I came across a reference to the aromatic scent of Devil’s club, and wondered which part of the plant is fragrant, and how it is used.

Despite its daunting common name and repellent species name, the wood of Oplopanax horridus, particularly the inner bark, is said to be sweetly aromatic. According to an article, “Devil’s Club (Oplopanax horridus): An Ethnobotanical Review” from HerbalGram (Spring 2014, Issue 62), the Makah tribe has used an unspecified part of the plant much as one would use talcum powder for infants. This is elaborated upon by Erna Gunther’s Ethnobotany of Western Washington (1973), which says that Green River peoples dry the bark and pulverize it for use as a deodorant.

Other tribes have used an infusion of the bark as a skin wash. Nancy J. Turner’s Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge (2014), mentions that “bathing in a solution of devil’s club is said to make one strong,” and so the plant might be used prior to contests of strength or hunting.

[By coincidence, there is a common perfume ingredient with a very similar name, opopanax, but it is derived neither from Opopanax (in the Apiaceae) nor Oplopanax (in the Araliaceae). Some say its source is the resin of Commiphora guidottii (a plant in the Apiaceae that is native to Ethiopia and Somalia), and goes by the names scented myrrh, bissabol, and habak hadi. Others say it is derived from the flowers of sweet acacia, Vachellia farnesiana (Fabaceae).]

For 15 years, the Elisabeth C. Miller Library has been hosting an exhibit by the Pacific Northwest Botanical Artists every spring. These artists keep alive a tradition of many centuries by creating scientifically accurate portrayals of the flowers, leaves, seeds, and other parts of plants, often with more detail and accuracy than a photograph.

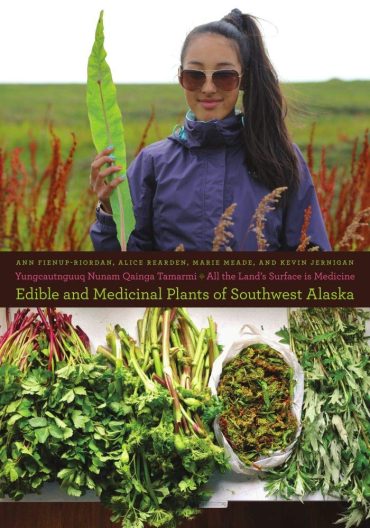

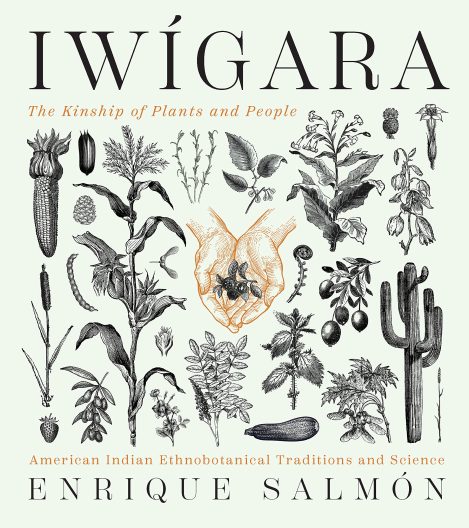

For 15 years, the Elisabeth C. Miller Library has been hosting an exhibit by the Pacific Northwest Botanical Artists every spring. These artists keep alive a tradition of many centuries by creating scientifically accurate portrayals of the flowers, leaves, seeds, and other parts of plants, often with more detail and accuracy than a photograph. The earliest gardeners in North America were not European settlers but the peoples of the indigenous nations, especially in our region. “All native peoples of the West Coast engaged in some form of complex and sophisticated ‘gardening’ of their homelands.”

The earliest gardeners in North America were not European settlers but the peoples of the indigenous nations, especially in our region. “All native peoples of the West Coast engaged in some form of complex and sophisticated ‘gardening’ of their homelands.” If I could only have one book on Scottish plants, it would be “Flora Celtica: Plants and People in Scotland.” While the main title suggests a comprehensive, taxonomic review of natives, authors William Milliken and Sam Bridgewater instead use ethnobotany as their framework to categorize plants by their impact on humans.

If I could only have one book on Scottish plants, it would be “Flora Celtica: Plants and People in Scotland.” While the main title suggests a comprehensive, taxonomic review of natives, authors William Milliken and Sam Bridgewater instead use ethnobotany as their framework to categorize plants by their impact on humans.