Amy Stewart has written several books that are in the Miller Library, covering a wide-range of plant-related topics. She is also an author of historical novels, and she brings that skill of writing narratives to all her books. Her latest, The Tree Collectors: Tales of Arboreal Obsession, showcases two additional talents: her ability to conduct insightful interviews and to draw illustrations of both people and plants.

This book represents the author’s process of discovery about the many ways people relate to trees. The results are much more varied than Stewart guessed when she began. Some were expected, such as an individual with sufficient land planting all the species in a genus, or all the trees associated together for some other reason.

Others document all the trees of a place. Some plantings are memorials; others are to promote sustainable forestry. Using trees for bonsai or topiary describes the passion of two collectors, while another has amassed no live trees but nearly 7,000 wood samples.

I found the work of Kenneth Høech of Narsarsuaq in southern Greenland especially fascinating. He has researched trees that survive near the arctic tree line and has begun an arboretum to give this otherwise treeless island arboreal plant life.

Sam Van Aken of Syracuse, New York engaged in a project called Tree of 40 Fruit. He grafted stone fruits, including plums, cherries, apricots, almonds, and peaches, onto a single tree, and planted these at suitable locations throughout the country. Each of the typically historical varieties is documented in his archive of botanical illustrations and herbarium specimens of the leaves and flowers.

I recommend this book for its many fascinating stories. As Amy Stewart concludes in her introduction, “if this book accomplishes anything, I hope it inspires you to plant a tree. Or two. Or maybe a dozen. Watch out, though—trees can be addictive.”

Published by Brian Thompson in Leaflet for Scholars, Volume 12, Issue 1, January 2025.

Did you know that skunk cabbage roots look like pale, ropy space aliens? Would you like to learn to make maple syrup from bigleaf maple sap? How about some rose-petal honey for your next tea party?

Did you know that skunk cabbage roots look like pale, ropy space aliens? Would you like to learn to make maple syrup from bigleaf maple sap? How about some rose-petal honey for your next tea party?

The life and work of Marianne North, the eminent Victorian botanical artist, is well documented. Do we need another book about her? Michelle Payne provides a positive answer in this well-illustrated volume. She aims to modify the dominant image of North as an intrepid lone traveler to the many sites of her art, to show us a different, fuller picture. North always had a cast of helpers around her and benefited from her colonial connections.

The life and work of Marianne North, the eminent Victorian botanical artist, is well documented. Do we need another book about her? Michelle Payne provides a positive answer in this well-illustrated volume. She aims to modify the dominant image of North as an intrepid lone traveler to the many sites of her art, to show us a different, fuller picture. North always had a cast of helpers around her and benefited from her colonial connections.

youngest of readers, and the word ‘colored’ is a pointed, satirical use of an antiquated term. The second half of the title indicates the book’s purpose: An Alphabetary of the Colonized World. In form, the book calls to mind children’s books of centuries past, which were meant as vehicles of moral education. This aim is true here, too, but the content is distinctive for its intense focus on plant discovery and naming in the historical context of conquest, colonial exploitation, and slavery. This book is a necessary counter-narrative to traditional white Eurocentric perspectives on botany and human-plant relationships.

youngest of readers, and the word ‘colored’ is a pointed, satirical use of an antiquated term. The second half of the title indicates the book’s purpose: An Alphabetary of the Colonized World. In form, the book calls to mind children’s books of centuries past, which were meant as vehicles of moral education. This aim is true here, too, but the content is distinctive for its intense focus on plant discovery and naming in the historical context of conquest, colonial exploitation, and slavery. This book is a necessary counter-narrative to traditional white Eurocentric perspectives on botany and human-plant relationships. For students contemplating a career in the plant sciences, being a forensic botanist is probably not at the top of the prospective career list. Reading

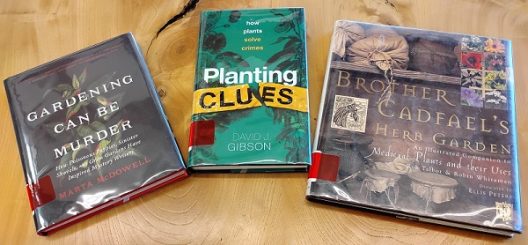

For students contemplating a career in the plant sciences, being a forensic botanist is probably not at the top of the prospective career list. Reading