![[Oh, La La!] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/Ohlala!.jpg)

“I am a storyteller.”

Ciscoe Morris is an expert gardener, eager to share his knowledge with those at all levels of gardening ability. But this self-assessment from the introduction of his new book is also very accurate. He grew up in a large family of storytellers and that skill came first. Later, gardening became the framework for his tales.

“Oh, La La!” is a fine collection of short essays, each no more than a few pages. You can open the book anywhere and immediately be engaged, no matter the topic. Later, you’ll realize how much you learned.

There are three main settings: his home garden, the Seattle University campus where he worked for many years, and the many locations from his travels. While the plants take center stage, the interactions of the gardener with other people and with animals – especially beloved dogs – are the memorable highlights.

I have several favorite stories. One of the longer chapters lays out the many – usually unsuccessful – ways to control moles, concluding, “if nothing else works, you can learn to live with moles.” Another lesson confirms my personal experience with the Colorado blue spruce (Picea pungens var. glauca). It belongs in Colorado, safe from the spruce aphids that devastate this species in our mild, maritime climate.

Ciscoe promises this is not his last book. “I already have an idea for the next one. Oh, la la: I can’t wait to get started!” I can hardly wait to read it.

![[The Outdoor Classroom in Practice, Ages 3-7] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/outdoorclassroominpractice.jpg)

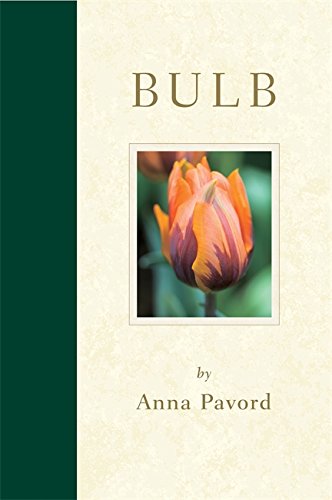

For pure opulence, nothing matches Anna Pavord’s “Bulb”, a compilation of the author’s favorites of primarily spring-flowering selections. Each is described with such heartfelt devotion that you know they must be good. She includes some newer varieties but the treasures are the older, time-tested names that just keep giving every year.

For pure opulence, nothing matches Anna Pavord’s “Bulb”, a compilation of the author’s favorites of primarily spring-flowering selections. Each is described with such heartfelt devotion that you know they must be good. She includes some newer varieties but the treasures are the older, time-tested names that just keep giving every year.![[Landmarks] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/landmarks.jpg)

One of the earliest fern books, ”The Ferns of Great Britain” (published in 1855), is better known for its illustrator John Edward Sowerby (1825-1870) rather than the botanist who wrote the text, Charles Johnson (1791-1880). While this was not typical, it is perhaps because Sowerby was also the publisher. There is no record of professional jealousy, as the pair produced several other books on wild flowers, poisonous plants, grasses, and useful plants found in Britain and Ireland.

One of the earliest fern books, ”The Ferns of Great Britain” (published in 1855), is better known for its illustrator John Edward Sowerby (1825-1870) rather than the botanist who wrote the text, Charles Johnson (1791-1880). While this was not typical, it is perhaps because Sowerby was also the publisher. There is no record of professional jealousy, as the pair produced several other books on wild flowers, poisonous plants, grasses, and useful plants found in Britain and Ireland. While the Victorian fern craze of late 19th century Britain had less impact in North America, one noted author who recognized the need for a guide to the ferns of the northeastern United States was Frances Theodora Parsons (1861-1952), who wrote the field guide “How to Know the Ferns” (1899). Parsons was very active in New York City and State politics and active advocate for women’s suffrage. Her autobiography, written late in her long life, talked little of her botanical writing that included three other books. However, during her active botany period, before the death of her second husband in 1902, her books were very popular.

While the Victorian fern craze of late 19th century Britain had less impact in North America, one noted author who recognized the need for a guide to the ferns of the northeastern United States was Frances Theodora Parsons (1861-1952), who wrote the field guide “How to Know the Ferns” (1899). Parsons was very active in New York City and State politics and active advocate for women’s suffrage. Her autobiography, written late in her long life, talked little of her botanical writing that included three other books. However, during her active botany period, before the death of her second husband in 1902, her books were very popular. Edward Joseph Lowe (1825-1900) had the financial means to be an astronomer, a meteorologist, and an expert on ferns, the latter for him being “a matter of everyday life.” He wrote several very popular books in the last half of the 19th century, during the “fern craze” that engulfed England at the time. In “Our Native Ferns” (1867-69), he focuses on many of the highly coveted mutations, including Athyrium filix-femina var. multifidum, which he describes as “a most beautiful, symmetrical, and graceful Fern, although a monstrosity.” This book was a catalogue to these many forms, which were the most desirable objects for fern collectors.

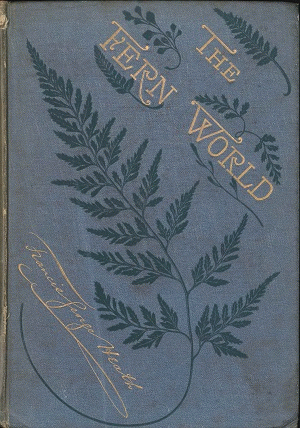

Edward Joseph Lowe (1825-1900) had the financial means to be an astronomer, a meteorologist, and an expert on ferns, the latter for him being “a matter of everyday life.” He wrote several very popular books in the last half of the 19th century, during the “fern craze” that engulfed England at the time. In “Our Native Ferns” (1867-69), he focuses on many of the highly coveted mutations, including Athyrium filix-femina var. multifidum, which he describes as “a most beautiful, symmetrical, and graceful Fern, although a monstrosity.” This book was a catalogue to these many forms, which were the most desirable objects for fern collectors. One of my favorite fern authors is Francis George Heath (1843-1913). A prolific writer, he was keen on popularizing ferns with a well-honed eye and wit. He wrote at least one book about ferns for children and in all his books, he encourages fern tourism. His favorite destination was his home shire of Devon, located in the west of England with long, wild coasts on both the English and Bristol Channels.

One of my favorite fern authors is Francis George Heath (1843-1913). A prolific writer, he was keen on popularizing ferns with a well-honed eye and wit. He wrote at least one book about ferns for children and in all his books, he encourages fern tourism. His favorite destination was his home shire of Devon, located in the west of England with long, wild coasts on both the English and Bristol Channels.