A long reference article on soil management topics such as fertility, fertilizer, organic matter, manures, compost and how to use soil tests. Published by Washington State University Extension.

Keyword: Compost

Safety of bat guano

My local nursery is selling bags of bat guano, and enriched compost that includes it. What is it good for, and is it safe to use? The company describes all their products as organic.

No matter what is in your compost, it is always a good idea to wear a dust mask when opening bags of soil amendments, and when spreading them in the garden. A mask will help protect you from breathing in airborne fungal spores.

Bat guano is used as a fertilizer, and provides supplemental nitrogen, according to this information from Oregon State University. It contains about 12 percent nitrogen. The ratio of N-P-K (nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium) is approximately 8-5-1.5.

A recent news story on National Public Radio highlighted the human health risks of exposure to bat waste (guano) in caves in Borneo. Both world travelers visiting bat caves and local harvesters of guano may be at risk of contracting very serious viruses, unless they take precautions (masks, gloves, and scrupulous hygiene). In parts of the United States (particularly the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys), there is a fungus called Histoplasma that is found in soil which contains bat or bird droppings. Gardeners who wear masks when digging in affected areas can avoid contracting

histoplasmosis.

Bat and bird guano are allowed as soil amendments “with restrictions” imposed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. They must be decomposed and dried according to the USDA Organic Regulations requirements for raw manure. I recommend contacting the manufacturer of the products and asking them about where they obtain their bat guano, and whether they meet NOP (National Organic Program) and OMRI (Organic Materials Review Institute) standards. You can also ask about their veterinary and phytosanitary certificates for these products, and whether they make certain the guano is harvested sustainably and without harm to the bats and their ecosystem or to the health of harvesters (particularly in countries without strong worker protection laws).

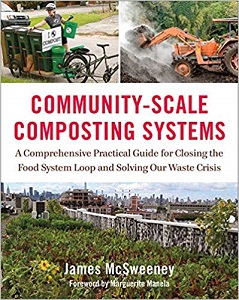

Community-scale composting systems: a comprehensive practical guide for closing the food system loop and solving our waste crisis

Author James McSweeney passionately believes that food scraps are resources — not waste — and has spent a career consulting for farmers, businesses and community based non-profits on how to turn organic material into high quality compost. His experience and knowledge has been collected into a text book that details not only the various techniques for making compost at scale, but also all the economic, logistic and business considerations required for success. The book is very well organized with charts, worksheets for planning, diagrams and excellent color photos. McSweeney’s writing is scientific, but also engaging with just enough anecdotal examples and case studies to keep readers interested in what could be a very dry topic. Footnotes document extensive references, while sidebars give focused information such as “Common regulations for food scrap composters.”

In the introduction McSweeney distills the essence of successful composting to the four Cs: cover, contain, complete and carbon. The following chapters explore several business and system models (such as drop-off, school, commercial, community garden) with economic analysis for each system. The biology and chemistry behind the compost process is detailed in another chapter. Proven composting methods, such as windrows and aerated static pile, are explained the following chapters. Finally the text concludes with chapters on site management and marketing the final product.

This book would be useful for anyone on the composting continuum from serious home scale and multi-family, to neighborhood, school and work place, to on-farm, community gardens and demonstration sites to large scale municipal and industrial enterprises.

Excerpted from the February 2020 Leaflet for Scholars Volume 7, Issue 2.

Disposing of seeds in compost

When is a seed a seed? My wife and I are in agreement on not putting weeds with set seeds in the compost (and the “Easy Compost” book says just that). However, we are less sure about weed flowers (probably OK), and what about seed cases that haven’t formed seeds yet? I’m thinking in particular of foxgloves right now, as the flowers are coming to an end and leaving behind the undeveloped seed cases. I’m unsure whether to compost them or not. Just an aside: our compost pile doesn’t get superheated.

That is a very good question. I found an article in Fine Gardening magazine which discusses harvesting wildflower seeds. It is relevant because it suggests that some unripe seeds may continue to ripen even after being harvested from the plant before maturity. Whether unripe seed will eventually germinate may have to do with the permeability of the seed coat: the more permeable, the more likely the chance it will germinate.

The book Seeds by Peter Loewer (Macmillan, 1995) says that plants with tough seed coats (like legumes and morning glories) “are virtually impermeable to water and must be nicked by the gardener or soaked in warm water for twenty-four hours before they germinate. If these jackets are not broken, scratched, or eroded, water never enters and germination never begins.”

I have found several references to the immature seeds of invasive plants (Ailanthus, teasel, yellow flag iris, to name a few) being capable of germination. The Complete Compost Gardening Guide by Barbara Pleasant and Deborah Martin (Storey, 2008) “weeds that show up in your garden are fair game for compost, even if they are holding seeds. […] Weeds that have not yet begun to bloom and lack viable root buds that help them grow into new weeds can be added to any compost project, but it is important to keep weed seeds to a minimum every chance you get. […] In every climate there are plant criminals known as noxious weeds […] Unless you are confident and committed to processing the compost made from noxious weeds with a high-heat procedure, collect them in a black plastic garbage bag and subject them to various forms of torture before dumping them in an inhospitable place. Cook bags of them in the sun, add water and let them soak into slime, and keep track of what works and what doesn’t. If your superweeds survive your torture methods and you don’t have a spot in your landscape suited to use as a little landfill, discard them as garbage.”

If you want to be on the safe side, avoid putting anything seedy (even green and immature) in the compost, especially if the pile is not going to get especially hot and speed the decomposition process.

on skeletonizing birds

My pet cockatiel died, and I want to know how long it will take to compost the bird in the soil before I can dig up the skeleton and save it.

I am sorry for the loss of your cockatiel. I think that you can either put the body in the compost or find a way to salvage the skeleton, but not both. Bird bones have hollow cavities, and would likely break down quickly in the soil. Some permaculture discussion groups online suggest not burying birds, but instead storing them in the freezer until there are active ant nests, and then leaving them exposed for the ants to clean. I was not sure if this would work, so I consulted Dennis Paulson, Director Emeritus of the Slater Museum of Natural History at University of Puget Sound in Tacoma.

He says that “putting something as small as a cockatiel in the ground isn’t the best idea, as their smaller bones would probably suffer. Putting it near an ant nest might not be much better, as the ants could carry off those small smaller bones. To make a good skeleton, you need to skin the bird and remove a lot of the bigger muscles (in particular, the flight muscles on the breast) as well as the intestines and other organs from the body cavity.” The Slater Museum of Natural History can skeletonize small birds by using their colony of dermestid beetles that eat all the soft tissues, which is the best way to skeletonize something of that size. The museum accepts donations of specimens, but they may also be willing to assist someone who wants to commemorate their pet bird in this way.

In general, dead animals that are not pets and weigh over fifteen pounds must be collected by Seattle Animal Control, but smaller animals that show no signs of disease may be double-bagged and put in the garbage. King County has similar guidelines. Dead wild birds (particularly crows and jays) that may have been affected by West Nile virus should be reported to the Public Health department at 206-205-4394.

using rice straw as compost or mulch

Can rice straw be composted or used as mulch, or is there a risk of it sprouting? I have rice straw wattles that were used for an erosion and stormwater runoff control project which is now complete, and I’d like to use the straw in them.

I checked a couple of our books on grain growing, Homegrown Whole Grains by Sara Pitzer (Storey, 2009) and Small-Scale Grain Raising by Gene Logsdon (Rodale Press, 1977). Both of them refer to using rice straw as a mulch, Logsdon saying it makes an excellent mulch and Pitzer saying it can be left in the field to enrich the soil after the grain is harvested. In general, composting books don’t make any distinction between different types of straw, but caution against the use of hay because it may contain more seeds.

I don’t know which rice wattle product you used in your project, but some of them claim to be weed-free. You would certainly need to liberate the straw from the binding material (plastic netting or geotextile) which gives it its wattle shape before composting or mulching it. Another consideration is the source of the rice straw: if you are gardening organically, you will want to be sure that the rice was not treated with pesticides.

If you are curious about the nutrient balance in rice straw, University of California, Davis’s publication, “Rice Producers’ Guide to Marketing Straw,” October 2010, includes discussion of this issue.

inadequately decomposed materials in compost

I bought compost from the city of Port Angeles and in a sifted wheelbarrow of compost I got three gallons of pencil diameter “twigs”. These are not composted. They break/snap and are green inside. The compost was supposed to be tilled into the garden and flower beds but somewhere in the back of my mind I sort of remember that this will take nitrogen out of the soil to compost down. Is that correct or should I not be concerned?

It sounds like screening your compost was a good place to start; Mike McGrath recommends removing the “odd original ingredient” from compost this way in his Book of Compost (New York, NY : Sterling Pub. Co., 2006). Woody material should definitely be removed, he says. If your compost does not seem otherwise ‘off’ (an ammonia smell, a sulfurous smell, very odd color), sieving off the woody material is often sufficient.

Twigs compost more slowly than other material, and you could, if you like, simply re-compost them, according to the King County Solid Waste Division.

There is some debate over the effects of inadequately decomposed material such as your woody twigs in compost and mulch. Linda Chalker-Scott addresses the question of less-than-fully composted yard waste in her May 2003 myth. She agrees that inadequately decomposed yard waste has a reputation of removing nitrogen from the soil, but writes that the way the yard waste is used affects the way it interacts with the soil. As a mulch (a layer over the soil to prevent weeds or retain moisture), it does not significantly reduce soil nitrogen, but as a compost (incorporated into the soil), it may reduce nitrogen in the soil.

If you are still concerned about the quality of your compost, Stu Campbell suggests using the following techniques on municipal compost in his Mulch It! (Pownal, Vt. : Storey Books, 2001) First, test the pH, and, if it is off, store and turn the compost for several months before using it. Mature compost should have a pH between 6 and 8,

which you can test using a soil test kit or some of the other options listed on Cornell University’s composting pages.

on adding sand and manure to clay soil

We would like to put in a new lawn around a home where there were mostly weeds. The soil is very a heavy silt because it is river bottom land. I have access to free sand; however, I’ve heard conflicting advice regarding adding sand to clay — some say yes, others no. I also have access to a large supply of free horse shavings/manure from a horse stable. Would those shavings be good to add to the soil to help lighten it and add nutrients? I don’t want to go to the expense of bringing in topsoil if I don’t have to. What are your suggestions?

Adding sand to clay soil is not recommended as a way of lightening the soil, as it “may create a concrete-like structure”, according to the booklet Ecologically Sound Lawn Care for the Pacific Northwest by David K.

McDonald. Linda Chalker-Scott addresses the reasons for this in depth in “The Myth of Soil Amendments Part II”.

Instead of adding sand, David McDonald recommends trying to till in compost. At least two inches of compost tilled into the upper six to eight inches of soil is recommended, but four inches tilled into the upper twelve inches is preferable . Try to avoid doing this when the soil is waterlogged, as it may damage the soil structure.

Composting the horse manure and shavings you have access to could be a feasible way to obtain the compost to till into the soil. The Guide to Composting Horse Manure by Jessica Paige of Whatcom County WSU Extension discusses how to compost and use horse manure. She recommends curing such compost at least a few weeks before application, and adds that one to three months is a good, typical composting time in summer or three to six months in winter.

Alternatively, according to David McDonald, if there are a few months of warm weather between autumn and seeding time, you could simply till the fall leaves and grass clippings into your soil. Depending on your planned schedule, this could be very easy. (You can find McDonald’s full booklet “Ecologically Sound Lawn Care for the

Pacific Northwest: Findings from the Scientific Literature and Recommendations from Turf Professionals” online as a very large PDF.)

Another option might be to consider some sort of groundcover if you discoverthat establishing a lawn is an excessively extensive project. Carex species or possibly Juncus phaeocephalus phaeocephalus are more naturally adapted to heavy soils in wet areas than lawn grasses and so may be less work in the end. Though they would not be appropriate for a heavy traffic area, they would be grasslike in structure. Sagina subulata might be more amenable to heavy traffic.

ammonia odor in compost

What does it mean when newly purchased commercial compost smells strongly of ammonia? The compost I’m talking about is 2 yards worth and it has been delivered; I’m stuck with it. Will it improve or hurt the soil I intend to combine with it? And should plants get near it? This is serious. I have obtained all new plants and prepared everything for a new bed…but I’m not going ahead with this because of the amount we’re dealing with.

According to Ann Lovejoy’s October 16, 2003 column from the Seattle PI, a strong ammonia smell indicates “immature” compost that could harm plant roots.

Compost facilities sometimes have bad batches with too much nitrogen in the original mixture of clippings, compared to the amount of carbon, and it can be solved over time by adding “carbon-rich materials such as leaves or [finely ground] wood chips,” according to a compost odor factsheet produced by Resource Recycling Systems, Incorporated. Acidity can also be a factor–less acidic mixtures sometimes remain immature until more acidic ingredients (such as leaves or needles) are added.

If you haven’t already contacted the company, you might try that. At least one local company stands by its compost with a satisfaction guarantee, and that fact may encourage whoever sold you this compost to make things right for you.

information sources about mulching

Can you give me some good sources for information about mulching and different mulching materials?

Below are many links to information about mulch, including several from Pacific Northwest government agencies. Explore these sites for lots of other useful information about gardening! There are also many helpful books on the subject, such as Mulch It! by Stu Campbell (Storey Books, 2001) and the Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s guide, Healthy Soils for Sustainable Gardens edited by Niall Dunne (2009).

There is an excellent introductory article on the Brooklyn Botanical Garden website entitled “How to Use Mulch”.

ABOUT MULCH, types, and uses–Cornell Cooperative Extension (NY)

King County (Washington) Solid Waste Division mulch info

Make the mulch of it!

INFORMATION FROM THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST (generally useful)

—

Saving Water Partnership (Seattle)

—King Conservation District (Washington), manure share program

COMPOSTING COUNCIL OF CANADA:

Compost.org