The original 1936 Olmsted Brothers plan for the Arboretum recommended planting trees in an ordered “taxonomic” system. This kind of ordered arrangement sought to classify a collection of specimens by placing them in sequential order. This was intended to allow scientists and students to understand how plants evolved to their present state.

An arboretum functions as a living plant museum. Taxonomic arrangements in museums allow collections to be organized in a logical manner that grants easy access to specimens by researchers. They also are useful in understanding the development of species because the systems physically place specimens in a progressive order that demonstrates their evolutionary development.

The Olmsted Brothers’ J.F. Dawson laid out the taxonomic arrangement in the Arboretum. Dawson used Boston’s Arnold Arboretum as a prototype for arranging the collections of trees. This was done in what the Olmsted Brothers referred to as a “system of botanical sequences.” In this system, a group of plants that would thrive in Seattle was compiled. Then the plants were grouped into their taxonomic families and the amount of space each family would require was determined. The plants were then laid out in an order that began with those deemed to be most primitive, and ending with the more advanced. The Olmsted Brothers firm used a taxonomic system in the Washington Park Arboretum that was developed by German Botanist Adolf Engler and edited by Karl Prantl between 1887 and 1915.

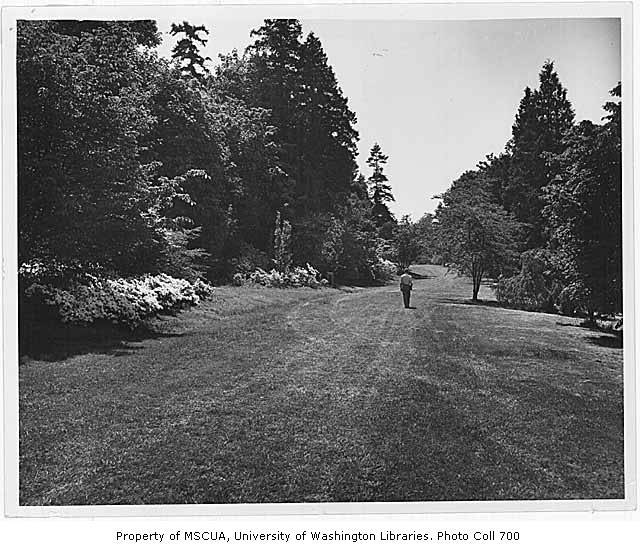

The Engler and Prantl taxonomic system used by the Olmsteds presented problems for the Arboretum that persisted for many years. The “botanical sequences” employed by the Olmsteds did not take into consideration the individual needs of the trees. For example, olive and linden trees, which need little water, were planted in soggy ground, birch and beech trees were planted too close together and were overcrowded. Many trees in their original Olmsted groupings struggled until 1947, when director Brian O. Mulligan intervened. He moved nineteen entire families and several coniferous genera in order to give them proper growing conditions and sufficient space. Today, only three elements of the 1936 Olmsted plan remain in varying degrees–the system of lagoons and ponds, Arboretum Drive, and Azalea Way.

Though generalized locations were, for the most part, followed, the majority of the plantings in the Arboretum departed from the original Olmsted plan of a sequential taxonomic arrangement of tree species. The exception was Otto Holmdahl’s 1938 planting of maples (Acer), soapberry trees (Sapindus), and horse chestnuts (Aesculus). These were relocated to other parts of the Arboretum in 1960, when construction began on the Japanese Garden.