producing plants such as the several types of introduced blackberries (Rubus species) are given equal treatment since you’ll easily find these, and most are tasty. Poisonous berries are carefully described, as are toxic parts of plants bearing edible fruit.

Excerpted from the Spring 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

Linda Chalker-Scott, the urban horticulturist for Washington State University Extension and author of “How Plants Work,” uses both her own experience as a gardener and her education and research as a scientist to look at gardening aesthetically and at the molecular level. The result is very user-friendly way to learn more about how your garden operates from the perspective of the plants (and the bugs and the fungi, etc.).

That’s not to say this is easy reading. To get the most out of this book you need to spend time learning some terminology and concepts not typically needed when shopping in your local garden center. This effort will be worthwhile, as the author is very keen to steer you away from using products that will waste your money or damage your plants. She does all of this with humor and good examples which often come from her own garden in Seattle.

Her verbal illustrations are often quite vivid. “Imagine your head is an oxygen atom and your hands are hydrogen atoms, joined by your arms in between (the bonds). Now make a Y with your arms (perhaps performing a molecular version of The Village People’s ‘YMCA’).” After you’ve stopped singing this ditty, you’ll continue reading, but now with a nifty mnemonic to remember the cohesive and adhesive properties of water.

Throughout, Chalker-Scott is enthusiastic about plants. In a world that seems to favor animals, they have done quite well, managing “to use every body part and exploit animals as well as the forces of nature to ensure their spread into every environment.” All this is an “amazing accomplishment by a life form that’s literally rooted in place.”

Excerpted from the Spring 2016 Arboretum Bulletin.

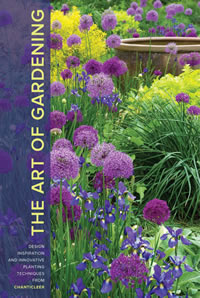

In June 2005, I attended a conference for plant science librarians in Philadelphia. After a long day of presentations, business meetings, and visits to libraries, I wasn’t expecting much from a visit to small garden west of the city near Villanova University.

In June 2005, I attended a conference for plant science librarians in Philadelphia. After a long day of presentations, business meetings, and visits to libraries, I wasn’t expecting much from a visit to small garden west of the city near Villanova University.

Instead, that evening at Chanticleer was one of the most magical garden experiences of my lifetime. The weather was perfect, cooled down from the already warm and humid beginning of summer. A glass of wine and a convivial group of colleagues added to the good feelings, but mostly it was the stunning garden rooms, plantings, and artwork of this most amazing garden.

Now there is an exciting new book, “The Art of Gardening”, which takes its place among the best of all garden profiles. Written by R. William Thomas and the horticultural staff of Chanticleer, this not only transports the reader to the garden, it is also an excellent source of design ideas and plant choices for your own garden. I don’t purchase many gardening books for my home library since I have daily access to the Miller Library collections, but this is one that I will get for sure.

Published in the March 2016 Leaflet Volume 3, Issue 3.

Stuart Echols and Eliza Pennypacker are on the faculty of the Department of Landscape Architecture at Penn State University. They have combined their academic interests in stormwater management and sustainable landscapes to write “Artful Rainwater Design”.

Much of the tone of the book is captured in this quotation about changing terminology: “Stormwater—a waste product and common enemy blamed for property damage through flooding and for surface water and aquatic system damage through pollutant conveyance—has morphed into rainwater, a valued natural resource beneficial to our water cycle.” Techniques, design principles, dealing with public relations, and many case studies—including several in the Pacific Northwest—make this an important book for anyone involved with any aspect of water management in urban settings.

Published in the March 2016 Leaflet for Scholars Volume 3, Issue 3.

Edible Heirlooms is a great little book! Little only in dimensions and number of pages, as the author carefully defines his purpose and limits his scope, but within those parameters shows you how to grow an outstanding vegetable garden in the maritime Pacific Northwest.

Edible Heirlooms is a great little book! Little only in dimensions and number of pages, as the author carefully defines his purpose and limits his scope, but within those parameters shows you how to grow an outstanding vegetable garden in the maritime Pacific Northwest.

Most important, he sees this endeavor as part of a larger picture. “The challenge for me is to somehow integrate my vegetable-growing practices into a diverse ecosystem and, if possible, enhance biodiversity.” The key for this is to use heirloom varieties that can be regrown from collected seeds. Besides the mouth-watering descriptions, you will also get an excellent history lesson.

In June 2005, I attended a conference for plant science librarians in Philadelphia. After a long day of presentations, business meetings, and visits to libraries, I wasn’t expecting much from a visit to small garden west of the city near Villanova University.

In June 2005, I attended a conference for plant science librarians in Philadelphia. After a long day of presentations, business meetings, and visits to libraries, I wasn’t expecting much from a visit to small garden west of the city near Villanova University.