by Jonathan Garlock

The Knights of Labor was the largest and most extensive association of workers in 19th century America. Organized in 1869, the movement grew slowly in the 1870s, then surged in the 1880s, reaching a peak membership approaching one million in 1886-1887 with Local Assemblies spread across the country in more than 5,600 cities and towns. Its spectacular growth owed much to a bold agenda and flexible organizational plan. The Knights operated as both a trade union federation and a political movement. Envisioning a "Cooperative Commonwealth" in which producer cooperatives and nationalized railroads would replace monopolistic capitalism, the Knights launched dozens of local and state labor parties and hundreds of worker-owned cooperatives. Meanwhile, thousands of Local Assemblies represented members in their work places, bargaining with employers, threatening and conducting strikes. Inclusivity was the other hallmark of the KOL (especially in comparison to the American Federation of Labor unions that followed). The Knights included African American workers and counted 246 local assemblies organized by women workers. [Introduction continues below map]

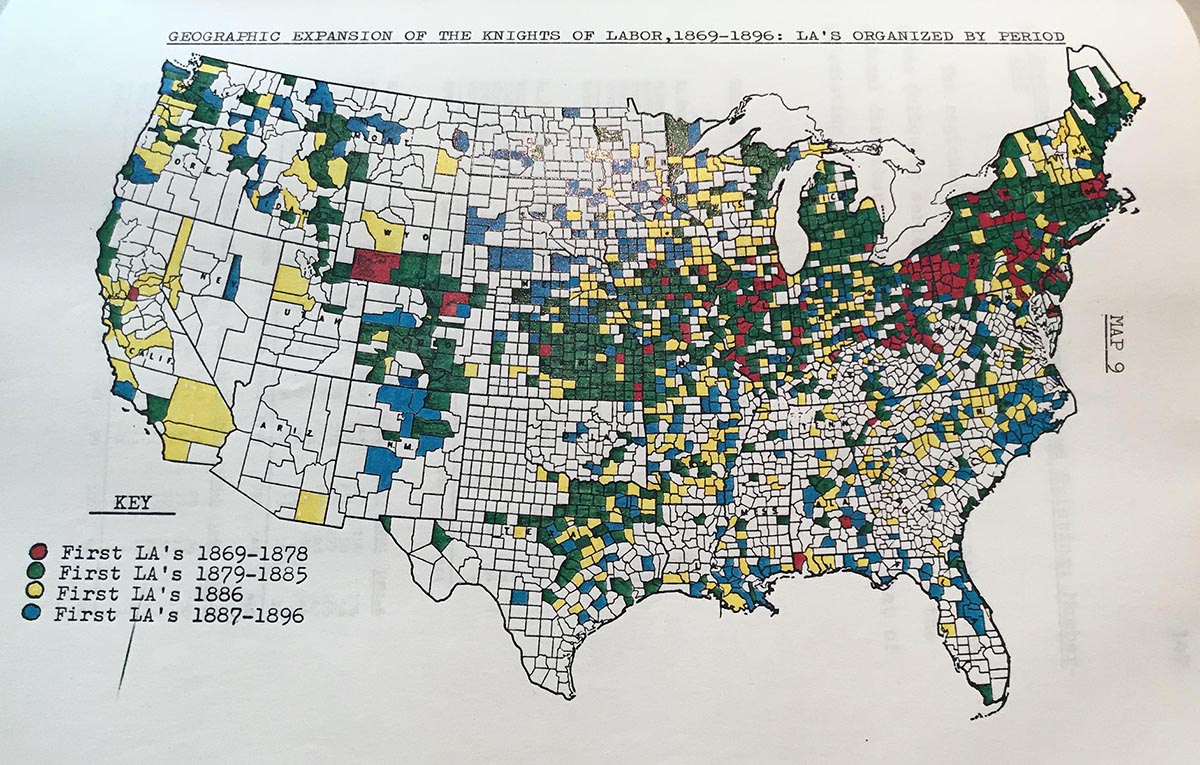

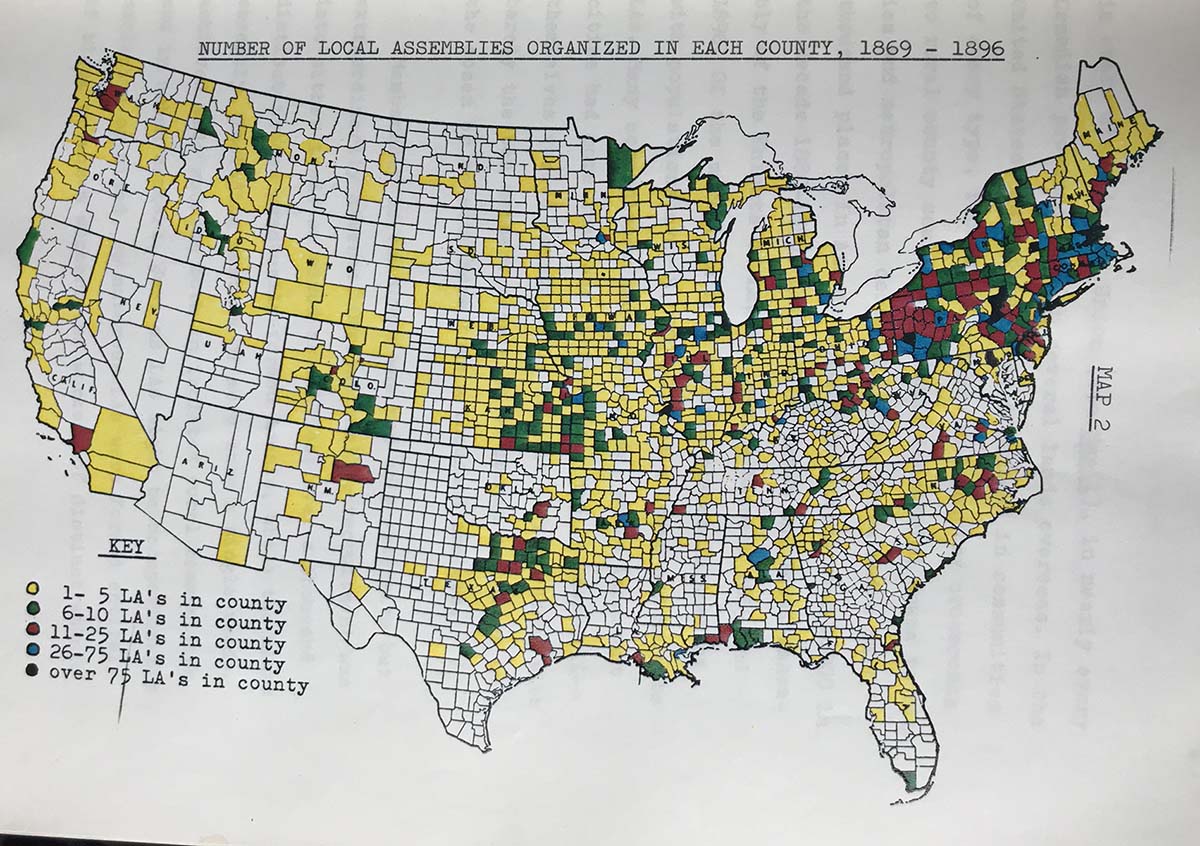

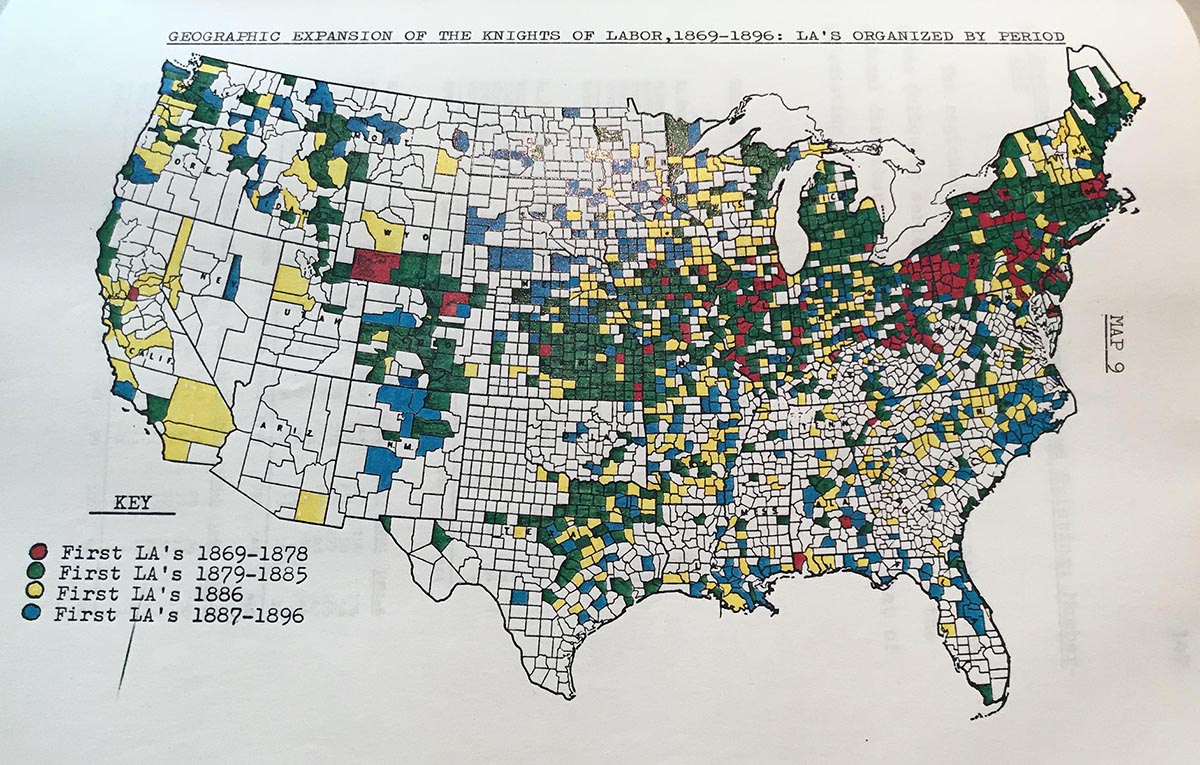

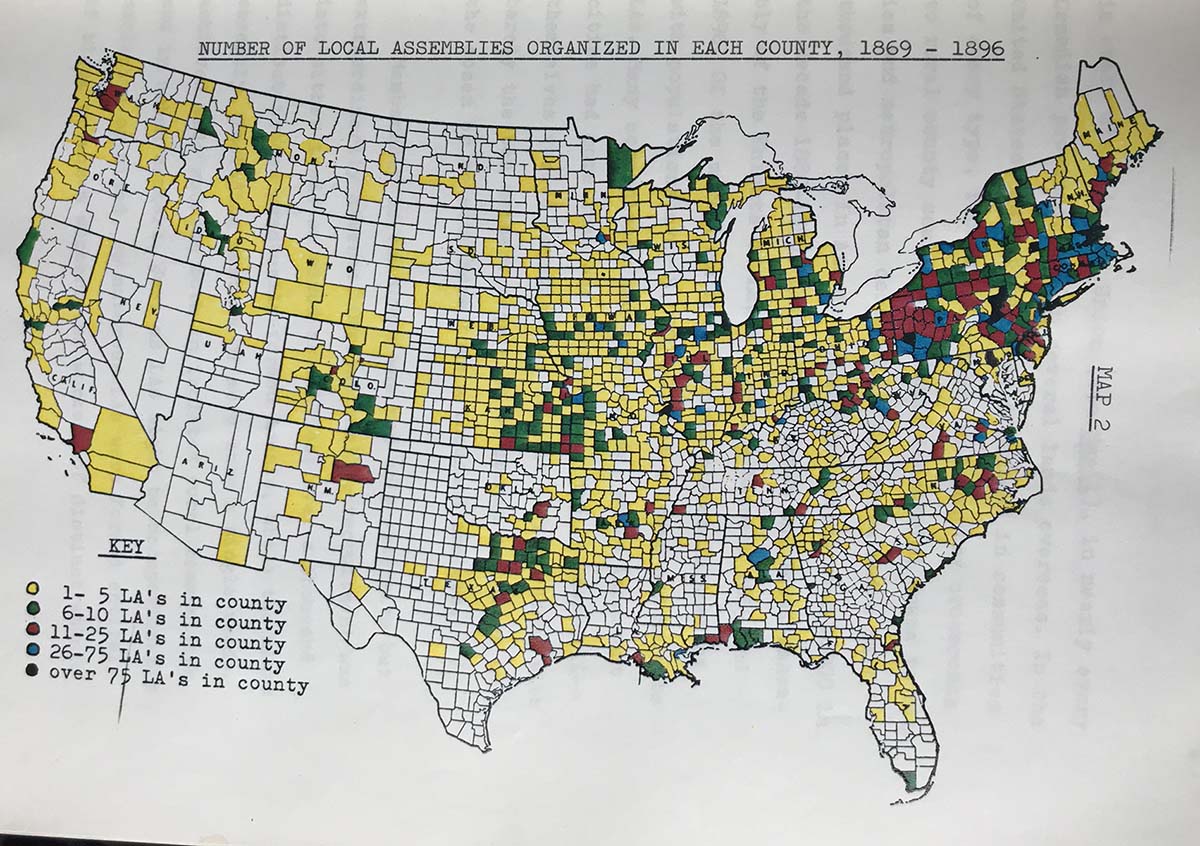

These maps and charts locate nearly 12,000 Local Assemblies of the Knights of Labor. They are based on data gathered by Jonathan Garlock and published in Guide to the Local Assemblies of the Knights of Labor (Greenwood Press, 1982). The maps are hosted by Tableau Public and may take a few seconds to respond. If slow, refresh the page.

Move between seven maps and charts by selecting tabs below

Sources: These maps and charts are based on The Knights of Labor Data Bank, completed in 1973 by Jonathan Garlock and published in Guide to the Local Assemblies of the Knights of Labor (Greenwood Press, 1982) and "Structural Analysis of the Knights of Labor" (PhD Dissertation, University of Rochester, 1974). We have used the machine-readable version of the Data Bank on deposit at Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Knights of Labor Assemblies, 1879-1889 [Computer File]. ICPSR0029. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. Assisted by N.C. Builder, Garlock built the Knights of Labor Data Bank from close research in a variety of sources especially Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Knights of Labor [1879-1896] and the Knights official Journal of United Labor [1880-1896]. In the years since these data became available, historians have drawn on them to revise understandings of this pivotal labor movement. The interactive maps, charts, and datalists above now make this invaluable data more accessible and potentially open the door to more research and new interpretations.

Definitions and data clarifications:

The Knights of Labor

classified Local Assemblies as either Trade or Mixed

LA's. It has been generally but erroneously assumed that,

on the one hand, trade assemblies were strictly craft assemblies

admitting members of a single craft only, and

on the other hand that mixed assemblies necessarily included

members of many trades. Actually, classification

by the Order proceeded in accordance with the 'rule of

10' and derivative definitions. According to the rule of

ten, (a) it required at least ten members to form an LA;

(b) it required that ten members at least be of the same

trade tor the assembly to be assigned to that trade. If there were more than ten

members in each of two or more trades, the LA was designated

Mixed. Mixed LA's are not as heterogeneous, nor

trade LA's as homogeneous in their occupational composition

as is often assumed.

Demographic data comes principally from Journal of United Labor monthly summaries, which designate many LA's "women," "colored," "German," etc. No information was recorded for most assemblies. That does not necessarily mean that they were all white or all male. Moreover, while some immigrant nationalities were flagged, the two largest immigrant backgrounds, Irish and English, were not. In other words, do not read too much into the category "white or no info."

Introduction

The Knights of Labor was the largest and most extensive association of workers in 19th century America. Organized in 1869, the movement grew slowly in the 1870s, then surged in the 1880s, reaching a peak membership approaching one million in 1886-1887 with Local Assemblies spread across the country in more than 5,600 cities and towns. Its spectacular growth owed much to a bold agenda and flexible organizational plan. The Knights operated as both a trade union federation and a political movement. Envisioning a "Cooperative Commonwealth" in which producer cooperatives and nationalized railroads would replace monopolistic capitalism, the Knights launched dozens of local and state labor parties and hundreds of worker-owned cooperatives. Meanwhile, thousands of Local Assemblies represented members in their work places, bargaining with employers, threatening and conducting strikes. Inclusivity was the other hallmark of the KOL (especially in comparison to the American Federation of Labor unions that followed). The Knights included African American workers and counted 246 local assemblies organized by women workers.

The history of the Knights divides more or less by decades. Founded in 1869 by a group of Philadelphia garment workers whose trade union had foundered, The Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor was conceived as a secret society whose members were bound by oaths and rituals designed to offer protection against employer tactics that often broke unions. It expanded quietly in the 1870s under the leadership of founder and Grand Master Workman Uriah Stevens, with most of the expansion in Pennsylvania and neighboring Ohio and, especially in the era of the Molly Maguires, in the coal mining districts. Coal miners, above all other trades, were attracted to the organization and the Knights' success in that industry paved the way for the United Mine Workers of America which took over as the Knights lost momentum at the end of the century.

Stephens resigned in 1879 and was succeeded by Terence V. Powderly who would transform the organization and lead it during its great period or growth and influence. Dropping the secrecy rituals, the organization also shortened its name, responding to Irish Catholics (including Powderly) who objected to the "Noble and Holy Order" prefix. Membership surged from the start of the decade and then exploded in 1885 and 1886 as the Knights took the lead in the 8-hour-day movement and gained credit for winning strikes. For 1886, the organization reported 729,677 members in 5,892 Local Assemblies, but this was actually an undercount. The organization had trouble keeping track of local assemblies and membership in the midst of this growth period. As explained in "Structural Analysis of the Knights of Labor," the actual number was close to one million.[1]

The next decade was difficult. The Knights lost an ill-conceived railroad strike in 1886 which was followed by a blacklist in that critical industry. The Haymarket bombing and trial of anarchists in Chicago led to a wave of anti-radical/anti-labor hysteria that further hurt the organization. That same year, cigar-maker Samuel Gompers and many of the best organized craft unions left the Knights and launched a rival body, the American Federation of Labor. Competition between the two labor federations favored the AFL, whose model of craft exclusivity and closed-shop bargaining helped it survive the depression of 1893. The economy recovered in 1896, but not the Knights of Labor. By the turn of the century, the movement was fading fast.

Geography of the Knights of Labor

Between 1869 and 1896 the Order spanned the continent with fifteen thousand Local Assemblies. Assemblies were formed in every state in the US, in nearly every Canadian province, and in several lands overseas. In the United States, assemblies were organized in communities of every type, from mining camps and country crossroads to rural county seats; from small industrial towns to cities and metropolitan centers. Of the three and a half thousand places in America with populations over 1,000 in the decade 1880-1890, half had at least one Local Assembly of the Knights of Labor sometime between 1869 and 1896. Of the more than four hundred places in America with populations over 8,000, all but a dozen had Knights LAs. Many communities had several LAs, while important cities had more than one hundred.

Assemblies themselves varied considerably in size — from those with barely the ten members requisite to obtain a charter to the dozen or so with more than a thousand members. Membership in the Order was not only extensive but extraordinarily diverse. Occupationally, recruitment was into either trade or mixed assemblies: over a thousand distinct trades eventually formed locals, while the mixed assembly, including members of more than a single trade, achieved wide success both in isolated rural communities and in urban centers. Just as LAs might be occupationally exclusive or mixed, so numerous LAs were formed entirely of black or women workers, or workers of distinct ethnic origins, while in many assemblies membership cut across racial, gender, and ethnic lines.

Mapping Then and Now

It is instructive to think about how the the tools of historians have changed since the 1970s when this project was begun. It was heralded at the time as a pioneering example of "quantitative history." whereas this version is labeled "digital history." There was nothing digital about the original work. Research involved reading printed or microfilmed sources one item at a time, taking notes, consolidating and cross checking information, then key punching computer cards, one card for each local assembly. Hundreds of hours were spent with atlases, finding locations and identifying the associated counties. The population of each location was coded from census data for 1880 and 1890. A mainframe computer did the work of producing counts of various kinds and tables that became part of Garlock's dissertation. The charts had to be drawn by hand. The dissertation also featured twenty-four colored maps, two of which appear below. The xerographic technology used to produce color copies was cutting edge in 1973.

The first map shows the expansion of the Knights by color coded time period

The second map shows the number of local assemblies in each county.

Notes

[1] Jonathan Garlock, "Structural Analysis of the Knights of Labor" (PhD Dissertation, University of Rochester, 1974), 222-231.