|

|||||||||

|

Research Feature Stories: Other News: |

Bacterium Coexists with Humans

Until recently, Chamberlain lived and worked in the Midwest. Recruited to the UW faculty last year, Chamberlain was attracted by the UW’s interdisciplinary environment.

Researchers at the UW Genome Center helped map the genetic code of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Scientists are interested in P. aeruginosa’s extraordinary rate of adaptation as well as its increasing prevalence in chronic and fatal lung infections.

Pseudomonas, likened to a bacterial cockroach, has capitalized on modern life to coexist with humans. Pseudomonas infections were relatively undocumented until the latter half of the 20th century. At that time disinfectants and a higher standard of hygiene worked against many bacteria. Most disinfectants are not effective in getting rid of this bacterium. Preliminary studies suggest that P. aeruginosa has a high number of genes playing a role in its ability to adapt and survive in many different environments.

“Pseudomonas bacteria are tough organisms that are not intrinsically human pathogens,” said Dr. Maynard Olson, principal investigator for the Pseudomonas Genome Project and director of the UW Genome Center. “Pseudomonas bacteria grow much better than most other bacteria and can also live in a huge variety of natural habitats. They metabolize plastics and biodegradable synthetics much better than other bacteria. One of the strains that we’re working with was isolated by microbial ecologists who were monitoring microorganism repopulating waterways after the eruption of Mount St. Helens.”

|

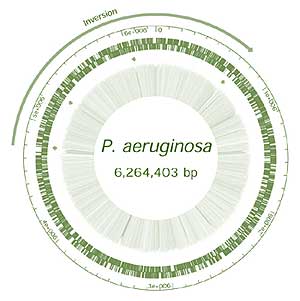

Circular representation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome. Scientists at the UW Genome Center helped map the genetic code of P. aeruginosa, the most common cause of cystic fibrosis. |

P. aeruginosa is the most common cause of chronic, fatal lung infections in the genetic disease cystic fibrosis. These ubiquitous bacteria thrive in the moist environment of the lungs. An immediate goal of UW research is to learn how the bacteria differ from patient to patient and, over time, in a particular patient. During lung infections, P. aeruginosa forms a protective outer layer to shield itself from antibiotics and the body’s natural defenses. Improved understanding of this shielding may lead to new therapies for the infections.

The Pseudomonas Genome Project began in 1997 and was jointly funded by the non-profit Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and Chiron Corporation (formerly known as PathoGenesis, a Seattle-based biopharmaceutical company). Two years later the P. aeruginosa genome had been sequenced. Using standard DNA technology, the group collected 100,000 random samples of sequence and pieced it together.

“At the beginning of the Pseudomonas project, the major difficulty was resolving discrepancies in the data in order to produce a high-quality sequence,” said Olson. “But by the end of the project, that had shifted dramatically in the entire field. Now we are able to concentrate on analyzing the sequence and extracting the biological lessons.”

The researchers found that P. aeruginosa has 6.3 million base pairs with more than 5,500 genes, many of which are potential targets for drug therapy. Their findings were published in the Aug. 31, 2000, issue of Nature, and the genetic data are posted on-line. Scientists around the world have been able to access these data and make free, unrestricted use of them since early in the project.

|

| UW AMC Medical Center | UW School of Medicine | Harborview | UW MC | Search UW AMC | UW Home | Contact Us | ©2001-2002, University of Washington Academic Medical Center. All rights reserved. Please honor our copyrights. |

|