Helen Fowler O’Gorman (1904-1984) grew up in Wisconsin but graduated in fine arts and architecture from the University of Washington. She began her career as sculptor and went to Mexico in 1940 to continue her studies with painter Diego Rivera. He encouraged her to concentrate on painting and over the next two decades, she developed a passion for illustrating the native and garden plants of her adopted country, leading to the publication of “Mexican Flowering Trees and Plants” in 1961.

At the time of their meeting, Rivera was married to painter Frida Kahlo. Together, they lived in a house designed by the Irish-Mexican architect (and painter) Juan O’Gorman, Helen’s future husband. Together, the O’Gormans designed and built Casa Cueva, their home and landscape that partially encompassed a natural cave.

Helen O’Gorman’s book demonstrates not only her skill as a painter, but in the text her knowledge of Mexican botany and horticulture. She was particularly interested in the gardening heritage of the Aztecs and other pre-Hispanic peoples. “Innumerable plants were sacred to the Aztecs and certain flowers were set aside by the priests for religious rituals.”

While she includes the ethnobotanical uses of plants for food, medicines, and dyes, she emphasizes the passion these civilizations had to grow flowers for ornamental purposes and as perfumes. The latter use was considered especially important for reducing fatigue or providing a mild stimulant. This practice was picked up by the conquering Spanish, a fact O’Gorman discovered in a surviving administration document on the “treatment of the weary office holder of the 16th Century.”

The author regards this book as an attempt to introduce “the most noticeable flowering plants” to her readers. Most are natives, while a few are popular introductions. Each entry includes some botanically distinguishing features, but this is less a field guide and more an invitation to share the appreciation and various uses of these plants across the breadth of Mexico.

For example, most species of cosmos are native to Mexico. Referring to our common garden cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus), she describes: “In the state of Michoacán one sees a breathtaking sight: solid pink fields of them, often bordered with the yellow of wild mustard.” She also highlights how a decoction of another species found in North American gardens, C. sulphureus, “is employed to fight the effects of the sting of the scorpion” with small cup given the sting victim every hour.

Excerpted from the Winter 2021 issue of the Arboretum Bulletin

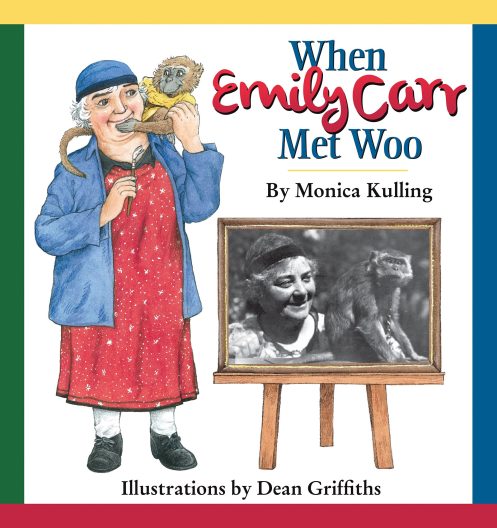

Emily Carr was known for her menagerie of animals. She bred dogs, had several cats, a parrot, and a pet rat, but she is perhaps most remember for the Javanese macaque she found at a Victoria pet shop in 1923. This story is captured in the Youth collection book “When Emily Carr Met Woo” by Monica Kulling and illustrated by Dean Griffiths. While tragedy nearly befell Woo in this story, in life he was a muse for Carr for some 15 years.

Emily Carr was known for her menagerie of animals. She bred dogs, had several cats, a parrot, and a pet rat, but she is perhaps most remember for the Javanese macaque she found at a Victoria pet shop in 1923. This story is captured in the Youth collection book “When Emily Carr Met Woo” by Monica Kulling and illustrated by Dean Griffiths. While tragedy nearly befell Woo in this story, in life he was a muse for Carr for some 15 years.![[book title] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/bloomingflowers284.jpg)

![[Spirit of Place] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/spiritofplacethemakingofaNewEnglandgarden300.jpg)

![[Just the Tonic] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/justhetonic.jpg)

The October 2020 Northwest Horticultural Society Symposium, Gardening for the Future: Diversity and Ecology in the Urban Landscape, helped raise my awareness of the complex and wide-ranging network, both human and natural, that foster the creation of our gardens. Several recent books have helped me in that learning process, too.

The October 2020 Northwest Horticultural Society Symposium, Gardening for the Future: Diversity and Ecology in the Urban Landscape, helped raise my awareness of the complex and wide-ranging network, both human and natural, that foster the creation of our gardens. Several recent books have helped me in that learning process, too.![[Wild Child] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/wildchild300.jpg)

![[The Scentual Garden] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/thescentualgarden.jpg)

![[Corn: A Global History] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/Cornaglobalhistory.jpg)

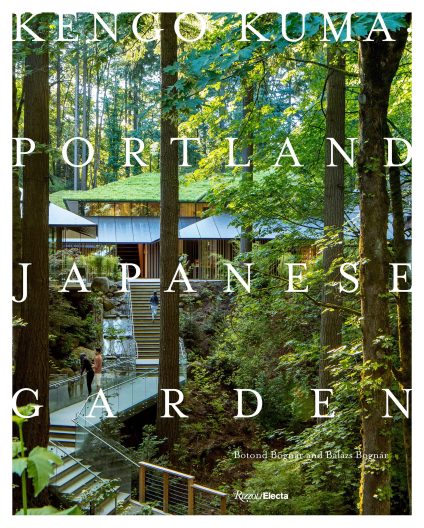

I recently visited the Portland Japanese Garden after many years away, taking a tour in June 2019 as part of a Hardy Plant Society of Oregon study weekend. The focus was the new part of the garden, the Cultural Village, which opened in 2017, but I also made time to explore the earlier areas that date from 1967.

I recently visited the Portland Japanese Garden after many years away, taking a tour in June 2019 as part of a Hardy Plant Society of Oregon study weekend. The focus was the new part of the garden, the Cultural Village, which opened in 2017, but I also made time to explore the earlier areas that date from 1967.