by Rachelle Byarlay

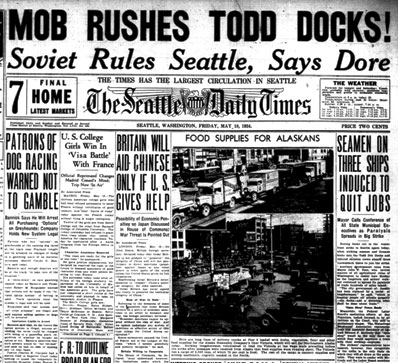

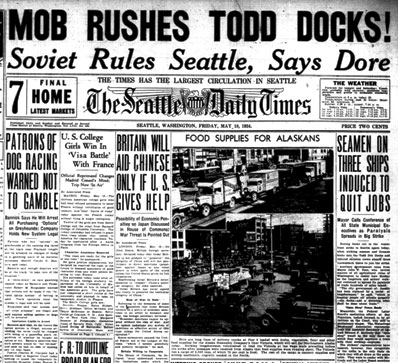

The Seattle Times warns of shortages in this headlined article of May 10, 1934, shortly after the strike began. (Click to enlarge)

The year 1934 saw a wave of strikes that spread across the entire United States. One of the most paralyzing strikes was the waterfront worker’s strike, which froze all major ports up and down the Pacific Coast. It began with a coast-wide longshore strike organized and led by the International Longshoremen Association (ILA). Originally, the ILA demanded higher wages and a shorter workday, but expanded its demands to include ILA recognition by the employers and union control of the waterfront hiring halls. As the strike progressed, it encompassed the entire maritime shipping industry on the West Coast, and made front-page news for the entire two and a half months of the port’s closure.[1]

Through analysis of different Seattle-area newspaper coverage of the strike, we can explore the shifting and varied opinions debating the strike. While the Seattle Daily Times, supported business from the outset, Seattle's other two daily newspapers, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and the Seattle Star, only slanted their coverage against the strike after the outbreak of violence when strikers confronted non-union workers hired by the employers. Meanwhile, the Communist Party's Voice of Action, a weekly newspaper, loudly supported the strike, providing one of the few media outlets through which the strikers could articulate their perspectives and demands. The views of the public, as influenced by the media, were crucial to the outcome of the strike.[2]

From the beginning, the Seattle Times focused on the closing of the docks and the negative impacts of the strike on Seattle’s businesses. On May 9, 1934, the first day of the strike, the first and only article that the Times published bore the headline “Longshoremen Out on Strike; Shipping Withheld.” Rather than leaving it at “Longshoremen Out on Strike,” the newspaper immediately brought attention to the strike’s economic effects. This posture was also reflected in the article itself: the opening paragraph reported that the “ship loading and discharging came to a complete halt” with fifteen ships held idle in the waters.[3] Only at the end of the article were the strikers’ grievances mentioned. On May 28th, the day when an agreement to end the strike was proposed, the Times’s business-oriented bias was presented once again with a headline that read “Strike Costing City a Million a Day!” The entire article focused on the monetary losses caused by the strike in Seattle and other West Coast port cities, arguing that the value of products moving through the ports was one million and that the losses to general business were much more. The article went so far as to claim that the strike impeded the state’s economic recovery from the Great Depression, writing “The Chamber’s president laid the stoppage of the Pacific Northwest’s recovery from the depression directly on the strike” and then discussed the loss of businesses such as fishing and lumber mills.[4] In effect, this article placed the burden of all of these problems on the strike.

Siding completely with employers, the Times used sensational headlines to demonize the strikers, this one from May 18.(Click to enlarge) Given the Times’s stance, it is not surprising to find that they lauded police action to break the strike. When the police were brought in on June 20th to force open the ports, the front-page headline read “Forty Police Guard Crews at Pier 40 to Open Port,” and then reported on the unloading and loading of cargo.[5] With so much emphasis on the port’s opening, it is clear to see that the paper was anxious for the strike to end. An editorial titled “Seattle Shall Not Die!” on the front-page of the June 10th edition of the Seattle Times only further proves this point. Encompassing an entire page and marking one of the only times the strike was mentioned in an editorial, the Times called on its readers to answer a very one sided question: “…shall Seattle live like a free city, or shall it be choked to death to satisfy the ambitions of a few labor leaders?”[6] Here, the Times argues that the public comes before labor, reminding people of the failed attempt of Seattle’s general strike in 1919 which they argue held “…[no] regard to the welfare of the whole”.[7] The editorial goes on to state, “The Times has kept its patience as long as humanly possible.”[8] Because labor leaders rejected the first compromise deal, the editorial argued that the union was a threat to the American way of life and that “…[labor leaders] want power and complete dominance of Seattle…”[9] With its placement and its passionate words, it is clear that the author is trying to rally the emotions and support of the readers and sway public opinion away from the strikers. Although not as strong, this pro-business anxiety to end the strike is also evident in the July 31st issue of the Seattle Times, the day the strike ended and the workers returned to their posts, with their return to work described as a “big parade” and the mention of a figure of $200,000,000 in losses from the strike.[10]

The Seattle PI enthusiastically backed the mayor's plan to use police to break the strike in this June 20 edition. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer also mentioned the business losses during the strike, but focused primarily on the freezing of the ports. Economic loss certainly wasn’t the main focus of each headline, but it was a recurring theme of the P.I.’s coverage. In the front-page article of the May 10th issue, the P.I. noted that “business amounting to a million dollars a day in Seattle … is threatened with paralysis.”[11] This paralysis was mentioned again and again throughout the weeks of the strike. On May 13th, the P.I. reported that “sweeping along the waterfront” was “a mob of striking longshoremen” that “paralyzed Seattle shipping.”[12] On May 29th, the paper reminded its readers again of the strike’s effect, “paralyzing shipping since May 9th.”[13] After this point however, like the Times, the P.I. began to focus on the idea of opening the ports, as shown on June 21st when a headline read “City Officials Unite with Employers in Plan to Open Port Today” and discussed the “[opening] of the Port of Seattle to commerce.”[14]

Usually the most liberal of Seattle's three daily newspaper, the Seattle Star offered no support to the strikers and called for both sides to end the conflict. (July 2, 1934)The Seattle Star appeared to be relatively uninterested in the economic effects of the strike until after the multiple failures of the employer/labor negotiations, mentioning the port’s closing only during the first days of the strike.[15] On May 28th, however, we begin to see the shift in attitude as an editorial takes the place of headlines and bemoans the “desperate situation” of Seattle and her economy.[16] Two days later, columnist “J. R. Justice” called for ending the strike so that “business may again get down to business.”[17] The next day, Justice asked for intervention by President Roosevelt, arguing that “the paralysis of business has gone too far and should be ended.”[18] Even if Justice was only one columnist, the views of the strike in his columns went unchallenged in the Star’s pages, influencing public opinion in its one-sided reportage. Needless to say, on July 31st, the Star was jubilant about the return of the longshoremen and other waterfront workers, announcing that “ships that have been lifeless at anchor for weeks are moving into the docks.”[19] It is the closing sentence of the headline article that best summed up the jubilant mood: “The first load is out. The strike is over.”[20]

Published by the Communist Party, the weekly Voice of Action condemned employers and police and called for a General Strike in support of the longshoremen. ( June 22, 1934) Unlike the Seattle Times, Post-Intelligencer, and Star, the Voice of Action barely made any mention of the loss of business in the two and a half months of the strike. The only mention of the loss to business was in the context of lauding the strike’s power: a May 15th article titled “Strikers Sweep Docks Clean of Scabs” saw workers “marching on eleven piers” who “tied up all shipping.”[21] Clearly, the strike’s effect on commerce was no matter to the Voice of Action. This newspaper was trying to rally together the workers and maintaining their solidarity.

Despite their focus on the negative loss to business, the Seattle P.I. and the Seattle Star were very neutral about their portrayal of the waterfront employers, contrasting with the pro-business Seattle Times and the pro-labor Voice of Action. In the Post-Intelligencer, the front-page article on the events of the first day of the strike discussed a variety of topics, including the workers’ demands, those who supported the strikers, the loss of the ports, and the employers’ appeal to the longshoremen, offering them a chance to return before they hired new men in their place.[22] On May 13th, the day after the strikebreaker’s raid, the P.I. again took a neutral stance toward the employers in a front-page article. The P.I. reported that employers had requested aid from the National Guard, a request Seattle Mayor Dore had felt it to be unnecessary. In Dore’s words, “the strikers aren’t going to run Seattle, but neither are employers.”[23] On a similar note, after the rejection of the first proposal, columnist J. R. Justice did not blamed both parties equally for its failure, arguing that “if employers and employees could only get it in their heads that they are partners in business, both would be better off in the end.”[24]

Seattle PI cheers the end of the strike (July 30, 1934) The Seattle Times, however, was always supportive of the employers, if not outright sympathetic. In the first article on the strike, the Times printed only the words of the employers, while the P.I. made sure to also give the union leaders a chance to represent their views.[25] The day following the strikebreaking raid, the Times published an article with the headline “Mob Drives Workmen from Piers and Ships,” in which the opening paragraph was dedicated to employers’ attempts to open their ports while they ask for protection from the National Guard.[26]

In addition, the Times allowed the publication of waterfront employer propaganda in their newspaper, the only paper out of the four studied here to print these notices. Two days after the launch of the strike, the Times printed a notice from the waterfront employers to the longshoremen publicly threatening to bring in strikebreakers if the longshoremen don’t return to work. The employer’s notice made sure to close ominously by “urging” them to come back “before it’s too late.”[27] A second notice was printed on May 27th during the negations for an agreement to end the strike. Clearly a propaganda piece, the notice lays out claims from the “union” versus “the truth” as written in the Waterfront Dispatching Hall records—really were just unsupported rebuttals to the union claims. Through these arguments, the employers tried to guide the reader toward a negative answer to the question they posed: “Is this strike justified?”[28]

Caption If one asked the editors of the Voice of Action what their answer to this question was, they would loudly proclaim “NO!” Voice of Action saw their job as supporting the strike, maintaining the solidarity of workers, and encouraging support for labor from the public. This meant portraying employers almost as if they were villains in a comic book. In an article on the strikebreaker’s raid, the Voice of Action made note of a worker who had been fired by employers for his sympathies with the strikers.[29] In another article on the May 28th agreement, the Voice of Action wrote of its suspicions that employers were hiring more “scabs”—non-union workers brought in to break the strike—to help launch two stalled ships, claims that were unsubstantiated.[30] The Voice of Action’s expressed hatred reached a climax at the end of the strike: the August 3rd article, entitled “Maritime Strikers Betrayed, Undefeated,” accused the employers of blacklisting strikers who returned to work. The article also blamed the “sell out” strike agreement on employers’ strongarm tactics, claiming that the strike was only broken because of “maneuverings with the employers.”[31]

Unlike the Voice of Action, which fully supported the workers, both the Seattle P.I. and the Seattle Star were neutral in their attitude toward the strikers, while the Seattle Times didn’t take them seriously at first. As the strike progressed, however, all three mainstream papers began to shift their coverage against the workers, the Times being the most critical of the three. The tirelessly pro-worker stance of the Voice of Action, then, is not surprising, as it acted as a counterweight to the mainstream coverage.

Too, the Voice of Action was run by the Communist Party, which had a long tradition in American labor history of working to organize unions and worker solidarity, often through strikes.[32] When the strikers raided the men working their jobs on May 20th, the Voice of Action published an article glorifying striker’s actions, entitled “Strikers Sweep Docks Clean of Scabs.” There was a strong emphasis on non-longshore workers’ sympathy with the strikers, noting other maritime trades who joined the strikers “in solidarity with the longshoremen.”[33] As mentioned earlier, after the negotiations on May 28th, the Voice of Action tried to focus on the effectiveness of worker’s efforts in an attempt to keep up their morale.[34] The Voice of Action also made sure to portray the strikers as innocent “citizens” during the accidental gassing of a crowd on June 20th when the police were brought to open the ports and claimed that gassing was an intentional “experiment.”[35]

The Seattle P.I. and the Seattle Star didn’t treat the workers as sympathetically as the Voice of Action, especially as the strike progressed. On May 10th, both the Seattle P.I. and the Seattle Star were rather objective, not selective, in their coverage, reporting on the multiple maritime industries joining the longshoremen’s cause.[36] The Seattle P.I. also made note of the peaceful nature of the strikes on the waterfront, bringing attention to the police chief and his warning to his men that they were not to intervene with “peaceful picketing” and that “extreme patience and caution must be used.” The P.I. even went on to give a statement from the union, something that the Seattle Times never did.[37] The Seattle Star kept this patient attitude all the way through the rejection of the first peace proposal, printing an article written by a striking longshoreman. In it, the longshoremen portrayed himself as an honest family man and an American citizen in an attempt to draw sympathies from the readers. The longshoremen argued that he was striking because he had no other choice: he couldn’t afford to live off of his seasonal wages and support his family any longer.[38]

Unlike the Star, however, the Seattle P.I. quickly shifted directions once the strikebreaker’s raid took place and began to portray the strikers as barbaric men, associating them with the mob, and focusing on their violence towards the strikebreakers. The opening sentence to the front-page article of the May 13th edition of the Seattle P.I. made sure to declare that “sweeping along the waterfront, a mob of striking longshoremen paralyzed Seattle shipping…”[39] It later spoke of striking workers as if they were beasts, reporting that “unrestrained by police, they swarmed, hauling strikebreakers from their work.” In the same article, the P.I. narrated the story of the raid, ship by ship, highlighting the story of a strikebreaker who was thrown into the water and the arrest of two apparently belligerent strikers.[40] It was not until the events of June 20th and 21st that both the Seattle Star and the Seattle P.I. spoke of the strikers negatively because of their violence. In the Star, the strikers are now treated as barbaric intruders to the ports, describing them as they crowded outside of the fence along Piers 40 and 41 “armed with clubs and rocks.”[41] The Seattle P.I. created a similar image, portraying the strikers as dangerous men who could be aroused to violence at any moment like a sleeping beast:

"Moving with the utmost caution, city, country, and state officials cooperating with ship operators and other waterfront employers moved throughout the night and early hours this morning in a…plan to break the strike deadlock…and open the ports of Seattle to commerce."[42]

With this change of direction, it is evident that the members of the P.I. and the Star were weary of the strike and its attendant violence.

The Seattle Times also grew tired of the striker’s violence, but only after they were forced to take the strikers and their demands seriously. On the first day, the strike was mentioned not on the front-page like in other papers but rather on the back of the paper in the “Marine” section. In the article itself, the Times quoted employers speaking of the strikers as if they were wayward children, grandly offering the strikers “a chance to think it over,” and arguing that “a majority of [their] men did not want to strike and were forced into it.”[43] The next day, again in the Marine section, a second article ran, “Strike Breakers on the Seattle Front.” In this article, the strikers were portrayed as benign and jovial as they turned back trucks heading towards the docks, “drivers joking with the men before they drive away.”[44] Like the P.I. and the Star, it was not until the strikebreaker raid that the Times began to take the strikers seriously, associating them with a rioting mob.

On May 13th, the events of the previous day made headline news with the title “Mob Drives Workmen from Piers and Ships.” In the article, the “mob” bled into a “riot” when the Times wrote that “100 policemen battled strike rioters…and several persons on each side were injured.”[45] The image of the riot is carried through to June 20th, the day of the police intervention, when the headline “Police Use Clubs on Dock Rioters” made front-page news. Like the P.I., the Times portrayed the strikers as violent barbaric men, reporting that the “police swinging clubs and striking longshore pickets throwing rocks clashed at Smith Cove this afternoon…”[46] This was actually a part of the opening paragraph, suggesting its importance and setting the tone for the rest of the article. In combination with the other two mainstream newspapers, it is evident that no matter what side the public took in the beginning, newspapers reportage sought to sway opinion against the strikers.

All three of the mainstream newspapers, although some more sympathetic than others at first, eventually shifted and shifted their coverage against the strike. The only newspaper that consistently supported and encouraged them was the Voice of Action, whose goal was to maintain their solidarity and to keep the strike going. The Seattle Times stood against the strike because of its sympathies with employers and in protest of the strike’s negative effects on Seattle’s business. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer and the Seattle Star may have been more objective, but they too in the end had grown weary of the strike’s economic stranglehold. With all three newspapers focusing so strongly on the loss in commerce caused by the strike, the radical Voice of Action had a difficult job winning public opinion. The strike finally ended on July 31, 1934, and it was only through the arbitration in October of that same year that the strikers achieved their goals.

Copyright (c) 2009, Rachelle Byarlay

HSTAA 353 Spring 2009

[1] Magden, Ronald E.. History of Seattle Waterfront Workers 1884-1934. (Tacoma: Tacoma Longshore Book & Res, 1991), p. 201.

[2] Magden, Ronald E.. History of Seattle Waterfront Workers 1884-1934, p. 204.

[3] “Longshoremen Out on Strike; Shipping Halted,” The Seattle Times, May 9, 1934, p. 10.

[4] United Press, “Strike Costing City Million a Day!” The Seattle Times, May 27, 1934, pp. 1, 10.

[5] “400 Police Guard Crews at Pier 40 to Open Port,” The Seattle Times, June 20, 1934, p.1, 8.

[6] “Seattle Shall Not Die!” The Seattle Times, June 8, 2009, p.1.

[7] “Seattle Shall Not Die!” The Seattle Times, June 8, 2009, p.1.

[8] “Seattle Shall Not Die!” The Seattle Times, June 8, 2009, p.1.

[9] “Seattle Shall Not Die!” The Seattle Times, June 8, 2009, p.1.

[10] “All Strikers Return,” The Seattle Times, July 31, 1934, p.1, 5.

[11] “Teamsters Back Longshore Strike of 1500 Men Here,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 10, 1934, p.1, 10.

[12] “2,000 Longshore Strikers Raid 12 Ships; Stop Work; ‘No Troops Now,’ –Martin,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 13, 1934, p.1-2.

[13] “Dock Agreement Reached”, The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 29, 1934, p.1-2.

[14] “City and State Officials Unite With Employers in Plan to Open Port Today,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 20, 1934, p.1-2.

[15] “1,000 Strikers Picket Ships at Wharves,” The Seattle Star, May 9, 1934, p.1, 2; “Shippers Hurls Challenge at Strikers Here,” The Seattle Star, May 10, 1934, p.1, 3.

[16] “Only President Can Break Strike Deadlock,” The Seattle Star, May 28, 1934, p.1.

[17] J. R. Justice, “It Seems to Me,” The Seattle Star, May 30, 1934, p.4.

[18] J. R. Justice, “It Seems to Me,” The Seattle Star, May 31, 1934, p.4.

[19] “Seattle Waterfront Hums as Strikers Return to Work,” The Seattle Star, July 31, 1934, p.1, 2.

[20] “Seattle Waterfront Hums as Strikers Return to Work,” The Seattle Star, July 31, 1934, p.1, 2.

[21] “Strikers Sweep Docks Clean of Scabs,” Voice of Action, May 15, 1934, p.1.

[22] “Teamsters Back Longshore Strike of 1500 Men Here,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 10, 1934, p.1, 10.

[23] Quoted in “2,000 Longshore Strikers Raid 12 Ships; Stop Work; ‘No Troops Now,’ –Martin,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer May 13, 1934, p.1-2.

[24] J. R. Justice, “It Seems to Me,” The Seattle Star, May 30, 1934, p.4.

[25] “Longshoremen Out on Strike; Shipping Halted,” The Seattle Times, May 9, 1934, p. 10.

[26] “Mob Drives Workman from Piers and Ships,” The Seattle Times, May 13, 1934, p.1.

[27] Waterfront Employers of Seattle, “Longshoremen,” The Seattle Times, May 11, 1934, p.9.

[28] Waterfront Employers of Seattle, “To the Longshoremen and the Public,” The Seattle Times, May 27, 1934, p.20.

[29] “Strikers Sweep Docks Clean of Scabs,” Voice of Action, May 15, 1934, p.1.

[30] “Ryan’s Orders Betray Longshoremen,” Voice of Action, May 29, 1934, p.1.

[31] “Maritime Workers Betrayed, Undefeated,” Voice of Action, August 3, 1934, p.1.

[32] Rick Fantasia and Kim Voss, Hard Work: Remaking the American Labor Movement (Berkley: University of California Press, 2004), p. 42.

[33] “Strikers Sweep Docks Clean of Scabs,” Voice of Action, May 15, 1934, p.1.

[34] “Ryan’s Orders Betray Longshoremen,” Voice of Action, May 29, 1934, p.1.

[35] “Cops Try Out Tear Gas in Seattle Streets!” Voice of Action, June 22, 1934 p.1.

[36] “Shippers Hurls Challenge at Strikers Here,” The Seattle Star, May 10, 1934, p.1, 3; SPI; “Teamsters Back Longshore Strike of 1500 Men Here,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 10, 1934, p.1, 10.

[37] “Teamsters Back Longshore Strike of 1500 Men Here,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 10, 1934, p.1, 10.

[38] Dan Clarke, “One of Seattle’s Striking Seamen Tells Why He’s Out,” The Seattle Star, May 30, 1934, p. 2.

[39] “2,000 Longshore Strikers Raid 12 Ships; Stop Work; ‘No Troops Now,’ –Martin”, The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 13, 1934, p.1-2.

[40] “2,000 Longshore Strikers Raid 12 Ships; Stop Work; ‘No Troops Now,’ –Martin,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer May 13, 1934, p.1-2.

[41] “Effort to Load Ships Here Fails,” Seattle Star, June 20, 1934, p.1.

[42] “Police Will Open Port Today!” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 20, 1934, p.1-2.

[43] “Longshoremen Out on Strike; Shipping Halted,” The Seattle Times, May 9, 1934, p. 10.

[44] “Strikebreakers Handle Cargoes at Three Piers,” The Seattle Times, May 10, 1934 p.11.

[45] “Mob Drives Workman from Piers and Ships,” The Seattle Times, May 13, 1934, p.1.

[46] “Police Use Clubs on Dock Rioters,” The Seattle Times, June 21, 1934, p.1, 9.