Emily Dickinson and Charles Darwin shared a passion for the natural world that included close scientific observation and an awe at what they saw that made nature magical. This was true even though neither of them could commit themselves to belief in God or any other supernatural being.

In Natural Magic, Renée Bergland makes the case that Darwin’s writings showed his enchantment with nature, contrary to a public that often read his works as destroying such awe.

Dickinson showed similar enthusiasm for the plants she wrote about. Her work also shows how carefully she examined and described those plants.

In alternating chapters, Bergland has put together parallel biographies. She combines her argument that Darwin included emotional response and Dickinson a scientific one with a history of the changing ideas about the relationship between the sciences and arts in the nineteenth century. In 1780 science and art were all part of one “philosophy.” By 1880 they were separate and at odds with each other.

It is a pleasure to enter into the challenges and relationships of these two towering figures. Regret that the book must come to an end is rare enough for fiction; for this reader it was a first for nonfiction. The book is easy to read – not always true for works built around intellectual history – and full of memorable details.

Darwin, who was enthralled by geology, plants, and animals from childhood, could not find much formal training in science. He suffered from a classical English education which excluded nearly all science, and he hated school. Dickinson, on the other hand, happened to live in a short period of time in America when science was considered essential to girls’ education, and she loved her classes at her Amherst school and her year at Mount Holyoke. She had more formal training in science than he did. He learned it all on his own.

During the nineteenth century science and art were separating. The term “scientist” was first used in the 1830s, replacing “men of science,” since women were excluded. No one, male or female, could earn a living as a scientist. It’s worth noting that both Darwin and Dickinson came from wealthy families, or in Dickinson’s case, wealthy enough, so neither of them needed to work for a salary. Darwin eventually earned handsomely from his books. Dickinson published only a few poems, for no pay.

Sometimes Bergland’s efforts to show parallels in these two lives seem a bit stretched. Still, she is convincing about the connections between their two worlds, and she brings her two subjects very much to life in a time of exciting change.

Review by Priscilla Grundy published in The Leaflet, Volume 12, Issue 1, January 2025.

In

In  The National Herbarium of New South Wales, Australia, acts as setting and springboard for Prudence Gibson’s narratives about and descriptions of preserved plants. Gibson holds in admirable tension the wonders of the herbarium and the troubling colonialism that assumed authority over Australia’s plants, collecting them without permission, naming and organizing them by European standards. The question of who owns plants hovers in the background.

The National Herbarium of New South Wales, Australia, acts as setting and springboard for Prudence Gibson’s narratives about and descriptions of preserved plants. Gibson holds in admirable tension the wonders of the herbarium and the troubling colonialism that assumed authority over Australia’s plants, collecting them without permission, naming and organizing them by European standards. The question of who owns plants hovers in the background.

In the nineteenth century, Canadian women got their hands dirty in lots of botanical projects.

In the nineteenth century, Canadian women got their hands dirty in lots of botanical projects.  “Julia” is a graphic biography of Julia Henshaw (1869-1937), who published the first book on the wild flowers of the Canadian Rockies in 1906. This was a relatively small aspect of her colorful life and author/illustrator Michael Kluckner chose her later role as an ambulance driver in World War I for his book’s cover.

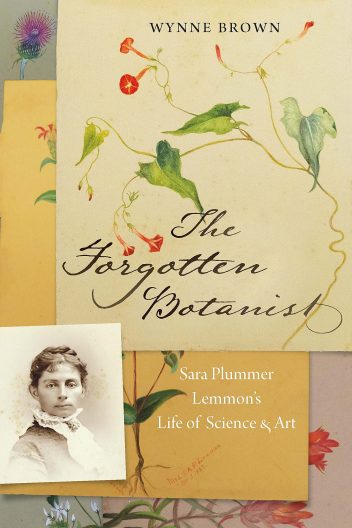

“Julia” is a graphic biography of Julia Henshaw (1869-1937), who published the first book on the wild flowers of the Canadian Rockies in 1906. This was a relatively small aspect of her colorful life and author/illustrator Michael Kluckner chose her later role as an ambulance driver in World War I for his book’s cover. Sara Plummer Lemmon (1836-1923) was a transplanted easterner, moving from New York to California in her early 30s hoping to find a climate to improve her health. She settled in Santa Barbara, establishing a library and becoming interested in the native flora.

Sara Plummer Lemmon (1836-1923) was a transplanted easterner, moving from New York to California in her early 30s hoping to find a climate to improve her health. She settled in Santa Barbara, establishing a library and becoming interested in the native flora. As part of her treatment, her doctor encouraged getting involved in hobbies. She discovered the Sierra Club, and eventually enrolled, at age 51, at the University of California, Berkeley. While not seeking a degree, she took courses on botany, including classes through the California Academy of Science where she met Alice Eastwood. Together, they joined on field botany trips into the mountains of California.

As part of her treatment, her doctor encouraged getting involved in hobbies. She discovered the Sierra Club, and eventually enrolled, at age 51, at the University of California, Berkeley. While not seeking a degree, she took courses on botany, including classes through the California Academy of Science where she met Alice Eastwood. Together, they joined on field botany trips into the mountains of California.