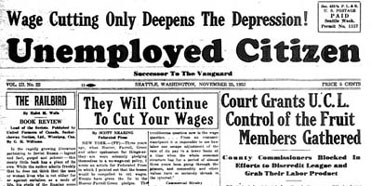

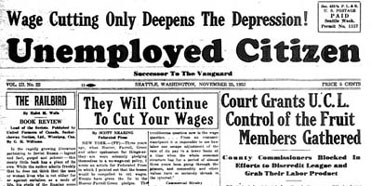

Called the Vanguard when it began publishing in 1930, this monthly newspaper later became the Unemployed Citizen. See the reports below.

Founded in West Seattle in 1931, the Unemployed Citizens League (UCL) became in just a few months an important political force in Seattle and beyond.

The organization had two goals. First, it would establish self-help cooperatives where unemployed men and women could exchange labor. Second, it would develop a political organization that politicians could not ignore. Within months the organization had branches throughout Seattle and nearby cities and claimed a membership in the tens of thousands.

The Great Depression was only a few months old in January 1930 when a new monthly tabloid called the Vanguard appeared on the streets of Seattle. Affiliated with the Seattle Labor College, it was edited by two of the city's best-known labor radicals, Hulet Wells and Carl Brannin, both socialists, but no longer members of the Socialist Party. The Vanguard immediately championed the cause of radical action to address the economic crisis and escalating unemployment. Wary of the Communist Party which had taken the lead in staging jobless protests, the Vanguard spent 1930 and the first half of 1931 reporting on the plight the unemployed while advocating broader goals of democratic socialism.

JULY 1931

UCL branches Read about the individual branches of the UCL in Self-Help Activists: The Seattle Branches of the Unemployed Citizen’s League by Summer Kelly.

It was in July 1931, writes historian Terry Willis, that Wells and Brannin took the first steps towards building a new organization. Reaching out first to neighbors in West Seattle, they organized an initial meeting of the Unemployed Citizens League. The name was brilliant. Right from the start, the organization would emphasize that most jobless people were citizens and, critically, voters. That first meeting was quickly followed by the formation of neighborhood UCL clubs throughout the city, all publicized in the Vanguard. By October, twenty-two neighborhood branches were holding weekly meetings and sending delegates to meetings of the UCL coordinating body, the Central Federation.[1]

Read about the individual branches of the UCL in Self-Help Activists: The Seattle Branches of the Unemployed Citizen’s League by Summer Kelly.

It was in July 1931, writes historian Terry Willis, that Wells and Brannin took the first steps towards building a new organization. Reaching out first to neighbors in West Seattle, they organized an initial meeting of the Unemployed Citizens League. The name was brilliant. Right from the start, the organization would emphasize that most jobless people were citizens and, critically, voters. That first meeting was quickly followed by the formation of neighborhood UCL clubs throughout the city, all publicized in the Vanguard. By October, twenty-two neighborhood branches were holding weekly meetings and sending delegates to meetings of the UCL coordinating body, the Central Federation.[1]

The organization published a list of demands and a plan to lobby government officials at local, state, and federal levels. The chief demand was for an ambitious program of public works that would provide jobs while repairing or building important public infrastructure. The UCL also called for a minimum daily wage of $4.50 and a moratorium on evictions for those who could not pay rent or taxes and advocated higher taxes on the wealthy. More ambitious was the demand that the state establish unemployment insurance as a basic right.

By October, city officials were paying attention, and even more so after the UCL began conducting a house to house canvas to count the number of jobless. The Vanguard cleverly reported the early results, comparing the numbers of unemployed with the number of registered voters in each neighborhood. "The percentage of the unemployed compared to the registered voting heads of families is as follows: Olympic Hts., 52%; Ballard, 34%; Georgetown, 75-80%; White Center, 83%."[2]

SELF HELP

As thousands joined the organization, UCL branches developed a second function as self-help cooperatives. Neighbors persuaded local businesses, farmers, and fishermen to donate food or other supplies. Farmers allowed UCLers to harvest fruit or vegetables that would not have made it to market. Other property owners allowed the cutting of firewood. Neighbors also went to work producing clothing and other objects for distribution throughout the growing UCL network. Branches became commissaries where members spent countless hours helping out and where those in need found food, clothes, firewood, etc. From the October 1931 issue of the Vanguard:

"The Rainier Valley branches have secured the loan of saws from City Light, trucks from the Eyres Transfer Co., free gas from the Stand Oil and putting on a 'Wood Week' on a truck turned over to them. They can keep all they can cut. West Seattle branches are planning to do the same."[3]

The UCL then approached the mayor and city relief authorities who reluctantly agreed to let the unemployed group handle the distribution of city funded food and commodities and supervise eligibility, a striking concession to the growing political influence of the UCL. King County authorities reached a similar agreement.

1932 ELECTION

Unemployed gather at city hall to celebrate the inaguration of mayor John Dore who had promised to support the UCL program. Within months he was breaking those promises (UW Libraries Special Collections #Lee236)

That influence would grow dramatically in March 1932 when the city held elections. With upwards of 20,000 members in Seattle (and thousands more in nearby towns and cities), the UCL was viewed by all candidates as the body that might determine outcomes. The incumbent mayor Robert Harkin hoped for support and had worked with the UCL on some matters but had done little to expand public works employment. On the other hand, challenger John Dore, an attorney, had supported UCL for months and now pledged himself to the organization's agenda. Dore won. So did two UCL endorsed candidates for city council.

Flush with victory, and now receiving national publicity, UCL leaders launched a statewide campaign. Expanding outside of Seattle and hoping to ally with farmers, they announced a new organization, United Producers of Washington, at a two-day conference in Tacoma. In addition, the UCL started a petition for a ballot measure to create a statewide unemployment insurance program.

YEAR TWO

As Terry Willis explains in her history of the UCL, even as the League celebrated its first anniversary in July 1932, things were becoming more complicated. The new mayor, John Dore, began to backtrack on promises. He carried through on his pledge to protect the big Hooverville from the police raids that had several times destroyed the burgeoning community. The shacktown would survive with city approval until 1941. He also followed up on his pledge to shake up the police department and drive out the grafters and crooked cops. But instead of expanding relief services and public works as he had pledged, Dore listened to business leaders who demanded fiscal restraint. UCL members cried foul as Dore announced cuts to the city budget and wage and workforce reductions for city employees.[4]

Meanwhile the campaign for unemployment insurance had stalled. The Governor, Roland Hartley, a rock-ribbed conservative from Everett, refused to call a special session of the legislature despite requests from most of the state's mayors as well as the Unemployed Citizens League. In response, the League called for a July 4th "Hunger March" to Olympia.

Planning for the march exposed another complication. The Communist Party, whose Unemployed Councils took the lead in organizing protests in many other states, had been overshadowed since the emergence of the UCL. The Unemployed Councils announced that they too were headed for Olympia. The ensuing rivalry undercut UCL plans for a big turnout and gave the state police an excuse to intervene. As marchers neared Olympia on July 3, they were met by a police barricade and were not allowed to enter the city. The governor then left town and on July 4 two groups of marchers, numbering perhaps 1,000 in all, were allowed to gather on the steps of an empty state capitol.

Rivalries and internal tensions were only beginning to affect the UCL in mid-1932. Reflecting a decade of sectarian struggles among radicals, Communists were initially banned from the UCL out of concern that they would introduce factionalism and try to take over the organization. They joined anyway and gained influence in some of the branches. Members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were also active, especially in the Capitol Hill branch. Sociologist Arthur Hillman recorded the tensions and changes that became apparent in the summer. Carl Brannin resigned the office of Executive Secretary of the League and the new leadership, dominated by "militants" drafted a new constitution. Meanwhile county authorities moved in and took control of the commissaries, claiming that the previous decision to allow UCL to control them had been a temporary measure and charging mismanagement and corruption in some branches. Hillman notes that the combination of internal discord and the diminished role in the distribution of food and commodities hurt the moral and membership numbers. With self-help functions undercut, people drifted away.[5]

1933 NEW DEAL

Democrats swept the election of November 1932, taking Congress and the Washington Governor's mansion as well as electing Franklin Roosevelt. Even before the New Deal Congress began passing relief and recovery laws in March 1933, Washington's legislature had set about reorganizing relief services, bringing them under state control. The Unemployed Citizen's League opposed the changes, denouncing the programs as underfunded and demeaning to the unemployed. The new programs also eliminated what was left of the organization's self-help and cooperative enterprises. Communist influence had also changed the organization, which now worked closely with the Communist led Unemployed Councils, focusing on militant protest and propaganda. A new Hunger March to Olympia and a three-day sit-in in the King County building were among the attention getting protests the two organizations staged in early 1933. But Communist influence grew at the expense of membership, and as the year continued more and more UCL branches ceased to function. In November, the Vanguard, which a year earlier had been renamed the Unemployed Citizen, published its final issue.

The Unemployed Citizens League made an enormous impact of Seattle and Washington State, providing a voice for the desperate and forcing authorities to take their needs seriously. With tens of thousands of members, the UCL was proportionally larger than the Unemployed Councils and other organizations that worked with the jobless in other states. And the message that UCL voters sent in the elections of 1932 rippled across the nation, helping jobless in other cities drag politicians into action. The political effects did not end as the UCL faded in 1933. Indeed, the organization laid the groundwork for a decade of radical activism. Soon, UCL veterans would be active in the revival of radical unionism in the Pacific Northwest. And they would turn the state's Democratic party sharply to the left. UCL attorney Marion Zioncheck was elected to Congress to represent Seattle in 1932, joining former socialist Homer T. Bone who that year won election to the US Senate. Other UCL veterans would later launch the Washington Commonwealth Federation which would elect radicals to the legislature and operate as a powerful leftwing caucus within the state's Democratic Party for next decade and half.

Copyright (c) 2020, James Gregory

Next: Strikes and Unions

[1] Terry R. Willis, Unemployed Citizens of Seattle 1900-1933: Hulet Wells, Seattle Labor, and the Struggle for Economic Security (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Washington, 1997), 196

[5] Arthur Hillman, “The Unemployed Citizens’ League of Seattle”(Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Washington, 1934).

We have detailed reports about the UCL, poverty activism, and its impact on Washington politics:

|

Self-Help Activists: The Seattle Branches of the Unemployed Citizens League by Summer Kelly

In the summer of 1931, a group of Seattle residents organized to establish self-help enterprises and demand that government officials create jobs and increase relief assistance to unemployed.

|

|

Interactive map of the Seattle Branches of the Unemployed Citizens League

This interactive map shows the Seattle locations of the the Unemployed Citizens League which established self-help commissaries and demanded jobs and relief services for the unemployed.

|

|

Vanguard and Unemployed Citizen, newspaper report by Erick Eigner

The Unemployed Citizen's League, a radical organization of unemployed men, put out two newspapers during the Depression Years.

|

|

On to Olympia! The History Behind the Hunger Marches of 1932-1933 by Ali Kamenz

In the summer of 1932 and again in March 1933, the Unemployed Citizens League joined with the communist Unemployed Councils to stage dramatic hunger marches from Seattle to Olympia. Despite police interference added to the pressure on state authorities to help the unemployed.

|

|

Organizing the Unemployed: The Early 1930s by Gordon Black

As elsewhere in the country, Washington State's Communist Party helped to organize the unemployed into active political and social formations. In Washington, the Unemployed Citizen's League and its newspaper, The Vanguard, gained the state Communists a broad appeal, and integrated the unemployed into the state's radical reform coalitions. |

|

Seattle’s “Hooverville”: The Failure of Effective Unemployment Relief in the Early 1930s by Magic Demirel

"Hoovervilles," shanty towns of unemployed men, sprung up all over the nation, named after President Hoover's insufficient relief during the crisis. Seattle's developed into a self-sufficient and organized town-within-a-town. |

|

A Tarpaper Carthage: Interpreting Hooverville, by Joey Smith

Seattle's Hooverville and its residents were portrayed as violent, exotic, and separate from the rest of Seattle, obscuring the social accomplishments and self-organization of shantytown residents.

|

|

"Nobody Paid any Attention": The Economic Marginalization of Seattle's Hooverville, by Dustin Neighly Seattle's decision to raze Hooverville in 1941 and expel its residents relied on a discourse of "otherness" that set Hooverville economically, socially, and geographically apart.

|

|