Longshoremen loading oyster shells 1927 Tacoma

In the early twentieth century, loading and unloading ships was an arduous, labor-intensive process. (Photo Ronald Magden collection)

This essay is presented in three parts.

Click to move to any section:

Part 1: Longshoremen and the Waterfront Before 1934

Part 2: The Start of the Great 1934 Longshore Strike

Part 3: War on the Docks

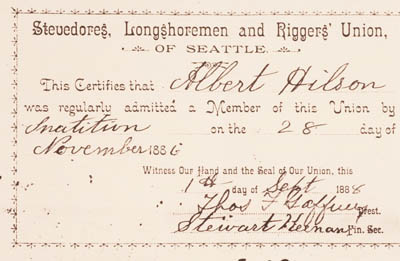

1886 membership card

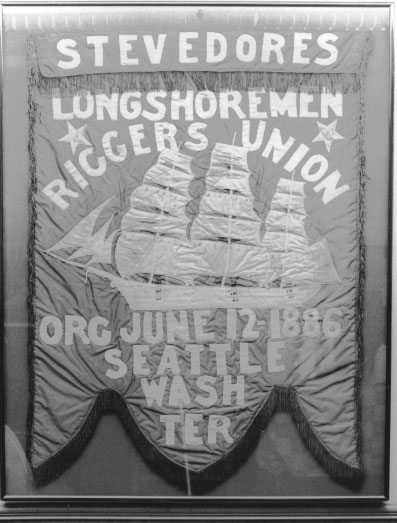

1886 Banner

Unionism began on the Seattle Waterfront in 1886 with the formation of the Stevedores, Longshoremen and Riggers Union. Functioning as part union, part co-operative, the association bid for longshore work contracts. Above are the 1886 Rigger's Union membership card and banner. Used in Labor Day parades and pageants, the original banner still hangs in ILWU Local 19's hiring hall in Seattle. (Photo courtesy Local 23 Collection).

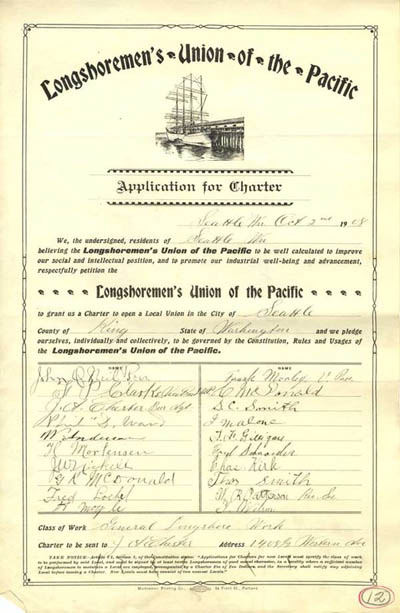

Below is the original charter of the Longshoreman's Union of the Pacific which formed in 1908 and three years later became Local 38-12 of the International Longshoreman's Union. Photo courtesy of the ILWU Archives in San Francisco. Click on the image to see similar charters from other locals up and down the coast.

Longshoreman's Union of the Pacific charter 1908

by Rod Palmquist

Who are longshoremen? The origins of the terms “longshore” and “longshoremen” come from a waterfront manager’s call for casual workers “along the shore” to work on the docks.[1] More specifically, longshoremen are workers whose main job is to load and unload cargo between ships at a dock and the warehouses of a coastal port. In 1934, “longshore work” was broken into many different stages of production, and workers were variously employed as longshoremen, gang bosses, hatchtenders, winch drivers, donkey drivers, boom men, burton men, sack-turners, side runners, front men, and jitney drivers.[2] In the early twentieth century, longshoremen held very strategic jobs for the global economic system, since much more of the world’s commerce used to be transported by ships (as opposed to planes), and because greater labor power was needed to load and unload cargo, compared to the increased use of mechanization in US ports today.

Longshoremen, the Waterfront, and Dynamics between Capital and Labor

In the past, longshoremen were known for their high degree of job mobility. This can be seen, for example, in the ability of Seattle longshoremen to easily move and find work at different ports if they wanted to, especially if working conditions were better elsewhere. [3] Longshoremen’s mobility could sometimes increase their overall bargaining power with waterfront employers, especially in times of labor shortages. When longshoremen began to coordinate their activities more closely with one another during periods of a smaller labor pool, employers were subsequently pressured to coordinate a collective response.[4] A dynamic was then created where both classes had to be strongly united against the other in order to achieve their goals. If one group failed to achieve a high enough level of unity—seen for example, in the San Francisco Riggers and Stevedores Union bargaining with employers on their own, or an Alaskan steamship company breaking ranks with other employers to negotiate with the unions—then the overall bargaining positions of each respective class was weaker.

Geography also influenced the relationship between labor and capital on the Pacific Coast. In the ‘30s, shipping on the West Coast was dominated by the Port of San Francisco, which captured 80% of the Pacific Rim’s maritime commerce alone. Seattle, by contrast, only handled 5% of West Coast shipping (although this was more than Portland and Tacoma’s combined handling totals).[5] Despite San Francisco’s commercial dominance, it was still possible for waterfront employers and steam ship companies to shift their operations between different ports up and down the coast. This meant that if workers decided to shut down one port, employers could isolate local problems by moving shipping elsewhere.

Harry Bridges, the rank-and-file leader of the 1934 Longshore Strike, understood this dynamic well in defining strike strategy: he pointed out that if the longshoremen successfully struck along the entire coast, then “the smallest local [union] in the smallest port could become just as important in the overall strategy for victory, as the many thousands who work…in huge harbors.”[6] Bridges’ observation is a recognition of the waterfront employers’ ability to divert their shipping, but it also is based on an organizing perspective. For example, the Pacific ILA wasn’t completely able to shut down the California Port of San Pedro, but the longshoremen still defeated the employers in the end. Burt Nelson, a rank-and-file leader of Local 38-12 in Seattle, thought that maybe one port could remain open “without impeding a coastwise strike, except for the morale factor.”[7] In some ways then, the battle for control of the waterfront was just as much about perceptions, as hard realities.

Another factor on the waterfront was the conception of union organization, and whether it would be organized along narrow craft lines—such as longshoremen, seamen, or cargo drivers—or whether it would be possible to conceive of a strike on an industry-wide basis, bringing sailors, longshoremen, and Teamster drivers together to close down production in one port. This question would be posed first in the 1916 ILA strike and again in 1934.

Therefore, the hallmarks of the waterfront of the 1930s were the relative labor intensity of longshoring and the function of ports in facilitating economic exchange, dynamics which offered a lot of potential power to the ILA. In theory, if longshoremen could organize themselves in conjunction with other waterfront workers, they had the ability to shut down the entire West Coast shipping industry and hamstring the American economy. This was only true however, if all maritime workers were unified on a coastwise, or coast-wide, basis, as the employers could also organize to pit one port against another. An important test of the ability of the ILA to seize power from their employers came in 1916.

Lessons of the failed 1916 Strike

Employers broke the 1916 strike by employing 400 non-union "independents" who crossed picket lines and worked the ships. This photograph shows "scab herders" organizing strikebreakers on the Seattle waterfront (Local 23 Collection).

In 1915, the International Longshoremen’s Association represented longshoremen in every major West Coast port in the United States.[8] Yet by the end of a 1916 coastwise strike for a closed shop (requiring all workers to join the union), increased wages, standard rules governing longshore work, and other demands, the ILA had been soundly defeated, and union membership dropped substantially as a result, even disappearing in many ports for the next decade. Looking back, the longshoremen union’s International President, T.V. O’Connor, said the main reason why the ILA lost the 1916 strike was because San Francisco broke ranks with the rest of the coast and negotiated a separate contract with the waterfront employers, recognizing the open shop, which allowed individual workers to stay outside of the union, undermining its effectiveness.[9] Given San Francisco’s size and the employers’ ability to divert ships to different ports, this analysis definitely makes sense. In Seattle, there were other factors that contributed to the ILA’s failure in the 1916 strike. Because the history of the Pacific ILA unions is linked together, these local considerations had a big impact on the overall power of the longshoremen in coastwise labor disputes.

In addition to San Francisco’s defection, the members of ILA Local 38-12 were unable to completely close Seattle’s port on their own. This was because the waterfront employers in Seattle managed to successfully recruit scabs, or strikebreakers, to work the ships in port. By June 16, 1916, the Waterfront Employers Union of Seattle (WEU) had “hired 400 ‘Independents’” to work cargo, and by September 21, employers were eliminating their backlog of work through the use of 850 strikebreakers, who successfully loaded ships and allowed them to sail on schedule.[10] Some of these strikebreakers were black workers, who ended up being fired by the employers once the strike was over.[11] It was partly this use of black workers to break the 1916 strike that led Local ILA 38-12 to admit African-Americans—previously barred from membership—into their union, the first Pacific longshore local to do so.[12]

Although the employers’ use of scabs hindered the 1916 strike, the decisions of non-longshore craft unions were very important in keeping Seattle’s port open. For example, even when employers managed to successfully use scabs to work cargo, it would still possible for organized labor to keep a port closed as long as ships don’t enter or leave harbors, and if goods aren’t taken away from, or brought to, docks and warehouses. In Seattle, the Teamsters (who drive transport goods by land) respected the longshoremen’s strike and didn’t deliver cargo to the waterfront. Yet they were only one half of the equation: to keep a port closed also requires the participation of sailors and seamen, the workers who actually operate ships. In 1916, seamen and other marine unions did not strike in sympathy with the longshoremen, which greatly contributed to the strike’s overall failure, according to Ronald Magden.[13]

At the end of 1916, the longshoremen in Seattle and on the Pacific Coast had learned a lot about the precariousness of a craft strike of longshoremen alone, the need to prevent scabs from working cargo and keeping all coastal ports closed, and general lessons on the theory of industrial unionism, the view that different craft workers in a single industry should be organized into one union, combining seamen, longshoremen, and warehousemen on the waterfront. In the future, the seamen and Teamsters would play crucial roles in determining the success of longshoremen in keeping their ports closed.

Establishment of the Fink Hall and Strengthening Employer Control

After defeating the ILA in the 1916 strike, the waterfront employers soon moved to establish open shop conditions where workers were registered and hired through non-union hiring halls, or offered a job informally.[14] A central component of the ILA’s history in the pre-1934 period is waterfront workers’ struggles to control their hiring process. The Waterfront Employers Union of Seattle tried to implement an open shop by creating their own labor bureaus, known to workers as “fink halls,” which would dispatch “casual,” non-union workers to waterfront jobs. The employers’ use of fink halls to hire longshoremen is important because it impacted the degree to which the ILA could effectively organize workers in any given port. The fink halls were hated by the union because it made it possible for employers to blacklist ILA members from regular jobs, hire them only sporadically, and keep union men in the hall until most non-union men were dispatched. In Seattle, the WEU hired Frank Foisie, a labor relations professor from the University of Washington, to run their fink hall. Burt Nelson, a member of Local 38-12 and the Communist Party, was 22 years old when he first started working on Seattle’s waterfront in 1932. Describing how fink halls in Seattle operated under Foisie, Nelson said:

When you came in the hall, you pegged in. There was also a section of organized gangs that didn’t peg in. They got their orders in a different manner… They told you after you got through the evening before to call in at 6:30 a.m. You might get an 8 o’clock start or something else. Or they might tell you to call back at 11 a.m. They could keep you on the tether like that… This is the kind of a setup where men are sitting around waiting to go to work… Wondering whether they were going to be able to earn enough money for rent or groceries for the family.[15]

Some 1916 strike veterans, including William Veaux and Arthur Whitehead, never even got sent out to work from the fink halls.[16] The fink halls were also a major problem for the ILA because they gave longshoremen zero incentive to pay dues to a union, especially when locals couldn’t guarantee that their members would even be given steady work. With a weak union unable to combat a more powerful management, the waterfront employers could work longshoremen to the bone. Lack of union control over working conditions resulted in longshoremen being forced to overload goods in slings, and made them vulnerable to “speed-ups,” which is the name for loading and unloading ships as fast as possible, regardless of safety. Burt Nelson commented graphically on the effects the employers’ control over working conditions had on workers, which deserves to be quoted at length:

I became convinced shortly after working as a longshoreman that five years of this and I would be dead unless something was done. I heard a man who was then the titular head of Pacific Lighterage say, “Give me all you’ve got, averaging 22 years old, weighing 200 pounds, and I’ll wring everything out of them in five years.” We used to carry 120 pound sacks of coffee and lots of raw sugar…I just about fit what that boss wanted. He was a very insulting man. He’d ask you if you could read. It was his tone of voice. Like an old time slave owner who had them standing on a block of wood and looking me over, like a chattel slave...[another boss] used to hang his pot belly over the combing when we were discharging sugar. We would be putting 40 sacks on the load. He would tell us, “Put on 2 more boys” just to show us he could do it. And we had to meet the hook.[17]

Sometimes this “speeding-up” and the employers’ pitting of gangs against each other would result in the loss of lives. Harry Bridges, an Australian immigrant who first started working on the San Francisco waterfront in the 1920s and who would become one of the great leaders of the 1934 Strike, gave the following testimony to the National Longshore Board during the 1934 hearings:

There was one man at least fatally killed and another injured, if not fatally…We were loading copper, and as I say, competing against one another. The gang next to us was in such a hurry to sling the copper that it was slinging over bad loads. Our gang…called their attention to it…My gang boss was there and he cased us back to our own hatch and said, “You mind your own business and get your cargo out ahead of them, that is all you have to do.” About three-quarters of an hour after that, his load went in and fell down into the hold, which is when it killed, as I say definitely, one man and injured another. I think the second man had his leg cut right off. This was absolutely due to the fact that we were competing against each other.”[18]

Faced with all this, it is no wonder that the longshoremen’s main demand in the ’34 Strike was ILA control of all port hiring halls, as the ability to dispatch workers to their jobs was the key to building and maintaining control over working conditions on the waterfront.

The List System

In Seattle, Local 38-12’s attempt to counterbalance the fink hall was the creation of the so-called “list system.” The local found the ability to take on the fink hall when the United States entered World War I in 1917. The war caused shortages in Seattle’s longshore labor supply, and this, along with federal pressure to keep lines of commerce running, greatly strengthened the Local’s bargaining position.[19] The Local soon flexed its newfound muscle by holding two strikes in 1917 and 1919, which forced Seattle employers to hire ILA members through the union hall, rather than the fink hall.[20] The labor shortage and ILA strikes also necessitated an increase in the union’s racial integration: in 1918, over 300 black workers joined Local 38-12.[21] By August 1919, the Local won a wage increase from their employers and a contract guaranteeing that ILA members would be hired according to a union-approved waiting list.[22]

The list was created specifically to protect the ILA’s black members, who faced racism in hiring practices, and to distribute waterfront work more fairly among the workers. Local 38-12’s list system dispatched longshoremen alphabetically by name from the union hall. The Seattle ILA believed that the list system was necessary because union longshoremen faced severe blacklisting, either during shape-ups (the daily selection of workers from the hall) or through the fink halls. During the shape-ups, longshoremen gathered down by the docks early in the morning to wait to be dispatched according to the whims of gang bosses.[23] One former Seattle ILA member named Hulet Wells remembered that during shape-ups “the hiring agent climbed up on a pile of lumber, and pointed his finger here and there at the men he favored.”[24]

Once World War I ended however, a downturn in shipping led to an oversupply of labor. The waterfront employers soon reneged on their previous agreement with Local 38-12, declaring that they would operate Seattle’s docks under open shop conditions and would not abide by the union’s list.[25] The Local struck on May 6, 1920 to retain their dispatching system, but the ILA’s International President, T.V. O’Connor, revoked 38-12’s charter for holding an unsanctioned strike.[26] Having lost the International’s backing and therefore, legitimacy as a bargaining agent, the Seattle Local soon gave up.[27] The Seattle ILA’s strike over the list system would eventually split the union into three, and then later two, separate locals, which created a rift that did not begin to heal until 1925.[28]

The Fink Hall Era and the ILA in the 1920s

With the failure of the 1920 strike, the fink hall gained a much stronger, although not totally secure, foothold in Seattle. The waterfront employers banded together and amalgamated their separate hiring halls into a single employment office, which would register and dispatch all Seattle longshoremen.[29] Following these developments, Frank Foisie created a Joint Organization Committee of employers and longshoremen that functioned as a company-controlled union.[30] Asked whether there was “some semblance of a local” in Seattle during the ‘20s, Burt Nelson said in a 1987 interview with Ronald Magden that every time “working people have tried to get organized…they have been smashed,” and for all intents and purposes Local 38-12 “didn’t reemerge until 1933,” although “there was a small group that were largely employed by the Port of Seattle… [which] had a charter so to speak.”[31] Seattle’s public docks and Port Commission ended up saving the remnants of Local 38-12 from total destruction by Foisie’s fink hall. According to Magden, the Port of Seattle was created in 1911, after ILA Local 38-12 led a campaign to get the city to purchase public docks. The union wanted to wrest control of the Seattle waterfront away from the private employers and transfer ownership to the public, in order to exert more control over working conditions. The employers vigorously opposed this move, but Seattle residents approved a referendum on funding public docks. This opposition on the part of the employers, coupled with the ILA’s initial advocacy for the creation of a public port, led the Port Commissioners to initially become pro-union, and two of the three commissioners in the 1920s were Socialists. As a result of these developments, the Port Commission ended up hiring longshoremen from Local 38-12’s union hall, providing the ILA with some steady work and protecting the remaining union members from the fink hall.[32] Dependence on the Port Commission in Seattle did not bode well for the ILA’s fortunes in the long run, however. Overall, the failed strike of 1920 ushered in an era of fink halls and the hiring of casual and non-union longshoremen, that would last for over a decade until the ILA regained its power in the ’34 Strike.

Next: Part II: The Start of the '34 Strike

[1] National Longshoremen’s Arbitration Board, October 12th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 27, pp.2-3.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Unknown Book, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 2, Folder 44, p.87.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007.

[6] Quoted in Charles Larrowe, “The Great Maritime Strike of ’34: Part I,” Labor History, Vol. XI, No. 4 (1970)..

[7] Interview with Burt Nelson by Ronald Magden, on February 2nd, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 1.

[8] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.75, p.78, & pp.80-1.

[9] Ibid., p.93 & p.97.

[10] Ibid., p.88 & p.95.

[11] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007.

[12] Dana Frank, Purchasing Power (Cambridge 1994), p.27.

[13] Ronald Magden, The 1934 West Coast Longshore Strike, University of Washington Special Collections, Videorecord SPE-251.

[14] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.95 & Ch. 5 generally.

[15] Interview with Burt Nelson by Ronald Magden, February 2nd, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, 5185-1, Box 5, Folder 1.

[16] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.100.

[17] Interview with Burt Nelson by Ronald Magden, on January 13th, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 1.

[18] Testimony by Harry Bridges at National Longshore Board Hearings, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 2, Folder 25, pp.3-4.

[19] Dana Frank, Purchasing Power (Cambridge 1994), p.164.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007; and Dana Frank, Purchasing Power (Cambridge 1994), p.165 Note: Magden claims that 1,000 black longshoremen were hired while Frank says 300 were. There were only 1,200 total longshoremen on the waterfront in 1934, but it is possible that there were much more during a time of war, and when the industry was more labor-intensive in 1918. This author has conservatively hedged his bet at over 300.

[22] Dana Frank, Purchasing Power (Cambridge 1994), p.164.

[23] Thesis, Attitudes Towards Negroes, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 21, p.27.

[24] Hulet Wells’ autobiography, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 2, Folder 42, p.269.

[25] Dana Frank, Purchasing Power (Cambridge 1994), p.165.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.25.

[29] Quoted in Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.155.

[30] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.21.

[31] Interview with Burt Nelson by Ronald Magden, February 2nd, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 1.

[32] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007.