If you’re new to container gardening, especially edible gardens, start with this book. Maggie Stuckey clearly had a mission in mind when writing this book: to invite people to explore how they can start growing tasty food and to provide them with a resource that is useful, easy to follow, and clearly written.

The crux of The Container Victory Garden is an introduction to taking advantage of small spaces—balconies, patios, or a few steps—and reimaging those spaces as gardens where you can grow and harvest food you like. Stuckey does not assume prior knowledge, gently walking readers through the necessities for container gardens: considering sun and water supply; tools that are especially useful; and advantages and disadvantages to different kinds of containers. She even includes some creative inspiration for reusing furniture or thrift goods to create a container garden that has more personality or better function. She goes through the process of figuring out what kinds of plants to grow with several whole chapters digging more substantially into what’s helpful to know about carrots or tomatoes or basil or pansies.

Janice Minjin Yang and Lee Johnston have also done an excellent job using art to increase the book’s impact. There are three kinds of art used in the book. The first kind is photographs that show readers what the plants look like. The second kind is black-and-white line sketches that illustrate concepts and ideas, making it easier to understand different trellis options or what a root ball looks like. The third kind is paintings depicting scenes of people enjoying their container gardens. I particularly enjoy the last because the paintings help show a wide array of styles when it comes to setting up container gardens and they make it easier for a reader to envision what they might want their garden to be like.

Woven throughout this book are threads about the history of victory gardens. Common during times of war or pandemic, victory gardens have come to occupy a strong space in our cultural imagination for the idea that we can do something to take care of us and those around us in times of profound stress by growing our own tasty, healthy food. As a historian of food and cultural ideas about what we eat, I really enjoyed these threads in Stuckey’s book. She includes historical information, documents and photographs, and recollections from about 20 individuals about their experiences with victory gardens. I feel this dimension of the book helps support the mission of inviting new people into the world of gardening by showing them how they can be part of this bigger, fascinating picture.

While this book is substantial and very helpful, it is not intended to be comprehensive. For readers wanting a more comprehensive book on container gardening, I couldn’t do better than to recommend McGee & Stuckey’s The Bountiful Container, by Rose Marie Nichols McGee and Maggie Stuckey. But for an introductory book on the subject, Stuckey’s The Container Victory Garden is definitely top-notch.

Reviewed by Nick Williams in The Leaflet, Volume 10, Issue 9, September 2023

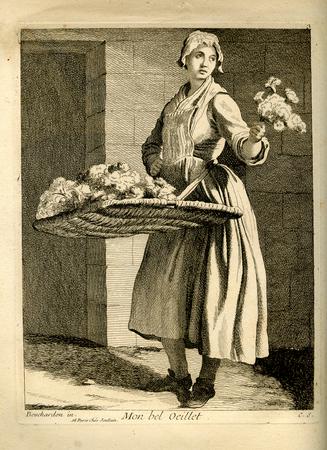

I could not find any information about a beverage of that name, which may be the author’s invention. As long as the plants are grown without chemical fertilizers or pesticides, it should be safe to use spicy, clove-flavored Dianthus petals in drinks and edible concoctions, from cake and salad decoration to flavoring oils and vinegars. According to

I could not find any information about a beverage of that name, which may be the author’s invention. As long as the plants are grown without chemical fertilizers or pesticides, it should be safe to use spicy, clove-flavored Dianthus petals in drinks and edible concoctions, from cake and salad decoration to flavoring oils and vinegars. According to

![[The Food Explorer] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/foodexplorer300.jpg)