Mapping the Black Panther Party in Key Cities

by Arianne Hermida

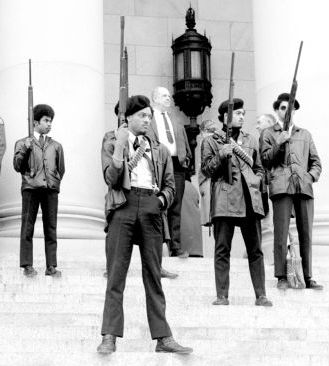

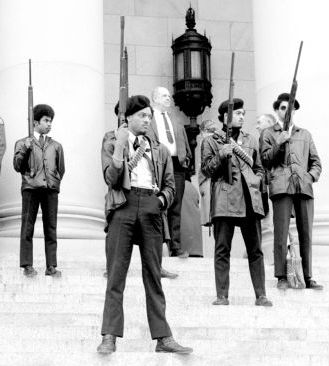

Members of the Seattle chapter stage protest at the Washington State capitol in Olympia, February 28, 1969 (photo: Washington State Archives)The Black Panther Party for Self Defense was founded in October 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale who had met at Merritt College in Oakland, California. Dedicated to revolutionary internationalism and armed self-defense of Black communities, the Panthers initially operated in Oakland and Berkeley then in San Francisco and Richmond. In May 1967, the organization gained world-wide media attention when Seale led a contingent of heavily-armed Panthers into the California state capitol building in Sacramento to demonstrate their opposition to a proposed law that would restrict the right to carry loaded weapons on city streets. With membership surging in the Bay Area, self proclaimed Panther units were established in many other locations. Faced with this unauthorized expansion, in spring 1968 the Oakland organization began officially chartering chapters, requiring allegiance to BPP principles and centralizing authority. While BPP adherents could be found in cities and towns across the country, officially the Party chartered thirteen chapters.

Members of the Seattle chapter stage protest at the Washington State capitol in Olympia, February 28, 1969 (photo: Washington State Archives)The Black Panther Party for Self Defense was founded in October 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale who had met at Merritt College in Oakland, California. Dedicated to revolutionary internationalism and armed self-defense of Black communities, the Panthers initially operated in Oakland and Berkeley then in San Francisco and Richmond. In May 1967, the organization gained world-wide media attention when Seale led a contingent of heavily-armed Panthers into the California state capitol building in Sacramento to demonstrate their opposition to a proposed law that would restrict the right to carry loaded weapons on city streets. With membership surging in the Bay Area, self proclaimed Panther units were established in many other locations. Faced with this unauthorized expansion, in spring 1968 the Oakland organization began officially chartering chapters, requiring allegiance to BPP principles and centralizing authority. While BPP adherents could be found in cities and towns across the country, officially the Party chartered thirteen chapters.

In the maps that follow we track the geography of the BPP in the six metropolitan areas where the Panthers enrolled the most members and made the greatest impact: Oakland-SF Bay Area; New York; Chicago; Los Angeles; Seattle; Philadelphia. The maps show BPP offices, facilities, and the location of key events, combining historic images when we have them with google street views of the locations today. Arianne Hermida researched and coordinates this section.

Oakland - San Francisco - Berkeley- Richmond

New York

The Harlem chapter may have been the first unit of the Black Panther Party organized outside of the Bay Area. Expanding quickly, the chapter issued a regular bulletin called the People's Community News. With the Harlem unit serving as headquarters, branch offices were established in Brooklyn, the Bronx, Mt. Vernon, Corona-East Elmhurst, Staten Island and Jamaica. The BPP created an array of social programs including a free community health center, two free breakfast programs, and the Black Panther Athletic Club, a youth group. The New York BPP chapter was particularly active in organizing public demonstrations beginning with Free Huey rallies and then turning to the defense of 21 New York Panthers who were indicted in 1969 on charges related to an alleged bomb plot of department stores, a streetcar, and a police station. Disagreements with the national office over support for imprisoned members and other issues came to a head in 1971 when the New York Panther organization broke with Oakland and established a new East Coast Black Panther Party with its own newspaper, Right On. Although under constant pressure from the police and FBI, the new organization carried on, finally closing its office in 1981.

.

Chicago

In 1968, two independent groups in Chicago began unofficial chapters of the Black Panther Party, one on the West Side and the other on the South Side. The two merged after national headquarters granted the South Side branch an official charter, then expanded from 40 members to over 300 within a few months. The Illinois Black Panther Party and its leadership, experienced in organizing and civil rights, based their strategy on cooperation with other local groups. They attempted alliances with several rival street gangs with the goal of turning them into revolutionary organizations or at least securing the ability to sell the Black Panther Community News in gang-controlled territory. They also formed an interracial revolutionary group, the Rainbow Coalition, allying with the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican organization, and other radicals. The Chicago BPP ran free breakfast programs for children that served up to 4,000 daily and also ran a free medical clinic. But this chapter is most often remembered not for their service but for their tragedies. Panthers and police were killed in gun battles in July and November 1969. Then on December 4, members of the Chicago Police Department, in coordination with the FBI, raided the apartment of BPP Deputy Chairman Fred Hampton. Hampton was executed in the bed where he slept; Mark Clark also died; several others were wounded. Though severely damaged and under constant police surveillance, the chapter remained active, maintaining their community programs until 1974.

Los Angeles

In November of 1967, an undercover FBI agent infiltrating the national Black Panther Party headquarters created the Los Angeles Black Panther Party chapter. The Party exposed and expelled the undercover agent shortly thereafter and the chapter blossomed under new leadership, gaining hundreds of new recruits in early 1968 then launching a free breakfast program and free medical clinic. As the BPP grew, the chapter came into conflict with Ron Karenga’s US Organization, dedicated to militant Black Nationalism. A shoot-out between the groups on the UCLA campus left two of the LA Panther leaders dead. Shootouts with Los Angeles police took the lives of other members, and the LAPD and FBI conducted repeated raids and nearly constant harassment, including arresting 42 Panthers in one two-week period. Continued assault by the LAPD and FBI stripped away the foundation of the chapter until it crumbled in 1970.

>

Seattle

Chartered in early 1968, the Seattle chapter of the Black Panther Party quickly captured media attention and police attention. Intervening to protect Black students in schools as well as patroling to address police brutality, the organization achieved significant support not only in the Black community, which was small compared to most cities where Panthers established strong organizations, but also among Asian American and white radicals. Attention multiplied in February 1969 when, duplicating the Sacramento incident, Seattle Panthers appeared with rifles at the state capital in Olympia to protest a bill that would limit the carrying of firearms. Arrests, trials, and the death of several Panthers at the hands of police followed but in 1970 the chapter managed to establish a breakfast program, a medical clinic, and youth education programs. Early that year, and just months after the Chicago raid in which Fred Hampton was murdered, Justice Department officials urged the Seattle Police Department to join in an attack on the Seattle Panther headquarters. Newly elected Mayor Wes Uhlman, a 34-year-old antiwar liberal, said no and threatened to expose the Nixon administration plans. It was a decision that saved lives even while there was no let up in other forms of FBI and police harrasment. The chapter lasted longer than most and the breakfast program and medical clinics continued after the chapter disbanded in 1977.

Philadelphia

Philadelphia’s Black Panther Party chapter began in 1968 and lasted until roughly 1973, though it had lost much of its membership by 1971. The chapter’s founding committee numbered 10-15 and the group increased eightfold within a few months, prompting the opening of a second Party office. The chapter sponsored free clothing, grocery, and breakfast programs, a community protection patrol to combat violence and police brutality, a free health clinic, political education classes required for members and open to the public, and a free library that primarily housed works by black authors (a community resource unique to this chapter). As in other cities with a Black Panther presence, Philadelphia police frequently arrested members without cause and raided offices, sometimes destroying them and forcing the Panthers to move elsewhere. Police oppression and internal strife led to a decline in membership following 1970, though the chapter’s community programs continued for another two years.

>

Members of the Seattle chapter stage protest at the Washington State capitol in Olympia, February 28, 1969 (photo: Washington State Archives)

Members of the Seattle chapter stage protest at the Washington State capitol in Olympia, February 28, 1969 (photo: Washington State Archives)