![[The Multifarious Mr. Banks] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/multifariousmrbanks300.jpg)

Joseph Banks was indeed multifarious. Webster defines the term as “having or occurring in great varieties.” Garden lovers might know that Banks became famous after collecting plants on a round-the-world voyage with Captain Cook on the Endeavour in 1768-71, and that he developed and guided Kew Gardens for decades. Toby Musgrave does justice to these huge accomplishments. What he adds is the astonishing range of other ways that Banks influenced the horticultural world – and often other worlds – in late 18th and early 19th century England and beyond.

The book is organized chronologically through the account of Banks’s Endeavour voyage and a smaller one to Iceland, but then proceeds by subject through other areas of Banks’s activities.

Banks was very wealthy. He was endlessly curious. He apparently knew everyone of any importance in England and many others on the Continent and in America. He had an outgoing and friendly personality. James Boswell describes him as “an elephant, quite placid and gentle, allowing you to get upon his back or play with his proboscis,” (p. 187), as opposed to another world traveler (Scottish explorer James Bruce) who was “a tiger that growled whenever you approached him.”

Banks was also a firm believer in progress and in empire (which 21st century readers might be less enthusiastic about). Musgrave shows us Banks’s close relationship with King George III, that nemesis of the American Revolution. “Farmer George,” as the king was called, loved Kew Gardens and walked in it with Banks regularly. In Banks’s decades-long efforts finding new plants and acquiring them for Kew, he remained focused on how plants could be used as crops or resources to aid the empire.

Banks belonged to more that 70 clubs and societies. It’s hard to imagine how he did all this and still managed his own multiple properties, regularly updating them with new planting plans. The most prominent society activity for him was his position as president of the Royal Society, a title he held for 41½ years beginning in 1778. In all these activities Banks assisted other scientists in a multiplicity of areas, giving counsel, offering connections, and sometimes providing cash.

When England needed a new site for prisoners, after Georgia was no longer available due to American independence, Banks weighed in on proposing Botany Bay in Australia as an appropriate location. He also pulled strings and even arranged smuggling a prize breed of Merino sheep from Spain, to the benefit of Australia as well as England.

Through his connections and frequent correspondence with members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham (which included Erasmus Darwin, Benjamin Franklin, and Joseph Priestly), with a great many others, and through his own study, “Banks became an acknowledged expert in a wide range of subjects including agriculture, botanic gardens, canals, cartography, coinage, colonization, currency, drainage, earthquakes, economic botany, exploration, farming, leather tanning, Merino sheep, plant pathology, and even the plucking of geese” (p. 281). Multifarious indeed.

This is a real biography, based on copious research. Musgrave avoids fictional conversations and mostly stays away from suggesting what Banks “must have thought.” Fortunately, the author is not afraid to express an opinion, such as that Banks behaved very badly in breaking his engagement to Harriet Blosset. Mostly the story Musgrave tells is one of amazing positives, ending with his justified assessment of Banks as a “great and remarkable man”(p. 332).

Published in the Leaflet, November 2021, Volume 8, Issue 11.

Jennifer Jewell has gained a wide following for her blog “Cultivating Place.” Produced from her home in northern California, it is self-described as a “conversation on natural history & the human impulse to garden.”

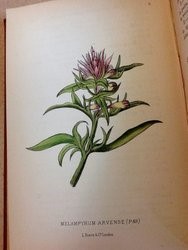

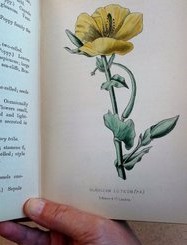

Jennifer Jewell has gained a wide following for her blog “Cultivating Place.” Produced from her home in northern California, it is self-described as a “conversation on natural history & the human impulse to garden.” The Miller Library receives many donations of books each year, and sometimes we open a box and a particular book enchants us. A recent example is a small volume entitled Wild Flowers of the Undercliff, Isle of Wight, published in London in 1881. It is a field guide to a small area of the southern coast of the Isle of Wight, England. The region is prone to landslides and possesses a unique microclimate, as it is protected beneath an escarpment, facing south. The authors, Charlotte O’Brien and C. Parkinson, hoped the book would enable temporary residents of the Undercliff to acquaint themselves with the various plants blooming throughout the year. “As a rule, they are very timid, these ‘wildings of Nature,’ and recede before the advances of man and his bricks and mortar,” and this book seeks to help “seekers after one of the purest of earthly pleasures” [wildflowers] find them.

The Miller Library receives many donations of books each year, and sometimes we open a box and a particular book enchants us. A recent example is a small volume entitled Wild Flowers of the Undercliff, Isle of Wight, published in London in 1881. It is a field guide to a small area of the southern coast of the Isle of Wight, England. The region is prone to landslides and possesses a unique microclimate, as it is protected beneath an escarpment, facing south. The authors, Charlotte O’Brien and C. Parkinson, hoped the book would enable temporary residents of the Undercliff to acquaint themselves with the various plants blooming throughout the year. “As a rule, they are very timid, these ‘wildings of Nature,’ and recede before the advances of man and his bricks and mortar,” and this book seeks to help “seekers after one of the purest of earthly pleasures” [wildflowers] find them. Now that I had birth and death dates and a first name, I used genealogy resources like Ancestry.com and found that Cyril had a sister Marian who lived with him for a time, and she was undoubtedly the illustrator whose signature is in our copy. Census records indicate that she was a woman of “private means,” and this squares with the family’s history as landed gentry with their own coat of arms. At the time of the book’s publication, the 1881 census lists Cyril as a tile manufacturer living with his unmarried sister Marian in Bournemouth, not terribly distant from the Isle of Wight. Their parents were John and Catherine Parkinson of Southwell, Nottinghamshire.

Now that I had birth and death dates and a first name, I used genealogy resources like Ancestry.com and found that Cyril had a sister Marian who lived with him for a time, and she was undoubtedly the illustrator whose signature is in our copy. Census records indicate that she was a woman of “private means,” and this squares with the family’s history as landed gentry with their own coat of arms. At the time of the book’s publication, the 1881 census lists Cyril as a tile manufacturer living with his unmarried sister Marian in Bournemouth, not terribly distant from the Isle of Wight. Their parents were John and Catherine Parkinson of Southwell, Nottinghamshire.