I was very impressed with the story-telling skills of Thor Hanson that I discovered when reading his “The Triumph of Seeds” (see review in the Fall 2015 issue of the “Bulletin”). He makes scientific research easy to understand and an adventure that’s fun!

I was very impressed with the story-telling skills of Thor Hanson that I discovered when reading his “The Triumph of Seeds” (see review in the Fall 2015 issue of the “Bulletin”). He makes scientific research easy to understand and an adventure that’s fun!

“Buzz: The Nature and Necessity of Bees” is Hanson’s newest (2018) book. As before, he combines just the right touch of personal, local experience – he lives on an unidentified island in the Pacific Northwest – with wide-ranging research. For this book, he traveled to Sri Lanka to investigate a bee-like wasp, and to southern Africa, one of the ecosystems where honey bees are native.

“Bees are the vegetarian descendants of a sphecid wasp ancestor from the mid-Cretaceous. That much is known.” As these wasps are not vegetarian, why and how did bees make this dramatic lifestyle change? This is still a mostly unanswered question, but Hanson seeks out some of most recent research and insightful researchers to explore the possibilities.

This led him to participate in “The Bee Course”, a nine-day, intensive study set in the Arizona desert in August. Why there and then? Arizona has the highest concentration of bee species (1,300) in North America and unlike tourists, they don’t mind the heat and are particularly busy during the flush of flowers by many cacti and other wildflowers at that time of year.

During the course, Hanson became smitten with an alkali bee (Nomia sp.), a genus that has an opalescent exoskeleton, “flashing a rainbow of colors that shifted and swirled in the light.” While this species was a rare treasure from his visit to Arizona, he discovered later that near Touchet, Washington, alfalfa farmers have learned to create an environment to nurture native species of alkali bees in exchange for pollinating their crops. This is not a small-scale operation. There are an estimated 18-25 million nesting female alkali bees scattered over 300 acres.

There are other local connections, too. The author profiles Brian Griffin of Bellingham, well-known amongst gardeners and fruit-growers for his commercializing and promotion of keeping orchard mason bees. Hanson also made his own discovery, finding a cliff on a neighboring island to his own that is home to 400,000 digger bees – the largest know population of such bees – amongst a complex community of several other types of bees, wasps, flies, and beetles.

Excerpted from the Spring 2019 Arboretum Bulletin.

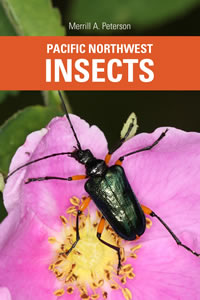

Fascinated by all the small life forms you find in your garden? Perhaps not, but it is still valuable for gardeners to know about them. “Pacific Northwest Insects” by Merrill Peterson will help. This excellent new field guide provides incredible color photos of over 1,200 species native to our region. The scope is the phylum Arthropoda, so this includes all the true insects (bees, beetles, butterflies, flies, etc.) plus centipedes, sow bugs, spider mites, and even spiders and ticks (yikes!).

Fascinated by all the small life forms you find in your garden? Perhaps not, but it is still valuable for gardeners to know about them. “Pacific Northwest Insects” by Merrill Peterson will help. This excellent new field guide provides incredible color photos of over 1,200 species native to our region. The scope is the phylum Arthropoda, so this includes all the true insects (bees, beetles, butterflies, flies, etc.) plus centipedes, sow bugs, spider mites, and even spiders and ticks (yikes!).![[The Brother Gardeners] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/brothergardeners.jpg)

“Designing with Palms” by Jason Dewees is by a San Francisco based author, who profiles garden motifs evoked by palms across the country. For instance, Chamaerops humilis suggests a Mediterranean garrigue, an ecosystem with low shrubs, including rosemary and lavender, like one might find in a Seattle landscape.

“Designing with Palms” by Jason Dewees is by a San Francisco based author, who profiles garden motifs evoked by palms across the country. For instance, Chamaerops humilis suggests a Mediterranean garrigue, an ecosystem with low shrubs, including rosemary and lavender, like one might find in a Seattle landscape.![[Flora of Middle Earth] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/floraofmiddle-earth.jpg)

![[Flora of the Pacific Northwest] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/floraofthePacificNorthwestfull.jpg)

![[book title] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/AbernethyForest.jpg)

![[book title] cover](https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/graphix/Mannahatta.jpg)

It was on a visit to the United States that Alice Lounsberry (1873-1949) of Boston, some 25 years younger, introduced herself to Australian painter Ellis Rowan. Lounsberry convinced Rowan to travel with her for two years, providing illustrations for three books she wrote on native plants: “

It was on a visit to the United States that Alice Lounsberry (1873-1949) of Boston, some 25 years younger, introduced herself to Australian painter Ellis Rowan. Lounsberry convinced Rowan to travel with her for two years, providing illustrations for three books she wrote on native plants: “