I grow many of my own vegetables, but find it harder to get protein. I have corresponded with someone in Washington State who raises escargots, and he mentioned Cornu aspersum was edible, easy to raise, AND invasive. I’ve noticed that there seem to be more snails than slugs as our climate changes.

I would love to volunteer at UW Botanic Gardens and help reduce the snail population. I was on a recent walk and was told that some of the dedicated gardeners come at night with flashlights to find snails, and I would be happy to assist.

Our manager of horticulture says that slug/snail baits are occasionally used as control methods, but there is no such practice as gardeners going out after hours with flashlights seeking slugs and snails in the Arboretum. Your observation about the increasing snail population, and the role of climate change seems to be substantiated. Here is an excerpt from an article in the Everett Herald, which quotes local malacologist David George Gordon: “‘Snails can endure droughts better than slugs because they can pull back into their shells,’ Gordon said. The general warming of the climate, with milder winters, also means there are fewer mass killings during cold snaps.”

The concern when foraging for anything, including invasive snails, is that what you harvest may contain toxic substances. If you want to collect snails, you can try to gather them only from your own garden or a garden you know does not use metaldehyde or iron phosphate-based bait, but even then, they may have been in a landscape nearby and consumed who knows what, including slug bait and poisonous plants.

The USDA APHIS (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service) has guidelines about quarantine of Cornu aspersum and other non-native mollusk species. This includes not breeding them, and not using them in classrooms or nature facilities. Those who want to cultivate escargots have a different perspective. Perhaps Ric Brewer, the article’s author, is the Washington snail farmer you mention. He doesn’t address concerns about snails in an urban setting, and what they may have consumed beyond the borders of one person’s small city garden, which is not a closed system.

A safer and more ecologically sound way to introduce protein sources into your garden would be to grow sunflowers for their seeds, and if you have space, a couple of nut-bearing trees.

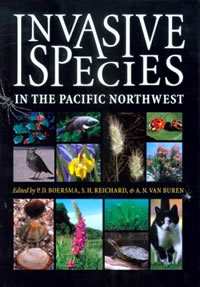

This collaboration of over 80 authors, most of them students at the University of Washington, is a field guide to the region’s invasive species that includes not only the noxious weeds gardeners fear, but aquatic plants, animals, invertebrates and even diseases. Sarah Reichard, head of conservation for UWBG, is one of the three editors that managed the project. The inclusion of the domestic cat is sure to get your attention, but a thorough reading describes a complex ecological web that will influence the way we look at the world around, especially in our gardens. The whole discussion of what constitutes an invasive species is fascinating in itself. A special section on these issues as they pertain to the Haida Gwaii is nice companion reading to the previous book.

This collaboration of over 80 authors, most of them students at the University of Washington, is a field guide to the region’s invasive species that includes not only the noxious weeds gardeners fear, but aquatic plants, animals, invertebrates and even diseases. Sarah Reichard, head of conservation for UWBG, is one of the three editors that managed the project. The inclusion of the domestic cat is sure to get your attention, but a thorough reading describes a complex ecological web that will influence the way we look at the world around, especially in our gardens. The whole discussion of what constitutes an invasive species is fascinating in itself. A special section on these issues as they pertain to the Haida Gwaii is nice companion reading to the previous book.