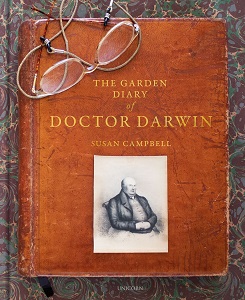

This handsome book presents for the reader the garden diary of Dr. Robert Darwin, father of the famous Charles. Subtitled “A Garden History,” it brings to life the garden Charles knew as a child. As such it has some interest in how the garden might have related to Charles’s thinking about evolution and how he occasionally used the garden for plant experiments. Its primary interest, though, is as a description of a very impressive mid-19th century garden.

This handsome book presents for the reader the garden diary of Dr. Robert Darwin, father of the famous Charles. Subtitled “A Garden History,” it brings to life the garden Charles knew as a child. As such it has some interest in how the garden might have related to Charles’s thinking about evolution and how he occasionally used the garden for plant experiments. Its primary interest, though, is as a description of a very impressive mid-19th century garden.

Susan Campbell divides the book into three parts, the first intended for garden enthusiasts, the second for “keen garden enthusiasts,” and the third for “even more serious garden enthusiasts.” Part One is the history of the garden; Part Two contains entries from the diary itself; and Part Three catalogues all the plants mentioned in the diary. As a member of only her first reader category, I can testify that all three are worthy of attention.

In 1796 Robert Darwin purchased the property near Shrewsbury that would officially become The Mount House and the site of the garden. He had recently married Susannah Wedgwood of the famous pottery family, and her money undoubtedly underwrote the purchase, though he had a thriving medical practice. On a cliff overlooking the Severn River, the site had previously been a “rubbish tip.” Given the Miller Library’s similar history of construction on a garbage dump, readers may feel connected. The garden, about seven acres when completed, included a large kitchen garden and a flower garden. A greenhouse was attached to the residence.

Charles Darwin’s recorded experiences with the garden begin with his father asking him, at age 10, to count the flowers on the peony plants (160 in 1810). While he was on his famous voyage on the “Beagle,” letters from his sisters provide much information on the garden development, and one from Charles reports he would love to be back in the gardens “’like a Ghost amongst you’” (p. 38). The Diary itself begins on September 1, 1838 and ends in 1866. It includes several references to experiments with plants requested by Charles, who was living in London, with no garden. In January 1939, for instance, Dr. Darwin records sowing Mimosa sensitiva in the family hothouse for his son.

Part One of “Dr. Darwin’s Diary” also includes descriptions of the various gardens and background on the Darwin family in Shrewsbury. Campbell turned up lots of intriguing information for this book. One example: Dr. Darwin weighed 24 stone later in life. A stone is 14 pounds! He had to be wedged into the carriage that took him on his medical rounds. He clearly was not “cleaning” the garden himself. (They didn’t call it weeding.)

Part Two, “An Almanac of Work done in the Garden,” lists items by months through the year, under categories like “Work Under Glass (Indoors),” and “Walks and Lawns.” Extracts from multiple years are presented under each category. Specific dates are not always included, but for November, in the “Fields” category, Campbell notes that “The haystack is cut for the first time” appears in the diary in 1842,1844, and 1852.

This section of the book provides a wonderful, detailed description of the work in the garden and the rhythm of the seasons. Campbell connects entries to various events in the garden and elsewhere. When the diary notes that asparagus and globe artichokes are cut down and covered in cedar boughs, she explains that the boughs “undoubtedly” came from a cedar tree blown down the previous winter (p. 164).

Rarely “Special Events” are included. A Thanksgiving Day decreed by Queen Victoria for November 11, 1849, comes with Campbell’s explanation that it marked the end of a cholera epidemic. Most entries record the routine activities of planting, tending, harvesting, and maintaining the garden.

Part Three – “A Catalogue of Plants named in the Diary” – divides the plants into five categories. Roses have one of their own; three are organized by their location in the garden, e.g., the Green House; and a final catch-all category of flowers and shrubs named elsewhere in the diary. Each entry uses the plant’s name and spelling found in the diary, and its location and source, if known. In a section on Citrus Trees, Campbell sometimes adds background information: The Shaddock tree is a native of China and Japan, for example, and the “sweet lemon” cut down in 1849, came from the doctor’s niece. Descriptions may also note how and where the plant was grown, such as the pineapple plant being potted and plunged into tar in the greenhouse.

In sum, The Garden Diary of Dr. Darwin provides not only a wealth of botanical information, but also a precise history of this particular garden and its connection to the Darwin family and to the social environment that supported it.

Published in the Leaflet, May 2022, Volume 9, Issue 5.