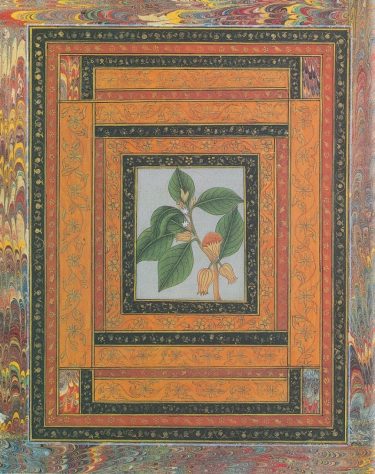

My Strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo) is 8 years old, and very lovely, but the hummingbirds and bees don’t seem to find it. The tree has had some blossoms over the years, but only 1 “strawberry.” Now it has many blossoms. Can I help it by hand-pollinating?

I first saw Arbutus unedo growing in Greece while on a Christmas holiday hiking trip. So I returned home with the dream of a real live tree, self- decorated with red, yellow and orange baubles! My tree is lovely and green as I look out the window, but I may need to hang the decorations. Should I be out there now with a paintbrush and hope for strawberries next Christmas?

There are several factors that affect the fruiting of Arbutus unedo. You don’t mention a cultivar name, so I’m assuming that your plant is the species, Arbutus unedo, which is usually propagated from seeds. Seedling plants are variable, unlike cultivars, which are grown from cuttings (hence, genetic clones). It’s likely that some seed-grown plants do not fruit reliably. An Australian article notes that “vegetatively propagated plants will fruit faster and more predictably than seedlings.”

Another factor is that the flowers and ripened fruits appear on the plant at the same time. Your plant has flowered sparsely until this year, so it’s possible that fruit will form in the next several months, ripening next fall.

The University of Washington Botanic Gardens blog has an entry about this plant: “The flowers are in clusters of tiny white bells (similar to its related genera Arctostaphylos, Pieris, and Enkianthus) and are present October to December while the 1” round fruits of the previous year’s pollination are ripening on the tree. The fruits take 10-12 months to ripen; from green in the spring they begin to turn yellow then orange through summer then ripen to a bright red from October to December at which time they are edible.”

Local non-profit Great Plant Picks indicates that a protected location is also a factor: “Foliage and flowers may be damaged in unusually cold winters, but it will recover in the spring. Plants in protected locations are more reliable fruit producers.” Other sources stress the need for a warm, relatively sunny location. Unfortunately, strawberry tree doesn’t transplant well, so if yours is planted in a shady location, transplanting it is probably not an option.

Even though Arbutus unedo is self-fertile, fruiting is greatly improved by planting more than one tree. On my own walks in Seattle parks, I’ve noticed that strawberry trees planted in groups of two or more seem to fruit prolifically.

Strawberry tree is attractive to many forms of wildlife but is pollinated by bees. If your garden lacks other plants that attract bees, I recommend adding bee-pollinated shrubs, perennials and/or annuals that flower earlier in the year to increase the chances that bees will remain there in fall.

Finally, does your site have what Arbutus unedo needs to grow well, remain healthy, and develop fruit? “This versatile shrub tolerates a wide variety of soil conditions including sand and clay, but it must have a well-drained location.” (Great Plant Picks). It’s drought tolerant when established but may be damaged if not given supplemental water during the very hot and dry conditions the Pacific Northwest has experienced, especially in the last several years. Even using a high nitrogen fertilizer will affect fruiting, promoting leaf and stem growth instead of flowers and fruit.

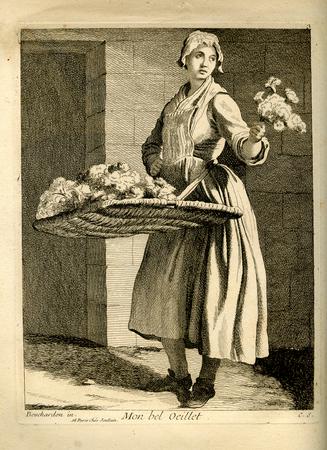

I could not find any information about a beverage of that name, which may be the author’s invention. As long as the plants are grown without chemical fertilizers or pesticides, it should be safe to use spicy, clove-flavored Dianthus petals in drinks and edible concoctions, from cake and salad decoration to flavoring oils and vinegars. According to

I could not find any information about a beverage of that name, which may be the author’s invention. As long as the plants are grown without chemical fertilizers or pesticides, it should be safe to use spicy, clove-flavored Dianthus petals in drinks and edible concoctions, from cake and salad decoration to flavoring oils and vinegars. According to