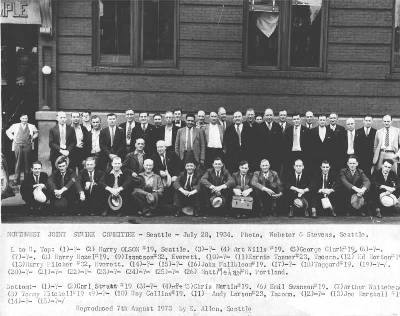

The Northwest Joint Strike Committee, pictured outside the Seattle Labor Temple in 1934 (Ronald Magden Collection).

This essay is presented in three parts. Click to move to any section:

Part 1: Longshoremen and the Waterfront Before 1934Part 2: The Start of the Great 1934 Longshore Strike

Part 3: War on the Docks

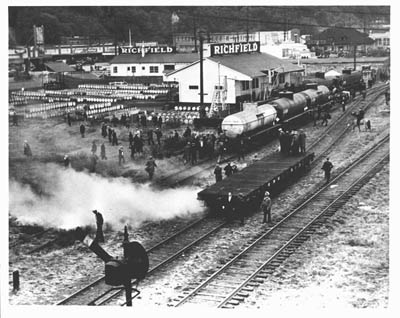

Alaska Steamship Dock

The Port of Seattle was the lifeline to Alaska, a fact that proved critical in the 1934 strike. This photo shows the Alaska Steamship Co. dock earlier in the century (Ronald Magden Collection)

by Rod Palmquist

The longshoremen’s massive show of solidarity on Gauntlet Day shocked waterfront employers. One Seattle representative of the shipowners commented that “within a few days all work at Pacific Northwest ports had to cease, owing to the violence by strikers and lack of police protection…the strikers took over entire control of the waterfront.”[1] Later on the evening of Gauntlet Day, members of the Waterfront Employers of Seattle asked the mayor and police for “assurances of future protection from the…longshore ‘mob.’” [2] Seattle’s mayor, John Dore, went back and forth on whether or not to use the city’s police to intervene in the strike, and he eventually decided to pass the decision on to Washington’s Governor, Clarence Martin. Dore asked Martin to send the National Guard to Seattle in order “to avoid bloodshed and the tying up” of the port. After meeting with the employers and then the longshoremen, Governor Martin, who had previously endorsed the ILA’s strike,[3] refused to call out the National Guard and decided to wait for assistance from President Roosevelt.[4]

Rioting erupts downtown

The Alaska Building riots were the “worst of the strike in Seattle” according to Magden, but a full evaluation of these events requires more information than was available to this author. Even if Magden’s assessment is accurate (which is likely), it doesn’t seem as if the police were involved in these riots to the extent they were in later confrontations during the strike. The Alaska Building Riots in the early days of the strike mark the start of real street conflict in Seattle, which reached a climax in a battle with police at Smith Cove in June.

The need for greater coordination

Before looking at these later confrontations with the police and state institutions, it is necessary to consider other aspects of the strike—such as the issue of allowing Alaskan-bound ships to proceed, and failed attempts at negotiating a compromise—that happened before the state officially declared war on the ILA. When the longshoremen were meeting with Governor Martin, Thomas Wilson, a manager of the Alaska Steamship Company, brought up the issue of how the longshoremen’s strike was affecting the United States’ most remote territory. Because Alaska depended so heavily on maritime transport for vital supplies, Wilson argued that an exception to the strike should be made by the longshoremen for necessary goods bound to the region. The ILA voted to work one ship for Alaska, but only “after the owners agreed to union recognition, wages and working conditions.”[7] One ship didn’t prove to be enough to feed all of the territory, however, and soon the ILA began to feel the weight of public opinion, especially after May 22nd articles reported that Anchorage’s supply of butter and eggs would be gone in a little over a week.[8] In spite of these dire forecasts, it is interesting to note that when the Alaskan-bound ship left Seattle, much of its first cargo was beer.[9]

At the same time that the ILA was faced with the problem of the Alaskan shipments, the longshoremen were joined in their struggle by a sympathy strike of seamen, which eventually included the Sailors, Marine Engineers, Firemen, Cooks and Stewards, and the Masters, Mates, and Pilots unions. The ILA was learning from its mistakes in 1916 by collaborating with the seamen and also reaching out to the Teamsters. Although there was fear of the Seattle and San Pedro ports opening up, all of the ILA unions on the West Coast were cooperating together, and no one local negotiated a settlement on their own. Faced with the huge task of keeping important ports like Seattle closed, and with the problem of Alaska looming on the horizon for the ILA, the Puget Sound longshoremen soon realized that they needed to achieve even greater coordination.

Formation of the Northwest Strike Committee

The Joint Northwest Strike Committee was created after Tacoma asked all ILA locals in the Pacific Northwest to meet to discuss releasing the Pacific Alaska Fisheries Company’s cannery ships, which the Seattle Local had refused to work.[10] The committee was formed on May 24, 1934, and was comprised of sixty-six delegates representing twelve ILA Locals in Washington State and the Columbia River basin. Although the initial purpose of the Northwest Strike Committee was to figure out what to do with Alaska cargo, it came to serve “as a general strategy board” for the Northern ILA Locals.[11] The formation of the Northwest Strike Committee is very important in reviewing the specific history of Local 38-12; as Burt Nelson said, “for the time [the committee]…was in existence,” Seattle’s own respective “strike committee didn’t function much,” becoming more of “a housekeeping committee.”[12] What seems to have happened, then, was that either the Northwest Committee became the highest limited decision-making group—other than the rank-and-file—during the strike, or that because the Committee was based in Seattle, Local 38-12 invested more of its energy in this wider body rather than their own strike committee.

In any case, the Northwest Strike Committee represented a greater sophistication of governance within the ILA Pacific District. Before the Committee’s initial meeting, the organization of the strike was administered primarily by District Officers and a negotiating team that was sent to San Francisco. But the Northwest Strike Committee and its counter-part in the south, the Joint Marine Strike Committee in San Francisco, soon offered rank-and-file union members a new way to keep their leaders accountable and more effectively formulate coastwise demands and policies.

There are many examples in the Strike Committee’s minutes that show a high level of rank-and-file involvement in decision-making processes. When Paddy Morris, a leader of the 1934 strike and a longshoreman from Tacoma, was acting as the spokesperson for a sub-committee empowered to negotiate terms with Alaskan shippers, he presented a report recommending that the Strike Committee accept the so-called “Alaska Agreement.” Committee delegates from Seattle and Everett immediately objected to this motion, arguing “that all questions before them must go back to the Rank and File before any definite action can be taken.”[13] When Morris’ sub-committee recommended that the Everett and Seattle delegates assume full power to act on behalf of their locals, “as it would be useless to continue further negotiations without such power,” the delegates responded by saying “it would take a Philadelphia lawyer to make their Rank and File see along such lines.”[14] Greater rank-and-file control over the Strike Committee is also illustrated by how any proposals to take major actions, such as settling the strike, were required to be sent back to all Northwest Locals for consideration.[15]

The highly democratic and participatory characteristics of the Northwest Strike Committee also merit historical attention. Besides the Strike Committee’s use of parliamentary procedure, roll call votes, and quorum calls, each Northwest Local was represented by delegates and allotted votes in relative proportion to how big a port was, or according to the size of their membership.[16] If a certain local couldn’t often send delegates—the position of the Oregon ports, given that meetings were held in Washington State—the Committee would almost always make sure to transfer proxy votes to a different port.[17] In addition to being conscious about whether the Committee’s sixty-six delegates had full power to represent their locals and in giving voice to all of the Northwest ports, the committeemen also tried hard to keep each other accountable. Seattle ILA delegates, for example, were admonished by their peers and the Committee’s chair at least three different times for being “very boisterous and trying to corner the floor,”[18] or “once again flooding the Conference Meeting with over their limit of Delegates.”[19] Local 38-12 was probably more prone to committing these infractions since the committee consistently met in Seattle (where the Northern ILA District office was located), but other individuals reprimanded as well. For instance, Jack Bjorkland, the ILA Pacific District Secretary, was asked to report to the Strike Committee at once to explain why the West Coast longshoremen hadn’t heard back from the Eastern or Gulf ports about respecting their picket lines with an embargo. Bjorkland quickly answered the Committee’s summons, and produced the telegram he had wired to the Atlantic and Gulf District ILA Locals.[20]

It should be noted that the Northwest Strike Committee evolved from being comprised solely of longshoremen to including voting representatives of other craft unions. All marine crafts were included in the Strike Committee’s meetings after June 9th, the Teamsters were invited to participate on June 22nd, and even a representative from the Seattle Cereal Workers, who had requested the longshoremen help them in making the Fisher Flour Company 100% union, was given a vote on June 22nd. [21] Despite the gesture, though, the longshoremen and seamen eventually decided that they didn’t have the capacity to assist the cereal workers in their struggle, as “the present time wasn’t quite right to be involved…in more trouble.”[22] Lastly, the Northwest Strike Committee also coordinated its activities with other ILA locals on the West Coast by exchanging delegates with the Joint Marine Strike Committee in San Francisco, and accepting representatives from the San Pedro Local near Los Angeles.[23]

Evaluating the Northwest Strike Committee’s minutes

As a source, the records of the Northwest Strike Committee are important because they provide the fullest chronological account of the ’34 Strike in Seattle that this author has found, and they comprise the main primary material used in this study. Because of the extensive use of Committee minutes, it is useful to discuss both the usefulness and the limitations of these records. The most obvious problems with the Northwest Strike Committee meeting minutes are their insufficiency to address the early days of the strike and their potential bias and more carefully managed nature as public, not private, documents. It is easy to observe a gap in documentation between the start of the strike on May 9th and the formation of the Committee on May 24th. Similarly, there is an abrupt gap in the minutes between July 21st and September 13th, which occurs during the height of the longshoremen’s struggles.

Additionally, other problems with the committee’s records as a source are their public form, and possible pro-Tacoma bias. The minutes used in this study were not necessarily the private, internal records of the Strike Committee. According to Magden, two forms of minutes were kept by the committee, those records that were for more public consumption, and those that were private. When Magden’s Collection was first established at the University of Washington, archivists unknowingly missed preserving about half of Magden’s documents related to West Coast longshore history, including the private minutes of the Northwest Strike Committee, Local 38-12, and the Waterfront Employers Association.[24] What is unknown to this author however, is the extent to which the public minutes of the Strike Committee were significantly sanitized by the ILA. Certainly there are aspects of Committee debates and discussions that were somewhat vague in the public minutes, but these records also documented many useful events and kept various important pieces of correspondence, such as letters and telegrams, intact. Further research is required to assess the full limitations of these public minutes, which unfortunately falls outside the scope of this investigation at the present time.

The other aspect of the committee minutes that seems potentially suspect is the degree to which these records reflect a pro-Tacoma bias. The public minutes were recorded in 1934 by Ed Harris, the Committee’s permanent secretary, who was a leader of Tacoma’s Local and had close connections with Paddy Morris. According to Howard Kimeldorf, the Tacoma Local was “spared the radicalizing experience of employer resistance during the crucial years of union rebuilding,” and as a result of this, when “fifteen thousand West Coast dockworkers followed Bridges into the CIO to launch the ILWU in 1937, six hundred longshoremen in Tacoma and two smaller satellite ports were still firmly anchored to the conservative AFL and voted to remain behind with the ILA.”[25] This evidence, coupled with some hostility displayed by the Tacoma Local toward Seattle Local 38-12’s ability to keep Seattle’s port closed at the start of the ’34 Strike, suggests that perhaps the minutes of the committee are somewhat distorted by a Tacoma longshoremen’s point of view. This is a relatively minor point however, and too much is unclear for this author to be able to make any authoritative statements on the relationship between Tacoma and Seattle longshoremen. Indeed, the fact that the Northwest ILA Locals struggled together for 83 days undoubtedly did a lot to build strong bonds among Puget Sound longshoremen.

Tie-up of Alaskan commerce: the Pacific American Fisheries fleet

The Pacific American Fisheries problem that occupied the first meeting of the Northwest Strike Committee arose during meetings between ILA District negotiators and the employers in San Francisco. The Northwest was represented on this negotiating team by Paddy Morris, who was a veteran ILA leader. In addition to being a member of the negotiating team, Paddy Morris served as one of Tacoma’s delegates to the Northwest Strike Committee, and was a former member of the Seattle Local before he was fired after a strike in 1908. Described by Magden as someone who always confronted the employers head-on,[26] Morris presented the shipowners with a list of demands on May 24th. Specifically, the longshoremen demanded that employers bargain with the ILA according to the laws laid out in the NIRA, give control of the hiring halls to the union, arbitrate wages and pay workers retroactively, and settle the seamen’s strike before work resumed on the waterfront.[27] Employers were given a deadline of May 26th to respond. During negotiations the deadline, Paddy Morris called Ed Harris in Tacoma to inform him that the “Pacific American Fisheries shipments must be made at once,” as their lock-up in Seattle was “wrecking all mediation plans” in San Francisco.[28]

The Pacific American Fisheries shipments that Morris was referring to belonged to a corporation by the same name, a salmon-packing company based in Bellingham, Washington. Pacific American Fisheries, or PAF, operated canneries along the Pacific Coast that ranged from Alaska to Puget Sound. Over the years, PAF had come to depend on its Alaskan sites more, due to laws limiting the use of fish traps in Washington State.[29] When the longshoremen struck in 1934, PAF’s fleet was trapped in Seattle. Since Alaska’s summer salmon fishing season only offered PAF a small window in which to do business, the ILA’s closure of the Port of Seattle was a huge threat to the company’s profits. According to a historian named August Radke, the President of Pacific American Fisheries, Archie W. Shiels, said in mid-May of 1934 that his company’s “canneries in the Bristol Bay area [of Northern Alaska] would not run unless the shipping problem was solved.”[30]

The threat to Pacific American Fisheries’ business during the ’34 Strike was not an isolated case of one company. There were at least six other Alaskan shipping lines that had vessels tied up in Seattle by the longshoremen’s strike on May 26th, including the Alaska Steamship Company, the Northland Transportation Company, and Willis Navigation.[31] Because Seattle was the main continental U.S. port that shipped goods to Alaska, Morris and the other members of the ILA negotiating team were pressured to solve the “Starving Alaskans” problem quickly. In fact, the union negotiators in San Francisco had already taken action before the Northwest Strike Committee met. Morris told the committee in a telegram that the District had “made a pledge to the Government that the necessary Alaska work will be done,” as “the impression being broadcasted was that people were starving.”[32] The ILA’s refusal to work the Alaska cargo put them in danger of losing support from “Southern A.F. of L. Bodies, including the seamen, the fishermen, the teamsters and all the other various Locals” who had been sympathetic to the longshoremen.[33]

With port-to-port unity threatened, the Northwest Strike Committee had to find a way to solve the Alaskan problem. Eventually, the federal government began pressuring the Locals, and the Northwest Strike Committee agreed to “the loading of one ship for Southwestern Alaska,” as long as it carried “cargo of a needy nature” and was loaded and operated by “100 percent union men.”[34]

The Alaska Agreement

As stated earlier, the decision of the Northwest Strike Committee to release one ship with supplies from Seattle did not solve the ILA’s Alaska problem. On May 29th, John Troy, the Governor of Alaska, wrote a telegram to the Northwest Strike Committee which said:

We are right now entering what ought to be the busiest season of the year and bear in mind that the fish along the coast will not wait the outcomes of strikes nor will water needed by the miners continue to run. Alaska has only a few weeks in which to harvest her fish and gold and other products and to build roads and do public and private construction work before another winter time begins. It is not a question of bringing up food only…please cooperate with federal officials who are trying to restore shipping.[35]

In response, the Committee requested that Troy refer his correspondence “to the parties who are directly responsible for conditions embodied in your telegram—namely the WATERFRONT EMPLOYERS OF THE PACIFIC COAST” [original emphasis of the minutes are used from this point on].[36] Meanwhile, the ILA tried to buy more time by passing a motion to “work no ships (WITH THE EXCEPTION OF GOVERNMENT SHIPS) for a period of one week.”[37] Exactly a week later, representatives of the Alaska Pacific Salmon Company visited the Strike Committee to ask the ILA if they could “charter ship for the hauling of cannery supplies to Alaska.”[38] The longshoremen asked the company representatives if they were “willing to pay $1.00 straight time and $1.50 overtime.” They were, and this breaking of ranks by a shipping company pressured other employers to meet the union’s demands.[39]

At two in the afternoon that same day, Seattle’s newly elected mayor, Charles Smith, asked the Northwest Strike Committee to meet in his office with the Alaska shipowners to discuss a settlement. According to the ILA’s meeting minutes, Mayor Smith was “being rather insistent upon the immediate release” of the Alaskan ships, threatening that “these ships would be loaded or else.” The Alaska employers “acceded to wage increases and union-shop demands,” but the Alaska Steamship Company insisted on the Seattle Local taking in 70 or 80 scab workers from the fink hall.[40] This was initially not at all satisfactory to the Committee. The company held out on this demand, but Paddy Morris managed to get them to “agree that 30 days after the settlement of our Strike…these men’s applications would be acted upon” in good faith by Local 38-12.[41]

The insistence of Alaska Steam to keep their fink halls sparked a controversy over whether Seattle’s delegates had the power to act without consulting their rank and file.[42] The Seattle committeemen believed that Local 38-12’s rank and file couldn’t swallow working with men who had crossed their picket line, and they asked the entire Strike Committee to attend their union’s meeting later that night.[43] When “the clause relative to the 85 finks” was brought up during 38-12’s rank-and-file meeting, it “caused an awful wave of hostility” among the 2,000 members present.[44] The situation was only resolved after the longshoremen’s International President, Joseph Ryan, who had come from New York to help settle the strike, spoke on the issue. When Ryan first took the floor, “the meeting was almost in an uproar.” But after giving a three-hour talk on the question, two votes by voice and hand were close in granting Seattle’s delegates the authority to agree to accept Alaska Steam’s finks into the Local in the future. After another “lengthy talk,” the meeting got “back to a more normal, easy frame of mind.” When the motion to “give delegates Full Power to Act” was called, it carried almost unanimously.[45]

The next day, Paddy Morris read the finalized Alaska Agreement to the Strike Committee. The proposed agreement bound the Alaska employers to hiring only “members of the I.L.A. for all their longshoring, stevedoring and checking” jobs, allow men to be “dispatched by the local I.L.A. hall” alone, and only hire seamen “under terms that are satisfactory to their respective organization with the A.F. of L.”[46] Then, the Strike Committee decided to send a letter to all Northwest ILA Locals detailing the points of the Alaska Agreement.[47] The letter also explained why the Strike Committee had signed the agreement, pointing out that “Terrific pressure was brought to bear on the Public to incense them against the Longshoremen” and that “the Waterfront Employers Union was bitterly opposed to the release” of the Alaskan ships.[48] By taking the initiative to negotiate an agreement, the longshoremen argued that they “demonstrated to the Public that… [they were] not responsible for the continuation of the strike.”[49] If these considerations didn’t fully convince the Northwest’s rank and file, the deal was sweetened by the fact that the Strike Committee announced the creation of an Emergency Relief Fund for strikers and their families.

The committee decided that each longshoreman working Alaskan ships in the future would be required to allocate a portion of their wages into this Relief Fund for the benefit of all Northwest ILA Locals. On top of this, even though Seattle was the main port working Alaskan cargo, the Committee voted to distribute work among more locals. Specifically, out of every eleven gangs working under the agreement, five would be supplied by Seattle, three by Tacoma, two by Everett, and one from Olympia.[50] Yet when all the points of contention surrounding the Alaska Agreement seemed to be resolved, and the ILA was ready to sign on the dotted line, a new threat emerged to challenge the fragile solidarity that had been built by maritime workers in the last month.

Toward the end of the May 8th meeting of the Northwest Strike Committee, a delegation of representatives from the International Seamen’s Union (ISU) informed the longshoremen “that they were refusing to sign the Alaska Pact relative to their men, on account of wages.”[51] In the “satisfactory terms”[52] clause of the Alaska Agreement relating to seamen, the employers offered the ISU $55.00 straight time per month and 50¢ overtime, but the sailors wanted $62.50 per month straight time and 60¢ overtime.[53] The crisis was averted when the seamen decided that “rather than tie [the longshoremen] up,” they would leave their wage demands to arbitration. The ISU’s solidarity with the longshoremen was rewarded later in the meeting when a phone call came for them from the employers, who were offering the seamen a raise of $5 per month and 60¢ overtime per hour. After hearing this, ISU delegates “seemed a bit more satisfied and stated that they would all sign.”[54] On June 9th, the Alaska Agreement was ratified, and the ILA established an important precedent on the docks by forcing a division within the ranks of the waterfront employers and strong arming a handful of shipowners to give into almost all the union’s demands.

Failed Negotiations

While the Northwest Strike Committee was preoccupied by negotiations concerning the Alaska Agreement, there were two main agreements from San Francisco proposing settlements to the strike. On May 24th, the ILA District negotiating team, of which Paddy Morris was a member, proposed an end to the strike if the employers would agree to a coastwise settlement, give control of the hiring halls to the union, submit wage disputes to arbitration, and address the seamen’s grievances before the longshoremen went back to work.[55] In a meeting with the employers on May 25th, Paddy Morris reported to the Northwest Strike Committee that negotiations “were deadlocked on the question of hiring halls—looks like a finish fight.”[56]

On May 28th, the employers offered the ILA a counterproposal which would accept the union as the representative of longshoremen for collective bargaining and create jointly managed hiring halls at each port, with the registration and dispatching of men falling under the responsibility of the employers.[57] The ILA District negotiators walked out of this meeting, but the situation was complicated by the presence in San Francisco of the longshoremen union’s International President, Joseph Ryan. Described by the historian Charles Larrowe as an old-style AFL leader who viewed craft unionism as dogma, Joe Ryan was not well qualified to work with West Coast longshoremen organizing around industrial unionist goals.[58] Ryan’s support of the employers’ May 28th proposal, along with his failure to understand why the Pacific District ILA hated the fink halls and insisted on coastwise recognition, [59] earned him the animosity of most of the West Coast’s rank and file.

Although the May 28th agreement was never signed, the San Francisco ILA spurned it wholesale, and admonished Ryan’s conciliatory approach with the employers. Unaware of the West Coast longshoremen’s newly forged coastwise solidarity, Ryan went to sell the May 28th proposal to different ILA Locals in the Pacific Northwest. When Ryan went to a meeting of the Northwest Strike Committee in Tacoma, the May 28th proposal was rebuffed by the delegates, and the Committee unanimously went on record rejecting “any and all proposals which do not recognize our original demands—AND THAT WE REJECT THE EMPLOYER’S PROPOSITION AS A WHOLE.”[60] In Seattle, the local voted down the May 28th proposal with “a deafening roar.” [61] Dewey Bennett, Local 38-12’s secretary, said it best: “We’ll stick with every local on the coast. One union agrees—all unions agree. That’s our policy.”[62]

Assistant Secretary of Labor, Edward McGrady, was sent to the West Coast by Frances Perkins in May to try his hand at managing the strike. After failing in his first attempt to end the conflict in San Francisco, McGrady came up with a new plan on June 5th. This solution proposed a “triple alliance” between the government, the ILA, and the employers to manage the hiring halls.[63] The plan called for the Federal Employment Service to help run the hiring halls and dispatch longshoremen, but was rejected by both the ILA and the waterfront employers.[64]

After the federal government and the longshoremen’s International President failed to bring about settlements to the strike, employers pushed local mayors to either bring an end to the dispute or do something to protect scabs on the docks.[65] On June 12th, Charles “Tear Gas” Smith, Seattle’s mayor, said to the newspapers that “if an agreement [to the strike] is not announced by 1 P.M. Thursday,” he would “take definite steps to relieve the people of Seattle from the burden of this costly controversy.”[66] Mayor Smith visited a meeting of the Northwest Strike Committee later that afternoon, and “was very emphatic about the opening of the Port.”[67] Smith’s “manner of address did not appeal to the Delegates, and his animosity towards ONLY the Longshoremen, instead of may be laying a little blame upon the Employers for the continuance of the Strike” did not help matters further.[68] The mayor asked for a committee of three ILA members with full powers to act on behalf of the rank and file to meet with him and the employers to negotiate a settlement to the strike. The Strike Committee adopted the Alaska Agreement as their “Model for any future negotiation…as it seemed satisfactory to the Alaska Shippers,” and then chose three Seattle delegates—George Clark, Robert Collins, and William Craft—to meet with the mayor. Later that evening, Clark, Collins, and Craft reported back to the Strike Committee that “the Employers had rejected our Plan to settle the strike on a Coastwise Basis, with some plan similar to the Alaska Pact.” Instead, the waterfront employers handed the Seattle delegates the May 28th plan as a counter-proposal, which the Strike Committee again rejected.[69] With the longshoremen refusing to back down, the waterfront employers moved to protect their strikebreakers by force.

Opening Seattle’s Port

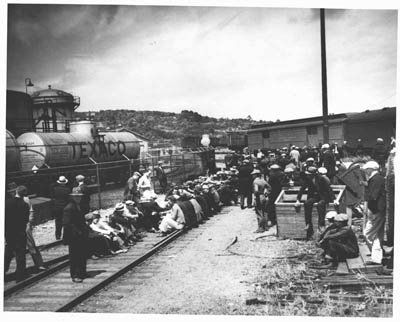

Greasing The Rails At Smith Cove

Greasing The Rails At Smith Cove

Longshoremen and Seaman at Smith Cove grease the rails to prevent rail engineers from taking cargo from the waterfront.

(Ronald Magden Collection).

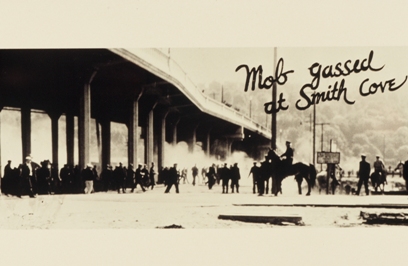

Police Dispersing Longshore Pickets At Smith Cove - 1934 Strike Police move to disperse longshoremen and seamen during the Battle of Smith Cove (Magden Collection)

Police Dispersing Longshore Pickets At Smith Cove - 1934 Strike Police move to disperse longshoremen and seamen during the Battle of Smith Cove (Magden Collection)

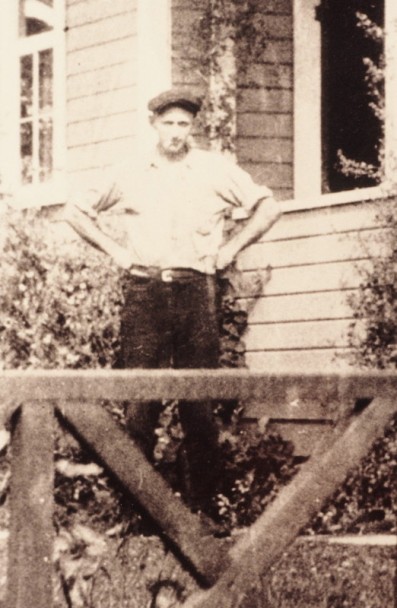

Wayne Moisio, the "Train Stopper" (Magden Collection).

Longshoreman arrested for trespassing at Smith Cove (Local 23 Collection).

After his deadline passed on June 14th, Mayor Smith declared a state of emergency. The mayor had 500 new riot clubs made for the police department, and the waterfront employers augmented Smith’s ranks with a private security force.[70] After a tense standoff between the police and longshoremen, Smith decided to forcibly open the port on June 20th. Over 300 police and deputy sheriffs were massed at Smith Cove near Pier 40 (near today’s Magnolia Bridge and Pier 90), armed with pistols, riot clubs, sawed-off shotguns, and tear gas.[71] Included in their ranks were twenty mounted police. Under police protection, 100 scabs began unloading cargo from ships docked at Pier 40.

On June 21st, 600 union members formed pickets facing off against the police at Smith Cove. When the longshoremen saw that the employers were trying to take cargo away from the docks on trains, union members greased the tracks. Tensions escalated, and Smith ordered his mounted police to remove the longshoremen interfering with the trains. Dockworker Wayne Moisio, who got his nickname of “Train-Stopper” at Smith Cove, recalled:

We all sat on the railroad tracks where the train was supposed to come in. Well, the first ten may be pushed out, but they couldn’t get us all. The mounted police opened the track, but as soon as they left, we went back and sat on the track. Anyway, the train engineer decided not to go on the track. So he went on another track trying to go out. Somebody threw a good-sized rock through the cab window and almost hit the engineer.[72]

After the rock was thrown at the locomotive, the longshoremen climbed aboard and convinced the rail engineer to turn back in respect for their pickets.[73] With railworkers and Teamsters refusing to take cargo away from Smith Cove, the employers’ scabs could only fill warehouses by the docks, and in this way, the ILA managed to keep the port from functioning by manning pickets at Smith Cove from the end of June into July. Burt Nelson recalls that many strikers were arrested, and gave this description:

Most of those arrested were in situations provoked by the police. It was a bad enough situation that I was prompted to stand on a fire hydrant on the water side of the access area between [Pier] 90 and 91. They would bring troops out there every afternoon from Pier 90 and line them up in two ranks. I would stand on the fire hydrant and read them the Bill of Rights. The commander would swear, but none of them ever tried to put their hands on me…There was always a big crowd that would applaud, hoot and holler at the cops. The only thing that is still there is the viaduct… During that same period of time at night nothing stirred. I don’t know who got it started, but we would all applaud in unison. Apparently the cops thought there was a meeting and they would march out 4 abreast. Nothing happened. Not a picket in sight. We’d be back under the bridge. So they’d go back in and we’d applaud again. They never came back the second time. They’d go back in after standing around for an hour on the black top.[74]

The ILA’s constant picketing achieved results and also relied on solidarity from other workers, including the seamen.

Jack Mahoney was a member of the Sailors Union of the Pacific, and first went to sea for Alaska Steam in 1929. According to Mahoney, the Seattle seamen would “rent 3 trucks…clean…the hall out and hauled us out to Smith Cove… We always had men there.”[75] Jack was very active in the strike, and even posed as a scab to gather intelligence on what the employers were up to at Smith Cove. He says that one day

The shipowners called me at home and wanted to know if I would go on a ship. We wanted information about where I could get on a ship. They told me that if I would go down to the Seattle Bus Terminal that they would have a car there to pick me and others up and take us aboard the ship. I said, ‘Fine.’ I told my Dad and he told me to get right down to the hall and acquaint them with that…The company had asked me to put on dress clothes so I wouldn’t look like a seaman. There were several of us to go to the bus terminal, but I was to go inside and get the others to come out. I walked into the terminal and told some guys with seabags to go to a spot where the car would be. I saw one guy who I had been shipmates with. The minute he saw me he started to run. I caught him just as he got to the end of the bus terminal. He turned around and put up a fight so I belted him. That no more happened than a policeman grabbed a hold of me…As we went out I pulled away from his hand on my sleeve and down the street I went… In the meantime the guys couldn’t wait for me to come out with the scabs, so they came in and there was quite a melee right there in the terminal. They dumped them. Surprisingly, the employers called a second time and I told them there was nothing but trouble when I arrived at the bus terminal. They said they wanted me to go to Pacific Steam Company where they had arranged to take me by boat to Smith’s Cove. I went right back to the hall and we put a boat on patrol. First time we had one on picket duty. We stopped them. They couldn’t get men through there either. The President Grant was the only ship that made it out of Seattle during the ’34 Strike.[76]

As a result of sustained vigilance around town and a constant presence at Smith Cove, the ILA reached an acceptable status quo—the employers were sometimes able to move goods into Piers 40 and 41 via trains, and get strikebreakers to load cargoes, but this was by no means an easy feat. In solidarity, seamen also prevented ships from sailing out of the harbor (or taught scabs this wasn’t a good idea), further foiling employer’s plans.

The ILA takes the offensive: Reneging on the Alaska Agreement

ILA member Shelvy Daffron became the first casualty of the the 1934 strike, shot in the back by guards at Smith Cove. He is pictured here a week before he died (Local 23 Collection).

Later on the evening of June 21st, the Northwest Strike Committee met and decided to use the Alaska Agreement to punish the mayor. The ILA had agreed to sign the Alaska Agreement because Smith had given his word “that at least the City Administration would remain neutral” during their struggle with the employers, now rendered false because of the police presence at Smith Cove.[77] The Strike Committee appointed delegates to meet with the mayor about his use of police on the docks. Reporting back to the Committee, the delegates said they “had a very hot session with the Mayor, but he would absolutely not remove his police from [the] docks.”[78] As a result, a motion to “pull men from Alaska Ships at once” was immediately passed, and the Strike Committee sent the following telegram to Northwest ILA Locals:

Mayor Smith breaks faith and spirit of Alaska agreement by placing armed police on docks when no lives or property were at stake, there being no scabs or pickets on said docks—N. West Strike Committee has ordered work ceased on all Alaska ships at once this includes all Marine Groups—Employers making no progress— Morale good.[79]

At the same time that the Northwest Strike Committee was meeting, members of Local 38-12 went to the Seattle Central Labor Council and asked for organized labor to “go on record favoring a general strike if police and armed guards were not withdrawn [from the waterfront] in twenty-four hours.”[80] Conservative labor leaders influenced by Teamsters’ conservative leader Dave Beck tabled this request, but the Council did pass a vote demanding that Smith remove the police, or organized labor would consider initiating a recall movement.[81]

Once the Northwest Strike Committee cancelled the Alaska Agreement, the Alaska Steamship company threatened to sue the ILA “for any loss or delay caused by [the longshoremen’s] stoppage of work.”[82] Paddy Morris succeeded in calming down Alaska Steam, and they agreed that “they would try and get the Police and guards removed from the Docks” so the longshoremen could work their ships again.

June 30th claimed the first Seattle casualty of the ’34 Longshore Strike when Shelvy Daffron, a member of Local 38-12 and delegate to the Northwest Strike Committee was killed. Daffron, who earlier in the day had alerted the Strike Committee about unrest at Smith Cove, traveled in the evening to Point Wells, where the union had heard that scab crews were about to take two oil tankers out of the port. When the longshoremen tried to get past the dock’s gates, they were ambushed by guards and Daffron was shot in the back.[83]

As longshoremen were distracted by the death of Daffron the question of working Alaskan cargo, the employers began sending more ships to Smith Cove. In the first week of July, an estimated 200 scabs were working under police protection at Piers 40 and 41, and trains started penetrating pickets to reach the dockyards.[84] With government representatives like Colonel Ohlsen of the Department of the Interior warning the ILA that the longshoremen would have to work Alaskan ships or troops would load them instead, an immediate concern of the Northwest Strike Committee became finding a way to work Alaskan ships while also keeping the Port of Seattle closed.[85] The ILA decided to maximize its resources and shift Alaska work to a different port, leaving longshoremen in Seattle free to focus on the problems at Smith Cove. The Strike Committee chose to work Alaska ships out of the Port of Tacoma after Shelvy Daffron’s funeral on July 6th.[86]

The Battle of Smith Cove

Longshoreman's picket line at Garfield Bridge shortly before police began using tear gas to clear the strikers (Local 23 Collection)

Under orders from Seattle Mayor Charles Smith, police used tear gar to clear strikers from Smith Cove (Local 23 Collection)

Strikers gassed at Smith Cove (LOcal 23 collection)

News crews on a railcar during the Battle of Smith Cove (Magden Collection).

Mounted Police chase strikers towards waiting paddy wagons during the final stages of the Battle of Smith Cove. Forty to fifty strikers were arrested (Magden Collection).

Ten days later, the waterfront employers hired more strikebreakers to work at Smith Cove, and on July 18th, the Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, and Bellingham ILA Locals formed “flying squads” composed of their most disciplined members. With 1,200 strikers organized into these crack units, longshoremen attacked the police at Piers 40 and 41. This was the start of the “Battle of Smith Cove,” and when the longshoremen made their first advance against the police, they were stopped by tear gas. The strikers made a second charge, this time covering their faces to mitigate the gas, and managed to break through police lines, camping overnight by the railroad tracks near the docks. The next day, a second contingent of longshoremen met with the flying squads, and Mayor Smith personally ordered the police to clear the ILA out of Smith Cove. Tear gas was again used to immobilize the strikers, and mounted police chased the longshoremen away from the docks. In the ensuing rout, police clubbed strikers who held their ground.[87]

Many longshoremen remember the Battle of Smith Cove, and their stories deserve to be quoted at length. According to Burt Nelson,

The horse cops were after...Huey Reynolds, who was a big raw-boned man, a tough operator, the horse cops beat him rather badly, broke his arm and cut his head up…The cop stood in his stirrups…turned his horse around and rode away after somebody else… The horses came through…and split us at the railroad tracks. Some of us went South and some went out into Elliot Avenue and the horses stopped there for the time being. These guys ran us clear out to Galer and we were trying to get back to the main bunch. Then they rode us down over the bank just like a cavalry charge. All of these cops had tear gas masks on. They ran us up into the trees as far as they could ride the horses. I lay up there half the afternoon coughing and trying to get rid of that tear gas. Made you sick as hell… This cop on the horse was after me personally. I had made eye contact with him earlier when I was reading the Bill of Rights on a fire hydrant. He thought he was Custer at the Little Big Horn with white horse and all.[88]

According to Jack Mahoney, “Machine Gun Smith” ordered the new police chief to mount machine guns at Pier 91. Mahoney says that “the police chief…told the mayor…they were able to take care of things as they were, and…didn’t need any machine guns or emplacements,” but Smith insisted, and so the chief handed over his badge and said “You get someone else to do your scabherdin.”[89] Wayne Moisio remembered the tear gas most, and learning some tricks from an older Wobbly:

When they gassed us down at Pier 41 one old Finlander had on thick leather gloves. I looked at him and wondered why he had those on. We were down below by the railroad tracks. The police were up on top throwing canisters at us. As soon as the tear gas canister hit, he would grab and throw them back. The cops got the gas. I didn’t know that as soon as the canister got hot, they’d explode, but this old Wobbly sure knew. He had learned what to do when he had been in the mines.[90]

Finally, Buck Wiley said that while Smith’s forces “were well organized…a lot of the mounted police were drunk.” Wiley’s story is perhaps the best indication of how frightening the longshoremen’s militant solidarity was to the police. Indeed, although the maritime workers were eventually cleared out of Smith Cove by the police, they kept on coming back, and their persistence coupled with their sustained coastwise solidarity, was beginning to take its toll on the waterfront employers.

The End of the Strike

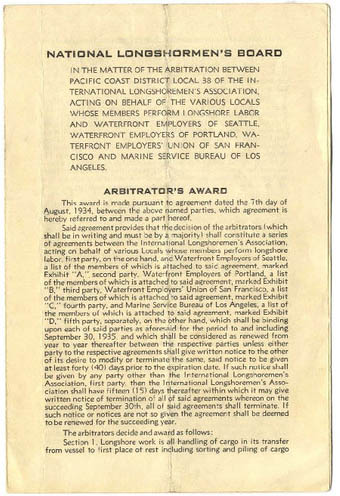

National Longshore Board ruling

The final arbitration award, handed down by President Roosevelt's National Longshore board on August 7, 1934. Click on the image to download a .pdf copy of the document, courtesy of the ILWU archive.

The first dispatch from the union-controlled hiring hall after the 1934 strike (Local 23 collection).

Longshoremen return to work, September 15, 1934.

Veterans of the 1934 strike gather at Smith Cove in 1990 (Magden collection).

While the Northwest longshoremen were busy keeping Seattle closed and dealing with the Alaska shippers, events in San Francisco would bring about the end of the Great 1934 Longshore Strike. When the San Francisco Local refused to accept a mid-June settlement proposal, the waterfront employers decided to open the biggest port on the West Coast by force. On July 3rd, 700 police tried to protect scabs from picket lines, but violence erupted and “the waterfront became a vast triangle of fighting men.”[91] Two days later, a train was moving two boxcars towards Matson’s docks for scabs to handle at Pier 30. Over 3,000 pickets watched the engine approach, and when police tried to clear them away from the tracks, the longshoremen stood their ground and fought. The police were forced back by the strikers’ rocks, and the longshoremen surrounded the train and set it on fire.[92] When the strikers gathered back at their union hall around noon, the police, “viewing any crowd as a potential danger…execute[d] a pincers movement against the…strikers,” who were trapped between streets.[93] Two men—Howard Sperry, a member of San Francisco’s ILA Local, and Nick Bordoise, a Communist Party member—were shot and killed by panicky police officers in the resulting fray, memorializing July 5th as “Bloody Thursday” in the memory of West Coast longshoremen.[94]

The San Francisco ILA commemorated the deaths of Sperry and Bordoise on July 9th by holding a huge funeral procession that engulfed both ends of Market Street in downtown San Francisco. According to Bruce Nelson, this demonstration acted to “crystallize sentiment for a general strike” among the public and organized labor.[95] A week later, a general sympathy strike was observed by almost every union in San Francisco. Yet the longshoremen found themselves excluded from a leadership role in the general strike by conservative AFL leaders, and as a result of this, the massive revolt of labor didn’t last more than four days.[96] Two days after the end of the general strike on July 22nd, the San Francisco Teamsters voted 1,138 to 283 to return to work, severely undermining the overall position of the ILA.[97]

Although the longshoremen were in a much weaker position without the help of the Teamsters, the length of the strike had finally taken its effect on the waterfront employers. In the first month of the 1934 Strike, the clampdown on coastal shipping had cost the waterfront employers an estimated $45 million. In addition to losing revenue, the employers’ expenses increased, since paying for scabs’ wages, protection, and housing was expensive. Even in San Pedro, which was partially open during most of the strike and where the employers’ strike-breaking strategy was most effective, scab labor still cost local shippers as much as $7,000 per day, and this was a high price to pay for a port that wasn’t functioning at full capacity.[98]

What finally toppled the employers’ resolve however, was intervention by the Roosevelt Administration. According to labor historian Ottilie Markholt, “the spectacle of employers defying New Deal promises to labor” pressured the government to act to end the strike.[99] This was achieved when President Roosevelt authorized the U.S. Postmaster General to review the government’s waterborne mail contracts with the shippers. If these contracts were cut for the six biggest shipping lines, the employers would have lost an estimated $23 million in subsidies.[100] As a result of this government threat, the employers agreed to government arbitration of all issues in the strike—including control over the hiring halls and negotiations with the seamen—if the ILA would agree to the same policy for their demands. Having been out of work for over two months, rank-and-file longshoremen “were almost broke, and had reached the end of their rope,” making total arbitration seem more palatable than it had been at the beginning of the strike.[101] Additionally, it’s possible that some ILA members viewed their situation as historian Jonathon Dembo does, who argued that the employers’ concessions in submitting all issues to arbitration, “made acquiescence in labor’s demands inevitable.”[102]

Sensing the longshoremen’s exhaustion, Roosevelt’s National Longshoremen’s Board asked the ILA to survey the Pacific District on whether rank-and-file members wanted to submit all strike demands to government arbitration. The ILA agreed and sent out coastwise ballots on July 21st. The final results of this vote revealed 6,504 longshoremen favoring total arbitration to a 1,525-man opposition; in Seattle alone, the vote was 762 for arbitration and 103 against.[103] West Coast longshoremen went back to work on July 31st, and the final chapter of the Great Longshore Strike of 1934 was closed when Roosevelt’s Arbitration Board decided to give the ILA control over hiring hall dispatching, among other concessions, on October 12th. The ability of the ILA to control dispatching ended up eliminating the discrimination union longshoremen had previously faced in the fink halls, and corrected the disparity of the waterfront’s distribution of power in favor of organized labor.

Selected Bibliography

Dembo, Jonathon. Unions and Politics in Washington State: Garland (1983).

Egan, Michael. That’s Why Organizing Was So Good: Reed College Thesis (1975).

Foisie, Frank. Decasualizing Longshore Labor and the Seattle Experience: Waterfront Employers of Seattle (1934).

Frank, Dana. Purchasing Power: Cambridge (1994).

Garnel, Donald. The Rise of Teamster Power in the West: California (1972).

Kimeldorf, Howard. Reds or Rackets?: Berkeley (1988).

Larrowe, Charles. Harry Bridges: The Rise and Fall of Radical Labor in the US: Lawrence Hill and Co. (1972).

Larrowe, Charles. The Great Maritime Strike of ’34: Part I, Labor History: Vol. XI, No. 4 (1970).

Larrowe, Charles. The Great Maritime Strike of ’34: Part II, Labor History: Vol. XII, No. 1 (1971).

Magden, Ronald. A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers: ILWU 19 (1991).

Magden, Ronald. Papers: University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1.

Markholt, Ottilie. Maritime Solidarity: Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee (1988).

Nelson, Bruce. Divided We Stand: Princeton (2002).

Nelson, Bruce. Workers on the Waterfront: Illini Books (1990).

Radke, August. Pacific American Fisheries, Inc.: McFarland & Company (2002).

Schmidt, Henry. Secondary Leadership in the ILWU 1933-1966: Berkeley (1983).

Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States: HarperPerennial (1990).

[1] quoted in Bruce Nelson, Workers on the Waterfront (Illini Books, 1990), p.129.

[2] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.207.

[3] For the endorsement, see Dembo, p.575.

[4] Jonathon Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State (Garland, 1983), & Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.207.

[5] Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, February 7th, 2008 Note: to the author’s knowledge these riots are not covered in Magden’s works, and the date that they occurred is currently unknown.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.208.

[8] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.102

[9] Interview with Ron Magden by Rod Palmquist, January 30th, 2008.

[10] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, May 24th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.1.

[11] Ronald Magden, The 1934 West Coast Longshore Strike, University of Washington Special Collections, Videorecord SPE-251.

[12] Interview with Burt Nelson by Ronald Magden, April 21st, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 3.

[13] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 7th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.1.

[14] Ibid., p.2.

[15] For example, see minutes of May 29th, 1934, p.5, June 8th, 1934, p.1, & June 14th, 1934, p.3, Northwest Strike Committee, June 7th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6.

[16] The use of parliamentary procedure can be found any meeting, but for the committee’s specific rules, see May 25th & 26th minutes, p.2. For voting strength and an example roll call, see NWJSC minutes of May 25th & 26th, 1934, for a quorum call, see minutes of September 13th, 1934. Northwest Strike Committee, June 7th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6.

[17] For an example of a proxy transfer, see minutes of June 12th, 1934, p.1.

[18] Paraphrased, Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 30th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.3.

[19] Minutes of July 6th, 1934, p.2, for another example, see minutes of June 20th, 1934, p.1, Northwest Strike Committee, June 7th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6.

[20] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, July 20th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, pp. 1-2.

[21] For the Marine groups, see minutes of July 9th, p.3. For the Teamster invitation see minutes of June 22nd, 1934, p.1. For the Cereal Workers, see minutes of June 21st, 1934, p.1. For an example of a meeting with lots of allied-craft delegates in attendance, see minutes of July 9th, 1934, p.1. Northwest Strike Committee, June 7th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6.

[22] Paraphrased from minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 8th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.1.

[23] For exchanges with the Joint Marine Strike Committee, see minutes of June 14th, 1934, p.1; and minutes of June 22nd, 1934, p.3. For an example of interaction with San Pedro, see minutes of June 12th, 1934, p.1, Northwest Strike Committee, June 7th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6.

[24] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007.

[25] Paraphrased in Howard Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets? (Berkeley 1988), p.76.

[26] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007.

[27] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.104.

[28] Transcript of phone call between Paddy Morris and Ed Harris, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6.

[29] August Radke, Pacific American Fisheries, Inc. (McFarland & Company, 2002), pp.131-135.

[30] Ibid., p.151.

[31] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, May 25th & 26th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.6.

[32] Paraphrased from telegram, minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, May 24th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.3.

[33] Transcript of phone call between Paddy Morris and Ed Harris, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6.

[34] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, May 25th & 26th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.6.

[35] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, May 29th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.3.

[36] Original emphasis, minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, May 29th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.6.

[37] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, May 29th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.7.

[38] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 5th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.2.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid., p.3.

[41] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 7th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.1.

[42] Ronald Magden, The 1934 West Coast Longshore Strike, University of Washington Special Collections, Videorecord SPE-251.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 7th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, pp.2-3.

[45] Ibid., p.3.

[46] Copy of Alaska Agreement, minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 9th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, pp.1-2.

[47] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 8th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.1.

[48] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 9th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.3.

[49] Ibid.

[50] See minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 8th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, 1934, pp.1-3.

[51] Ibid., p.4.

[52] Ronald Magden, The 1934 West Coast Longshore Strike, University of Washington Special Collections, Videorecord SPE-251.

[53] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 8th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.4.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.104.

[56] Telegram in minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, May 25th & 26th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, 1934, p.6.

[57] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, May 29th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.2.

[58] Charles Larrowe, “The Great Maritime Strike of ’34: Part I,” Labor History, Vol. XI, No. 4 (1970), pp.436-438.

[59] see Charles Larrowe, “The Great Maritime Strike of ’34: Part I,” Labor History, Vol. XI, No. 4 (1970), p. 438; and Jonathon Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State (Garland, 1983), p.576.

[60] Original emphasis, minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, May 29th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, 1934, p.3.

[61] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.211.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Jonathon Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State (Garland, 1983), p.577; and minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 6th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.7.

[64] Jonathon Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State (Garland, 1983), p.577.

[65] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.113.

[66] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 12th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.2.

[67] Ibid., p.3.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Ibid., pp.3-4, see also Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), pp.213-214.

[70] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.118.

[71] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), pp.218-19; and Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.119.

[72] Interview with Wayne Moisio by Ronald Magden, April 2nd, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 11.

[73] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), pp.219-220.

[74] Interview with Burt Nelson by Ronald Magden, January 22nd, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 1.

[75] Interview with Jack Mahoney by Ronald Magden, July 21st 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 9.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 21st, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.1.

[78] Ibid., p.3.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.219.

[81] Jonathon Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State (Garland, 1983), p.580; and Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.219.

[82] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 22nd, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6, p.2.

[83] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.221.

[84] Ibid., p.223.

[85] Minutes of Northwest Strike Committee, June 30th, 1934, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 1, Folder 6.

[86] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.222.

[87] Ibid., p.230-1.

[88] Interview with Burt Nelson by Ronald Magden, April 28th, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 3.

[89] Interview with Jack Mahoney by Ronald Magden, July 21st, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 9.

[90] Interview with Wayne Moisio by Ronald Magden, April 2nd, 1987, Ronald Magden Collection, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc #5185-1, Box 5, Folder 11.

[91] Bruce Nelson, Workers on the Waterfront (Illini Books, 1990), p.128.

[92] Charles Larrowe, “The Great Maritime Strike of ’34: Part I,” Labor History, Vol. XII, No. 1 (1971), p.8.

[93] Ibid., p.10.

[94] Ibid., pp.11-12.

[95] Paraphrased from Bruce Nelson, Workers on the Waterfront (Illini Books, 1990), p.128.

[96] Ibid., pp.128-9.

[97] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.178.

[98] Howard Kimeldorf, Reds or Rackets? (Berkeley 1988), p.61.

[99] Ottilie Markholt, Maritime Solidarity (Pacific Coast Maritime History Committee, 1988), p.191.

[100] Ibid.

[101] Phone Interview with Ronald Magden by Rod Palmquist, December 5th, 2007.

[102] Jonathon Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington State (Garland, 1983),p.581.

[103] Ronald Magden, A History of Seattle Waterfront Workers (ILWU 19, 1991), p.231.