I know that Cyclamen is officially named in Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum, but I am guessing the name’s origin is earlier. Somewhere on the internet, there is a rumor that cave paintings of cyclamen exist, but I have yet to find proof of that. I am planning to do a botanical illustration that draws on historic depictions.

I also could not find evidence for cave paintings, but the name Cyclamen goes back much farther than Linnaeus’s time. It was Latinized from Greek kyklā́mīnos, and that word has ancient origins in the Greek for circle—probably because of the plant’s round tuber. The plant was introduced to cultivation in Western Europe from its native eastern Mediterranean region. There is supposedly a sculpted cyclamen in a house in Pompeii, but it is hard to recognize any of the plant’s distinctive characteristics.

I also could not find evidence for cave paintings, but the name Cyclamen goes back much farther than Linnaeus’s time. It was Latinized from Greek kyklā́mīnos, and that word has ancient origins in the Greek for circle—probably because of the plant’s round tuber. The plant was introduced to cultivation in Western Europe from its native eastern Mediterranean region. There is supposedly a sculpted cyclamen in a house in Pompeii, but it is hard to recognize any of the plant’s distinctive characteristics.

There are pre-Linnaean descriptions of the plant from the time of Greek philosopher Theophrastus (3rd century B.C.E.), and illustrations of it appear in various translations of the Treatise of Plants by Greek physician Dioscorides (who lived in 1st century C.E.).

English herbalist John Gerard wrote about it in 1597: “Sow-Bread is called in Greek Kyklaminos: in Latin, Tuber terræ, and Terræ rapum: of Marcellus, Orbicularis: of Apuleius, Palalia, Rapum porcinum, and Terræ malum: in shops, Cyclamen, Panis porcinus, and Arthanita: in Italian, Pan Porcino: in Spanish, Mazan de Puerco: in High Dutch, Schweinbrot: in Low Dutch Uetkins Brot: in French, Pain de Porceau: in English, Sow-Bread. Pliny calleth the colour of this flower in Latin, Colossinus color: in English, murrey colour.” Cyclamen’s common name ‘sowbread’ suggests the tubers were eaten by pigs.

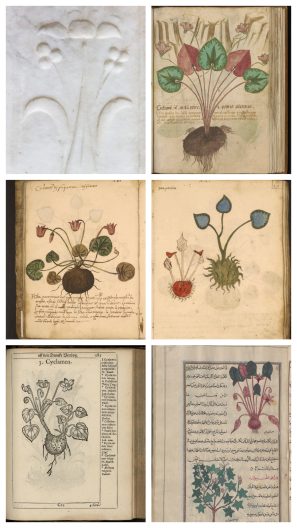

Here are assorted historic depictions of Cyclamen:

- A 19th century printing of an Arabic translation of Dioscorides by Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq al-ʻIbādī (809?-873 C.E.). Note the Arabic name qûqlâmînûs , based on the Greek name.

- From Flora Danica by Simon Paulli (1648)

- This image, Cyclamen Folio Hederic (The Ivy-leaved Cyclamen), comes from Hortus Floridus by Crispijn de Passe II (Utrecht: Officina Calcographica Cr. Passaei, 1614), and the tubers are depicted here.

- Antonio Guarnerino da Padova’s Herbe Pincte (1441) contains an illustration of Cyclamen, and there are two Cyclamen images (images 45 and 46) in an anonymous 15th century Northern Italian herbal, using the ‘sowbread’ common name.

I keep forgetting the name of a plant I added to the garden some time ago, and every year I have to dig through my pile of old plant tags to remind myself. Any mnemonic devices to help me hold Ledebouria cooperi in my head? Any tips on keeping it growing well? How can I propagate it?

I keep forgetting the name of a plant I added to the garden some time ago, and every year I have to dig through my pile of old plant tags to remind myself. Any mnemonic devices to help me hold Ledebouria cooperi in my head? Any tips on keeping it growing well? How can I propagate it?