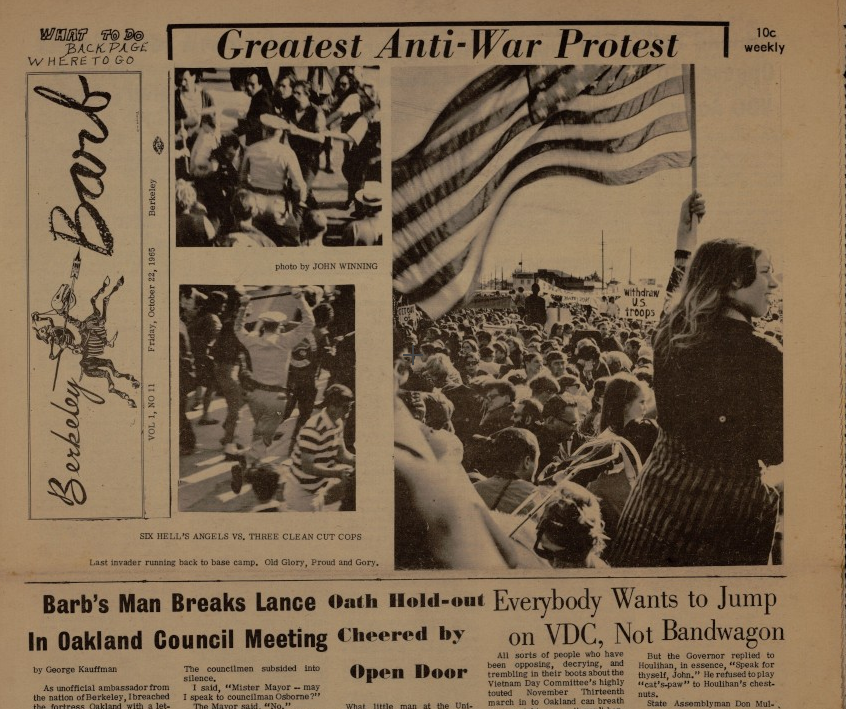

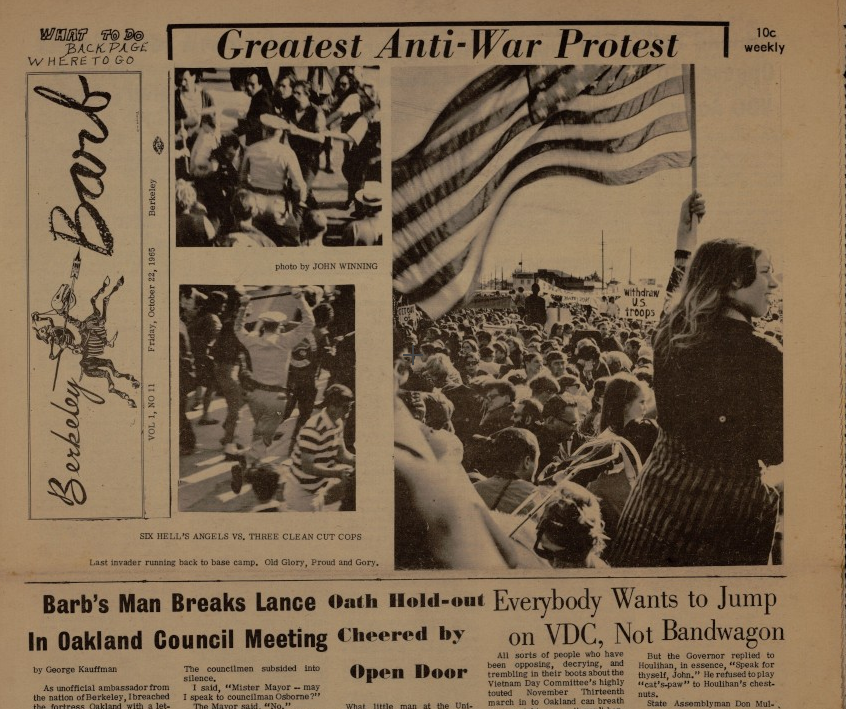

In one of its early issues, the Berkeley Barb celebrated the "Greatest Anti War Protest." (October 22, 1965)

In one of its early issues, the Berkeley Barb celebrated the "Greatest Anti War Protest." (October 22, 1965)

by Katie Anastas

The social movements of the 1960s and 1970s transformed American politics, social life, and culture. From civil rights groups, to feminist organizations, to environmental activists, to antiwar GI’s, Americans mobilized in new ways to promote social change. Some of the notable groups that we’ve mapped include the Black Panther Party, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the United Farm Workers.

Today, Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms allow us to publish and read diverse opinions, organize protests and demonstrations, support the organizations and causes we care about, and, in some cases, speak directly with people in power.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the underground press served that same purpose, giving voice to marginalized groups and helping them build stronger communities.

Before the Vietnam War era, the term “underground newspaper” was used to describe the publications of resistance groups in totalitarian societies, such as the Moscow-based underground poetry journal Sintaksis (Petrov). Starting in the mid 1960s, young journalists repurposed the underground label to describe their radical and countercultural publications.

News media at the time was dominated by three television networks and two wire services that fed a uniform package of national and international news to urban daily newspapers. The underground press broke into this monopoly, publishing on subjects and with viewpoints that could not be found in mainstream media, and introducing graphics and design that defied every convention of print publishing. Radical in content, radical in design, and often highly unconventional in all aspects of their operations, the underground press represented something of a precursor to disruptive social media revolution of the last two decades.

Nothing Standard

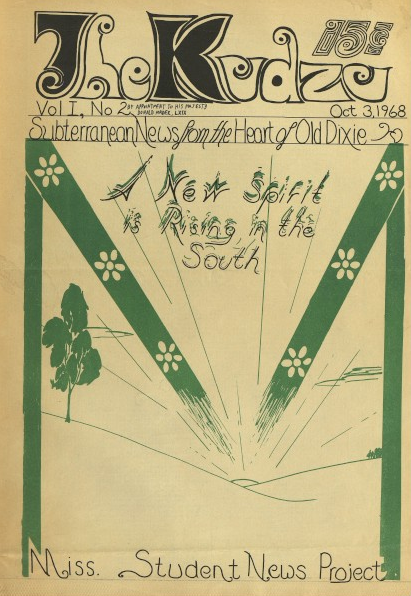

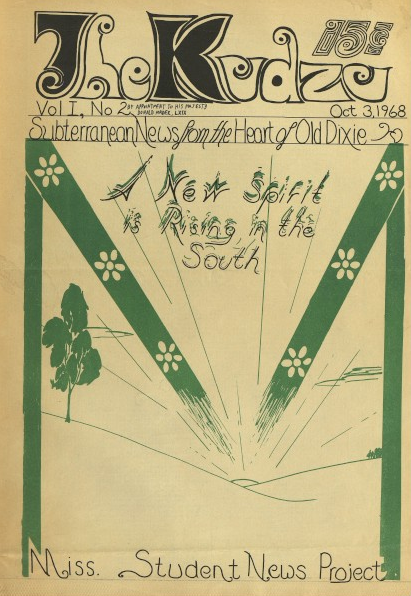

The Kudsu, published in Mississippi in 1968, took its name from the upiquitous vine that spreads through the forests of the South, and proclaimed "A New Spirit is Rising in the South."

The Kudsu, published in Mississippi in 1968, took its name from the upiquitous vine that spreads through the forests of the South, and proclaimed "A New Spirit is Rising in the South."

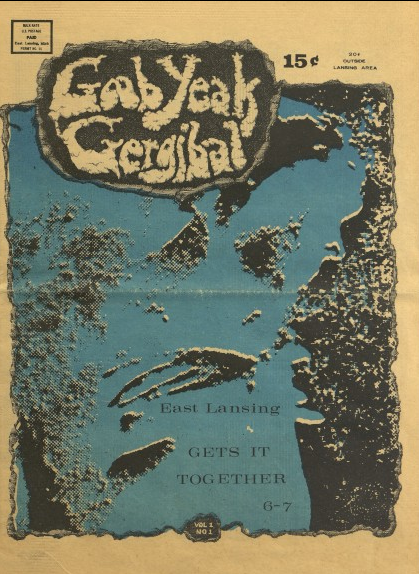

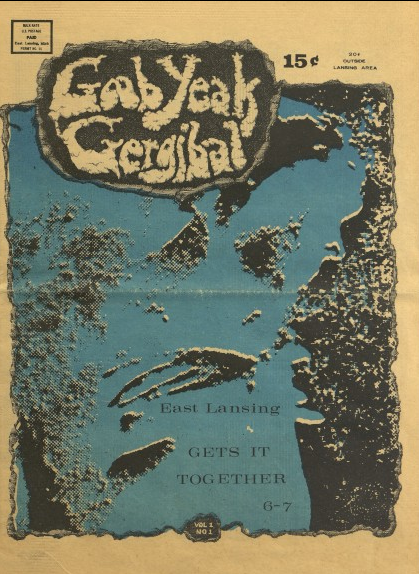

The creativity of the underground press was evident in the names that founders chose for their little newspapers. Some were mildly respectable even while signally independence, like the several versions of “Free Press,” but others made their political stances and subject matter clear to potential readers. LGBT papers included Radicalqueen in Philadelphia, Effeminist in Berkeley, and Gayzette in San Francisco. Literary magazines had titles like Amper&and and blewointmentpress. Some GI papers included the name of their city or base in their titles, such as My Knot published in Minot, North Dakota, Can You Bear McNair published at McNair Kaserne, and Offul Times published at the Offut Air Force Base. Other GI papers were Proper Gander in Germany, Affluent Drool in Chicago, and Fun, Travel and Adventure – a cleaner take on the acronym FTA – in Louisville. Underground papers had titles like Free Spaghetti Dinner in Santa Cruz, California, Goob Yeak Gergibal in East Lansing, Pterodactyl in Grinnel, Iowa, and Raisin Bread in Minneapolis.

Critical journalism was one of the common commitments of the underground newspapers. Attacking the mainstream media for uncritical coverage of the American war in the Vietnam, for its casual racism and sexism, for conservative positions on drugs, sex, and the emerging counterculture, the underground press allowed radical groups to directly respond to established media and challenge the narratives presented to the public.

In addition to challenging the established media’s reporting and writing styles, the underground press also experimented with layout and design. This resulted in a wide variety of production methods. Some had elaborate photo collages and were printed in color, while others were made up of mostly handwritten text. Some were consistently published each week or month, and others were published a few times a year when the writers had enough funding. Many groups and individuals also published literary magazines and books of poetry. Each publication was slightly different, making the underground press truly representative of the wide range in opinions and tactics of different groups during the 1960s and 1970s.

Students and ex-students from Michigan State University in Lansing had published an underground named The Paper beginning in 1965. In 1969, it was mysteriously renamed Goob Yeak Geribal

Students and ex-students from Michigan State University in Lansing had published an underground named The Paper beginning in 1965. In 1969, it was mysteriously renamed Goob Yeak Geribal

The groups that produced underground and alternative papers were incredibly diverse. In just one city, groups with very different focuses could publish newspapers and spread their ideas. In Baltimore, for example, there were at least two underground newspapers, three antiwar papers published by GI’s, one antiwar paper published by local civilians, a literary magazine, and a feminist paper.

Many newspapers focused on very specific topics. The Radical Therapist, published in Minot, North Dakota, was a forum for psychologists and social workers to discuss mainstream psychiatry’s problematic attitudes toward women, homosexuals, and people of color. Alternative, published in Naperville, Illinois, was written by high school students and went underground after the school board refused to recognize it. The Green Revolution, published in Freeland, Maryland, shared farming advice for people interested in starting communes. But We Didn’t Know was published by the "Four of Us" Defense Committee, a group that sought the freedom of four protesters who poured blood over draft records at their local Selective Service Office.

Alternative business methods

Many underground papers were owned collectively, and staff members were involved with all decisions regarding how the paper was run. In his book, Smoking Typewriters, John McMillian notes that while this model allowed for free expression if ideas, many writers learned collective ownership “could also be burdensome, inefficient, and alienating” when editors had little power. (McMillian)

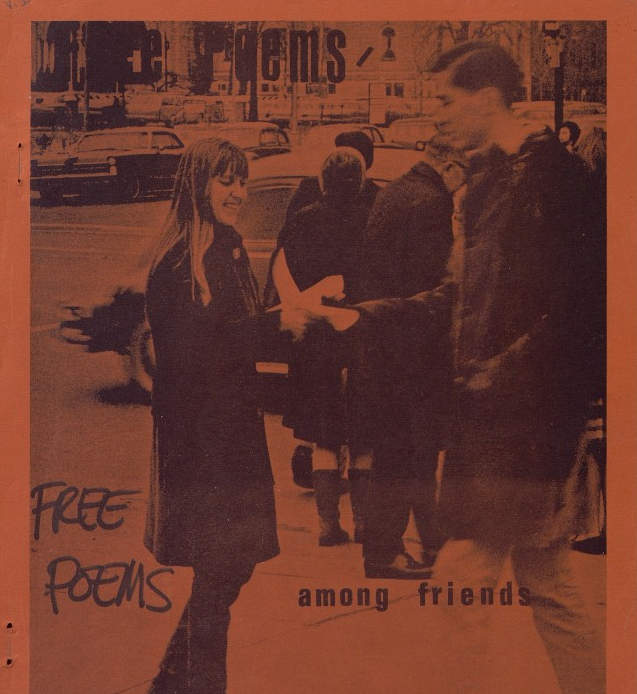

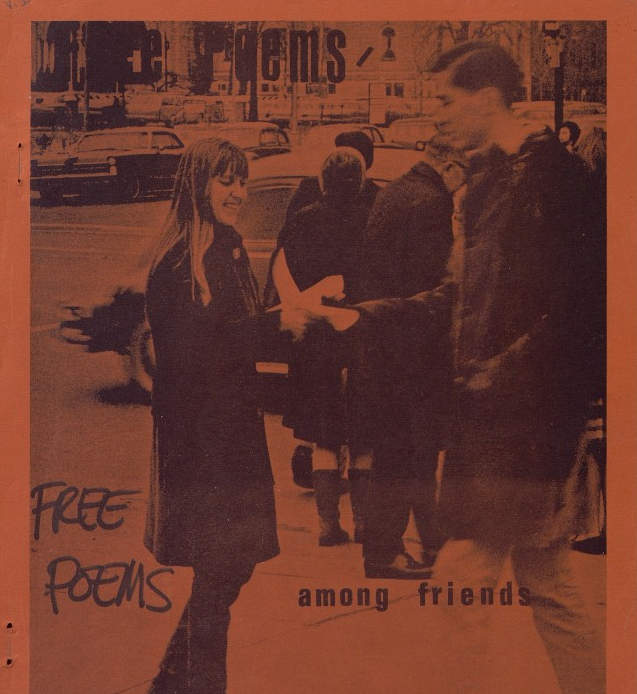

Published in Detroit from 1965 to 1967, Free Poems Among Friends was one of a large number of literary undergrounds.

Published in Detroit from 1965 to 1967, Free Poems Among Friends was one of a large number of literary undergrounds.

Most undergrounds initially relied on street sales, typically charging ten cents a copy with the proceeds split between seller and newspaper. The larger newspapers depended on a crew of loyal street sellers but in other cases writers, artists, and the whole staff pitched in to hawk each new edition. In any case, undergrounds quickly added to the colorful street culture of their communities. Free distribution became more and more common in the 1970s. Those that were distributed for free intitially– usually GI and campus papers – often asked for donations from readers and were published infrequently. Eventually, most papers switched to free distribution in news boxes and increasingly relied on ad revenue. By 1972-73, these newspapers usually pivoted from using the label underground to the term “alternative press.”

Many editors shared stories of persecution by police, military authority, campus administration, and unsympathetic civilians in their papers. In his book Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press, Ken Wachsberger describes the harassment he and others experienced while publishing an underground paper called The Kudzu in Jackson, Mississippi. In addition to arrests, beatings, and bomb threats, some contributors faced rejection from their families.

“Equally as troubling as the arrests were the more personal incidents of harassment,” Wachsberger writes. “A number of college students associated with the paper were financially cut off by their parents. Some high school kids were expelled from school and sent to military academies…We lived a stressful lifestyle that was only overcome by youthful exuberance and comradery.” (Wachsberger)

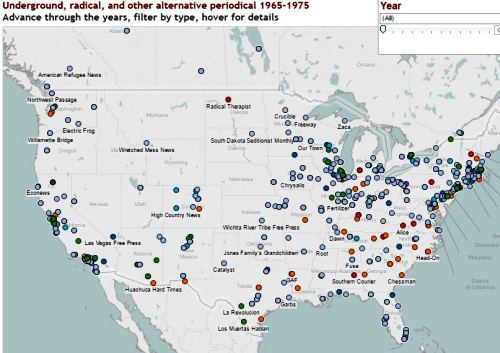

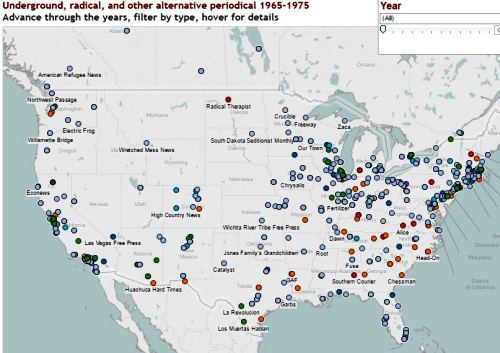

Click to view interactive maps of more than 2,600 underground and alternative periodicals

Click to view interactive maps of more than 2,600 underground and alternative periodicals

The geography of the underground press is demonstrated in the accompanying maps showing more than 2,600 publications. California was home to more newspapers than any other state – 452 by our count – followed by New York and Illinois. But undergrounds were to be found in every state and not only in big cities and university towns. Anti-war GI undergrounds circulated near most military bases, and there was no shortage of creative and effective newspapers based in small towns and unexpected places. The wonderfully named Wretched Mess News held forth for more than two years in West Yellowstone, Montana.

Underground Press Syndicate and the Liberation News Service

Many newspapers sought to collaborate and support each other, regardless of whether they covered similar topics. GI newspapers often included lists of other papers and their mailing addresses at military bases across the country. Campus underground papers encouraged readers to support local antiwar papers, labor publications, and newspapers published by civil rights groups. An African American newspaper might encourage readers to support the grape boycott organized by the United Farm Workers. The underground press illustrates the overlapping concerns of these groups and offers insights at how they used their publications to support each other. Two underground news services helped facilitate this collaboration at a national level: the Underground Press Syndicate and the Liberation News Service.

The Underground Press Syndicate was a network of underground newspapers formed in 1966 by the publishers of the East Village Other, the Los Angeles Free Press, the Berkeley Barb, the Paper, and Fifth Estate. Membership grew from 15 newspapers in November 1966 to 271 papers in 1971. Members could freely reprint each other’s content, which gave small papers access to a large amount of content and helped larger newspapers share their writing throughout the country and world. The Underground Press Syndicate also held several conferences hosted by underground papers around the country, which allowed newspaper editors to meet and collaborate.

The Liberation News Service was founded in 1967 and distributed content to countercultural papers throughout the country. The service, which was founded by former editors of student newspapers, gained attention from the underground press scene when it provided outlets with insider coverage of protests at the Pentagon in October 1967 and strikes at Columbia University in 1968 (LNS records). By 1972, the service had almost 800 subscribers and sent content twice a week (Stone). It was largely volunteer-run and relied on funding from subscriptions and donations.

Big City Undergrounds

Every major city had at least one underground paper that achieved large circulation numbers. These included the Village Voice in New York (with 130,000 readers), the Los Angeles Free Press (100,000 readers), the Rag in Austin (10,000 readers), the Phoenix in Boston, and the Paper in East Lansing, Michigan. The Bay Area was home to multiple major undergrounds, including the Berkeley Barb (with 85,000 readers), the San Francisco Bay Guardian (with 30,000 readers), and the Black Panther (with 85,000 readers).

These papers published news on a variety of topics, including antiwar demonstrations, campus protests, civil rights demonstrations, and other social movements. While smaller papers in these cities may have covered each of those topics individually and with more depth, the larger papers helped spread these ideas to a wider variety of readers.

Black Power Undergrounds

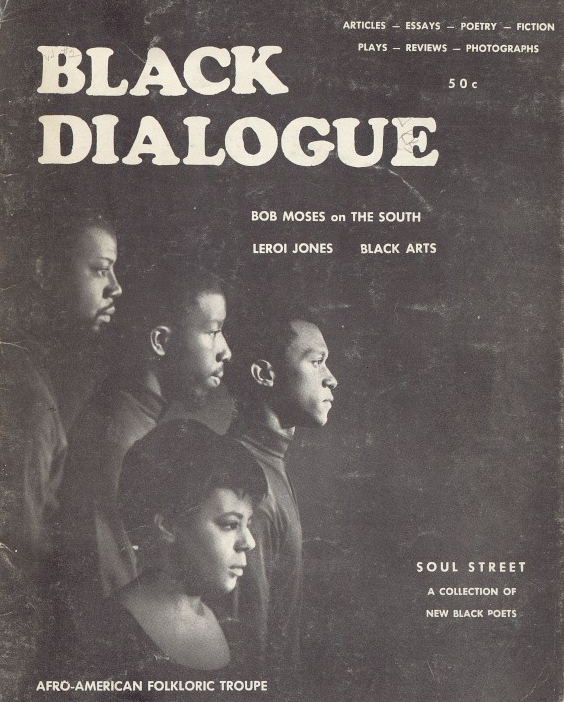

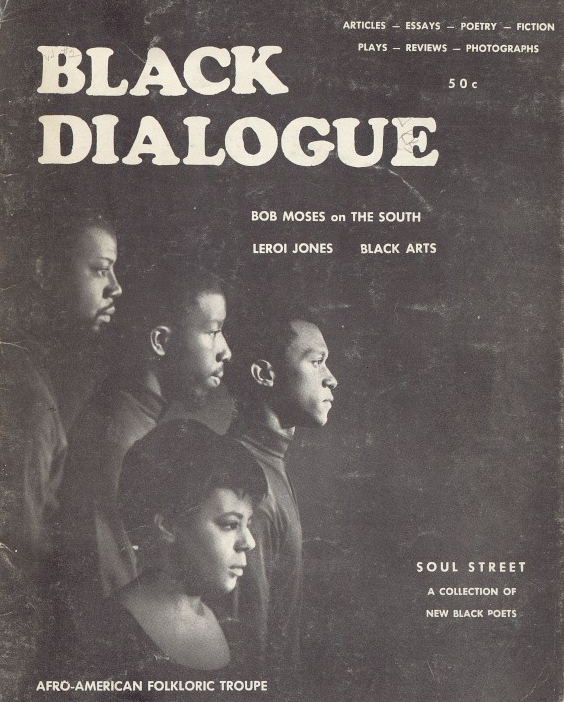

Based in San Franciso, Black Dialogue published articles, essays, fiction, poety, and reviews by African American writers. It's last issues appeared in 1970.

Based in San Franciso, Black Dialogue published articles, essays, fiction, poety, and reviews by African American writers. It's last issues appeared in 1970.

African American activists also published newspapers in many cities, competing with long-established African American newspapers – like the Chicago Defender and Baltimore Afro American – that seemed tame and traditional to the young radicals. Like the rest of the underground press, the papers varied by topic, frequency, and circulation.

Published in San Francisco by the Black Panther Party, the Black Panther contained editorials opposing police, poverty programs and government subsidies, politicians, capitalism, and race riots. It called for employment opportunities, decent housing, truthful education about the U.S., exemption of African Americans from the military, an end to police brutality, and freedom for all African Americans in prison. It reached 85,000 readers.

Muhammad Speaks was published by the Nation of Islam in Chicago. It discussed religion, criminal justice, police brutality, and anti-imperialism. The Colonist was published by members of the Black Student Union at Stanford University and covered racism on campus, black student activism, and local cultural events.

In San Francisco, Black Dialogue published articles, essays, poetry, fiction, and plays by African American writers. In New York, Black Culture Weekly was a weekly arts magazine.

Seattle’s Afro-American Journal included articles from members of the Black Panther Party, the Nation of Islam, and other groups that supported the black power movement. It called for improved public education and a school integration system that gave African American families more control, especially in Seattle’s Central District. Black Liberation News based in Ontario, Canada, Behind the Shield in Madison, Wisconsin, and the Black Liberator in Chicago were examples of outspoken and militant Black Power undergrounds.

Chicano Undergrounds

.png) Published by the United Farm Workers union, El Macriado "the voice of the farmworker" produced its first issue in 1964, its last in 1976.

Published by the United Farm Workers union, El Macriado "the voice of the farmworker" produced its first issue in 1964, its last in 1976.

Several groups involved in the Chicano movement published underground newspapers, mostly in California and Texas. Many Chicano newspapers were published by student groups, such as Chicano studies departments at universities, chapters of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA), and high school students.

Non-student newspapers were also important within the Chicano movement. Houston’s Compass was a militant paper that aimed to "remind Mexican-American citizens of their rights, to show them how they are being abused, to create the desire to effect changes, and to approach and criticize government agencies." El Grito del Norte served "the Hispano and Indian people of northern New Mexico by presenting news of their struggle for land and justice, in particular news not released by the Establishment papers." El Malcriado, "the farm workers' newspaper," was published by the UFW in Spanish, English, and Tagalog and reached over 10,000 readers.

The Chicano Press Association was established in 1969 as a way for Chicano newspapers to share their content in a similar way to the Underground Press Service. In The Chicano Generation: Testimonios of the Movement, Raul Ruiz writes that, though the group was informal and had no official staff, their annual meetings validated the importance of the underground press to the national Chicano community.

“Our role was to report the news from the Chicano perspective,” Ruiz writes. “We never believed in giving both sides of a story. The Los Angeles Times, for example, would never print the Chicano community’s side of the story. So our task was to balance the Times. This was our mission. This is what the Chicano Press Association was all about.”(Ruiz)

GI-Antiwar Newspapers

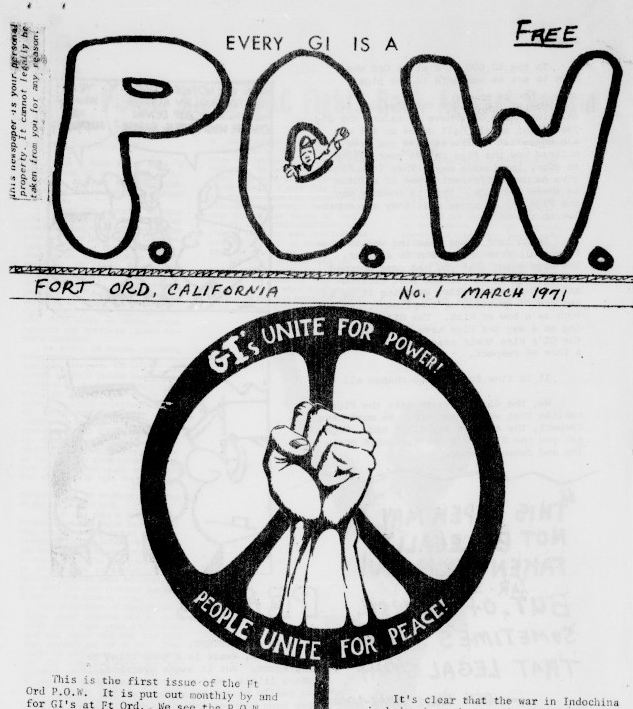

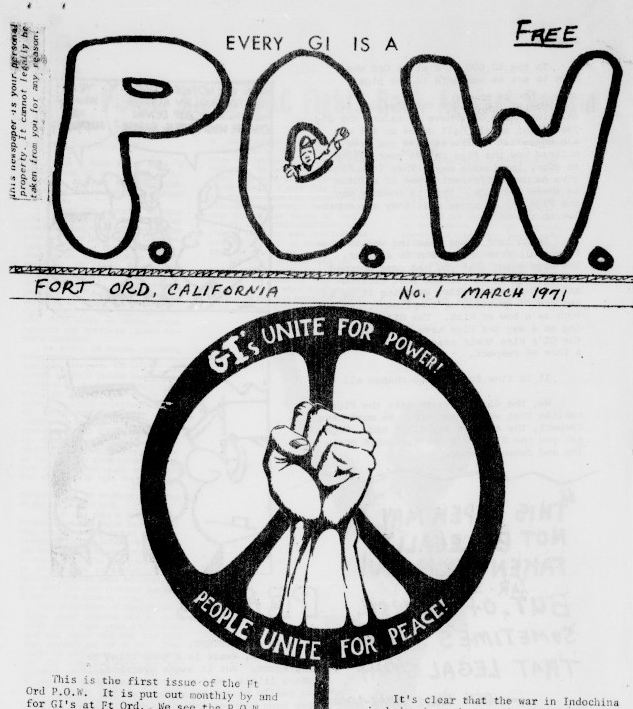

Every GI is a POW was one of hundreds of undergrounds that appeared near military bases, this one at Fort Ord in California during 1971 and 1972

Every GI is a POW was one of hundreds of undergrounds that appeared near military bases, this one at Fort Ord in California during 1971 and 1972

Active-duty GI’s produced antiwar newspapers around the country and world, sharing advice on life in the military, draft resistance, and desertion. In the Pacific Northwest, the McChord Air Force Base and the Fort Lewis Army Base were home to Counterpoint, Fed Up, the Lewis-McChord Free Press, and G.I. Voice. Newsletters like B Troop News, First of the Worst, and How Btry Times were also published at Fort Lewis. Sacstrated was published at Fairchild Air Force Base near Spokane. Puget Sound Sound Off was published at the Washington peninsula’s Bremerton Naval Yard by local members of the Concerned Officers Movement.

As Jessie Kindig notes, GI coffeehouses provided space for GI’s to discuss political opinions, share antiwar sentiments, and produce underground newspapers. Support from civilians and off-base activists helped GI’s produce newspapers despite threats of disciplinary action. However, papers published by GI’s usually did not survive for more than a few years, due to the rapid turnover of active-duty soldiers at each base. (Kindig)

These papers were not limited to military bases located in the U.S.; GI’s stationed in Canada, Europe, and Asia also shared antiwar sentiments through underground papers. Though most focused on news at each base, some also circulated among local civilians and shared news of antiwar demonstrations involving both groups. Civilian antiwar newspapers were also published in all corners of the world: Hawaii Resistance Notes published news of antiwar efforts by students and GI’s, the Australian paper Peace Plans shared antiwar political philosophies, and the Swiss paper Equality discussed the effects of international armed conflict.

Women’s Liberation Periodicals

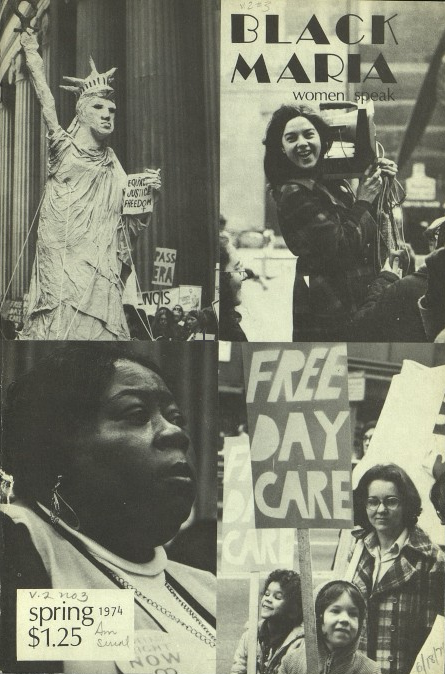

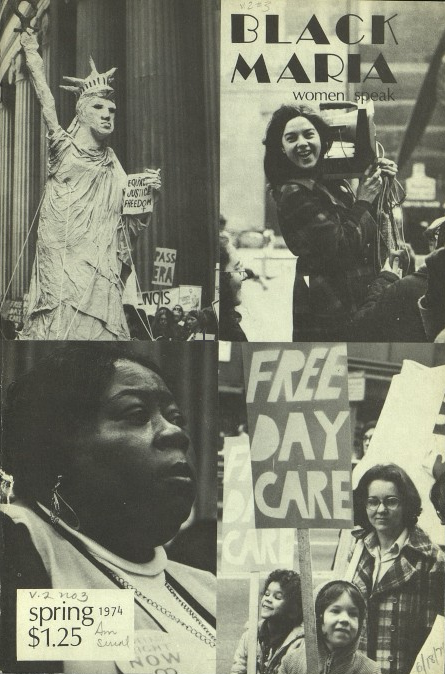

Published by a feminist collective in Chicago, Black Maria was unusually durable, lasting from 1971 to 1983.

Published by a feminist collective in Chicago, Black Maria was unusually durable, lasting from 1971 to 1983.

Though the underground press was largely dominated by men at the beginning of the movement, feminist newspapers eventually grew in number. The Underground Press Syndicate passed several resolutions at their 1969 conference that prohibited sexualized advertisements, mandated that papers publish articles on women’s liberation, and said women should have equal responsibility in a newspaper’s staff. (Glessing)

Three women’s liberation papers that achieved large circulation numbers were Chicago’s Majority Report, Washington, D.C.’s Off Our Backs, and Baltimore’s Women: A Journal of Liberation, each of which had about 20,000 readers. Majority Report contained news articles and information about feminist events, and its writers took no political stances. Off Our Backs discussed women's liberation and reprinted readers' prose, poetry, and artwork about reproductive health care, homosexuality, marriage, and more. Women: A Journal of Liberation discussed topics such as derogatory advertising, male chauvinism, and the portrayal of women in children's books.

Like the rest of the underground press, women’s liberation newspapers were topically and geographically diverse. Women and Art published opinion pieces and interviews about female artists, their work, and competition with male artists. Country Women was "a feminist country survival manual and creative journal" that discussed resistance to gender roles, the unique challenges faced by women in rural communities, and economic independence. Battle Acts was published by Women of Youth Against War & Fascism and discussed child labor, prisons, and global antiwar activism by women. The underground press allowed people in the women’s liberation movement to share a wide variety of ideas throughout the country.

Conservative Alternative Press

The Left was not alone in turning to underground newspapers to share ideas. Conservative and religious groups also published small newspapers, sometimes in the same cities as more radical leftist publications. In Brooklyn, for example, Awake! discussed connections between current events and the Bible.

Other conservative papers from this era include the National Program Letter, a newsletter published in Arkansas that reached 50,000 readers and opposed socialism, communism, and student dissent. The New Guard was published in Washington, D.C., by Young Americans for Freedom, the largest conservative youth organization in the country. The California branch of Young Americans for Freedom also published Creative Californian in Glendale. Some, such as Western Voice, opposed the more liberal teachings of the Catholic Church, such as those related to immigration and draft resistance. In a similar way to the papers published by the Left, conservative and religious groups could discuss current events and provide alternative perspectives to the mainstream press.

Conclusion

Today’s social media echoes the underground press’ ability to mobilize activism and build new movements. Just as today’s activists can easily create their own websites, blogs, and social media pages, almost anyone could publish an underground paper with its own content and style. Zines, which have remained popular to this day, allow people to self-publish their writing, photography, and art using their own production and distribution methods. Both online and offline, today’s writers maintain the spirit and do-it-yourself methods that made the underground press movement successful.

The underground press allowed civil rights groups, feminist groups, antiwar GI’s, and students to directly challenge the established media and provide supporters with a more complete picture of their movements and tactics. Though many publishers faced harassment from police, university administration, and even their own families, the underground press proved to be one of the most widespread and interconnected movements of the Vietnam War era.

Works cited:

- García, Mario. The Chicano Generation: Testimonios of the Movement. Oakland: U of California, 2015. Print.

- Glessing, Robert J. The Underground Press in America. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1970. Print.

- Kindig, Jessie. “GI Papers at Fort Lewis.” Antiwar and Radical History Project – Northwest. Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Projects, 2008. Web.

- “Liberation News Service Records.” Special Collections and University Archives. UMass Amherst Libraries. Web.

- McMillian, John. Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press and the Rise of Alternative Media in America. New York: Oxford UP, 2011. Print.

- Petrov, Aleksandar. Russian Underground Poetry. 3rd ed. Vol. 55. Norman: Board of Regents of the U of Oklahoma, 1981. Print.

- Stone, I.F., Jack Newfield, Nat Hentoff, and William Knustler. “LNS.” Liberation News Service [New York, NY] 21 Sept. 1972. Print.

- Wachsberger, Ken. Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press, Part 2. East Lansing: Michigan State University, 2012. Print.

|

In one of its early issues, the Berkeley Barb celebrated the "Greatest Anti War Protest." (October 22, 1965)

In one of its early issues, the Berkeley Barb celebrated the "Greatest Anti War Protest." (October 22, 1965) The Kudsu, published in Mississippi in 1968, took its name from the upiquitous vine that spreads through the forests of the South, and proclaimed "A New Spirit is Rising in the South."

The Kudsu, published in Mississippi in 1968, took its name from the upiquitous vine that spreads through the forests of the South, and proclaimed "A New Spirit is Rising in the South." Students and ex-students from Michigan State University in Lansing had published an underground named The Paper beginning in 1965. In 1969, it was mysteriously renamed Goob Yeak Geribal

Students and ex-students from Michigan State University in Lansing had published an underground named The Paper beginning in 1965. In 1969, it was mysteriously renamed Goob Yeak Geribal Published in Detroit from 1965 to 1967, Free Poems Among Friends was one of a large number of literary undergrounds.

Published in Detroit from 1965 to 1967, Free Poems Among Friends was one of a large number of literary undergrounds.

Based in San Franciso, Black Dialogue published articles, essays, fiction, poety, and reviews by African American writers. It's last issues appeared in 1970.

Based in San Franciso, Black Dialogue published articles, essays, fiction, poety, and reviews by African American writers. It's last issues appeared in 1970..png)

Every GI is a POW was one of hundreds of undergrounds that appeared near military bases, this one at Fort Ord in California during 1971 and 1972

Every GI is a POW was one of hundreds of undergrounds that appeared near military bases, this one at Fort Ord in California during 1971 and 1972 Published by a feminist collective in Chicago, Black Maria was unusually durable, lasting from 1971 to 1983.

Published by a feminist collective in Chicago, Black Maria was unusually durable, lasting from 1971 to 1983.