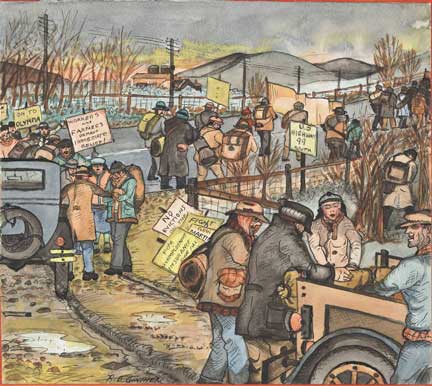

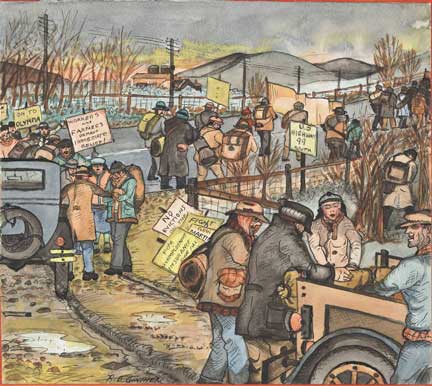

The unemployed organized a "hunger march" on the state capitol of Olympia in March, 1933, pictured here by Depression-era artist Ronald Debs Ginther. 'Near Tacoma, Washington. March 1933. The Great Depression. King Co., and Seattle Contingent, Washington State Hunger March on Olympia.' 1933. (Property of Washington State Historical Society, all rights reserved.)

The stock market crash of October 1929 signaled the start of what became known as the Great Depression. Falling stock values helped undermine consumer confidence and business investment, leading to a sharp economic decline that spread from the United States to other countries and continued for nearly three and a half years. Not until the spring of 1933 did the American economy begin to recover.

Washington experienced the crisis in ways that were somewhat different than other states. The economy had been highly dependent on extractive industries, especially forest products. A government report explained that the economy of the region "largely resembles that of a colonial possession, exporting raw and semifinished materials" while importing "most of the common manufactured articles."[1] Forest products, agriculture, fishing, and mining accounted for most of the state's exports and many of its jobs on the eve of the Depression, but the state's cities, where most of the population lived, also produced jobs based on trade, commerce, small manufacturing, and professional services.

Far from Wall Street, Washington residents were slow to react to the events of October 1929. As the stock market tumbled, the Seattle Times reassured readers in a big headline that there would be "No Depression."[2] Indeed, job losses were modest for the first year. But the optimism faded toward the end of 1930 as banks began to fail, stores closed, and unemployment surged.

Policy makers then managed to make things worse. In the nation's capital, President Herbert Hoover presided over a series of decisions that accelerated and globalized the economic decline. In Olympia, the state legislature, meeting early in 1931, passed a bill to help the unemployed and stimulate the economy with an ambitious program of public works projects. They also passed a state income tax to take some of the burden off property taxes. Governor Roland Hartley vetoed both measures and preceded to slash spending, as did many of the cities and counties. Bank failures, business failures, and job losses accelerated.

Unemployment rates exceeded the national average but were kept lower than in states like Michigan and Ohio where so many jobs depended on one or two massive industries. Hardest hit in Washington, as in many states, was the building and construction industry where payrolls by late 1932 were about 10 percent of what they had been four years earlier. Logging and sawmills saw employment drop by at least 50 percent and payrolls still further. But employment in food processing, the transportation sector, utilities, and road construction held up even at the lowest point of the Depression, and a few smaller industries, notably pulp and paper mills, actually added jobs and expanded payrolls in 1932 and 1933. Overall, it is estimated that total income payments in the state fell by 45 percent by 1933 which was similar to the average decline for the nation as a whole. But at least one third of Washington's labor force was unemployed in early 1933, with still higher rates in Seattle and other cities where the jobless congregated. These rates were higher than the national average, which is thought to have peaked at 25 percent.[3]

Poverty and homelessness

Hooverville in the Interbay neighborhood of Seattle, 1938. Courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry Photo Archives. Click to see more Seattle Hoovervilles.

Since the government provided no unemployment insurance, lost jobs quickly translated into lost homes and extreme poverty. In 1931, tent camps and shack towns began to appear. One large encampment that residents called "Hooverville" --in honor of the President whom they blamed for the Depression--grew in the mudflats south of downtown Seattle near Elliott Bay. City authorities ordered the site burned but it was quickly rebuilt, becoming in time a nearly all-male community of more than one thousand residents. Tolerated by authorities, it remained occupied until torn down by the city in 1941.

Until 1933 when federal assistance began, it was up to local authorities to assist unemployed residents. Counties and cities did what they could, establishing work programs more often than direct relief, but declining tax revenues made it hard to do very much. Even as the need to help soared in 1931 and 1932, Seattle, like many other cities, actually cut welfare budgets as businesses closed and homeowners defaulted on taxes. Churches and charities also helped as more fortunate residents often gave generously to feed and clothe the poor.[3a]

Founded in mid 1931, the Unemployed Citizen's League demanded more funds and different kinds of programs for the unemployed and forced city officials to leave Hooverville alone. With clubs in most neighborhoods of Seattle and Tacoma and several other cities, the UCL advocated self-help production, setting up cooperatives to exchange products and services. Farmers donated food in exchange for labor; carpenters, dentists, and seamstresses exchanged one kind of skill for another. In Seattle, UCL was so popular and powerful that the city's relief office used it to distribute public resources to the poor. For two years, as the economy went from bad to worse, the UCL helped some of the unemployed maintain themselves.

Recovery, 1933-1937

When Franklin Roosevelt assumed office in March 1933, the economy was nearly stalled. Congress quickly passed a sequence of emergency measures to rescue the banking system, send emergency aid to the states, and begin to re-employ the millions who were out of work. Federal funds to Washington State were funneled through the Washington Emergency Relief Administration, a state agency that dispersed some money directly to the poor in the form of cash grants while also launching dozens of public works projects that created new jobs. Soon there would be more jobs coordinated with federal agencies. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) would employ thousands of young men in the forests and national parks of Washington State. The Civil Works Adminstration set up small public works jobs, while the Public Works Administration planned huge new infrastructure projects that included Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams on the Columbia River. In 1935 many of the jobs and construction programs were consolidated under the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

With federal help, the state economy began a dramatic recovery, faster than many other states. By 1937, income payments in Washington (our best measure of economic activity) had returned to 93 percent of the 1929 level. Nationally, the level was 88 percent. Employment in the region's key industry, forest products, keyed the recovery. In 1937, there were almost as many workers employed in the woods, sawmills, paper mills, furniture, and wood products factories as in 1929, although wages remained well below normal. Other parts of the economy had rebounded, though not so dramatically, but the recovery was soon thwarted when the over-confident Roosevelt administration cut spending in an effort to balance the federal budget. The national economy and state economies now descended into a second depression, which economists euphemistically labeled a "recession," coining the term that ever since has been used to describe economic downturns.[4]

Renewed federal spending pulled both the state and nation out of the 1937 recession. When census takers collected information about employment in March 1940, the Washington jobless rate stood at 9.9 percent with another 5.3 percent working on WPA and CCC projects. This was close to the national average that month.[5]

But the days of unemployment were soon to end. With war looming, the federal government needed planes and ships and Washington would build both. The new electricity generated by Bonneville and other Columbia River dams would power the shipyards of Vancouver and the Puget Sound. Cheap energy made Seattle into one of the nation's aircraft capitals, as new electricity-hungry aluminum plants provided what Boeing needed to build America's bomber squadrons.

By the end of 1942, 150,000 workers labored around the clock in the state's shipyards and aircraft factories. Not only was the Depression a memory, the state was now looking at its new economy, based more on planes than on trees, and firmly rooted in new industries that the federal infrastructure investments of the 1930s had made possible.

Copyright (c) 2009, James Gregory

Next: Hoovervilles and Homelessness

Click on the links below to read illustrated research reports on economics and poverty during Washington State's Great Depression:

|

Why Washington State Doesn't Have an Income Tax: The 1930s Campaign for Tax Reform and the Origins of Washington's Tax System by Nathan Riding

Washington's tax system proved inadequate to the growing needs of Washington State's infrastructure. The 1930s saw a broad-based movement for an income tax in the state, led by rural farmers in the Washington State Grange. Stiff political opposition prevented the adoption of an income tax, which it still does not have today and which constrains public spending and social services.

|

|

|

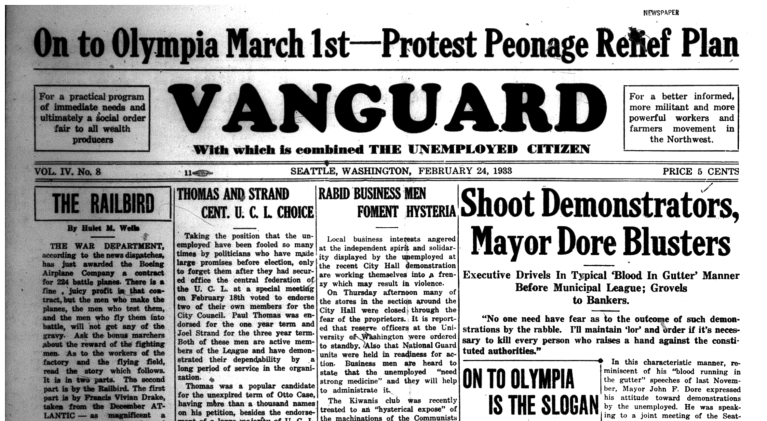

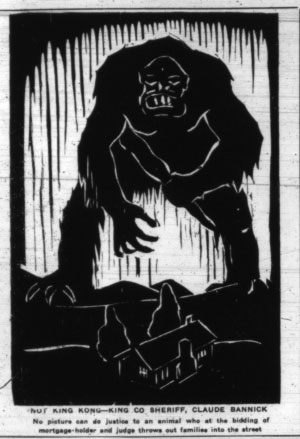

On to Olympia! The History Behind the Hunger Marches of 1932-1933, by Ali Kamenz

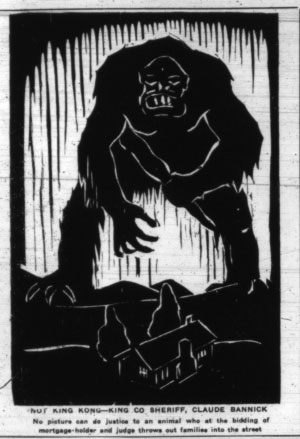

During the early 1930's, the poor and unemployed participated in a series of marches on the capitol in Olympia to demand food, work and housing. Once there, they encountered indifference, hostility, and violence from elected officials, local law enforcement and vigilantes. The Vanguard, a Seattle-based publication affiliated with the Labor College, and the Unemployed Citizens' League, played key roles in march planning and organization.

|

|

The Banking Crisis of 1933: Seattle's Survival during the Great Depression Bank Closures, by Drew Powers

The nationwide banking crisis of 1933, brought on by corruption, customer loan defaults, and an unstable banking system brought first state-wide and then nation-wide bank closures in 1933. Seattleites developed different strategies for surviving without cash, while Roosevelt and Congress stabilized American capitalism and preserved public faith in American finance.

|

|

Seattle’s “Hooverville”: The Failure of Effective Unemployment Relief in the Early 1930s by Magic Demirel

"Hoovervilles," shanty towns of unemployed men, sprung up all over the nation, named after President Hoover's insufficient relief during the crisis. Seattle's developed into a self-sufficient and organized town-within-a-town.

|

|

Self-Help Activists: The Seattle Branches of the Unemployed Citizens League by Summer Kelly

In the summer of 1931 a group of Seattle residents organized to establish self-help enterprises and demand that government officials create jobs and increase relief assistance to unemployed.

|

|

The Unemployed Councils of the Communist Party in Washington State, 1930-1935 by Marc Horan-Spatz

Following the stock market crash of 1929, the Communist Party began to organize unemployed workers into Unemployed Councils. These bodies both provided aid to the needy and served as a tool to build mass support for the Party and its political program. In Washington State, the Councils were in direct competition with the Socialist-led Unemployed Citizens League, which led to tensions between the two organizations.

|

|

Organizing the Unemployed: The Early 1930s by Gordon Black

As elsewhere in the country, Washington State's Communist Party helped to organize the unemployed into active political and social formations. In Washington, the Unemployed Citizen's League and its newspaper, The Vanguard, gained the state Communists a broad appeal, and integrated the unemployed into the state's radical reform coalitions.

|

[1] Pacific Northwest Regional Planning Commission, Migration and Development of Economic Opportunity in the Pacific Northwest (Portland, 1939), 26.

[2] Seattle Daily Times, October 27, 1929, p.1

[3] Pacific Northwest Regional Planning Commission, Migration and the Development of Economic Opportunity in the Pacific Northwest (Portland: National Resources Planning Board, Region 9, August 1939), p.95 and p. 154, Table 2. Also see data assembled by John Adrian Rademaker, "The Measurement of Occupational Employment and Earnings in the State of Washington" (MA Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, 1935).

[3a] William H. Mullins, The Depression and the Urban West 1929-1933: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland (Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1991), 95-105.

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940. Population. Vol 111. Labor Force. Part 5. Table 1: Employment Status of the Population.