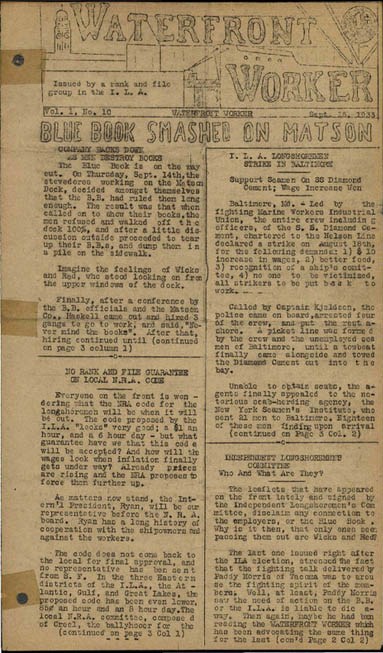

Published by activists associated with the "Albion Hall" group, the Waterfront Worker was a popular and important newspaper that dealt with day-to-day grievances of waterfront workers, promoting rank and file militancy and strong industrial unionism. Click on this image to explore other copies of the publication, provided courtesy of the ILWU Archives. (Copyright (c) reserved)

This essay is presented in three parts.

Click to move to any section:

Part 1: Longshoremen and the Waterfront Before 1934

Part 2: The Start of the Great 1934 Longshore Strike

Part 3: War on the Docks

by Rod Palmquist

Although the ILA was down and out in the 1920s—Local 38-12 only had twenty-four members in 1929—these longshoremen were “true union men” according to Ronald Magden, “who would never give up when the situation looked totally hopeless.”[1] Burt Nelson says the longshoremen knew they “were going to have to fight someday,” and that there were many “rank and file agitators” in the early 1930s talking about the need “for a coastwise organization.”[2] In the midst of the Great Depression, Democratic candidate Franklin Roosevelt won the U.S. presidential election of November 1932, and pushed through reform programs in Congress to save the domestic economy.[3] Included in his New Deal legislation was the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). Labor found hope in Section 7a of the NIRA, which “required that every National Recovery Administration code, guaranteed to employees the right to organize and bargain collectively without interference from their employers.”[4] The passage of the Act, in conjunction with an increase in Northwest shipping activities in 1933, led the ILA in Washington and Oregon began to look toward resurgence.[5] According to the minutes of the company union in Seattle, “as a result of the N.I.R.A. together with organizing solidly in the I.L.A.,” the longshoremen “were feeling their power” and began to take “disciplinary action in their own hands against offending employers.”[6] One employer, W.D. Vanderbilt, said that the longshoremen aimed “to clean our house for us,” since workers did not like, among other things, the “hiring of unregistered men…independent of the central registration system,” or the “speeding up of work beyond all reason.”[7] Although the seeds of the ILA’s revival were sown before these political developments, they should not be underestimated. Burt Nelson sums it up best, observing that:

The shipowners were making money hand over fist [in the 1920s]. It was the golden age of capitalism...It was in this kind of setting that the move to once again organize a longshore union started. It began before the enactment of the National Recovery Act. That gave it tremendous impetus. I recall John L. Lewis hung the rigging on Franklin Roosevelt when Lewis in a big speech said, ‘Brothers! The President wants you to join the union.’ Well, Roosevelt had not said that but he didn’t dare deny it…That gave another big lift to it.

With the political winds changing in their favor, a showdown was at hand.

Prelude to the Strike

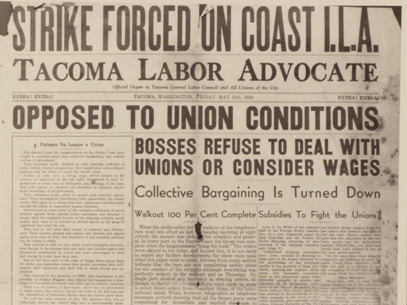

The start of the 1934 strike is announced by the Tacoma Labor Advocate

(Local 23 collection)

Employers had good reason to be afraid. Arguably ineffective for years, in 1933 the ILA began to fight back by asking the waterfront employers to adopt shipping codes. The demand to create a shipping code was based on section 7b of the NIRA, which “authorized industries to voluntarily prepare operational codes that would stimulate economic recovery and…recognize the needs of working people.”[8] On September 13, 1933, ILA representatives in Frank Foisie’s company union (longshoremen who held seats on the Joint Organization Committee), requested control over the dispatching of men to jobs, asked to negotiate a new collective bargaining agreement through the ILA, and for wage increases.[9] The employers refused to comply with these demands, saying that wage increases would have to wait until after negotiations in East Coast ports were concluded.[10] When these negotiations were finalized, the employers offered the Seattle longshoremen the same concessions given to New York longshoremen.[11] Local 38-12’s representatives on the Joint Organization Committee rejected the offer on November 15, and stood firm on a request for higher wages along with ILA recognition.[12]

While the Seattle Local was negotiating with employers, the ILA Pacific District had sent a negotiating team to the federal shipping code hearings that were being held in Washington, D.C.[13] The NIRA board received proposals from both the waterfront employers and the ILA until February 3, 1934, when the seventh draft of the shipping code was rejected by employers.[14] Instead the employers—who didn’t want the ILA recognized as the bargaining representative of longshoremen—tried to discredit the union. Burt Nelson and Wayne Moisio, a rank-and-file Seattle ILA member, were talking about the employers’ political maneuvering in a cab:

I was working at West Waterway Dock on the Jefferson discharging sugar. At one o’clock we were going back to work and the superintendent came up and said, “We’re all going over to the Massachusetts fire station and vote.” I don’t know how many people knew we were going to vote. I knew it. It was whether we wanted the employer-employee representation plan or the union to represent us. It was the 3rd of March…Wayne Moisio and I rode in the same cab. He said, “What kind of fools do they think we are? Don’t we know why they are giving us this taxi ride.”[15]

The employers were disappointed by the response of the longshoremen, as Nelson, Moisio, and a majority of workers like them voted resoundingly against accepting the representation of a “yellow” company-run union.[16]

At the ILA District Convention in San Francisco on February 25, 1934, the longshoremen demanded that the Waterfront Employer Associations in each port bargain with them on a coast-wide basis.[17] West Coast trade tonnage had increased again in 1934 for the second year in a row since the start of the Great Depression, and the waterfront employers raised their rates (leading to higher profits), but refused to pass on wage increases to their employees. “This is where the rub came in” for the longshoremen, Magden recalled, and while “they took it in ’33, they refused to take it in ’34.”[18] The snub by the employers in not giving the West Coast longshoremen a raise, coupled with the prospects for organizing offered by the NIRA under a labor-friendly governmental administration, were the main immediate causes of the ’34 Strike.

The ’Frisco District Convention Another factor that led to the start of the strike was the 1934 ILA District Convention in San Francisco. During this conference, the longshore locals of the West Coast agreed that employers should give them control over hiring halls, only negotiate contracts on a coastwise basis, provide for a thirty-hour work week, increase wages, change policies such as the “speed-up,” and officially recognize the union.[19] Moreover, the Convention also agreed to not arbitrate these demands, and to halt negotiations and conduct a strike vote among the rank and file if employers didn’t respond by March 7 of the same year.[20] When longshoremen met with the San Francisco Waterfront Employers Association, they were told by Thomas G. “Tear Gas” Plant—a Vice-President of the powerful American-Hawaiian shipping line—that the shipowners “could not form a coastwide bargaining organization,” and that ILA recognition “was absolutely out of the question.”[21] Although the waterfront employers balked at the workers’ demands, especially those for union control of the hiring halls and coastwise recognition, the longshoremen didn’t compromise their main positions for the duration of the strike. This made the initial formation of the ILA’s goals at the District Convention very important; yet the longshoremen might never have had the chance to formulate them, had it not been for a revival of longshore unionism in San Francisco.

San Francisco’s Blue Book company union

After the Riggers and Stevedores Union, the ILA affiliate in San Francisco, cut a deal with the waterfront employers that effectively ended the failed 1916 strike, the ’Frisco longshoremen’s position weakened until the union was destroyed by the employers’ fink hall. In place of the independent ILA affiliate, waterfront employers forced San Francisco longshoremen to join their new company-run “Blue Book” union, which was named after a pale blue membership book (probably to distinguish it from the Riggers and Stevedores’ red-hued member roster).[22] According to employer correspondence, the purpose of the Blue Book union was “to keep out all the reds that were in the old Riggers and Stevedores,” as Communists were often seen as labor agitators .[23] More generally, the company union served to investigate whether San Francisco longshoremen had any past affiliation with the Riggers and Stevedores Union, rewarding workers who passed this screening process with preferential employment.[24]

The Blue Book union is essential to the general history of the ’34 Strike because of the strategic importance of the Port of San Francisco on the West Coast. With a strong company union in place at San Francisco, there was no hope for the longshoremen up and down the West Coast to win coastwise recognition or ILA-controlled hiring halls. In short, the Blue Book union had to be destroyed, and it was partly through the efforts of organizers in a Communist “dual union,” the Marine Workers Industrial Union (MWIU), that brought about the demise of the fink hall in San Francisco.

After ILA loyalists and former Wobblies (the nickname of the Industrial Workers of the World, an industrial syndicalist union that was most active in the U.S. around the First World War) began a reorganizing drive in 1933, Sam Darcy, the Communist Party leader of the Party’s Southwestern district, decided to make a break with the dogmatic “dualist-union” ideology then in vogue, which aimed to form a left wing within the labor movement by creating radical unions in opposition to existing union formations. Instead, Darcy created a radicalized left-wing of rank-and-file longshoremen within the new San Francisco ILA Local.[25] Darcy thought that engaging in “competitive MWIU recruiting at that point would have been suicide,”[26] since it was impossible to “break down the agitation against our union and against our Party on the waterfront.”[27] Darcy started out by getting MWIU activists to join with radical rank-and-file longshoremen in the ILA, such as Harry Bridges, to create an informal organizing contingent known as the Albion Hall group (named after a building where they met).[28]

According to historian Howard Kimeldorf, the Albion Hall group “was just the vehicle the party needed to make contact with the rank and file.”[29] Albion Hall soon gained more influence among San Francisco longshoremen by recruiting rank-and-file leaders like Bridges, and utilizing these members’ knowledge of organizing such effective projects as the Waterfront Worker newspaper, which was a periodical that covered “pork-chop” day-to-day issues in a very accessible way for its waterfront audience.[30] Looking back in 1939, Harry Bridges commented that members of the Albion Hall group were “the ones who received complaints from the men and relayed them to the foremen.”[31] Bridges went on to say that Albion Hall longshoremen would also take “specific action against the speed-up by slowing up at the winches and in the hold…Other men on the docks watched...saw that we were getting away with it, and began to imitate us.”[32]

The Matson Uprising in San Francisco

Although old loyalists and IWW members started the reorganization of the ILA in San Francisco, the Albion Hall group and other non-Communist rank-and-file longshoremen made a huge contribution to these efforts by winning an important victory against the port’s largest employer, the Matson Navigation Company. In September 1933, after workers on Matson’s docks were fired for refusing to show their union books to a Blue Book official, a mass of longshoremen walked off the job and burned their “fink books” in an empty lot along the waterfront.[33] This incident worried Matson, who quickly gave into the men, asking them to work on their ships whether or not they had a fink book.[34] The newly conciliatory attitude from one of the West Coast’s most powerful employers didn’t last long however, and within a matter of weeks, four ILA longshoremen were fired by Matson for wearing union buttons. When local ILA leadership failed to take action in response to the injustice, a unilateral strike against Matson was called via the Waterfront Worker, and all of the longshoremen working on Matson’s docks “hit the bricks.”[35] Matson gave into the strikers’ demands within a week, and re-hired the four fired longshoremen. According to Bridges, “from that time on, the union was established, it was recognized, and it was in business.”[36] Another famous San Francisco longshore leader, Henry Schmidt, supported Bridges’ views and agreed that the Matson strike “was a big victory...all of a sudden the fellows realized that they had some power.”[37] According to Magden, the Matson Strike was important, but the pivotal moment for the union occurred when longshoremen burned their Blue Books and saw the company union and hiring practices as their target.[38] Magden argues that the men “were fed up and willing to do something about it,”[39] and although the strike was indeed a successful act of defiance, the Blue Book was the main tool that employers used to discriminate among different San Francisco longshoremen. Without identification and previous information on employment records, it was much harder to blacklist rank-and-file longshoremen. In any case, Henry Schmidt says that after these two events, “more men [were] coming into the union.”[40]

Although the extent to which the Albion Hall group was responsible for saving the ILA in San Francisco is debatable, the group used their newly gained political capital wisely. At the ILA District Convention, which was held in San Francisco in 1934, it was the pressure of Albion Hall members that forced delegates from other ports to include union control of hiring halls and coastwise recognition in the ILA’s new requests to the waterfront employers. When the employers balked at these demands, and with the ILA up and running again in San Francisco, the stage was set for a major test of will between labor and capital on the West Coast.

Roosevelt Tries to Intervene

After its demands were rejected by the employers, the ILA Pacific District issued a strike ballot to its membership. The results of the vote came in with 6,616 ILA members in favor of striking and 590 opposed.[41] On the day before the longshoremen were scheduled to stop working, President Roosevelt asked the ILA to call off the strike until a board could investigate the issue and mediate between the union and employers. One explanation for Roosevelt’s attempt to avert the coastwise strike is that longshore stoppages threatened the U.S. economy’s recovery from the Depression, which Roosevelt’s Administration had been elected to implement.[42] Bill Lewis, the ILA’s Pacific District President, wired Roosevelt back saying that the longshoremen were “postponing strike action at this time…believing that evidence of the justice of our cause is bound to change present unbearable conditions.”[43]

Roosevelt’s board started hearings on March 27, 1934th. In a letter to the president on April 24th, the board reported that they had proposed an agreement between the longshoremen and employers on April 3rd. In this agreement, which was confined to San Francisco, the board proposed that elections be held among longshoremen to determine a representative leadership, collective bargaining should be limited to longshoremen employed within the port’s jurisdiction, and management of the hiring halls should be jointly shared between the union and employers. The reason why the board’s April 3rd agreement was not coastwise in scope was because the board argued that the “local differences” in each port made it necessary for each city to be “handled separately.”[44] Not yet spurred by a radicalized rank and file, the District Officers of the ILA accepted the April 3rd agreement with reluctance, and the Regional Labor Boards began holding representational elections.[45]

In the meantime, ILA negotiators still tried to get the employers to agree to a coastwise settlement, but they held out against the union. On April 7th, the president’s board ruled that the coastal bargaining request of the longshoremen violated the April 3rd agreement.[46] When it looked like the longshoremen would settle, San Francisco Local 38-79 suddenly voted to break off all negotiations with the waterfront employers if no progress was made in mediation sessions by May 7th.[47] Nothing was accomplished before this new deadline, and the ILA’s Pacific District President Bill Lewis told the District Secretary, Jack Bjorklund, to contact the locals and ask them to vote immediately on whether to strike on May 9th.[48] By May 8th, all major West Coast ports had voted in favor of striking, except for Seattle and San Pedro, who hadn’t held their votes yet. Apparently, many Tacoma longshoremen thought that the Seattle Local was a weaker link in the longshoremen’s coastal chain, and ILA delegates from Tacoma and Everett went to Local 38-12’s meeting later that night to argue in favor of a strike.[49]

When Seattle members were discussing whether or not to strike, at first over half of Local 38-12 was against quitting work. After ILA members, including Dewey Bennett, William Craft, Ed Harris, T.A. Thronson, William Veaux, and Paddy Morris spoke in favor of the strike, and when it was announced later that night that San Pedro had recently voted in favor of “hitting the bricks,” a majority of Seattle longshoremen agreed to strike the next day.[50] When asked about the start of the 1934 strike, T.A. Thronson of Tacoma recalled:

The actual strike was called for the 9th of May, 1934, and at that time all the seafaring groups and ourselves had agreed on the date and time…the coast was in a very quandary in regard to the strike. San Pedro… [and] Seattle hadn’t voted to go on strike by the 8th of May, and then they made up their mind on midnight, but we were unified for the morning of the strike.[51]

A new dawn: the ’34 Strike begins

Activists waiting strike deadline, 1934

The Pacific District ILA’s Strike of 1934 began on the morning of May 9th when over 12,000 longshoremen struck from Bellingham, Washington in the north, to the port of San Diego, California in the south. According to Jonathan Dembo, only 75 longshoremen along the entire Pacific Coast crossed strike picket lines.[52] With such unity among the longshoremen, the employers mainly concentrated their tactics on keeping the larger ports of San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Portland open through the use of scab labor or by force. Striking longshoremen in sixteen smaller ports, by contrast, succeeded in keeping their waterfronts closed down for the duration of the strike.[53]

In Seattle, out of a workforce of 2,000 longshoremen, three scabbed and the rest struck,[54] but there were 200–300 members of the union who failed to show up for picket duty on the first day of the strike.[55] One explanation for this initial show of uneven solidarity on the part of Local 38-12 was offered by Dewey Duggan, a member of the Seattle Local’s twenty-five member strike committee, who said: “We didn’t know each other when the strike started because each gang worked at only certain docks… [and] the bosses kept us from meeting each other.”[56] Solidarity and trust can not be built overnight, but despite this initial obstacle, 38-12 quickly organized a press committee, a flying squad of strikers “to handle emergency situations,” a relief committee to extend credit to strikers’ families, and a soup kitchen to provide members with meals in the union hall.[57]

Securing Teamster support and the final preparations

Local 38-12 also made sure to ask for support from the wider Seattle labor movement. At a Seattle Central Labor Council meeting on May 9th, Local 38-12 secured financial support from the Teamsters and the Masters, Mates, and Pilots. Although Dave Beck, the conservative leader of the Teamsters in Washington and Oregon (who went on to become the Teamsters’ International President in the 1950s), was consistently opposed to striking in sympathy with the longshoremen, the same was not true for his rank and file. Despite Dave Beck’s adamant view that the Teamsters wouldn’t strike, the Seattle ILA pleaded with the Teamster rank and file before May 9th not to work any waterfront freight in sympathy with the longshoremen.[58] By the end of the day on May 9th, Frank Brewster, a Teamster delegate, contradicted Beck’s promises by announcing that the Teamsters’ membership would not handle any cargo on Seattle docks.[59] The Teamsters honored this promise in Seattle during the entire length of the strike, in spite of Beck’s opposition.[60] According to Ronald Magden, who conducted extensive interviews with Dave Beck and wrote an unpublished history of the Teamsters in Washington State, “the men didn’t follow Beck.”[61] According to Magden, Beck said he tried to “never take votes in meetings” of the Teamsters, but he also admitted that he “never challenged the rank-and-file once they got their mind made up.”[62] Beck would attempt to individually thwart the longshoremen’s strike, but the rank and file of Teamsters Local 174 in Seattle “held a wildcat” sympathy strike, “spontaneously deciding to side with the longshoremen,” according to Magden.[63]

Meanwhile, members of the Waterfront Employers Association of Seattle were busy making their own preparations. The Seattle employers organized themselves into counter-strike committees in charge of policy, publicity, the recruitment and housing of scabs, transportation, and finances.[64] All of the WEA members agreed that no one employer should take any action without the approval of the others, and they began looking for ships to serve as floating hotels for scabs, as well as trying to secure promises from the City’s Police Chief to protect strikebreakers—though this last attempt would prove futile, for reasons to be explained later.[65]

On May 10th, the counter-organizing of the employers paid off. There were reports of 150 scabs working on three piers, while the Alaska Steamship, Pacific Steamship, and Pacific Lighterage companies claimed to have 250 men working on the docks.[66] The next day, 200 scabs were said to be working six ships, and in response to a public request by U.S. Senator Robert Wagner for the strike’s arbitration, Dave Beck told Teamsters Local 174 to start bringing cargo to the waterfront again, although the Teamster rank and file ignored this order.[67] By May 11th, there were conflicting accounts of how many strikebreakers were on the waterfront, with one source estimating that as many as 650 scabs were unloading cargo.[68]

Taking back the initiative: Gauntlet Day

ILA member Phil Green escorts the last scab off

the Seattle waterfront during "gauntlet day" (Local 23 collection).

Hearing reports that scabs were working cargo in Seattle, ILA Locals in Tacoma and Everett realized that Seattle Local 38-12’s pickets needed to be strengthened. In the early morning of May 12th, 850 longshoremen from Tacoma and Everett went to Seattle to close the port, in an event that came to be known as “Gauntlet Day.” This operation was timed in the middle of the night for an important reason. According to Magden, one highly notable aspect of the 1934 Longshore Strike in the Northwest was the degree of strategic intelligence that the ILA had in advance about their employer’s plans. Unknown at the time was the fact that George Soule, a leader of the ILA’s Tacoma Local, was in a personal relationship with Elsie Doe[69] who worked as a secretary to the Waterfront Employers Association. Magden found this in an interview with Elsie, who didn’t want her role in the strike to be revealed until after she died. As the employers’ secretary, Doe recorded the minutes of all the WEA’s meetings and heard everything that the shipowners planned vis-à-vis the strike. All the proceedings of the employer’s meetings were relayed by Doe to George Soule and the ILA, with the result that the union knew every move the employers were planning to make during the strike.[70] One significant piece of information given to the union before Gauntlet Day was that the employers had two spies on both the Tacoma and Seattle union executive committees. In order not to tip off their bosses, the Tacoma Local met without the labor spies’ knowledge, at five in the morning, to prepare to go to Seattle and open the port.[71]

Later on the morning of May 12th, 2,000 ILA longshoremen from Local 38-12, along with members of the Tacoma, Everett, and Aberdeen Locals, drove strikebreakers away from the Seattle waterfront, in an event known as “Gauntlet Day” because of the way longshoremen forcibly removed almost every scab from Seattle’s docks. Gordon “Buck” Wiley, a Seattle longshoreman who was a professional boxer in the 1920s and a member of 38-12 in 1934, recalled the events:

Tiny Thronson…came down with a gang from Tacoma…He said “I work in the basement same as you guys.” …When we got organized that day we went all around the waterfront. The whole bunch of us, a big gang. Went to Alaska Steam, Piers 1 and 2, then at the foot of Yesler [Way]. We got a bunch of them out there, lined up, and they all came out of there. Then we went down to the old Nelson Dock where a group of young University of Washington boys working there. They were discharging oranges. We got them out. From there we went down to American-Hawaii, at Stacy and Landis, from there we went to East Waterway. The Seattle bunch had not done that until the Tacoma bunch had come over and got us going.[72]

Burt Nelson, was also present at these events, offered a different analysis on the importance of the Tacoma longshoremen in shoring up the Seattle Local’s efforts. Burt says Tacoma’s “big speech on the platform…is how they came over and saved Seattle. Well, they came here but it isn’t true that they saved Seattle. All of the rest of the strike they were trying to keep 38-12 from running the finks off the front.”[73] Although Nelson’s views are supported by later events, it is important to keep in mind that a big rivalry existed between the Tacoma and Seattle longshore locals, and that both interpretations contain partial truths.

In any case, the presence of Tacoma longshoremen clearing out scabs side-by-side with the members of Seattle’s local—in spite of the rivalry that existed between the two groups—was a strong show of solidarity, and their combined forces quickly shut down the port. Andy Jenkins, a black longshoreman who was the son of one of 38-12’s first black members, Frank Jenkins Sr., and the younger brother of Frank Jenkins Jr., another Seattle leader, started working on the waterfront in 1928. Andy Jenkins worked for the American Mail Line at Pier 41 (now 91), participated in the events of Gauntlet Day, and remembers the height of the drama:

They had a gauntlet at Pier 2 Alaska Steam. Some of the scabs jumped overboard, but the rest of the scabs had to walk through a longshoremen’s gauntlet up to Western Avenue. I was standing there. I was just a kid. A nobody. This guy that I was standing behind was Percy Green, a longshoreman. All of a sudden he jumped up and ran among the scabs, grabbed one guy and started beating the hell of him. He grabbed these knucks from the hand of the scab and turned to me. “You’re Frank’s brother aren’t you? Beat it!” And he gave me these knucks. We became friends after that and one time I told him I still had the brass knucks and would he like them. He told me, “You know if they would have caught me, I’d have got 5 years.”[74]

Perhaps one reason why Percy Green was also able to get off the hook was because the police held back from trying to impede the longshoremen on Gauntlet Day. In fact, there were fifty Seattle Police Department officers on the waterfront who simply stood by and watched the longshoremen clear out the strikebreakers. One reason for the policemen’s uncharacteristic complacence was due to the fact that the soon to-be-replaced Chief of Police, L.L. Norton, was a former longshoreman, and ordered his men to not interfere with the union’s activities.[75]

The ILA’s clearing of strikebreakers from the Seattle waterfront was important for two main reasons. First, the scab clearings gave the ILA greater self-confidence, as it was in many ways the biggest victory for the Local since the founding of the first longshore union in 1886.[76] Second, Gauntlet Day was unique within the wider history of the 1934 Longshore Strike because it involved four separate ILA locals cooperating to close a single strategic port. While Tacoma ILA members might not have thought highly of the longshoremen in Seattle, they also recognized the city’s importance for the strike as the biggest port in the Northwest, and their acts of solidarity, alongside men from Everett and Aberdeen, lent strength to the ethos of coastwise unity.

Scabbing and solidarity organizing at the University of Washington

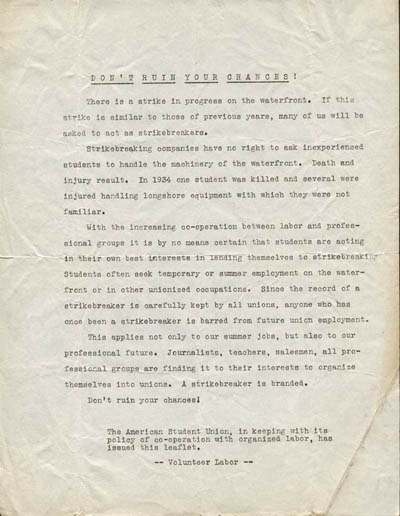

Student Leaflet. Presumably circulated during the 1936/1937 strike,

this leaflet issued by the American Student Union describes the

perils faced by student strikebreakers during the 1934 strike

and urges current students not to scab. (Magden collection).

At this point it is appropriate to show how much the ’34 Strike affected the greater city of Seattle, by briefly looking at the effect of the strike on the University of Washington. According to a University of Washington (UW) anniversary project on the 1934 Longshore Strike, the “employers canvassed the fraternities, signing up over 100 students” to scab on the waterfront.[77] According to this source, Hugo Winkenwerder, then President of the University, and Herbert Condon, the Dean of Men, “objected vehemently to student strikebreaking and denied the companies docking privileges at the Oceanography wharf, when they tried to pick up the students” on campus.[78]

The problem with this version of events however, is that it is contradicted by the oral histories of the longshoremen. Burt Nelson for example, says that the UW President only objected to the employer’s use of students as strikebreakers “following the 1934 strike.”[79] In fact, the head UW football coach “was largely responsible for” allowing shipping companies to “hustl[e]…strike breakers wherever they could get hands” on them, including “a big part of the…football team.” Del Castle, then a UW student and later a longshoreman and member of 38-12, reveals even more of the story. Castle was a member of what was probably the UW’s first student-labor solidarity organization, and remembered:

There was a group of young radicals who wanted to support the strike…We got together and distributed leaflets on campus…At around 7 am we’d put them on the desks in each of the buildings. We couldn’t cover the whole campus, but each one of us would take a building…a campus cop showed up and told me to come with him. He took me to his office to give me a lecture about how dangerous this might be. He was patting his sidearm as he was talking to me. Then he dismissed me. I went back to where my fellow students were and reported what happened. We agreed that it wasn’t going to stop us. There were about 20 of us. We even discussed the longshore strike with merchants on University Way. We didn’t have much effect, because the University Administration, the newspapers…and everybody else was against the longshore strike, [but] we circulated the rumor that anybody who went down to the waterfront would get hit over the head with a 2 x 4. That word went around the campus quite a bit.[80]

What Castle and Nelson’s testimony show is that support for the strike in the ivory tower was divided. This is supported by evidence from the University of Washington Daily, the student-run newspaper. According to an article titled “Strikers Appeal To Students On Fraternity Row,” “30 members of the International Longshoremen’s union…visited fraternity row yesterday to stage a peaceful ‘corner rally’ before 50 students.”[81] This outreach was undoubtedly carried out by the union to protest the scabbing of fraternity students reported by Burt Nelson. On the other hand, there were also UW students who supported the ILA: the Daily also reported on “Liberal-minded students crowd[ing]…the meeting of the University Luncheon club” to hear a debater “explain the real importance and meaning of the longshoremen’s strike.” Afterwards, the same article wrote that “a collection of over four dollars was taken up from the students present at the meeting to be used to supply hot coffee to striking longshoremen and others working on the picket line.”[82]

This vignette from the University of Washington shows how the ’34 strike reached into even the most privileged corners of Seattle’s society, as the strike escalated during the summer of 1934.

Next: Part III: The War on the Docks

[1] Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, February 7th, 2008.

[2] Interview with Burt Nelson by Ronald Magden, on January 13th, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 1.

[3] Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (HarperPerennial, 1990), p.382.

[4] Ibid., p.54.

[5] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.56.

[6] Ibid., p.57.

[7] Ibid., p.57.

[8] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.194.

[9] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.61.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid., pp.61-2.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., p.63.

[14] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), pp.195-7.

[15] Interview with Burt Nelson by Ronald Magden, on January 22nd, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 1.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.67.

[18] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007.

[19] See Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.69; and Howard Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets? (Berkeley 1988), p.89.

[20] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.69.

[21] Ibid., p.69.

[22] See Howard Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets? (Berkeley 1988), pp.35-6.

[23] Ibid., p.36.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid., pp.82-87..

[26] Ibid., p.87.

[27] Ibid., p.84.

[28] Ibid., p.87.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid., p.88.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid., p.89.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Henry Schmidt, Secondary Leadership in the ILWU 1933-1966, University of California (1983), p.68.

[38] Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, February 7th, 2008.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Henry Schmidt, Secondary Leadership in the ILWU 1933-1966, University of California (1983), p.68.

[41] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.198.

[42] Paraphrased from Jonathon Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State (Garland, 1983), p.573.

[43] Telegram, Lewis to Roosevelt, March 22nd 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 4.

[44] National Longshoremen’s Board Letter to Roosevelt, April 24th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 4, Exhibit A, pp.1-2.

[45] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.75.

[46] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.198.

[47] Ibid., p.199.

[48] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.75.

[49] Ibid., p.76.

[50] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.199.

[51] Ronald Magden, The 1934 West Coast Longshore Strike, University of Washington Special Collections, Videorecord SPE-251.

[52] Jonathon Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State (Garland, 1983), p.574.

[53] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.201.

[54] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.77, see also Jonathon Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State (Garland, 1983), p.574.

[55] Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, February 7th, 2008.

[56] Quoted in Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.202.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007.

[59] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.203.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, February 7th, 2008.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), pp.203-4

[65] Ibid., p.203.

[66] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.80.

[67] Ibid., p.81.

[68] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.206, this contradicts Markholt.

[69] Elsie’s real surname is not used in accordance with Ronald Magden’s wishes.

[70] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007. To my knowledge this information has not been made public.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Interview with Gordon Wiley by Ronald Magden, on May 6th, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 13.

[73] Interview with Burt Nelson by Ronald Magden, April 28th, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 3.

[74] Interview with Andy and Renee Jenkins by Ronald Magden, July 7th, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 8.

[75] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007.

[76] Ronald Magden, The 1934 West Coast Longshore Strike, University of Washington Special Collections, Videorecord SPE-251.

[77] University of Washington Libraries, Strikes! Labor and Labor History in the Puget Sound, online exhibit (1999).

[78] Ibid.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Interview with Del Castle by Ronald Magden, November 24th, 1986, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 14.

[81] Undated UW Daily Article #1 in author’s collection. The author is trying to find the exact date in 1934.

[82] Undated UW Daily Article #2 in author’s collection. The author is trying to find the exact date in 1934.