I know that Cyclamen is officially named in Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum, but I am guessing the name’s origin is earlier. Somewhere on the internet, there is a rumor that cave paintings of cyclamen exist, but I have yet to find proof of that. I am planning to do a botanical illustration that draws on historic depictions.

I also could not find evidence for cave paintings, but the name Cyclamen goes back much farther than Linnaeus’s time. It was Latinized from Greek kyklā́mīnos, and that word has ancient origins in the Greek for circle—probably because of the plant’s round tuber. The plant was introduced to cultivation in Western Europe from its native eastern Mediterranean region. There is supposedly a sculpted cyclamen in a house in Pompeii, but it is hard to recognize any of the plant’s distinctive characteristics.

I also could not find evidence for cave paintings, but the name Cyclamen goes back much farther than Linnaeus’s time. It was Latinized from Greek kyklā́mīnos, and that word has ancient origins in the Greek for circle—probably because of the plant’s round tuber. The plant was introduced to cultivation in Western Europe from its native eastern Mediterranean region. There is supposedly a sculpted cyclamen in a house in Pompeii, but it is hard to recognize any of the plant’s distinctive characteristics.

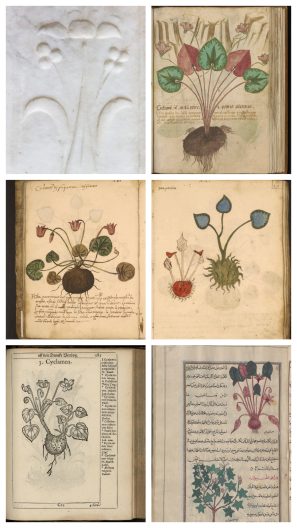

There are pre-Linnaean descriptions of the plant from the time of Greek philosopher Theophrastus (3rd century B.C.E.), and illustrations of it appear in various translations of the Treatise of Plants by Greek physician Dioscorides (who lived in 1st century C.E.).

English herbalist John Gerard wrote about it in 1597: “Sow-Bread is called in Greek Kyklaminos: in Latin, Tuber terræ, and Terræ rapum: of Marcellus, Orbicularis: of Apuleius, Palalia, Rapum porcinum, and Terræ malum: in shops, Cyclamen, Panis porcinus, and Arthanita: in Italian, Pan Porcino: in Spanish, Mazan de Puerco: in High Dutch, Schweinbrot: in Low Dutch Uetkins Brot: in French, Pain de Porceau: in English, Sow-Bread. Pliny calleth the colour of this flower in Latin, Colossinus color: in English, murrey colour.” Cyclamen’s common name ‘sowbread’ suggests the tubers were eaten by pigs.

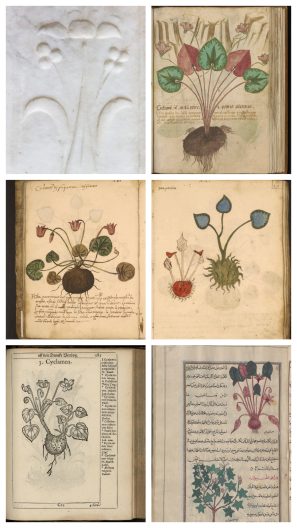

Here are assorted historic depictions of Cyclamen:

- A 19th century printing of an Arabic translation of Dioscorides by Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq al-ʻIbādī (809?-873 C.E.). Note the Arabic name qûqlâmînûs , based on the Greek name.

- From Flora Danica by Simon Paulli (1648)

- This image, Cyclamen Folio Hederic (The Ivy-leaved Cyclamen), comes from Hortus Floridus by Crispijn de Passe II (Utrecht: Officina Calcographica Cr. Passaei, 1614), and the tubers are depicted here.

- Antonio Guarnerino da Padova’s Herbe Pincte (1441) contains an illustration of Cyclamen, and there are two Cyclamen images (images 45 and 46) in an anonymous 15th century Northern Italian herbal, using the ‘sowbread’ common name.

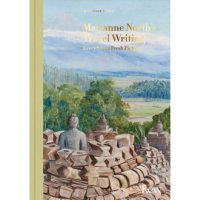

The life and work of Marianne North, the eminent Victorian botanical artist, is well documented. Do we need another book about her? Michelle Payne provides a positive answer in this well-illustrated volume. She aims to modify the dominant image of North as an intrepid lone traveler to the many sites of her art, to show us a different, fuller picture. North always had a cast of helpers around her and benefited from her colonial connections.

The life and work of Marianne North, the eminent Victorian botanical artist, is well documented. Do we need another book about her? Michelle Payne provides a positive answer in this well-illustrated volume. She aims to modify the dominant image of North as an intrepid lone traveler to the many sites of her art, to show us a different, fuller picture. North always had a cast of helpers around her and benefited from her colonial connections.

Between 1871 and 1885 North traveled to 15 countries in Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Americas. The book presents her trips in chronological order, using substantial excerpts from North’s journals. Along with a few examples of the stunning botanical art North is famous for, Payne includes many of North’s impressionistic paintings of landscapes, cities, and buildings she visited, and a few photographs of the journal pages themselves.

The journals record North’s interactions with the many people who hosted her, and her reactions, sometimes amused. Here she describes a formal dinner for fifty in India: “. . . Lady L. herself so hung with artificial flowers that she made quite a crushing sound whenever she sat down” [p. 169].

She also tells of her less comfortable accommodations, this one in Tenerife: “A great barn-like room was given up to me, with heaps of potatoes and corn swept up into the corners of it. I had a stretcher-bed at one end, on which I got a very large allowance of good sleep. The cocks and hens roosted on the beams overhead and I heard my donkey and other beasts munching their food and snoring below” [p.84].

Often she describes plants with the precision one would expect of this woman who painted them so accurately. Here she describes her first view of Sparaxis pendula in South Africa: “Its almost invisible stalks stood four or five feet high, waving in the wind. These were weighed down by strings of lovely pink bells, with yellow calyx, and buds; they followed the winding marsh, and looked like a pink snake in the distance” [p. 217]. Close observation plus context, including a familiar image – very impressive.

Back home in England, North gives the reader an afternoon with Charles Darwin a few months before his death: “He sat on the grass under a shady tree, and talked deliciously on every subject to us all for hours together, or turned over and over again the collection of Australian paintings I brought down for him to see, showing in a few words how much more he knew about the subjects than anyone else, myself included, though I had seen them and he had not” [p. 257].

This reader came away from

Travel Writing wishing she could spend an evening with this brilliant, multitalented woman – just the result Michelle Payne was hoping for.

Reviewed by Priscilla Grundy in the Leaflet, volume 11, issue 8, August 2024

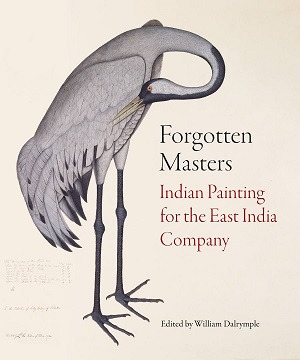

Forgotten Masters (edited by William Dalrymple) focuses on restoring to art history the paintings and the forgotten names of the artists in India who worked for British government officials during the 18th and 19th centuries. Although the text suggests a mostly benevolent relationship between the artists and their patrons, the goal of reclaiming the names of at least some of the artists works to right one colonial wrong.

The book is based on an exhibition of the same title at the Wallace Collection, a museum in a historical house in London, Hertford House. Sir Richard Wallace, the “likely illegitimate son” of the 4th Marquess of Hertford, collected art and left it to his wife, who donated it to the British government (except some she gave her secretary).

Each of the book’s six chapters is accompanied by essays by one or two specialists in Indian art. Of particular interest to Miller Library readers is the section on “Indian Export Art? The botanical drawings,” with an essay by H.J. Nolte. He writes he had more than 7,000 botanical drawings to choose from, in just four British collections, plus many more in private hands. The Indian artists were shown examples of European botanical drawings and instructed to copy them. They were very successful. Nolte makes clear throughout that the paintings retain some qualities of the techniques the artists had learned previously in various Indian locations. One early example, Trapa natans (p. 83), by an unknown artist, shows more of these techniques than others in the book with its two-dimensional presentation and near symmetrical arrangement. Others, such as Spray of Green Mangoes (p.86), by Bhawani Das, and A Cobra Lily (p. 87), by Vishnupersaud, display a crisp, representational style.

The variety of subjects makes this book particularly impressive, all elegant reproductions in the coffee-table-sized book. Paintings of animals and birds, portraits of individuals and groups of both Indians and British, drawings of buildings (including the Taj Mahal) — the book shows many aspects of Indian life at the time. And it is all a delight to look at.

Reviewed by Priscilla Grundy in Leaflet for Scholars, Volume 11, Issue 6, June 2024

Sara Plummer Lemmon (1836-1923) was a transplanted easterner, moving from New York to California in her early 30s hoping to find a climate to improve her health. She settled in Santa Barbara, establishing a library and becoming interested in the native flora.

Sara Plummer Lemmon (1836-1923) was a transplanted easterner, moving from New York to California in her early 30s hoping to find a climate to improve her health. She settled in Santa Barbara, establishing a library and becoming interested in the native flora.

A decade later, she married John Gill (“JG”) Lemmon (1831-1908), a survivor of the notorious Andersonville prison in the Civil War, who had also moved to California for his health. Together they explored the mountains of Arizona, California, and Mexico, developing an important herbarium, now housed at the University of California, Berkeley. Sara was also a skilled botanical illustrator. Her and JG’s story is told in “The Forgotten Botanist” by Wynne Brown.

Sara was an advocate for having the California poppy (Eschscholzia californica) named the state flower. Although first proposed to the state legislature in 1895 and passed by both houses nearly unanimously, two succeeding governors refused to sign the bill for unrelated political reasons, postponing enactment until 1903.

The joint headstone for JG and Sara in Oakland’s Mountain View Cemetery lists them as “partners in botany. Author Brown reflects, “The actual balance of that partnership between JG and the woman known to the world as ‘& wife’ is still—and probably always will be—up for question,” but she concludes that many future ecologists will “rely on the work of this determined couple.”

Excerpted from Brian Thompson’s article in the Winter 2023 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

Phaidon Press is noted for their exquisite art books, capturing in print garden subjects from many different media. “Flower: Exploring the World of Bloom” is the 4,000 year story of human fascination with flowers as told in over 300 images.

Phaidon Press is noted for their exquisite art books, capturing in print garden subjects from many different media. “Flower: Exploring the World of Bloom” is the 4,000 year story of human fascination with flowers as told in over 300 images.

Edited seamlessly by Victoria Clarke, the book begins with an insightful essay by Anna Pavord, the author of “The Tulip” and several other books that examine the human history with plants and landscapes. She does an excellent job of setting the background for the art that follows, noting that “the images in this superb collection could have been arranged by chronology or theme, but instead pictures have been cleverly paired on facing pages to highlight revealing or stimulating similarities or contrasts.”

This book is fun! You can open anywhere and immediately dive into a story told in both prose and images. It’s also huge, a hefty tome worthy of any coffee table. At first glance it might see like a lot of lovely fluff. But read on! It is an excellent and easy-to-digest history book as well as art exhibit.

A stain glass window by Louis Comfort Tiffany of wisteria looking out on Long Island’s Oyster Bay is contrasted on the opposite page with a 17th century Japanese tea pot with overglazed enamel, also depicting wisteria. A 19th century, hand-colored lithograph of a bouquet of peonies is matched with a 2011 watercolor designed to look like an herbarium specimen, also of peonies.

The subjects come from around the world and reflect developing traditions. A 1973 painting using gouache on paper is a recent stylistic example by a member of the Kwoma people of Papua New Guinea, adapting their practice of bark painting formerly used to decorate the ceilings of ceremonial buildings. This is complemented on the opposite page by the image of a bag made with glass beadwork from the last half of the 19th century. Equally colorful as the Kwoma piece, it was created by an anonymous member of the Nēhiyawak peoples of eastern Canada. The use of glass beads reflects incorporation into the native artform a new material after contact with European traders.

The book is nicely supplemented by ending appendices that include a timeline of flowers in human history, the symbolism of flowers, and short biographies of key artists represented. This is a book that takes time to digest, but that is time well spent.

Excerpted from the Summer 2021 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

Emily Carr (1871-1945) was a native of Victoria, British Columbia and lived much of her life in that city. She is best known as a painter, but was also an accomplished writer. Many of her works in both disciplines reflected her passionate interest in the indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island and other parts of British Columbia.

Emily Carr (1871-1945) was a native of Victoria, British Columbia and lived much of her life in that city. She is best known as a painter, but was also an accomplished writer. Many of her works in both disciplines reflected her passionate interest in the indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island and other parts of British Columbia.

She also had a great love for the natural world and would camp out on Vancouver Island in a trailer she named Elephant. While recovering from a stroke, she completed a manuscript in early 1941 about wild flowers, expressing her desire to end her convalescent and experience the rebirth of spring.

Titled “Wild Flowers”, this work was not published until 2006 by the Royal BC Museum. As Carr’s paintings do not feature close-ups, the editor chose to pair her descriptions with the art of Emily Henrietta Woods (1852-1916). An early art teacher of Carr, Woods was noted for her full-size water color illustrations of wild flowers.

Carr has a distinctive way of describing her subjects. This is not a traditional field guide in any way, but reading it will give you a very different appreciation of some of our most familiar plants. She described our native dogwood (Cornus nuttallii) as resembling a “badly cooked flapjack”, Fritillaria affinis as “brown tulips”, while a mock-orange (Philadelphus lewisii) is an “understudy to true orange blossoms.”

Carr also had her own ideas about punctuation, making her plant descriptions especially lyrical. Of our native flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum), she writes: “This bare little bush begins to erupt little bumps all along her wood branches at the first burst of spring every glint of cool sunshine swells the bumps a little more till presently they burst and out squeezes a folded up rosy little tuft of blossom with a sweet, tart smell, very invigorating.”

Excerpted from the Winter 2021 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

Margaret Stones (1920-2018) was born in Australia but spent much of her career in Britain. She was the principal contributing artist to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine from 1958-1981 and illustrated three gardening books by the Scottish plant explorer E. U. M. Cox and his son Peter Cox in the 1950s and 1960s. She is perhaps most famous for illustrating the six-volume “The Endemic Flora of Tasmania” published between 1967 and 1978.

Margaret Stones (1920-2018) was born in Australia but spent much of her career in Britain. She was the principal contributing artist to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine from 1958-1981 and illustrated three gardening books by the Scottish plant explorer E. U. M. Cox and his son Peter Cox in the 1950s and 1960s. She is perhaps most famous for illustrating the six-volume “The Endemic Flora of Tasmania” published between 1967 and 1978.

She came to America for the bicentennial celebration in 1976, when Louisiana State University commissioned her to illustrate the “Native Flora of Louisiana.” This project eventually included 200 watercolors of the native plants and wasn’t completed until 1990. The stunning, folio size, limited edition book of these images only became available in 2018.

Both of these massive endeavors are highlights of the Miller Library’s botanical art book collection, with design and printing qualities much higher than the average flora. These are huge books: “Tasmania” measuring 16” high by 12” wide and “Louisiana” just slightly smaller. This makes the detail and artistry especially vibrant. Stones insisted on drawing from live specimens and would often seek examples in the wild. Other subjects were freshly picked plants flown from their source to her residence near Kew Gardens.

Author Phillip Cribb wrote in her obituary for Curtis’s Botanical Magazine (Volume 36, 2019): “During her life, Margaret fought hard for botanical artists to receive the recognition and recompense that their work demanded. Her contemporaries revered her for her efforts to promote the discipline and the present generation of botanical artists, most who did not know her, have benefited from her determination.”

Excerpted from the Winter 2021 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

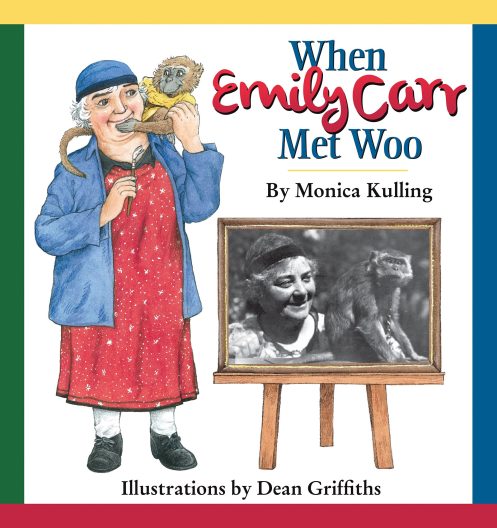

Emily Carr was known for her menagerie of animals. She bred dogs, had several cats, a parrot, and a pet rat, but she is perhaps most remember for the Javanese macaque she found at a Victoria pet shop in 1923. This story is captured in the Youth collection book “When Emily Carr Met Woo” by Monica Kulling and illustrated by Dean Griffiths. While tragedy nearly befell Woo in this story, in life he was a muse for Carr for some 15 years.

Emily Carr was known for her menagerie of animals. She bred dogs, had several cats, a parrot, and a pet rat, but she is perhaps most remember for the Javanese macaque she found at a Victoria pet shop in 1923. This story is captured in the Youth collection book “When Emily Carr Met Woo” by Monica Kulling and illustrated by Dean Griffiths. While tragedy nearly befell Woo in this story, in life he was a muse for Carr for some 15 years.

She named the monkey “Woo” after the sound he made while riding on Carr’s shoulders as she strolled the Victoria harborside, typically pushing an old pram filled with puppies and other pets. This scene is permanently captured in a 2010 sculpture of Carr, Woo, and the dog Billie by Barbara Paterson, sited prominently near the harbor.

Excerpted from the Winter 2021 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

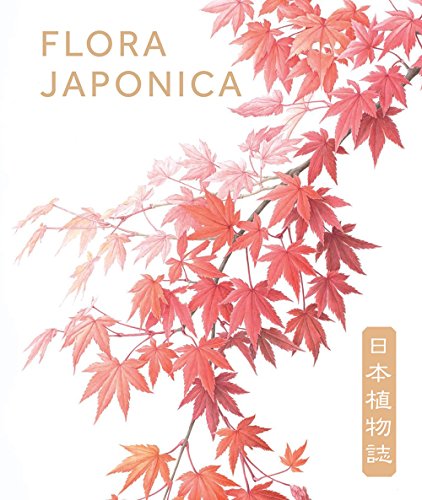

“Flora Japonica,” published by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is really two books in one. The first part provides a rarely documented history of Japanese botany with an emphasis on the literature and illustration of the native flora. The oldest surviving example dates from 1274 and surprisingly was intended to identify plants used by veterinary surgeons. It is considered to be very comparable to European works of the same era.

“Flora Japonica,” published by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is really two books in one. The first part provides a rarely documented history of Japanese botany with an emphasis on the literature and illustration of the native flora. The oldest surviving example dates from 1274 and surprisingly was intended to identify plants used by veterinary surgeons. It is considered to be very comparable to European works of the same era.

Botanical illustration flourished in Edo period (1603-1868), a time when Japan was politically stable and closed to other cultures. This book includes many beautifully reproduced examples of this era, again with many parallels in style to European publications of the same time, despite very limited interaction.

The main part of this book is a celebration of botanical illustration by Japanese artists of today. The nearly one hundred works were originally commissioned for an exhibit presented at Kew, “chosen to represent the unique richness of the Japanese native flora and the influence of Japanese plants on gardens in the West.” These works are beautiful for the artistry, and the extensive notes provide considerable botanical and horticultural background for the subjects.

Excerpted from the Summer 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

One of the earliest fern books, ”The Ferns of Great Britain” (published in 1855), is better known for its illustrator John Edward Sowerby (1825-1870) rather than the botanist who wrote the text, Charles Johnson (1791-1880). While this was not typical, it is perhaps because Sowerby was also the publisher. There is no record of professional jealousy, as the pair produced several other books on wild flowers, poisonous plants, grasses, and useful plants found in Britain and Ireland.

One of the earliest fern books, ”The Ferns of Great Britain” (published in 1855), is better known for its illustrator John Edward Sowerby (1825-1870) rather than the botanist who wrote the text, Charles Johnson (1791-1880). While this was not typical, it is perhaps because Sowerby was also the publisher. There is no record of professional jealousy, as the pair produced several other books on wild flowers, poisonous plants, grasses, and useful plants found in Britain and Ireland.

The Sowerby family included four generations of noted illustrators from the late 1700s to the early 1900s. For this book, John Edward Sowerby created forty-nine, exquisite copperplate engravings and, in a bit of mid-19th century marketing, sold the finished books in three versions. The images could be left uncolored for 6 shillings, be partially hand-colored for 14 shillings, or fully colored for 27 shillings, a range of about $42 to $189 in US dollars today. The Miller Library copy is partially colored, the best of both worlds as it shows both detail and beauty. Johnson’s text was also outstanding, describing Blechnum boreale (now B. spicant or Struthiopteris spicant), the deer fern as “a highly beautiful fern, well worthy of cultivation as an evergreen little liable to injury by frost, and, during the summer presenting an elegant contrast in its varied fronds.”

Excerpted from the Spring 2020 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

I also could not find evidence for cave paintings, but the name Cyclamen goes back much farther than Linnaeus’s time. It was Latinized from Greek kyklā́mīnos, and that word has ancient origins in the Greek for circle—probably because of the plant’s round tuber. The plant was introduced to cultivation in Western Europe from its native eastern Mediterranean region. There is supposedly a sculpted cyclamen in a house in Pompeii, but it is hard to recognize any of the plant’s distinctive characteristics.

I also could not find evidence for cave paintings, but the name Cyclamen goes back much farther than Linnaeus’s time. It was Latinized from Greek kyklā́mīnos, and that word has ancient origins in the Greek for circle—probably because of the plant’s round tuber. The plant was introduced to cultivation in Western Europe from its native eastern Mediterranean region. There is supposedly a sculpted cyclamen in a house in Pompeii, but it is hard to recognize any of the plant’s distinctive characteristics. The life and work of Marianne North, the eminent Victorian botanical artist, is well documented. Do we need another book about her? Michelle Payne provides a positive answer in this well-illustrated volume. She aims to modify the dominant image of North as an intrepid lone traveler to the many sites of her art, to show us a different, fuller picture. North always had a cast of helpers around her and benefited from her colonial connections.

The life and work of Marianne North, the eminent Victorian botanical artist, is well documented. Do we need another book about her? Michelle Payne provides a positive answer in this well-illustrated volume. She aims to modify the dominant image of North as an intrepid lone traveler to the many sites of her art, to show us a different, fuller picture. North always had a cast of helpers around her and benefited from her colonial connections.

Sara Plummer Lemmon (1836-1923) was a transplanted easterner, moving from New York to California in her early 30s hoping to find a climate to improve her health. She settled in Santa Barbara, establishing a library and becoming interested in the native flora.

Sara Plummer Lemmon (1836-1923) was a transplanted easterner, moving from New York to California in her early 30s hoping to find a climate to improve her health. She settled in Santa Barbara, establishing a library and becoming interested in the native flora. Phaidon Press is noted for their exquisite art books, capturing in print garden subjects from many different media. “Flower: Exploring the World of Bloom” is the 4,000 year story of human fascination with flowers as told in over 300 images.

Phaidon Press is noted for their exquisite art books, capturing in print garden subjects from many different media. “Flower: Exploring the World of Bloom” is the 4,000 year story of human fascination with flowers as told in over 300 images. Emily Carr (1871-1945) was a native of Victoria, British Columbia and lived much of her life in that city. She is best known as a painter, but was also an accomplished writer. Many of her works in both disciplines reflected her passionate interest in the indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island and other parts of British Columbia.

Emily Carr (1871-1945) was a native of Victoria, British Columbia and lived much of her life in that city. She is best known as a painter, but was also an accomplished writer. Many of her works in both disciplines reflected her passionate interest in the indigenous peoples of Vancouver Island and other parts of British Columbia. Margaret Stones (1920-2018) was born in Australia but spent much of her career in Britain. She was the principal contributing artist to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine from 1958-1981 and illustrated three gardening books by the Scottish plant explorer E. U. M. Cox and his son Peter Cox in the 1950s and 1960s. She is perhaps most famous for illustrating the six-volume “The Endemic Flora of Tasmania” published between 1967 and 1978.

Margaret Stones (1920-2018) was born in Australia but spent much of her career in Britain. She was the principal contributing artist to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine from 1958-1981 and illustrated three gardening books by the Scottish plant explorer E. U. M. Cox and his son Peter Cox in the 1950s and 1960s. She is perhaps most famous for illustrating the six-volume “The Endemic Flora of Tasmania” published between 1967 and 1978. Emily Carr was known for her menagerie of animals. She bred dogs, had several cats, a parrot, and a pet rat, but she is perhaps most remember for the Javanese macaque she found at a Victoria pet shop in 1923. This story is captured in the Youth collection book “When Emily Carr Met Woo” by Monica Kulling and illustrated by Dean Griffiths. While tragedy nearly befell Woo in this story, in life he was a muse for Carr for some 15 years.

Emily Carr was known for her menagerie of animals. She bred dogs, had several cats, a parrot, and a pet rat, but she is perhaps most remember for the Javanese macaque she found at a Victoria pet shop in 1923. This story is captured in the Youth collection book “When Emily Carr Met Woo” by Monica Kulling and illustrated by Dean Griffiths. While tragedy nearly befell Woo in this story, in life he was a muse for Carr for some 15 years. “Flora Japonica,” published by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is really two books in one. The first part provides a rarely documented history of Japanese botany with an emphasis on the literature and illustration of the native flora. The oldest surviving example dates from 1274 and surprisingly was intended to identify plants used by veterinary surgeons. It is considered to be very comparable to European works of the same era.

“Flora Japonica,” published by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is really two books in one. The first part provides a rarely documented history of Japanese botany with an emphasis on the literature and illustration of the native flora. The oldest surviving example dates from 1274 and surprisingly was intended to identify plants used by veterinary surgeons. It is considered to be very comparable to European works of the same era. One of the earliest fern books, ”The Ferns of Great Britain” (published in 1855), is better known for its illustrator John Edward Sowerby (1825-1870) rather than the botanist who wrote the text, Charles Johnson (1791-1880). While this was not typical, it is perhaps because Sowerby was also the publisher. There is no record of professional jealousy, as the pair produced several other books on wild flowers, poisonous plants, grasses, and useful plants found in Britain and Ireland.

One of the earliest fern books, ”The Ferns of Great Britain” (published in 1855), is better known for its illustrator John Edward Sowerby (1825-1870) rather than the botanist who wrote the text, Charles Johnson (1791-1880). While this was not typical, it is perhaps because Sowerby was also the publisher. There is no record of professional jealousy, as the pair produced several other books on wild flowers, poisonous plants, grasses, and useful plants found in Britain and Ireland.