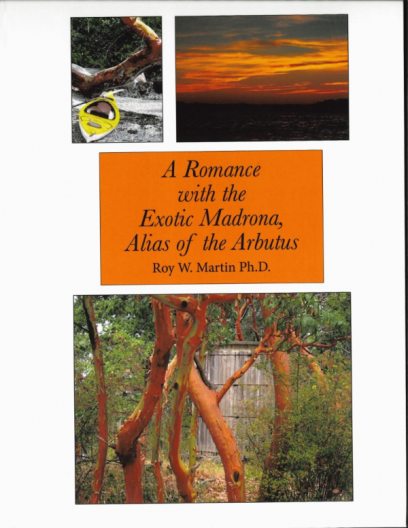

Roy Martin is a retired University of Washington professor of anesthesiology and bioengineering. He is now pursuing a very different passion, the genus Arbutus, best known locally by A. menziesii, the Pacific Madrone. Eleven species are recognized and in “A Romance with the Exotic Madrona, Alias of the Arbutus,” Martin explores them all, visiting their native ranges in Mexico, western North America, and around the Mediterranean.

Roy Martin is a retired University of Washington professor of anesthesiology and bioengineering. He is now pursuing a very different passion, the genus Arbutus, best known locally by A. menziesii, the Pacific Madrone. Eleven species are recognized and in “A Romance with the Exotic Madrona, Alias of the Arbutus,” Martin explores them all, visiting their native ranges in Mexico, western North America, and around the Mediterranean.

This book is very engaging, reading much like a travel journal in places and a history of human culture elsewhere. The author includes a detailed discussion of the common name for our native species, concluding that there are distinction even within our region. In Washington, it is Madrona or Pacific Madrone, while in British Columbia, the name Arbutus is typical.

After exploring the other species, Martin comes home to begin searching for outstanding specimens of A. menziesii. While not abundant, there are several examples of massive trees, hundreds of years old. Martin not only tells the natural history of each tree, as best it is known, but that of the people and locales that surround each.

It is clear that Arbutus menziesii has captured Roy Martin’s heart. “It is not an aggressive tree; it does not, as some trees do, grow rapidly in order to reach the upper stratosphere of the forest and thereby capture most of the available light at the expense of its neighbors. It is, rather, an uncommonly cordial tree, often contorting itself as necessary to find open spaces, through which light falls naturally, as if to accommodate smaller trees it would otherwise effectively starve.”

Excerpted from Brian Thompson’s article in the Spring 2023 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

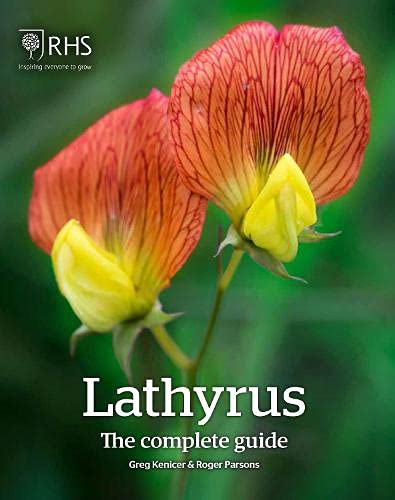

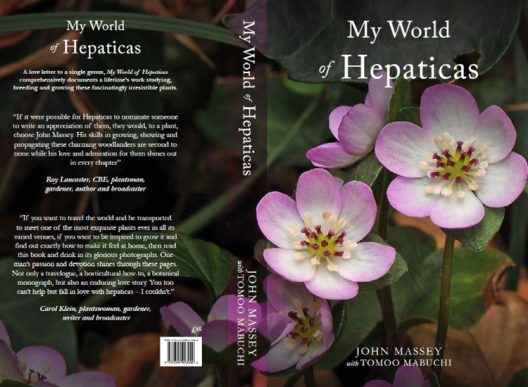

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) has recently been producing excellent single genus books. Known historically as botanical monographs, the works of the past twenty years give equal importance to horticulture. While the many species are considered for their habitats and qualities, so are the many selected varieties or developed cultivars that are important to gardeners. Illustrations are much more prominent than in older books, and include paintings by botanical artists, contemporary and historical, and excellent photography.

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) has recently been producing excellent single genus books. Known historically as botanical monographs, the works of the past twenty years give equal importance to horticulture. While the many species are considered for their habitats and qualities, so are the many selected varieties or developed cultivars that are important to gardeners. Illustrations are much more prominent than in older books, and include paintings by botanical artists, contemporary and historical, and excellent photography. One of the most unusual titles in the Miller Library collection is “A Virgin for Eighty years,” by Linda Eggins, a book about the genus Aucuba, and primarily one species, A. japonica. The reason for the title? It’s complicated.

One of the most unusual titles in the Miller Library collection is “A Virgin for Eighty years,” by Linda Eggins, a book about the genus Aucuba, and primarily one species, A. japonica. The reason for the title? It’s complicated. The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) has recently been producing excellent single genus books. Known historically as botanical monographs, the works of the past twenty years give equal importance to horticulture. While the many species are considered for their habitats and qualities, so are the many selected varieties or developed cultivars that are important to gardeners. Illustrations are much more prominent than in older books, and include paintings by botanical artists, both contemporary and historical, and excellent photography.

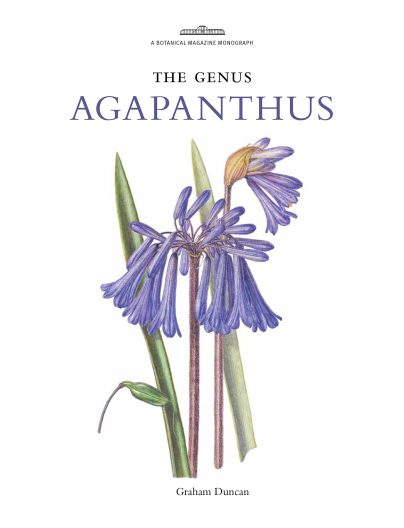

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) has recently been producing excellent single genus books. Known historically as botanical monographs, the works of the past twenty years give equal importance to horticulture. While the many species are considered for their habitats and qualities, so are the many selected varieties or developed cultivars that are important to gardeners. Illustrations are much more prominent than in older books, and include paintings by botanical artists, both contemporary and historical, and excellent photography. The British Royal Botanic Gardens (RBG) has recently been producing excellent single genus books. Known historically as botanical monographs, the works of the past twenty years give equal importance to horticulture. While the many species are considered for their habitats and qualities, so are the many selected varieties or developed cultivars that are important to gardeners. Illustrations are much more prominent than in older books, and include paintings by botanical artists, contemporary and historical, and excellent photography.

The British Royal Botanic Gardens (RBG) has recently been producing excellent single genus books. Known historically as botanical monographs, the works of the past twenty years give equal importance to horticulture. While the many species are considered for their habitats and qualities, so are the many selected varieties or developed cultivars that are important to gardeners. Illustrations are much more prominent than in older books, and include paintings by botanical artists, contemporary and historical, and excellent photography. About 20 years ago, I drove a very narrow roadway in northern Wales in search of Dibley’s Nursery. I had recently discovered the genus Streptocarpus, a houseplant that is closely related to African violets (now considered to be in the same genus). All my reading confirmed that Dibley’s was THE source in Britain, if not the world, for this plant. A visit was mandatory.

About 20 years ago, I drove a very narrow roadway in northern Wales in search of Dibley’s Nursery. I had recently discovered the genus Streptocarpus, a houseplant that is closely related to African violets (now considered to be in the same genus). All my reading confirmed that Dibley’s was THE source in Britain, if not the world, for this plant. A visit was mandatory.

“Just imagine it: your parents on their hands and knees groping at a swarm of crickets unleashed from an upturned box; your teenage sister screaming at toads spawning in the bath; squirting cucumbers launching a raid of missiles down the stairs; and the gut-wrenching stench of a freshly unfurled dragon arum wafting through the front door. This is what I subjected my family to.” (p. 7)

“Just imagine it: your parents on their hands and knees groping at a swarm of crickets unleashed from an upturned box; your teenage sister screaming at toads spawning in the bath; squirting cucumbers launching a raid of missiles down the stairs; and the gut-wrenching stench of a freshly unfurled dragon arum wafting through the front door. This is what I subjected my family to.” (p. 7)