This year is my first in a house with a yard. I’m very

excited to try my hand at growing some food this year. Many of my seed packets say to plant after the last frost or when the soil reaches certain temperatures. Having never planted anything at the beginning of a season before, I

have no idea when any of these temperatures happen around here! Can someone give me some temperatures and approximate times when they are normally reached?

The last frost date in Seattle can be as early as

March 22, but to be on the safe side, April 15-20 would be more

definitive. This information(now archived) can also be found on the web site of local

gardening expert, Ed Hume. The web site also provides further details. Excerpt:

“The last frost date for an area is the last day in the spring that you could have a frost. The average last frost day is the date on which in half of the previous years the last frost had already occurred (so about half of the time it will not frost again and it will be safe to plant tender plants). Most planting directions are based on the average last frost date. The calendar based directions I give (Now it is time to… etc.) are usually based on an average last frost date of April 1st.

An important thing to realize about last frost dates is that the actual date of the last frost is different every year. It can be much earlier than the average or much later. This is especially important for tender plants that can be killed by a frost. For hardier plants, the average last frost date is more an indicator of general growing conditions than a danger sign.”

The closer to the water the garden is, the milder the temperatures.

The moderating effect of Puget Sound or Lake Washington, for instance,

which results in milder winter temperatures, extends inland for some

distance. If your garden is more than a mile or so from water, that

moderating influence could vary. The last frost date for Vashon Island is

April 5; for the Sea-Tac area, April 9. Again, add at least a week and

check your own garden temperatures and patterns.

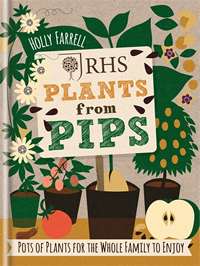

Working in the kitchen, have you ever wondered whether you could grow peppers from pepper seeds? How about a mango tree from a mango pit? This book for gardeners of all ages explains how to germinate a wide range of commonly-seen seeds most people would usually toss in the bin. The entries detail what each plant would need to grow on to maturity, while an illustrated section at the end highlights basic gardening techniques as well as common problems and solutions.

Working in the kitchen, have you ever wondered whether you could grow peppers from pepper seeds? How about a mango tree from a mango pit? This book for gardeners of all ages explains how to germinate a wide range of commonly-seen seeds most people would usually toss in the bin. The entries detail what each plant would need to grow on to maturity, while an illustrated section at the end highlights basic gardening techniques as well as common problems and solutions.