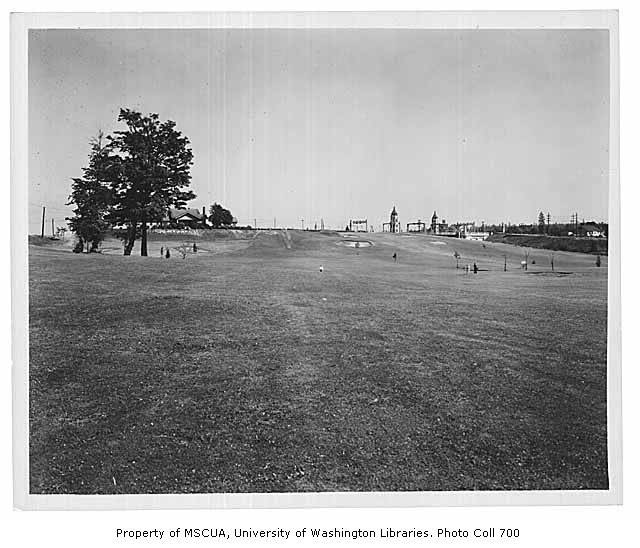

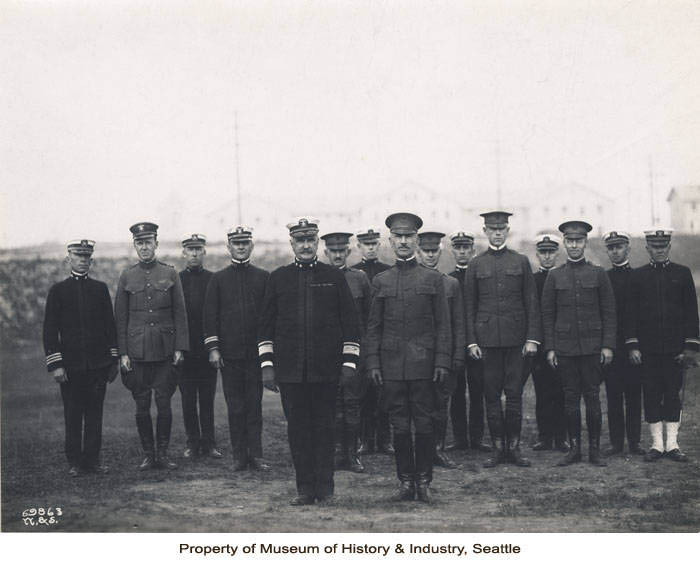

After World War I broke out in 1914, the United States Navy built a training camp on the banks of the ship canal in the spot Winkenwerder proposed the Arboretum be planted. In order to build the facilities, a large swath of the campus was cleared. When the war ended, the Navy turned the area back over to the University. With the land cleared, the area seemed optimal for planting trees. Plans were made to establish the Arboretum on the vacated land.

However, other parties had ideas for the Navy’s old training grounds. Golf enthusiasts on campus and in the community prevented development of the Arboretum in that space. Golf course advocates reasoned that fairways and putting greens could coexist with the needs of an arboretum. Their appeals convinced the University’s new President Henry Suzzallo. In late 1923, the University’s College of Forestry Dean Hugo Winkenwerder, an early champion of the Arboretum, and one of the primary university forces behind its establishment, indicated that he “lost all hope of ever developing an arboretum on the University campus.”

Winkenwerder’s lost hopes did not destroy his goals of developing an arboretum to serve the University somewhere. He met with President Suzzallo to discuss options for developing an arboretum. Though Suzzallo was responsible for the decision that allowed the golf course to be developed instead of an arboretum, Winkenwerder was able to convince the president that an arboretum would be an important addition to the University.

Shortly thereafter, Suzzallo became a proponent of the establishment of an arboretum near campus. In the mid-1920s, he engaged in a series of talks with business and professional organizations to drum up support for the campus arboretum. In a speech to the Seattle Rotary Club he said, “The time is ripe for fostering the idea of a great botanical garden…. One great undeveloped park remains—Washington Park with its undeveloped north portion reclaimed from the lake. In our system of specialized parks it should be a Botanical Garden which will express Seattle’s unique qualities more than others.” Suzzallo recognized that Seattle’s climate would permit far greater diversity of plant species than at the other two great botanical gardens in the United States at the time, the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis and the Arnold Arboretum near Boston. He claimed, “Our botanical garden can become the greatest in the world.”

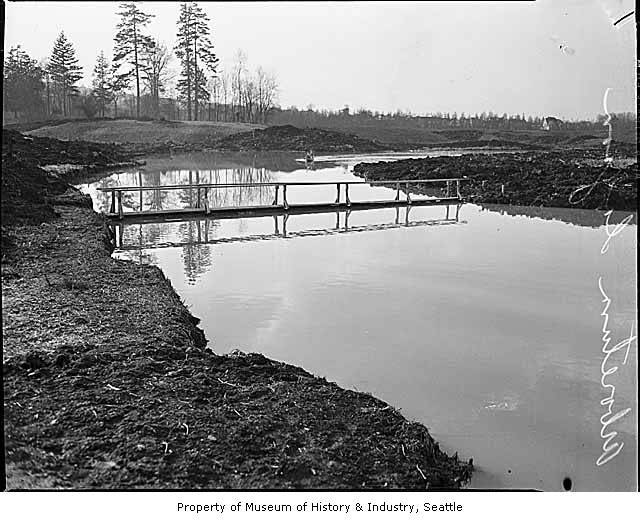

By March 2, 1924, their efforts and those of the surrounding community helped influence the passing of Resolution Number 40 by the Board of Park Commissioners. This action designated all of Washington Park for arboretum purposes.

In 1928, Dean Winkenwerder traveled to Europe at his own expense to visit arboreta and botanical gardens, including Kew Gardens in England. En route, he visited the Arnold Arboretum. His research abroad provided greater informational background which, upon his return, he leveraged to gain more support for the Arboretum.

Despite the enthusiasm of Suzzallo and Winkenwerder, and the passing of Resolution Number 40, Washington Park remained undeveloped and covered with brush through 1930. This was primarily due to a lack of funds for development.