by Cameron Molyneux

The ILWU broke away from the International Longshoreman's Association (ILA) in 1937 to join the CIO. The Pacific Coast District of the ILA had waged an 83 day strike in 1934, closing all the ports up and down the West Coast and winning employer recognition for locals that had been without bargaining rights since the 1920s. Led by militants who defied orders from ILA headquarters, the 1934 victory had set the West Coast longshore workers on a different path from the rest of the ILA well before the 1937 split.

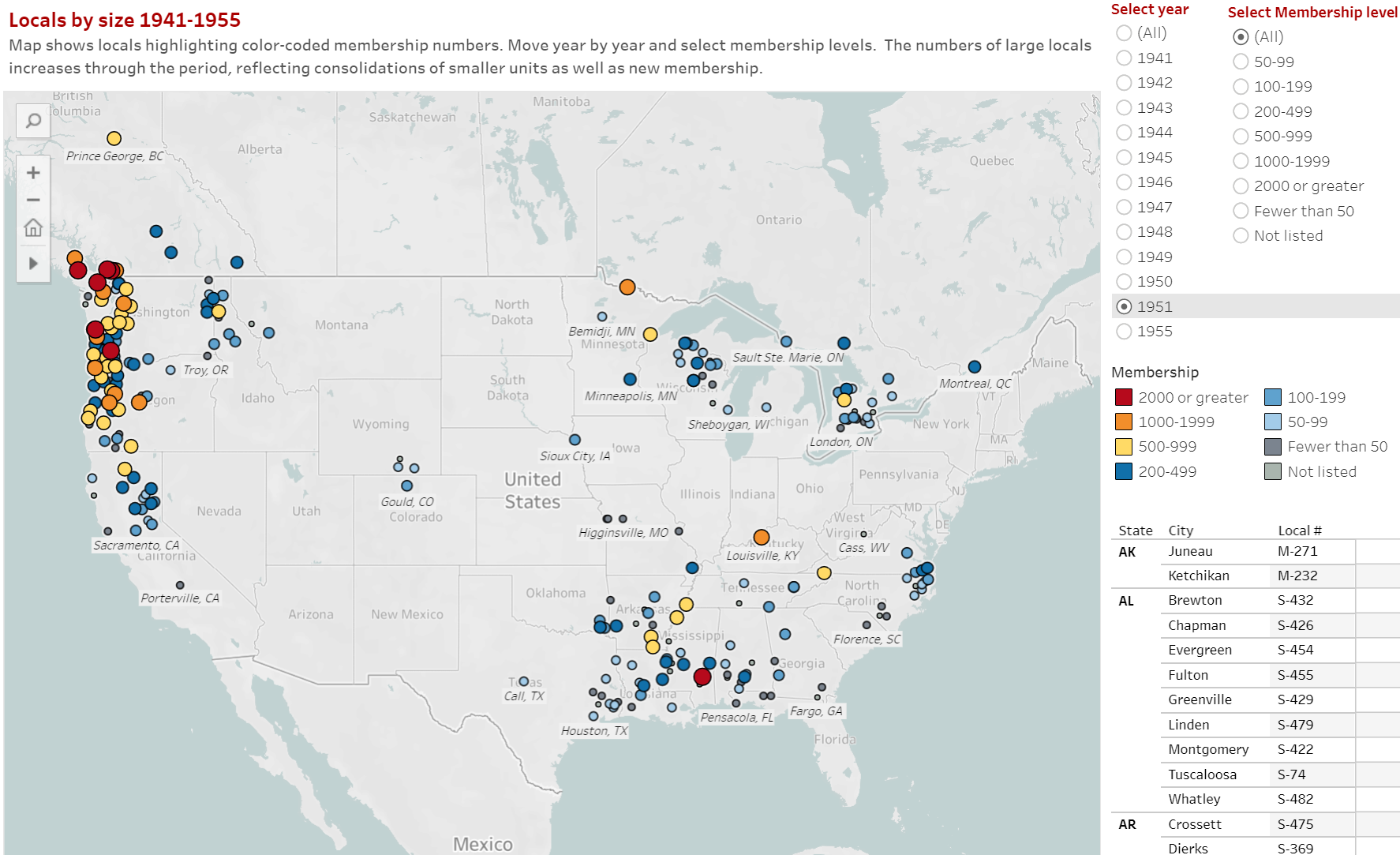

Harry Bridges, leader of the radical faction in the 1934 strike, became the first President of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU-CIO). Over the next 12 years, the union would organize or solidify longshore locals along the entirety of the West Coast while starting successful organizing drives among farm workers in Hawaii and warehouse workers both on the West Coast and states further east. During this period, the union’s membership more than doubled, from 25,000 to 65,000 dues paying members. Like the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers (UE), the ILWU would become famous for its left-wing leadership and progressive rank and file membership. Harry Bridges became a major player within the CIO, serving for several years as the organization's West Coast Director. The ILWU became the base for West Coast organizing drives in other maritime trades as well as the campaign in the timber and sawmill towns that launched the International Woodworkers of America (IWA-CIO).

The union's radical leadership became a source of strength and controversy. The federal justice department said that the Australian-born Harry Bridges was a Communist and made four separate attempts to deport him. He won in court and he also maintained the loyalty of ILWU members, including those who had little sympathy for Communism. That solidarity helped the union survive the red scare and the Taft-Hartley Act. Refusing to expel Communists from leadership positions as required by law, the union was thrown out of the CIO in 1950 and faced vicious persecution. But unlike UE which lost most of its members, the ILWU stayed strong and was able to help and incorporate other persecuted unions, adding locals from the International Fisherman and Allied Workers of America (IFAWA) and the Filipino-led Alaska Cannery Workers Union in 1950.

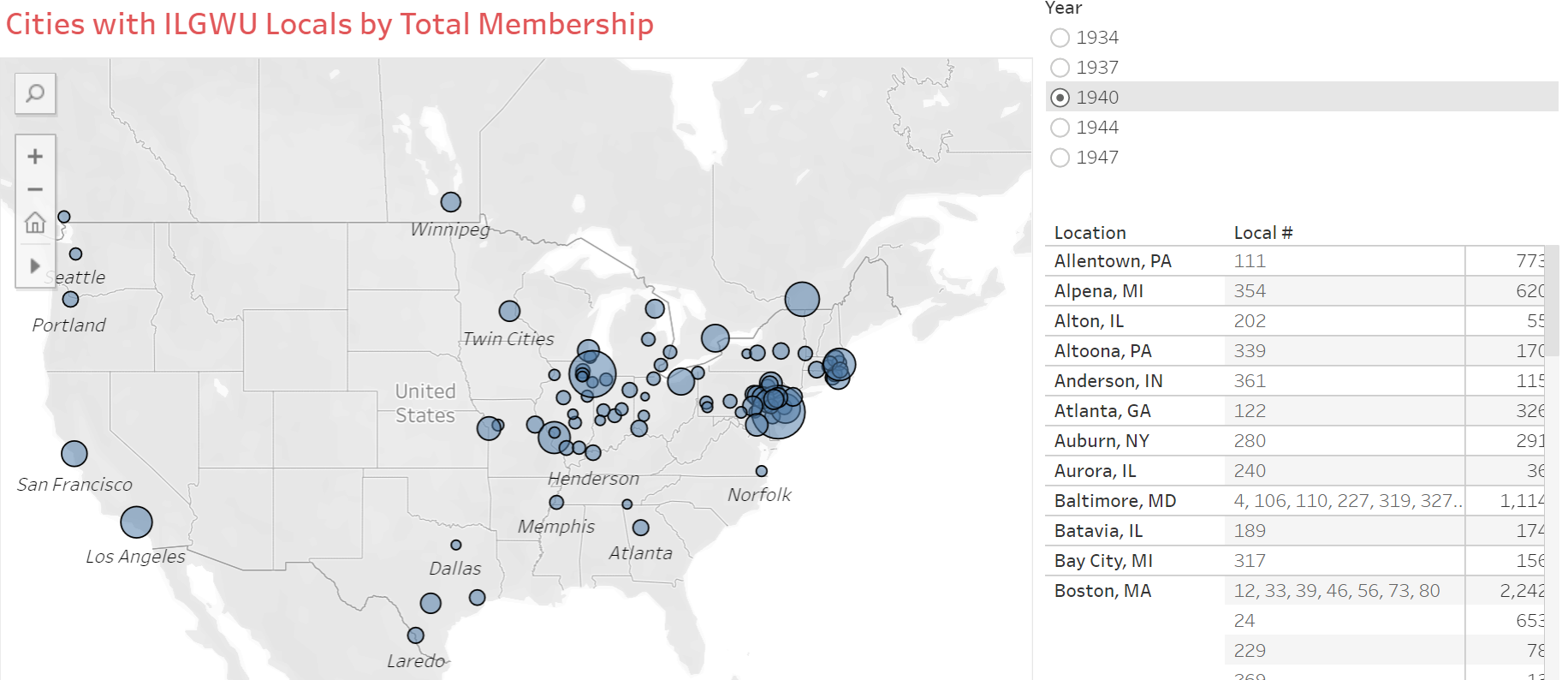

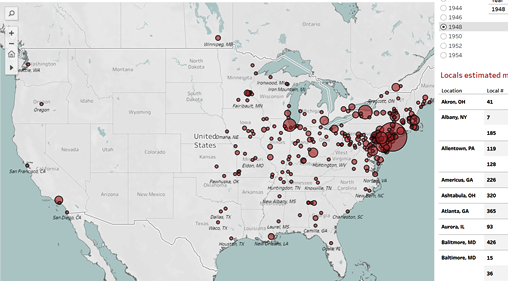

The maps are hosted by Tableau Public and may take a few seconds to respond. If slow, refresh the page.

Move between four maps and charts using the tabs below

Sources: The data for these maps and lists were compiled from roll call documents in the convention proceedings of the Pacific Coast District of the ILA (1934, 1935, 1936) and convention records of the ILWU for 1937, 1938, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1943, 1945, 1947, and 1949, as well as per capita payment ledgers for 1945 and 1946 and a voter turnout database (all provided courtesy of Robin Walker and the ILWU Archive). Data for the total membership chart are taken from Leo Troy’s Trade Union Membership, 1897-1962 (New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1965).

Clarification: Membership numbers on the first map of locals are reported as a range, giving an approximate number. This is due to the way in which votes are allocated in convention roll call; 100 members is equal to one vote and any significant fraction past that earned the local another vote (e.g. 101 members equals two votes). Though some years the ILWU reported exact membership numbers for locals, we have chosen to use ranges for all the years on the map to maintain consistency. The maps charting total membership by city and by state use a combination of the voting formula method and the exact numbers reported, giving some years a rounder number and others a specific number. Please note that convention roll call documents overlooked some locals in various years, most likely because no delegates were sent to the convention or perhaps of dues delinquency.

Research and data compilation: Cameron Molyneux

Maps: Cameron Molyneux and James Gregory

Additional CIO maps and charts

|

|

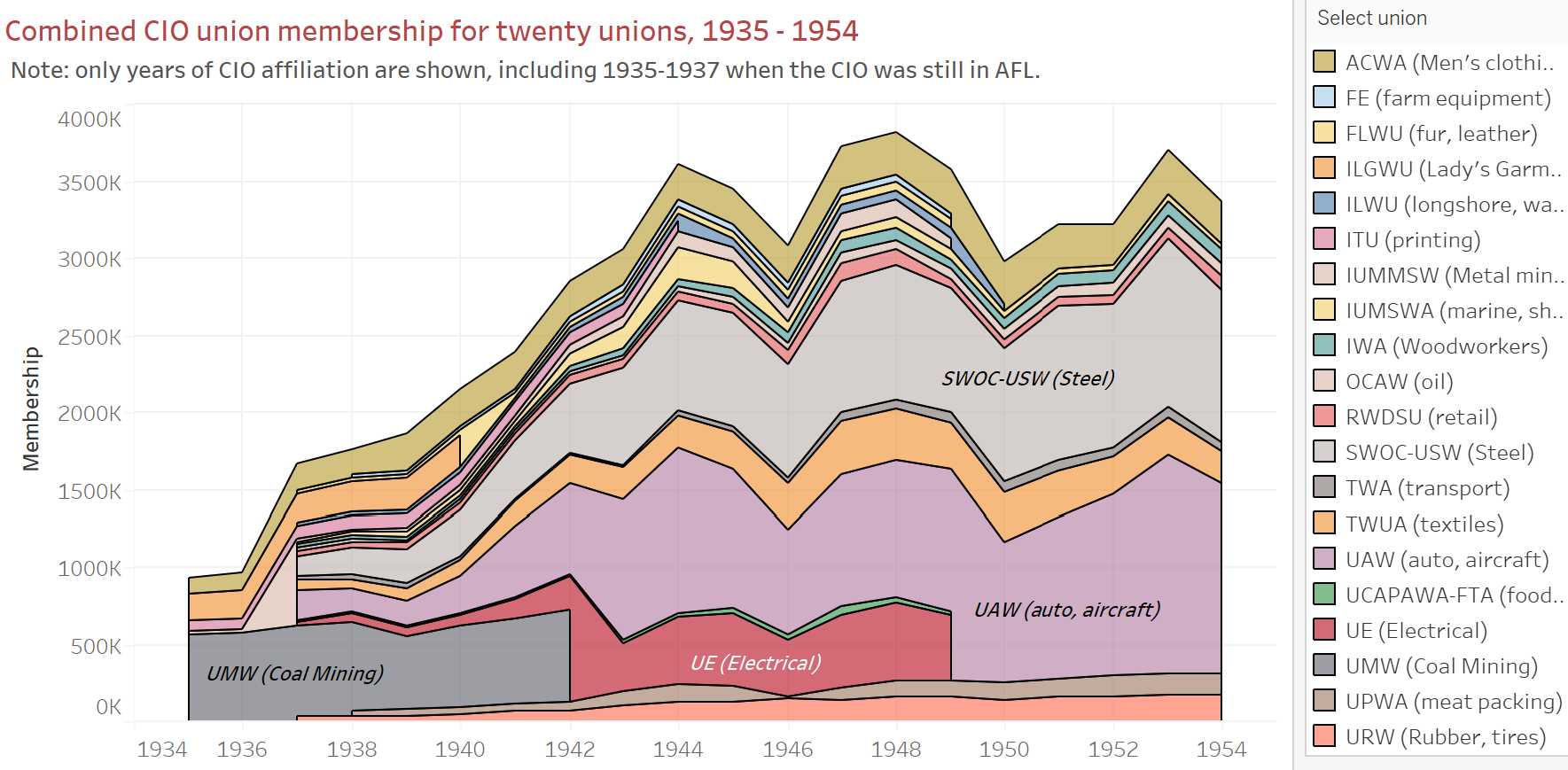

The CIO transformed American labor and American politics. Defying the American Federation of Labor's commitment to craft unionism, the Committee for Industrial Organization was launched in 1935 by leaders of the United Mine Workers and other AFL unions who embraced industrial union organizing strategies. The goal was to build unions in core industries like steel, auto, aircraft, electrical appliances, meat packing, tires, and textiles that had blocked organizing efforts at every turn. Here we start with growth and changes in twenty international unions and then map the locals and membership totals for seven of them, showing the spread of locals and membership density in hundreds of cities for these key unions: United Auto Workers (UAW), United Electrical Workers (UE), Amalgamated Clothing Workers (ACWA), International Ladies Garment Workers (ILGWU), International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), International Typographical Union (ITU), and International Woodworkers of America (IWA). |

|

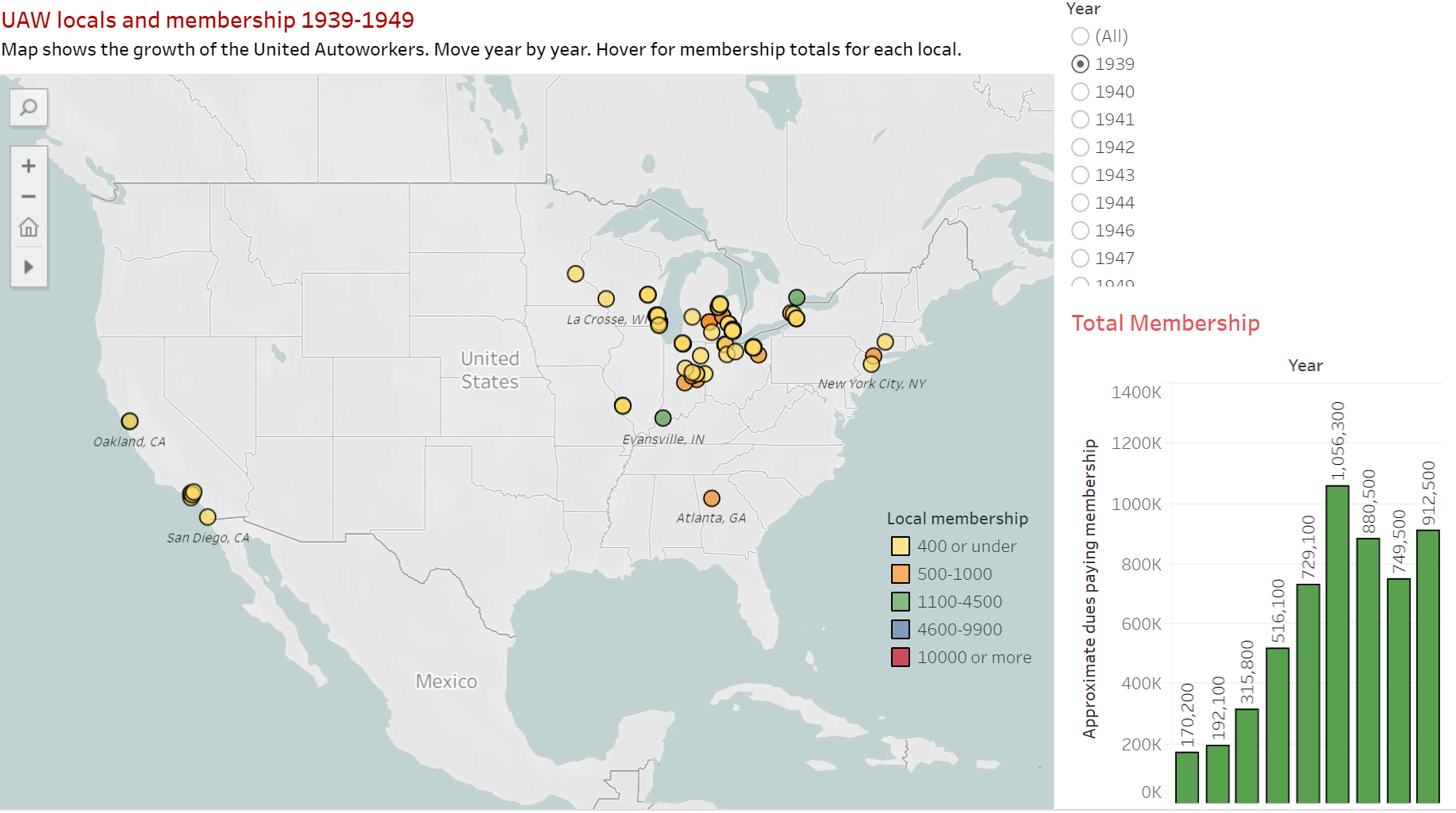

Founded in 1935 as one of the first initiatives of the industrial union organizing committee led by John L. Lewis, the United Autoworkers won a breakthrough victory against General Motors in the dramatic Flint Michigan sit down strike in the winter of 1936-1937. After General Motors agreed to bargain, Chrysler and several smaller auto companies followed suit and by mid-1937 new union claimed 150,000 members and was spreading through the auto and parts manufacturing towns of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. These maps chart the spread of the UAW from April 1939 when it counted 172 locals and about 170,000 members to 1944 with 634 locals and more than one million members then though the late 1940s when conversion to civilian production and a post-war recession caused a dip in membership even as the number of locals increased. Watch the UAW spread across the map in the 1940s, anchored in Michigan and the Great Lakes states but claiming dozens of locals in the Northeast and California, and a sprinkling in Alabama, Geogia, and Texas. |

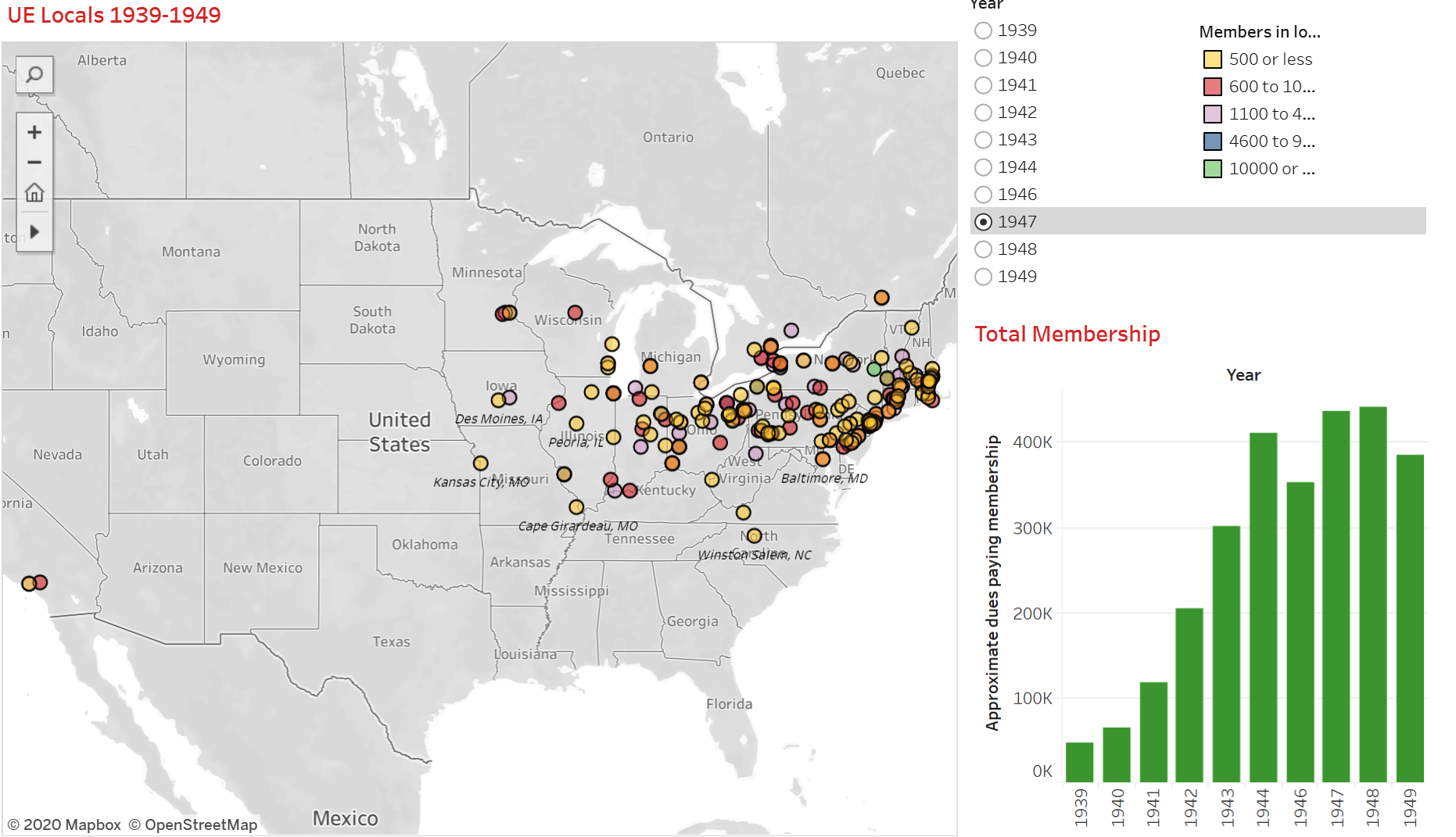

Founded in 1936 by workers from General Electric, Westinghouse, Philco, RCA and other companies that made electrical appliances and machinery, UE soon became one of the largest and most controversial unions in the CIO, claiming a peak membership of 686,000 in 1944. UE was known as a left-wing union, many of its top leaders closely associated with the Communist Party. This had various implications in the early years. The union took strong positions on racial and gender equality. Women were important part of the work force and by the end of the war comprised about 40% of the membership. At the same time, the leftwing reputation left the union vulnerable to red-baiting, which nearly destroyed the union in the early 1950s. Here are five interactive maps and charts showing the year by year geography of the UE. |

Founded in 1900 in four East Coast cities by a workforce largely comprised of immigrants who had prior trade union experience in Europe, the ILGWU was one of the first female majority unions in the American Federation of Labor. As one of the AFL’s few industrial unions, the ILGWU joined the Committee for Industrial Organizing in 1935 as a founding member. But opposed to what they saw as rising communist influence in the CIO, ILGWU leaders left and reaffiliated with the AFL in 1940. Already well-established before joining the CIO, the ILGWU did not experience the same explosion in membership that new unions like the UAW and UE experienced in the later 1930s and 1940s. Despite this, the union maintained steady growth after 1935 and peaked at around 380,000 members in 1947. |

The Amalgamated Clothing Workers was founded in 1914 by immigrant Socialist garment workers who split from the United Garment Workers (UGW), a conservative and cautious craft union affiliated with the American Federation of Labor. It was no surprise that the Amalgamated became one of the seven founding unions when the Committee for Industrial Organization was launched in 1935. And in 1937 when the industrial unions were expelled from the AFL, the Amalgamated became part of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) with Sidney Hillman serving as Vice-President of the newly chartered Congress. |

The ILWU broke away from the International Longshoreman's Association (ILA) in 1937 in order to join the CIO. The Pacfic Coast Division of the ILA had waged a three-month long strike in 1934, closing all the ports up and down the West Coast and winning employer recognition for locals that had been without bargaining rights since the 1920s. Led by militants who defied orders from ILA headquarters, the 1934 victory set the stage for the 1937 split. Over the next 12 years, the newly independent ILWU would solidify longshore locals along the entirety of the West Coast while starting successful organizing drives in farming in Hawaii and warehouses both on the West Coast and states further east. During this period, the union’s membership more than doubled, from 25,000 to 65,000 dues paying members. |

Founded in 1852, the ITU had helped launch the American Federation of Labor in 1886 and remained one of the most progressive unions in the Federation until leaving to start the CIO in 1937. A bastion of consistency and model of successful collective bargaining, the ITU played a unique role in the early CIO. With locals in 658 cities in 1937, the union was able to win the 40-hour week for members and other protections that set aspirational standards for other unions. Its wide geography meant that ITU members were positioned to help in the organizing campaigns of other CIO unions. That remarkable geographic spread is demonstrated in these maps. And at first glance the ITU’s membership barely seems to expand over the course of the 1940s. |

The union's history began in the Pacific Northwest timber strike of 1935. The failure of the AFL-affiliated United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners to respond to its members’ demands led to lumber and sawmill unionists splintering from the craft union to form the Federation of Woodworkers. A year later, the new union affiliated with the CIO as the International Woodworkers of America. Initially based mostly in Washington and Oregon, the IWA expanded rapidly in numbers and geography. With 35,000 members in 1941, the IWA claimed 94,000 a decade later. Although locals were established in the forests of the Midwest and South, much of the growth was in British Columbia, where Chinese-Canadian organizer Roy Mah and South Asian organizer Darshan Singh Sangha led efforts to organize non-white workforces around the Canadian province. |