Sources: Svenska Socialisten(1914-1918) (digital copies University of Minnesota)

Class struggle and sectarianism:

A story of the Scandinavian Socialist Federation

by Love Karlsson

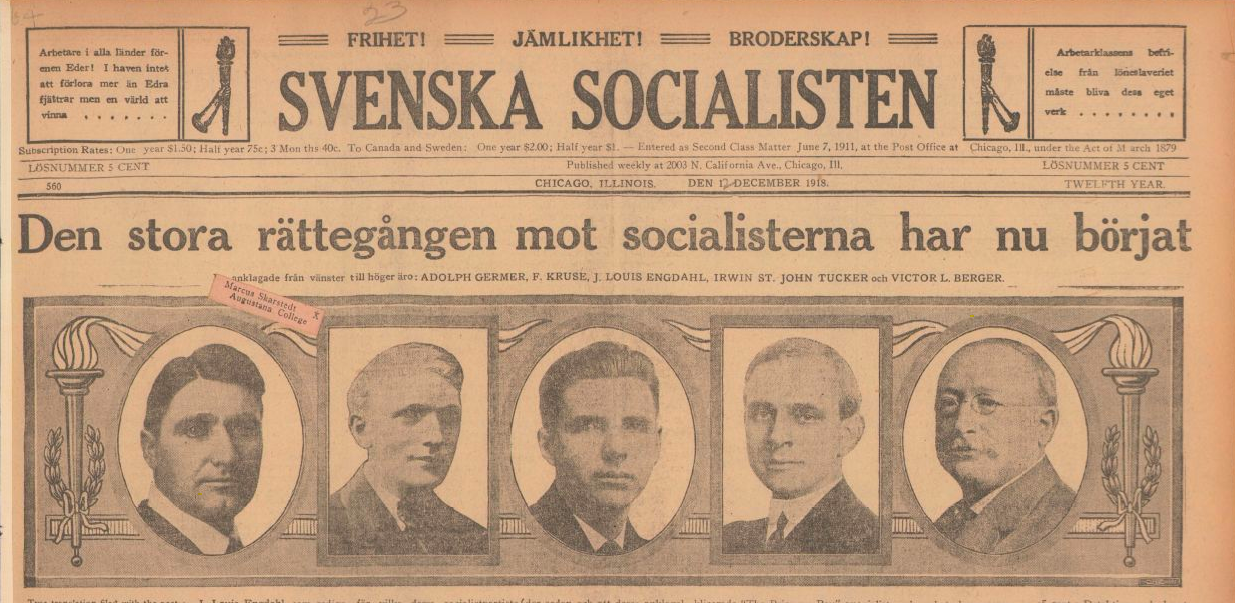

Svenska Socialisten, December 12, 1918. This issue focused on the upcoming trial of five Socialist Party-leaders.In

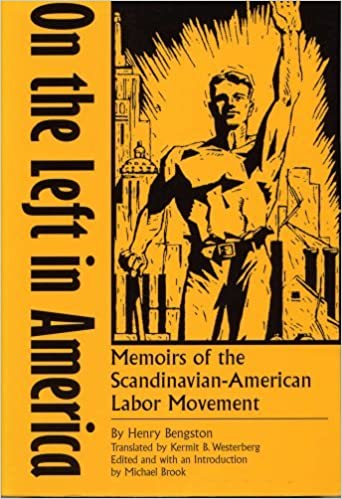

the last chapter of his 1955 book, On

the Left in America: memoirs of the Scandinavian-American labor movement, Henry Bengston starts with the rather bleak sentence: ”It is open to question

whether even the memory of the Swedish-American labor movement will survive the

present generation, and one can ask whether the explanation is to be found in

the biases of those who, up to now, have done historical research on Swedish

America”[1]. The

book, based on Bengston’s personal experience and

extensive interviews, tries to summarize the fascinating history of the

Scandinavian labor movement in the United States. While covering many aspects

of the history of Scandinavian labor, it

pays considereable attention to the internal bickering and ideological differences

that would come to divide the Scandinavian Socialist Federation (SSF) that

Bengston belonged to. This article shares that focus. It is based both on

Bengston’s book and on the collection of

Swedish-American newspapers that have been uploaded online by the Minnesota

Historical Society, amounting to 300,000 newspaper pages in total. When quotes

are included, I have translated them myself.

Svenska Socialisten, December 12, 1918. This issue focused on the upcoming trial of five Socialist Party-leaders.In

the last chapter of his 1955 book, On

the Left in America: memoirs of the Scandinavian-American labor movement, Henry Bengston starts with the rather bleak sentence: ”It is open to question

whether even the memory of the Swedish-American labor movement will survive the

present generation, and one can ask whether the explanation is to be found in

the biases of those who, up to now, have done historical research on Swedish

America”[1]. The

book, based on Bengston’s personal experience and

extensive interviews, tries to summarize the fascinating history of the

Scandinavian labor movement in the United States. While covering many aspects

of the history of Scandinavian labor, it

pays considereable attention to the internal bickering and ideological differences

that would come to divide the Scandinavian Socialist Federation (SSF) that

Bengston belonged to. This article shares that focus. It is based both on

Bengston’s book and on the collection of

Swedish-American newspapers that have been uploaded online by the Minnesota

Historical Society, amounting to 300,000 newspaper pages in total. When quotes

are included, I have translated them myself.

The

Swedish-American socialist milieu initially consisted primarily of individuals

with left-wing sympathies who worked within English-speaking organizations.

”Old man’’ David Westerberg, was one of the pioneers. Born in 1825, according

to his obituary in the Swedish-American newspaper Svenska Amerikanaren,

he moved to Paris as a young man to apprentice as a shoemaker. There he joined

Socialist circles, but decided that it had become unsafe after bullets fired by

Napoleon III’s soldiers crashed into his living room ceiling during the coup of

1851. He relocated to London. He lived for a time in the house of Karl Marx, a

place where people such as Friedrich Engels and Wilhelm Liebknecht were also

residing. He spent another eleven years in Hamburg then moved to New York in

1882 where he helped create the first Swedish socialist organization on

American soil and in the process became a venerated figure of the movement [2].

Henry Bengston belonged to a younger and larger generation of immigrant radicals who created organizations embedded in Scandinavian American communities. Bengston was born on March 27, 1887 in the rural region of Värmland, Sweden. According to historian Emory Lindquist, Bengston stood out among the children of the village due to his intellectual leanings. As a young man in Sweden, he became a temperance activist and a Good Templar-member. He also developed an intellectual interest in the Social-Democratic movement through becoming acquainted with it’s literature, but since there was no Social-Democratic organization in his area, he remained a sympathizer not a member. In 1907, he like many other Swedes traveled to North America in order to seek his fortune. He did so together with his uncle, a liberal who later would come to denounce his nephew’s socialist ideas. Bengston got involved in the Swedish-American Socialist movement in a lumber camp outside of Ontario, Canada in 1908, where he encountered both Swedish socialists and copies of the Socialist newspaper Arbetaren. Within a year he moved to Chicago where he joined Socialist Party, specifically its Scandinavian Socialist Federation. He would rise in the federation’s ranks quickly and in 1912 he was offered a position as editor of its main paper, Svenska Socialisten. He would stay as editor until 1920, when he sided with the minority faction of the federation in opposing the turn towards communism. After leaving the federation, he worked for many decades as a publisher in Chicago. Even though he stuck to his Socialist ideals for the rest of his life and maintained a friendship with most of his comrades from before the split, he did not work actively in politics again. He did, however, write several pamphlets and books on the history of the Scandinavian-American labor movement before passing away in 1974.[2b].

Competing Radical Movements

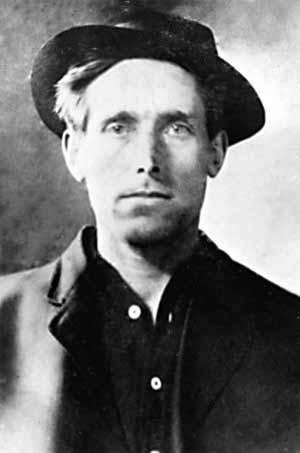

Joel Emmanuel Hägglund adopted the name Joe Hill after immigrating from Sweden in 1902. In 1910 he joined the IWW and soon became known for the clever songs he wrote for the Little Red Songbook. An itinerant organizer for the IWW, he was arrested in Utah in 1914 and charged with murder. Convicted and executed by firing squad despite questionable evidence, he became the Wobbly's most famous martyr. This essay focuses on the Scandinavian Socialist

Federation, which was affiliated with the Socialist Party and would become the

biggest organization for Socialist Scandinavians from the early 1900s until

1920. However, many of the earliest Swedish socialist groups were affiliated

with the Socialist Labor Party, the party that Westerberg initially belonged to.

Others joined or the Industrial Workers of the World, the syndicalist oriented

revolutionary union movement that operated to the left of both the SP and SLP.

Bengston writes that many Swedes who had been politically active in their home

countries would join organizations in the U.S that had similar political ideas

to their old ones. Social

Democrats would typically join the Socialist Party, syndicalists and more

radical ”Young Socialists’’ would go into the IWW and the still more

independent-minded would form anarchist groups. All of these organizations

competed for members and attention in the many Scandinavian enclaves and

networks spread across the United States.

Joel Emmanuel Hägglund adopted the name Joe Hill after immigrating from Sweden in 1902. In 1910 he joined the IWW and soon became known for the clever songs he wrote for the Little Red Songbook. An itinerant organizer for the IWW, he was arrested in Utah in 1914 and charged with murder. Convicted and executed by firing squad despite questionable evidence, he became the Wobbly's most famous martyr. This essay focuses on the Scandinavian Socialist

Federation, which was affiliated with the Socialist Party and would become the

biggest organization for Socialist Scandinavians from the early 1900s until

1920. However, many of the earliest Swedish socialist groups were affiliated

with the Socialist Labor Party, the party that Westerberg initially belonged to.

Others joined or the Industrial Workers of the World, the syndicalist oriented

revolutionary union movement that operated to the left of both the SP and SLP.

Bengston writes that many Swedes who had been politically active in their home

countries would join organizations in the U.S that had similar political ideas

to their old ones. Social

Democrats would typically join the Socialist Party, syndicalists and more

radical ”Young Socialists’’ would go into the IWW and the still more

independent-minded would form anarchist groups. All of these organizations

competed for members and attention in the many Scandinavian enclaves and

networks spread across the United States.

The most famous Swedish-American radical, the labor musician and organizer Joe Hill, was a member of the IWW. His execution in Salt Lake city in 1914 made him into a martyr of the socialist movement and his songs would spread and be widely celebrated. Even though he belonged to a competing organization, the SSF honored Hill and the federation’s choir in Chicago was even named after him. In Svenska Socialisten, he was often referred to as Joseph Hillström, one of his Swedish names, perhaps as a way to to take pride in and highlight the shared national bond. According to Bengston, a small group of SSF-members were the only people present outside of the prison walls as Hill was executed . The group had often visited him during his imprisonment and wanted to be there as one last gesture of solidarity.[3b].

This

often led to conflicts, even in cases where the groups competing could be

perceived to be ideologically close. In a 1916 issue of the Swedish-language

IWW-affiliated newspaper Allarm, described a debate between the leader of

the Swedish anarchist group Revolt and the IWW-supporters in the ”Joe

Hill Club’’ of Chicago. Revolt leader Theo Johnson accused the IWW of

promoting their own organization at every single opportunity and of tiring

everybody with constant mentions of ”those three letters’’. The IWW writer

countered that he had purchased an issue of Revolt’s self-named newspaper

and that the word ”Revolt’’ was used no less than 45 times[3]. However, the IWW members

could perhaps have benefitted from a newspaper name like Revolt, as the

choice of Allarm would come back to haunt them. During the 1918 wave of

anti-IWW repression, one of the Swedes arrested was convicted in court partly

because he had sent an telegram to the office of the newspaper saying ”Sänd

Allarm’’ (send Allarm). Instead

of being interpreted as an obvious request for copies of the newspaper, the

jury accepted the prosecutors’ claim that it meant ”Send all arms’’ and was the

beginning of an armed insurrection[4]. The

fight between Revolt and IWW could be seen as an example of how groups

that could be assumed to have a common goal would be divided by sectarianism.

This

was also evident from the fights between the Swedish section of the Socialist

Labor Party and the Scandinavian Socialist Federation that was allied with the

Socialist party. In a back and forth

exchange in an Svenska Socialisten issue from 1917, the SLP sympathizer

Carl Iverson attacks the SSF in an letter to the editor. In one part, he calls

the leaders of the SP ”Wolves in sheep’s clothes, and as such much more

dangerous than the open defenders of capitalism’’. The Svenska Socialisten editors responds with harsh words, claiming that the SLP was rightfully known

as ”the small and quarrelsome SLP’’ and that it’s newspapers publish ”true dirt

journalism’’. The rest of their response builds on their typical critique of

SLP for being too authoritarian[5]. Another

example of the tension between the SSF and the SLP is a 1911 incident in the

Chicago suburb of Pullman, where workers built Pullman railroad cars. A Swedish

pastor-turned-socialist named Sibiakoffsky was supposed to speak in the town’s

Swedish assembly hall in order to help establish a club for the newly founded

SSF. But at the time of the meeting, he discovered that the hall was filled

with SLP members who already had

established a club of their own in Pullman and intended to stop their rivals

from doing the same. They did so by disrupting the speaker with constant

heckling. In the end, the organizing efforts of the SSF in Pullman were halted

and the bitterness between the two parties increased.[6]

The

conflict can be traced back to the foundation of the two parties. The Socialist

Labor Party was the older one, founded 1877 in Newark, New Jersey by socialist

immigrants, many from Germany. The party’s multi-ethnic composition would

define it for decades. According to Bengston, only 10 of the 26 newspapers

supporting the party in 1877 were English-speaking, while 14 were German[7]. The

party’s Swedish section had their own paper called Arbetaren (The

Worker). In its very simply designed first edition from 1890, it declares its

goal to be to "Raise the reputation of Swedes and from the best of our

ability work to improve the economic conditions for our Swedish workers’’[8]. The

party was led by Daniel De Leon, who made the party follow his own sectarian

version of Marxism called Marxist-De Leonism [9]. According to the

Swedish-American proletariat-poet Arthur Landfors, at the time he joined the

SLP in 1912 every prospective member had to swear an oath saying that they

believed the Socialist Labor Party to be the only party in America that was

furthering the socialist agenda[10].

Bengston says of his personal friend but political adversary Gustaf Björk that ”his

greatest pleasure was to assail members of the Socialist Party” and that ”he

considered it a matter of personal honor to convert SP:ers to the one and only

doctrine of salvation, the Socialist Labor Party's”[11].

Björk’s

story can also serve as an example of how many Swedes became involved in the

American labor movement. Like many young Swedes, Björk had been active in the

Social Democratic movement in Sweden. When he arrived in Chicago, his political

background helped him create connections and find his place in the new country.

Before leaving the country, he had been given the address to a boarding house

owned by a woman named Mrs Molberg, a house that served as an informal

headquarter for Swedish SLP members and was the first stop in the new country

for many of them. In the house, they got to know other socialists. Loyalty to

the party-doctrines was also somewhat of a requirement to live there. Björk would

later become a communist who traveled to the newly founded Soviet Union several

times.

The

Socialist Party equivalent of the Mrs Molberg boarding house was another home

in Chicago that would be a hub for its party’s Swedish section. That was the house of a Mrs. Dawn. After the brothers and trade unionists John and Carl Dawn

emigrated from Sweden in the early 20th century, they soon brought over their 10 siblings

and widowed mother. After Mrs. Dawn learned about her sons newfound socialist

beliefs, she became a socialist herself. She opened up her home for members of

the party and remained a labor activist for the rest of her long life [12].

Chicago

The delegates of the first Scandinavian Socialist Federation-Congress in 1910 (Svenska Socialisten, July 2, 1920).

That

Chicago was the center of both Scandinavian Socialist sections was not a

coincidence. Between 1850 and 1930 roughly 1 million Swedes had moved to the

U.S, with around 20% of the Swedes in the world living in the country at one

point[13].

Chicago was the center of the Swedish-American population. It was known as

‘’The second biggest city in Sweden’’ due to having a larger Swedish-born

population than Gothenburg, the city that historically has been the second

biggest in Sweden[14]. Even

if only a smaller number of Swedish-Americans shared socialist beliefs, it

added up to a relatively large number of people for organizations to recruit.

The delegates of the first Scandinavian Socialist Federation-Congress in 1910 (Svenska Socialisten, July 2, 1920).

That

Chicago was the center of both Scandinavian Socialist sections was not a

coincidence. Between 1850 and 1930 roughly 1 million Swedes had moved to the

U.S, with around 20% of the Swedes in the world living in the country at one

point[13].

Chicago was the center of the Swedish-American population. It was known as

‘’The second biggest city in Sweden’’ due to having a larger Swedish-born

population than Gothenburg, the city that historically has been the second

biggest in Sweden[14]. Even

if only a smaller number of Swedish-Americans shared socialist beliefs, it

added up to a relatively large number of people for organizations to recruit.

The

Socialist Party that the Dawn family supported was in contrast to the smaller

and more exclusive Socialist Labor Party a broad coalition of groups that had

come together in order to create what would become the largest socialist

political party in U.S history. It was founded during a ‘’Unity Convention’’ in

Indianapolis 1901 by a variety of people from smaller parties such as the

Social Democratic Party and the Populist Party[15]. Jack Ross mentions in his

book ‘’The Socialist Party of America’’ that the party’s Finnish

federation was one of the first immigrant sections in the party and that it

also was one of the most influential with a large following[16]. This could be seen as

somewhat surprising in light of the fact that Finland’s population was small

compared to the other Nordic countries, who organized together. However,

Bengston also testifies that the Finnish were the only ones who were organized

in Ontario, the first place that he moved to in America, but adds that they

struggled to gain influence outside of their own circles due to the big differences

in language that made learning English tougher for them[17].

The

Swedes, Danes and Norwegians initially created separate clubs that were not

connected through an overarching network. The Norwegians created a group in

Chicago 1904, a Scandinavian socialist singing society was created in 1906 (it

would survive until 1940) and the Danes created the ‘’Karl Marx Socialist

Club’’ in 1907[18].

Chicago would also be the location of the only Scandinavian Socialist Assembly

hall in the U.S. It was named ‘’Folkets hus’’ (the house of the people) as

similar places traditionally were and still are called in Sweden to this day[19].

According to Bengston, there were three socialist clubs outside of Chicago that

were affiliated with the Socialist Party prior to 1910: A Danish-Norwegian one

in Kenosha Wisconsin, a Swedish in Duluth, Minnesota and another Swedish in

Rockford, Illinois[20].

The

city of Rockford was a smaller version of Chicago, with a massive Swedish

population that dominated the eastern part of town. It was the birthplace of

the SSF Swedish newspaper ‘’Svenska Socialisten’’ and some of the town’s

Swedish Socialists would create national controversy by collectively dodging

the draft during World War 1. Bengston considers the Rockford group to have

been ‘’the strongest federation section’’[21]. The federation itself was,

however, created on the initiative of the Chicago groups, who in 1910 called

for a convention of SP-affiliated Scandinavian groups. The convention was held

in Chicago and gathered 12 Swedish delegates and 20 Danish and Norwegian. The

English-speaking mother party was represented by party secretary J. Mahlon and

J. Louis Engdahl, editor of the American

Socialist[22].

Scandinavian

Socialist Federation

The

Scandinavian Socialist Federation would organize in a similar manner to the

English speaking sections, with the main difference being that they used the

Scandinavian languages to reach workers that did not feel comfortable enough

with English to organize in the regular sections. Bengston’s book includes the

membership statistics from the start of the federation in 1911 up until the

year it disassociated from the Socialist Party in 1920. I have picked out the

statistics of the first year, the peak year and the last year to give an idea

of its size during its existence.

Scandinavian Socialist Federation

Clubs Members

1911 7 216

1918 68 3,735

1920 68 2,584[23]

The

federation grew in numbers as a result of the Great Swedish strike of 1909,

during which business owners blacklisted a large number of radical workers who

had to move out of the country in order to find work. Bengston says of his

friend Rickard Edwinson ”He remained faithfully at his post throughout the

strike, but when the conflict was resolved, he found, as did so many other

trade unionists, that his name had been blacklisted by the Swedish Employers'

Federation, which usually was a guarantee of permanent unemployment. Edwinson

chose to follow the example of other strike victims by immigrating to America.

In November 1909, he arrived with his family in Chicago and reclaimed his right

to employment’’[24]. One

of the first Swedish Socialist campaigns that Bengston encountered in Chicago

was a fund raising drive for strikers in Sweden, which shows that

American-Scandinavian activism could be transnational[25].

Pacific

Northwest

During the 1916 Socialist Party presidential campaign, Scandinavian Federation members joined the regular SP local in Bellingham, Washington to equip this ’’Red car’’, to campaign for SP candidate Allan Benson in the towns of Whatcom County. 18 Socialist Party members toured the area, 12 of them belonging to the Swedish club. 5000 Benson-flyers were distributed with the car every week. 100 subscribers were recruited to the North-West Worker, an SP weekly published in Washington State while 69 subscribed to the Swedish language newspaper (Svenska Socialisten, October 5, 1916). The

Pacific Northwest with its large Scandinavian population was another natural

hotspot for the SSF. A search for ‘’Seattle’’ in the MNHS newspaper archive

brings up 174 issues of ‘’Svenska Socialisten’’ in which the city is

mentioned. On the 12th of November 1916, the Washington state SSF clubs held a

district-convention in Bellingham. 10 delegates represented 5 clubs, with

Spokane being absent. The Washington clubs had 196 members in total, 56 of them

in Hoquiam. Most of the convention’s decisions concerned administrative

matters, but one large point of order was a condemnation of the violence

against IWW workers in Everett that recently had resulted in five deaths in what

became known as the Everett Massacre. The correspondent wrote that: ‘’The SSF district-conference /.../ has after

a careful study of the capitalist-violence in Everett against members of the

I.W.W. on the sunday of november 5th decided to declare our strongest objection

to the horrifying brutality and carelessness of the state. /.../ We stand

unconditionally on the side of the wronged workers (without completely

accepting the principles of the I.W.W) and we want to contribute with both our

moral and economical support to the workers that have been detained’’. The

conference ended its meeting with four hurrahs for the imminent success of the

Washington district and international socialism[26]. A half year later, the

organizational effort of the Scandinavian Socialists in response to the Everett

event was described in another issue of Svenska Socialisten. In the same

way that Scandinavians organized separately in the Socialist Party, they had created

their own organization for collecting funds to support the IWW men on trial for

murder. It was called the ‘’Scandinavian Defense Committee’’ and was connected

to the main organization, ‘’The Workers International Defense League’’. Its

membership was a mixture of SSF and IWW members. In the end, it had managed to

collect 300 dollars for the accused Wobblies through meetings and theatrical

plays, and members reported that the organization had acted as a platform for

building stronger bonds across organizational lines in the

Scandinavian-socialist milieu in Washington[27].

During the 1916 Socialist Party presidential campaign, Scandinavian Federation members joined the regular SP local in Bellingham, Washington to equip this ’’Red car’’, to campaign for SP candidate Allan Benson in the towns of Whatcom County. 18 Socialist Party members toured the area, 12 of them belonging to the Swedish club. 5000 Benson-flyers were distributed with the car every week. 100 subscribers were recruited to the North-West Worker, an SP weekly published in Washington State while 69 subscribed to the Swedish language newspaper (Svenska Socialisten, October 5, 1916). The

Pacific Northwest with its large Scandinavian population was another natural

hotspot for the SSF. A search for ‘’Seattle’’ in the MNHS newspaper archive

brings up 174 issues of ‘’Svenska Socialisten’’ in which the city is

mentioned. On the 12th of November 1916, the Washington state SSF clubs held a

district-convention in Bellingham. 10 delegates represented 5 clubs, with

Spokane being absent. The Washington clubs had 196 members in total, 56 of them

in Hoquiam. Most of the convention’s decisions concerned administrative

matters, but one large point of order was a condemnation of the violence

against IWW workers in Everett that recently had resulted in five deaths in what

became known as the Everett Massacre. The correspondent wrote that: ‘’The SSF district-conference /.../ has after

a careful study of the capitalist-violence in Everett against members of the

I.W.W. on the sunday of november 5th decided to declare our strongest objection

to the horrifying brutality and carelessness of the state. /.../ We stand

unconditionally on the side of the wronged workers (without completely

accepting the principles of the I.W.W) and we want to contribute with both our

moral and economical support to the workers that have been detained’’. The

conference ended its meeting with four hurrahs for the imminent success of the

Washington district and international socialism[26]. A half year later, the

organizational effort of the Scandinavian Socialists in response to the Everett

event was described in another issue of Svenska Socialisten. In the same

way that Scandinavians organized separately in the Socialist Party, they had created

their own organization for collecting funds to support the IWW men on trial for

murder. It was called the ‘’Scandinavian Defense Committee’’ and was connected

to the main organization, ‘’The Workers International Defense League’’. Its

membership was a mixture of SSF and IWW members. In the end, it had managed to

collect 300 dollars for the accused Wobblies through meetings and theatrical

plays, and members reported that the organization had acted as a platform for

building stronger bonds across organizational lines in the

Scandinavian-socialist milieu in Washington[27].

Scandinavian

radicals were also active in the Seattle General Strike that captured world

headlines in February 1919. In an account published in Svenska Socialisten a month later, Oscar W. Larson describes his travels in Washington state during

the great strike and his efforts to organize the Scandinavian workers. In

Tacoma, he organized a smaller rally that was overshadowed by the ones of two

competing Swedish Labor organizers present in the city at the same time. In

Seattle, he noted that the workers were highly disciplined, doing their utmost

to not give the police any reason to shut the strike down with force. The

meeting he organized there drew a larger crowd, and he noticed with pleasant

surprise that even the Syndicalists and the SLP:ers abstained from criticizing

him and that the crisis seemed to have brought all the groups closer together.

He proceeded to hold two meetings in Bellingham, where it previously had been

hard to have continuous political activity due to the constantly changing

conditions of the lumber trade that the Swedish workers were employed in. From

one of the few long-time activists, he received a small bust of Karl Marx that

impressed him so much that it made him suggest that it should become a part of

every socialists home. After short organizing detours to Mt Vernon and Everett,

he went back (‘’by automobile’’) to Seattle where a large-scale meeting for

Scandinavians was held. At the meeting, demands for an new industrial

labor-organization to replace the AFL were raised and Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson

was condemned. Finally, before arriving in Portland, he helped organize a new

club in Rochester with 45 Swedish speaking Finns[28].

World

War I

When

the United States entered World War I in Spring 1917, the political climate

became more complicated for radicals, especially immigrant radicals. Most

members of the Socialist Party opposed American participation in the war and

some, like SP leader and presidential candidate Eugene Debs, were sent to

prison for violating new federal laws that made it a crime to speak against or

interfere with the war effort. Socialist newspapers were subject to censorship and

were often banned from the mail service. The party’s foreign-language press

faced the toughest scrutiny. The government forced Svenska Socialisten and other foreign language newspapers to send

all articles about the war to the post office to be translated before they

could be published. Bengston was the editor of the Svenska Socialisten at

that time and he was personally interrogated by postal inspectors. Several

issues were also confiscated in their entirety, which created economic

difficulties for the paper and forced the editors to self-censor in order to be

allowed to continue. Svenska

Socialisten co-editor, Seattle native Nils R Swenson, was arrested and at

one point the paper was required to publish an ad for ‘’liberty loans’’

supporting the war. In doing so, the editors incurred severe criticism from

some SSF members and even more from the SLP. In the end, the government

strangulation of the radical press made the Svenska Socialisten a

financial burden that could not properly communicate the ideas of its

publishers[29].

The

level of repression also increased for regular members. Svenska Socialisten contributor

‘’Allen’’ describes his attempts to organize workers for the SSF in Butte,

Montana in an 1919 issue. When he arrived in the town, he was disappointed to

discover that the majority of the Scandinavian miners previously living in the

area had left due to the low salaries and that the remainder already were

organized in the IWW. The police followed him wherever he went for a couple of

days before they kicked him out of Montana and ordered him not to come back[30].

Breakup

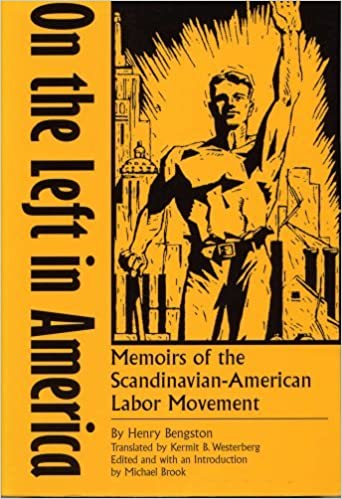

Originally published in Swedish in 1955, Henry Bengston's memoir was translated and reissued in English in 1999In

the summer of 1919, the Socialist Party of America split in two in response to

the Russian Revolution. The leaders of the new Soviet Union called upon

socialists around the world to affiliate with the Communist International under

the leadership of the Russian Bolshevik Party. Socialist parties in most

countries were shattered as their most radical members bolted and launched new

Communist Parties. In the United States the majority of Socialist Party members

sided with the revolutionaries and that was even more the case in the language

federations, including the leadership and most of the membership of Scandinavian

Socialist Federation[31]. The Svenska

Socialisten reported that a ‘’Left-wing conference’’ met in New York on

the 10th of July 1919 in the course of which the ‘’Suspended

language-sections’’ and the

state-organization of Michigan proposed to create a new communist party. The

idea was opposed by the majority, who wanted to try to reclaim the Socialist

Party for the revolutionary left[32].

Originally published in Swedish in 1955, Henry Bengston's memoir was translated and reissued in English in 1999In

the summer of 1919, the Socialist Party of America split in two in response to

the Russian Revolution. The leaders of the new Soviet Union called upon

socialists around the world to affiliate with the Communist International under

the leadership of the Russian Bolshevik Party. Socialist parties in most

countries were shattered as their most radical members bolted and launched new

Communist Parties. In the United States the majority of Socialist Party members

sided with the revolutionaries and that was even more the case in the language

federations, including the leadership and most of the membership of Scandinavian

Socialist Federation[31]. The Svenska

Socialisten reported that a ‘’Left-wing conference’’ met in New York on

the 10th of July 1919 in the course of which the ‘’Suspended

language-sections’’ and the

state-organization of Michigan proposed to create a new communist party. The

idea was opposed by the majority, who wanted to try to reclaim the Socialist

Party for the revolutionary left[32].

The

divide was present on both an national and a local level and could be highly

confusing and demoralizing for members that had worked together for a long time

and now found themselves on opposite sides of the conflict. In an report from

the SSF Rockford section, a member is quoted as saying ‘’Here I’ve been telling

people about politics for ten years and encouraged them to vote for the

Socialist Party. I have told them that this Party is the only one that can save

the country - And now our own organization has left it and two new parties who

calls themself communist have been formed. It does not look good from the

outside at all’’.

The

Rockford writer of the report partly agrees, but also writes that: ‘’That is

the way of life. The one who can not keep up with the new times will have to

stay where he is at. Going back is no longer possible, and concerning the

division, it is a little bit like in a family. The kids grow up and learn about

new ideas that the parents can not understand and that they will, sometimes

violently, try to stop them from engaging with. The word division should

actually no longer be used, as it has been a positive developmental step

forward for the movement’’ [33].

The

Scandinavian Socialist Federation dissolved in the factional turmoil of 1919

while a new and smaller Scandinavian Language Federation joined the Communist

Party. The individual activists of the SSF went in a wide variety of directions

after its demise. Oscar W Larson, the Svenska Socialisten writer who

described his organizing campaign in Washington State during the general

strike, worked successfully as a labor organizer among English-speaking workers

in Salt Lake City before being deported by federal authorities. He would later

become a Social Democratic politician in the Swedish city of Uppsala [34].

Rickard Edwinson, the activist who moved to the U.S after being blacklisted in

the great Swedish strike of 1909 ended up reconciling with the director of the Swedish

Employers' Federation who had done the blacklisting when they both attended the

same banquet in Chicago[35].

Henry

Bengston, who authored On the Left in America: memoirs of the

Scandinavian-American labor movement, remained a socialist, if not as

active as in his early life. In the last chapter of the 1955 book, he notes

with pleasure that the Sweden that he had left due to tough economic conditions

now served as an inspiration to the world with its rather well-functioning

Social Democratic system. He states that he thinks that the U.S should follow

its lead[36].

Joel Emmanuel Hägglund adopted the name Joe Hill after immigrating from Sweden in 1902. In 1910 he joined the IWW and soon became known for the clever songs he wrote for the Little Red Songbook. An itinerant organizer for the IWW, he was arrested in Utah in 1914 and charged with murder. Convicted and executed by firing squad despite questionable evidence, he became the Wobbly's most famous martyr.

Joel Emmanuel Hägglund adopted the name Joe Hill after immigrating from Sweden in 1902. In 1910 he joined the IWW and soon became known for the clever songs he wrote for the Little Red Songbook. An itinerant organizer for the IWW, he was arrested in Utah in 1914 and charged with murder. Convicted and executed by firing squad despite questionable evidence, he became the Wobbly's most famous martyr.  During the 1916 Socialist Party presidential campaign, Scandinavian Federation members joined the regular SP local in Bellingham, Washington to equip this ’’Red car’’, to campaign for SP candidate Allan Benson in the towns of Whatcom County. 18 Socialist Party members toured the area, 12 of them belonging to the Swedish club. 5000 Benson-flyers were distributed with the car every week. 100 subscribers were recruited to the North-West Worker, an SP weekly published in Washington State while 69 subscribed to the Swedish language newspaper (Svenska Socialisten, October 5, 1916).

During the 1916 Socialist Party presidential campaign, Scandinavian Federation members joined the regular SP local in Bellingham, Washington to equip this ’’Red car’’, to campaign for SP candidate Allan Benson in the towns of Whatcom County. 18 Socialist Party members toured the area, 12 of them belonging to the Swedish club. 5000 Benson-flyers were distributed with the car every week. 100 subscribers were recruited to the North-West Worker, an SP weekly published in Washington State while 69 subscribed to the Swedish language newspaper (Svenska Socialisten, October 5, 1916).  Originally published in Swedish in 1955, Henry Bengston's memoir was translated and reissued in English in 1999

Originally published in Swedish in 1955, Henry Bengston's memoir was translated and reissued in English in 1999