An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children is an innovative book by writer Jamaica Kincaid and artist Kara Walker. Despite the title, it is not for the youngest of readers, and the word ‘colored’ is a pointed, satirical use of an antiquated term. The second half of the title indicates the book’s purpose: An Alphabetary of the Colonized World. In form, the book calls to mind children’s books of centuries past, which were meant as vehicles of moral education. This aim is true here, too, but the content is distinctive for its intense focus on plant discovery and naming in the historical context of conquest, colonial exploitation, and slavery. This book is a necessary counter-narrative to traditional white Eurocentric perspectives on botany and human-plant relationships.

youngest of readers, and the word ‘colored’ is a pointed, satirical use of an antiquated term. The second half of the title indicates the book’s purpose: An Alphabetary of the Colonized World. In form, the book calls to mind children’s books of centuries past, which were meant as vehicles of moral education. This aim is true here, too, but the content is distinctive for its intense focus on plant discovery and naming in the historical context of conquest, colonial exploitation, and slavery. This book is a necessary counter-narrative to traditional white Eurocentric perspectives on botany and human-plant relationships.

Kincaid is known for her literary style and her deep botanical knowledge; Walker is best known for her silhouettes and large art installations that both employ and transform racist imagery of past eras. Though each alphabetical entry is brief, all are dense with layers of meaning. Kincaid’s sentences twist and turn as they disentangle a plant’s context. Here are excerpts from the Amaranth entry:

“When the Spaniards were not committing genocide against the peoples they met, who had made a comfortable life for themselves and created extraordinary, glorious monuments to their civilizations, they were forcing them to abandon this source of physical and spiritual nourishment and replace it with barley wheat, and other European grains. This, along with many other cruelties, led to the decline of the Aztecs and the Inca.” Contemporary gardeners are not immune to a bit of sly critique: “Some gardeners, when reflecting on its [amaranth’s] history and its appearance in their garden as an ornamental, have a very fleeting debate within themselves over the ethics of growing food as an ornamental.”

Walker’s illustrations are thought-provoking: two enslaved Black men laboring under the weight of enormous cotton bolls while, on top of one puff of cotton, a white man in colonial dress takes his ease, smoking a pipe. The illustration accompanying the Guava entry shows a Black woman reaching toward a fruit while poised on a shipping crate marked “Exotic Fruits,” “For Export,” while an impish white boy lifts up the back of her dress. The visual double entendre here speaks volumes.

Though at times veering toward didactic or opaquely allusive language, there is much to learn from this book and its illuminating explorations of plants and their complex histories.

Reviewed by Rebecca Alexander.

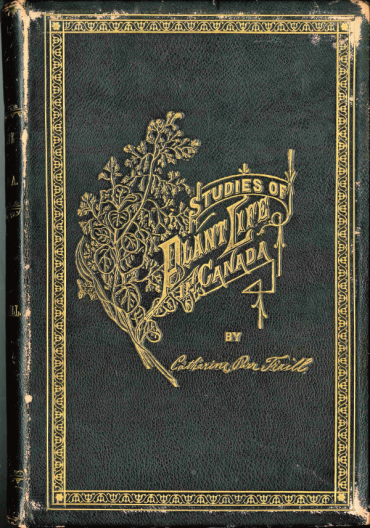

Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899) and Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) were sisters who immigrated to Canada from England in 1832. Both newly married, they were part of a movement of settlers from Britain seeking to escape poverty by moving to Upper Canada (now the province of Ontario), where they hoped to establish a prosperous new home.

Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899) and Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) were sisters who immigrated to Canada from England in 1832. Both newly married, they were part of a movement of settlers from Britain seeking to escape poverty by moving to Upper Canada (now the province of Ontario), where they hoped to establish a prosperous new home.