What can you tell me about asafetida? I know it is used in cooking (especially in India), but is it used medicinally?

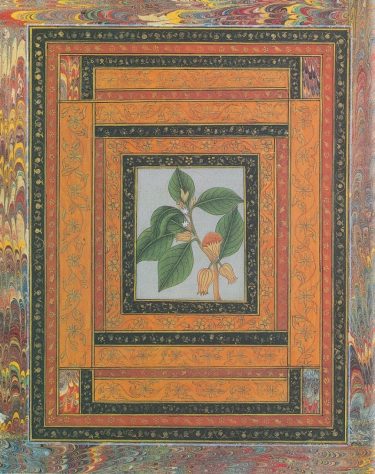

The plant source of asafetida is Ferula assa-foetida, a perennial in the Apiaceae (carrot) family. As you mention, it is used in cooking, primarily the cooked leaves and shoots, but also the sap or gum which is extracted from the plant’s roots and dried as resin or pulverized into powder. It has a very pungent sulfurous odor, especially in resin form. In Africa, Ferula was a substitute for Silphium, whose extinction was recorded by Pliny the Elder in 77 C.E.

The plant resin is also used medicinally in other parts of the world, including the Middle East and Europe. Around the world, it has an array of common names, many of them variants on devil’s excrement, due to the odor.

According to Judith Taylor’s Plants in the Civil War, asafetida came to America with enslaved Africans who had multiple medicinal, magical, and apotropaic (protective, warding off evil) uses for it. Among enslaved people in this country, there was a tradition of wearing a red flannel bag containing the plant’s roots and additives like red pepper, sassafras, and snakeroot. Colin Fitzgerald’s “African American Slave Medicine of the 19th Century” (Bridgewater State University Undergraduate Review, 12, 44-50, 2016) goes into greater depth. Here is an excerpt:

“Victoria Adams, of Columbia, South Carolina, recalls using the plant as a preventive measure against diseases on her plantation,'[w]e dipped asafetida in turpentine and hung it ‘round our necks to keep off disease’ (Slave Narratives). Asafetida was used as preventative against a number of pulmonary diseases such as whooping cough, bronchitis, small pox, and influenza. It was usually placed in a bag around someone’s neck so that they could breathe in the fumes. Asafetida is found to have worked as an anti-flatulent by reducing the amount of indigenous microflora in the gut. Because of its close relation with the famed silphium of Cyrene (belonging to the same family, ferula), it has also been reported to contain naturally occurring organic contraceptive compounds.”