Click here to see more photographs of Hoovervilles and homeless encampments in Seattle and Tacoma.

"Hooverville" became a common term for shacktowns and homeless encampments during the Great Depression. There were dozens in the state of Washington, hundreds throughout the country, each testifying to the housing crisis that accompanied the employment crisis of the early 1930s.

"Hooverville" was a deliberately politicized label, emphasizing that President Herbert Hoover and the Republican Party were to be held responsible for the economic crisis and its miseries.

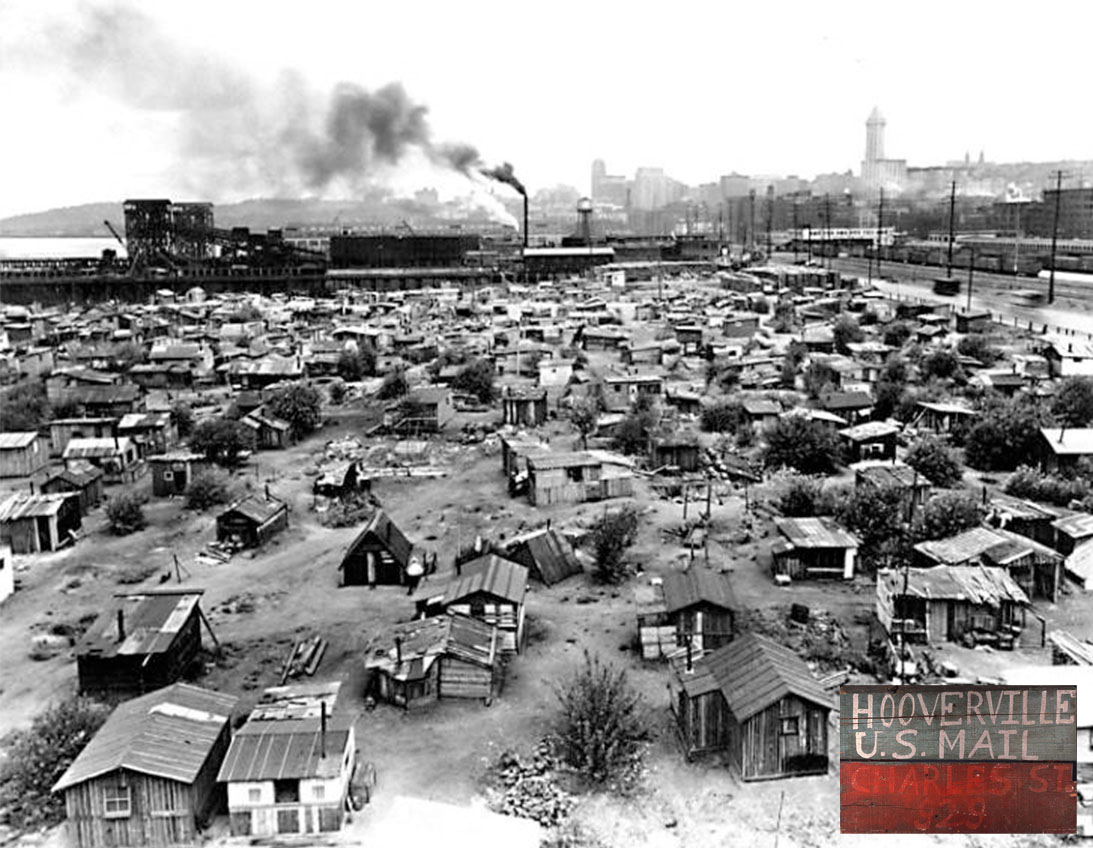

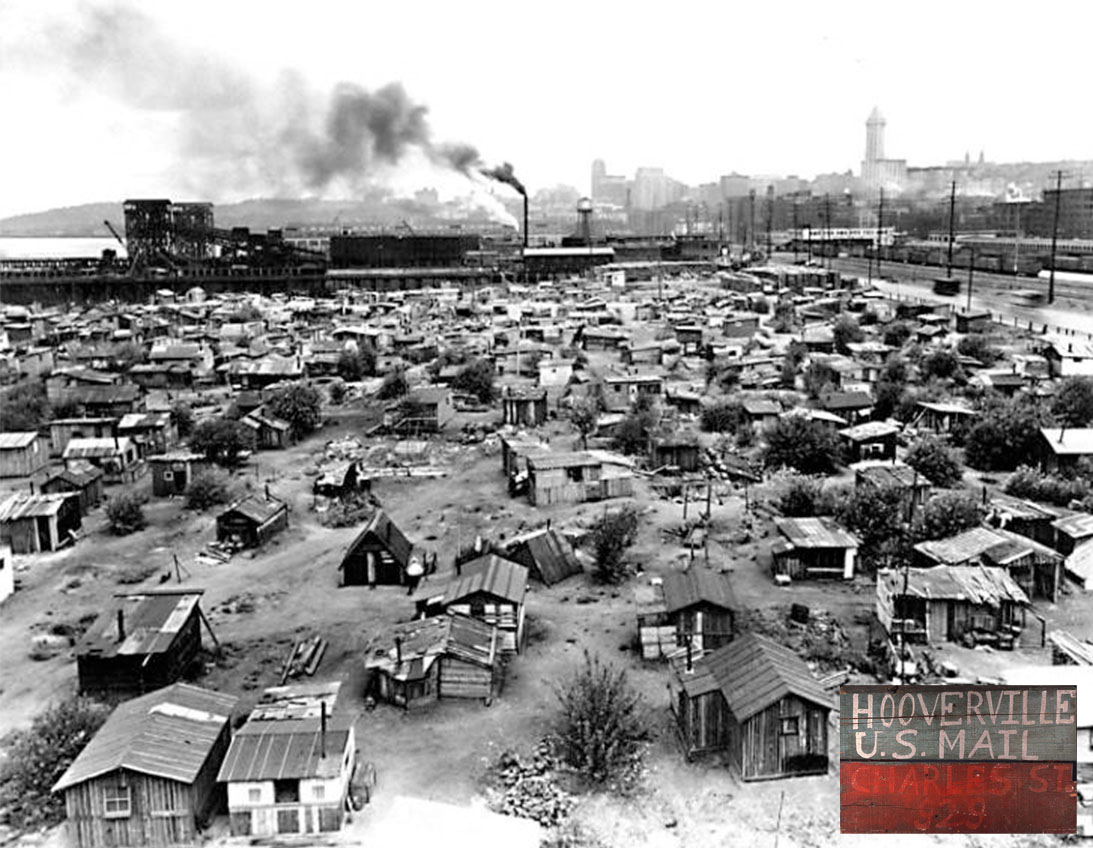

Seattle's main Hooverville was one of the largest, longest-lasting, and best documented in the nation. It stood for ten years, 1931 to 1941.

Covering nine acres of public land, it housed a population of up to 1,200, claimed its own community government including an unofficial mayor, and enjoyed the protection of leftwing groups and sympathetic public officials

until the land was needed for shipping facilities on the eve of World War II.

Seattle is fortunate to have the kind of detailed documentation of its Hooverville that other cities lack, and we have compiled these unique resources here. Included are photographs, city documents, a 1934 sociological survey of residents, a short memoir written by the former "mayor" of Hooverville, and more. We are grateful to the Seattle Municipal Archives, King County Archives, and the University of Washington Library Special Collections for permission to incorporate materials in their collections.

Homelessness

Homelessness followed quickly from joblessness once the economy began to crumble in the early 1930s. Homeowners lost their property when they could not pay mortgages or pay taxes. Renters fell behind and faced eviction. By 1932 millions of Americans were living outside the normal rent-paying housing market.

Many squeezed in with relatives. Unit densities soared in the early 1930s. Some squatted, either defying eviction and staying where they were, or finding shelter in one of the increasing number of vacant buildings.

And hundreds of thousands--no one knows how many--took to the streets, finding what shelter they could, under bridges, in culverts, or on vacant public land where they built crude shacks. Some cities allowed squatter encampments for a time, others did not.

Seattle's Housing Politics

Click to see google map of shack towns in Seattle area and more photos and descriptions.In Seattle shacks appeared in many locations in 1930 and 1931, but authorities usually destroyed them after neighbors complained. What became the city's main Hooverville started as a group of little huts on land next to Elliott Bay south of "skid road," as the Pioneer Square area was then called. This was Port of Seattle property that had been occupied by Skinner and Eddy shipyard during World War I. Today the nine acre site is used to unload container ships. It is just west of Qwest Field and the Alaska Viaduct.

Seattle police twice burned the early Hooverville, but each time residents rebuilt. When a new mayor took office in 1932, owing his election in part to support of the Unemployed Citizen's League, Seattle's Hooverville gained a measure of official tolerance that allowed it to survive and grow.

Hooverville's Population

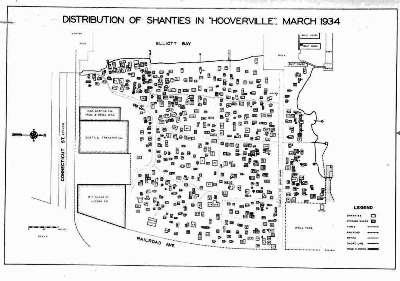

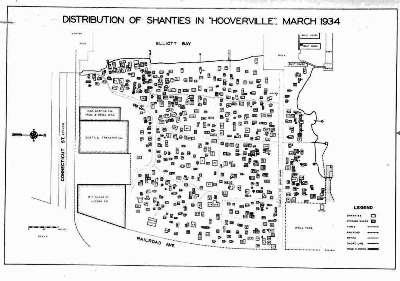

Donald Roy created this map of Seattle's Hooverville. Click the image to see a larger version of the map and here to read excerpts from Roy's sociological survey.By 1934 nearly 500 self-built one-room domiciles were "scattered over the terrain in insane disorder," according to Donald Roy, a sociology graduate student who studied the community. He counted 639 residents in March of that year, all but seven of them men. Most were unemployed laborers and timber workers, few of whom had held any jobs in the previous two years. It was a highly diverse population. Most were white with the majority of them foreign-born, especially Scandinavians. Nonwhites comprised 29% of the colony's population, including 120 Filipinos, 29 African Americas, 25 Mexicans, 4 Native Americans, 4 South Americans, and 2 Japanese. Roy found the relaxed social atmosphere remarkable, describing "an ethnic rainbow" where men of many colors intermingled "in shabby comraderie."[1]

The city imposed modest building and sanitation rules, required that women and children not live in the Hooverville, and expected the residents to keep order. This was handled by an elected Vigilance Committee-- consisting of two whites, two blacks, and two Filipinos-- led by a white Texas native and former lumberjack named Jesse Jackson, who came to be known as the unofficial "Mayor" of Hooverville. In 1938, Jackson wrote a short, vivid description of the community that we reproduce here. He explained that the population was fluid, as men sold their shacks to newcomers and moved on, and at its maximum during the winter months when it reached as hight as 1,200. He was proud of the self-built community, saying "Hooverville is the abode of the forgotten man." [2]

Other Hoovervilles also developed: one on the side of Beacon Hill where today I-5 passes; one in the Interbay area next to where the city used to dump its garbage; and two others along 6th Avenue in South Seattle. In late 1935, the city Health Department estimated that 4,000 to 5,000 people were living in the various shacktowns.[3]

The city tolerated Hoovervilles until the eve of World War II. Early in 1941, the Seattle Health Department established a Shack Elimination Committee to identify unauthorized housing clusters and plan their removal. A survey located 1687 shacks in five substantial colonies and many smaller ones. In April, residents of the main Hooverville were given notice to leave by May 1. Police officers doused the little structures with kerosene and lit them as spectators watched. Seattle's Hooverville had lasted a full decade.[4]

Tacoma's "Hollywood-on-the-Tideflats" was burned by city officials in May 1942, but was soon reoccupied and rebuilt. Courtesy Tacoma Public Library.

Shanty towns also appeared in or near other cities. Tacoma hosted a large encampment near the city garbage dump that residents called "Hollywood-on-the-Tideflats." By the end of the decade it covered a six block area and, like Seattle's Hooverville, included a large number of little houses that residents had built out of scrap materials and steadily improved over the years. City officials alternately tolerated and tried to eradicate the shack town. In May 1942, shortly after Seattle destroyed its Hooverville, the Tacoma Fire Department burned fifty of the "Hollywood" shacks. But residents rebuilt and the site remained occupied all the way through World War II.

Copyright (c) 2009, James Gregory

Next: Unemployed Citizens League and Poverty Activism

Here is more on Hoovervilles:

Research Reports |

|

Seattle’s “Hooverville”: The Failure of Effective Unemployment Relief in the Early 1930s by Magic Demirel

"Hoovervilles," shanty towns of unemployed men, sprung up all over the nation, named after President Hoover's insufficient relief during the crisis. Seattle's developed into a self-sufficient and organized town-within-a-town.

|

|

A Tarpaper Carthage: Interpreting Hooverville, by Joey Smith

Seattle's Hooverville and its residents were portrayed as violent, exotic, and separate from the rest of Seattle, obscuring the social accomplishments and self-organization of shantytown residents.

|

|

"Nobody Paid any Attention": The Economic Marginalization of Seattle's Hooverville, by Dustin Neighly Seattle's decision to raze Hooverville in 1941 and expel its residents relied on a discourse of "otherness" that set Hooverville economically, socially, and geographically apart.

|

|

Self-Help Activists: The Seattle Branches of the Unemployed Citizens League by Summer Kelly

In the summer of 1931 a group of Seattle residents organized to establish self-help enterprises and demand that government officials create jobs and increase relief assistance to unemployed.

|

|

Organizing the Unemployed: The Early 1930s by Gordon Black

As elsewhere in the country, Washington State's Communist Party helped to organize the unemployed into active political and social formations. In Washington, the Unemployed Citizen's League and its newspaper, The Vanguard, gained the state Communists a broad appeal, and integrated the unemployed into the state's radical reform coalitions.

|

| |

|

Primary Source Documents |

|

The Story of Seattle's Hooverville by Jesse Jackson, "Mayor" of Hooverville |

|

Hooverville: A Study of a Community of Homeless Men in Seattle by Donald Francis Roy

Roy lived in the Hooverville in spring 1934 while conducting this survey which became his 1935 MA thesis. He offers fascinating observations about social mores and culture of the community, including the easy racial relations and tolerance of homosexuality.

|

|

Seattle Municipal Archives Documents

Petition for community bath houses in Hooverville (May 15, 1935)

Response from Health Department (May 23, 1935)

Excerpt from Health Department Annual Report (1935)

Request for removal of Interbay shacks (April 24, 1937)

Protest against Hooverville evictions (October 10, 1938)

Letter from Housing Authority to City Council (March 4, 1941)

Report of Shack Elimination Committee (April 14, 1941)

Exhibt A: Map of Number and Distribution of Shacks (March 5, 1941)

Exhibit B: Location and Number of Shacks (March 5, 1941)

Exhibit C: Physical Conditions and Occupancy of Shacks (March 5, 1941)

Excerpt from "The Story of Hooverville, In Seattle" by Jesse Jackson, Mayor of Hooverville (1935)

Excerpt from "Hooverville: A Study of a Community of Homeless Men in Seattle" by Donald Francis Roy (1935)

Excerpt from "Seattle's Hooverville" by Leslie D. Erb (1935)

|

Notes

[1] Donald Francis Roy, "Hooverville: A Study of a Community of Homeless Men in Seattle," (M.A. Thesis, University of Washington, 1935), pp.42-45

[2] Jesse Jackson, "The Story of Seattle's Hooverville," in Calvin F. Schmid, Social Trends in Seattle (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1944), 286-93.

[3] Report of the Sanitation Divison December 31, 1935 as quoted in Excerpt from the Health Department Annual Report 1935, Seattle Municipal Archives: http://www.seattle.gov/CityArchives/Exhibits/Hoover/1935ar.htm (accessed December 29, 2009)

[4] Report of Shack Elimination Committee (April 14, 1941), Seattle Municipal Archives (accessed December 29, 2009)