The Depression and the 1930s brought many changes to the University of Washington, from budget cuts to labor disputes and New Deal infrastructure changes. In this page from the 1934 "Tyee" yearbook, UW students commemorate larger political changes next to a picture of campus. Click image to enlarge. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Digital Collections)

Universities and colleges should serve as shock-absorbers in times of economic crisis. When other opportunities disappear, young people--and not so young people--look to educational institutions for intellectual growth and new job skills. But Washington’s political leaders were not smart in the early 1930s. Instead of expanding educational opportunities, they slashed budgets and cut enrollments.

The Great Depression led to a great economic crisis for individual students as well as the University of Washington, which fostered administrative as well as social changes to University structure and student life. Wrestling with budget cuts, tuition issues, and labor conflicts, the University developed a new relationship with both students and faculty, abandoning some of its earlier elitist postures in the face of public demands for enrollment increases, student demands for free speech, and faculty demands for academic freedom and a decision making role in institutional governance.

The Crisis

The University of Washington had grown dramatically in the 1920s, from an enrollment of less than 3,000 at the close of World War I, to over 8,500 for the 1930-1931 school year. There had been struggles with the governor and legislature over funding and battles with students over tuition, especially after the UW imposed a fifty percent increase to make up a deficit. When Roland Hartley became governor in 1925, the University’s problems doubled. The conservative Republican fired longtime UW President Henry Suzzallo, stacked the Board of Regents with his friends, and vetoed salary and funding increases. Thus even before the Depression, the UW was operating under tight budgets and an unsympathetic governor.[1]

The economic collapse of the early 1930s turned quickly into a crisis for the university and for its students and faculty. The Depression made it impossible for some students to continue their education. Some quit school to help their families, others because they could no longer pay tuition and expenses, particularly as it became more and more difficult to find the kinds of part-time jobs that working-class students had relied upon.

The student newspaper, The Daily, ran a story in January 1930 about Dan Marsh, a student forced to drop out of college after a family member died. The paper reported that he had to resort to begging, stealing, and bread lines to survive.[2] Others were luckier: student Alda Martell was planning on leaving school in 1930, but a $100 scholarship made it possible for her to finish her studies.[3] How many left is not clear, but student enrollment dropped eight percent, from 8,583 to 7,915 between fall 1930 and fall 1931 and another eight percent to 7,193 in the 1932-33 academic year.[4] Meanwhile the university saw its budget cut dramatically in 1931 and then again in 1932. Washington was struggling, as were all states, with declining tax revenues. Property taxes were the sole substantial source of state funds in the early 1930s, but homes and farms were being lost to foreclosure and many remaining owners were desperate for tax relief. The legislature, meeting in early 1931, came up with a solution, passing a bill that would have established a tax on personal and corporate income. But Governor Hartley vetoed it. A pair of ballot measures the following year put the issue to voters, one creating an income tax, the other providing property tax relief. Both passed overwhelmingly. But then in a surprising decision, the state Supreme Court ruled that the income tax was unconstitutional. Going into 1933, the state faced an even bigger budget crisis than before since property taxes had been cut without anything to take their place.[5]

That year Clarence Martin replaced Hartley as governor. The moderate Democrat had run on a promise to lower tuition and ease admission requirements to make higher education accessible to more Washingtonians. At the same time, he cut deeply into the University budget. The Regents agreed to both the enrollment increase (adding 1,000 new students) and the tuition cut (but then raised other student fees). 1933 saw the student population increase from 7,193 to 8,469.[6]

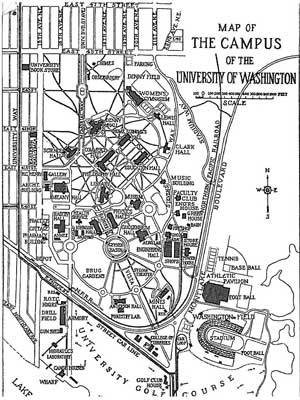

This 1929 map shows a campus framed by a street car line on the south and west and railroad tracks to the east. Most of the buildings from that era today have different names and functions. Click to enlarge.

To handle the budget cut, the Regents cut salaries for the second time. In 1933 faculty and staff made 30-40 percent less than they had a few years earlier, and some lost their jobs. The teaching staff was at least 10 percent smaller that year, with those remaining asked to do more work for less pay. Teaching loads and class sizes shot up. Students faced classes that were 70% larger than at peer institutions, and staged protests demanded that Governor Martin keep his promises. The student paper, The Daily, surveyed campus and declared that at least fifty-nine new faculty were needed to handle the needs of student population.[7]

It eventually took the combined protest of students, faculty, and regents to convince the Governor that he needed to fund the hiring of new instructors and mitigate the faculty pay cut. In December 1933, the Regents announced plans to hire one hundred new instructors and restore half of the salary cut. The next year there was further improvement and by 1935-36, funding had returned almost to the level of 1930-31. This became possible because the legislature has overhauled the state tax structure, allowing education to be funded from sales and business taxes, increasing, somewhat, state revenue for higher education. But the dollars were not exactly keeping up with the students. Enrollment surged passed 9,200 as classes began in October 1935 and stayed above 9,000 for the remainder of the decade.[8]

Infrastructure changes

A ball field at the University of Washington, one of many public works projects undertaken during the Great Depression that remade the University campus. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Digital Collections) Click picture to see more Civilian Works Administration photographs.

Public works spending benefited the campus even as the University struggled to find money for its operating budget and its educational mission. At the end of 1935, President Sieg proclaimed that "half as much money has been spent on new buildings in the past two years as was spent in the previous 70 years of the University's history."[9] Federal and state funds paid for a new domitory, an infirmary (now Hall Health), Chemistry Building (now Bagley), Law School (now Gowen) and Smith Hall. Federal dollars built new ball fields and athletic facilities, a new campus power plant, and helped UW add a wing to Suzzallo Library. Students who today fill the quad area in upper campus during the interval between classes walk on brick pathways laid down in 1934 by workers employed by the Civil Works Administration. Most notable of the new projects was the Washington Park Arboretum, owned by the City of Seattle, managed by the University of Washington, and funded largely by the WPA which provided jobs to over 500 men.

Other structures were also changed. After years of leadership turmoil, the Regents, under the watchful eye of Governor Martin, named Lee Paul Sieg as University President in 1934. Sieg implemented a number of changes in curriculum and governance. He reorganized academic units, unifying the arts and sciences into a single college and instituting a comprehensive general and compensatory education to overcome unevenness in the preparation of incoming high school graduates.

Student Life during the Depression

Higher education in the 1920s had mostly been beyond the reach of working-class young people. Even public institutions like the UW catered to students whose families had the financial means to support them. Student culture reflected this middle- and upper-class composition. Fraternities and sororities set the tone and dominated student affairs. Athletics was king. The student newspaper reported mostly on the activities of Greeks and endless numbers of student clubs.

The Great Depression in time altered the composition and outlook of the student body. As admissions rebounded, some of the new students came from humbler circumstances, and many needed to support themselves as they pursued their studies. Government programs helped. In 1935, the federal government established the National Youth Administration, a relief agency for unemployed young adults and students. Around the state, students were paid to work in campus libraries and cafeterias, conduct research, and maintain buildings. By 1937, The Daily reported that one in every ten students at UW held an NYA job.[10]

Students eating lunch on the lawn during the Campus Day celebration, 1933. Click image to enlarge. (Courtesy of University of Washington Library, Special Collections)

The political tone of student life also changed. Colleges before the 1930s usually bred conservatism. A nationwide attempt to survey students on the eve of the 1932 election, suggested majority support for Herbert Hoover instead of Franklin Roosevelt. The UW Daily reported similar results on the Seattle campus, where 60% of those responding to the unscientific poll said they supported Hoover, against 29% for Roosevelt, and 12% for the Socialist candidate Norman Thomas.[11]

In the years that followed, liberal and radical voices became more evident on campus. The 1930s would see nothing like the widespread student radicalism of the 1960s and much of student life, at least as it was reflected in the UW Daily, appeared remarkably unchanged. Nothing interfered with the thriving athletics program, and social events for men and women still dominated the pages of the student newspaper throughout the decade. But visible too was an expanding involvement with broader community concerns and more political forms of activism.

In 1931, a group of UW students formed a Student Cooperative Association, which may have had links to the Unemployed Citizens Council, and pledged to provide material support for students and the community. Later in the decade students ran community fundraisers and clothing campaigns for the unemployed. Other organizations supported unions and demanded social reforms. Students protested the overcrowding of classrooms and the dismissal of popular professors. In addition, the campus after 1933 saw the emergence of a strong student peace movement.

Unions and Academic Labor

Faculty outlooks and politics were also transformed. The funding difficulties of the 1920s and early 1930s had left the University with an underpaid faculty and had led to an unfortunate experiment with contingent faculty, paid less than professors, denied a chance at job security or promotion, and indeed not always recognized as faculty members. Lecturers, Associates, and Teaching Assistants–often female, often graduate students or former graduate students, and sometimes high school teachers hired without advanced degrees--found themselves unqualified to advance to professor status and stuck in a marginal, tenuous, and voiceless space within the University. By 1925, 25% of courses were being taught by un-tenured, low-paid sub-faculty, and the percentage increased in the early 1930s[12]

The faculty had developed an organization to represent their interests and negotiate with the administration. The Instructor’s Association (IA), formed in 1919, was the forerunner of today’s Faculty Senate. It enjoyed some influence and at times was able to win salary increases for regular faculty and also an expanded faculty role in university governance. The IA also declared that it was concerned about the fate of Lecturers and Associates but proved much less effective on that score. Even when regular faculty gained salary boosts, the administration refused to share the increase with the so-called “sub-faculty.” This led to a split between lower and higher-level faculty, and the IA’s attempts, during the 1930s, to seek a greater administrative role within the University rather than to protest from without created an opportunity for the emergence of more radical faculty organization.[13]

In 1935, radical and Communist faculty members established Local 401 of the American Federation of Teachers, nicknamed the Teacher’s Union, seeking to address the grievances and voicelessness of sub-faculty on campus and also gain a platform for the expression of more radical and expansive political ideas. University President Sieg refused to negotiate with the Teacher’s Union, preferring to work with the more moderate Instructor’s Association, and the Teacher’s Union’s radical politics made the organization susceptible to anti-Communist repression in the 1940s. However, despite its short life span, the Teacher’s Union provided an amount of redress for sub-faculty, won small gains, and served as a focal point on campus for more radical visions of society and labor.

Art professor Lea Miller was fired from the University of Washington in 1938 under the "anti-nepotism" policy which favored male workers and denied jobs to married women. Miller made her case a flashpoint of national protest. This image and article are from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 4, 1938. Click image to enlarge.

Women faculty faced an additional battle. In 1936, the University began firing its small cohort of married female staff as part of the state’s employment policy that favored male-headed households and frowned on married women’s “second incomes” in a time of high unemployment. Affected were art professor Lea Puymbroeck Miller, Seattle Repertory Playhouse director Florence Bean James, and economist and political scientist Teresa McMahon. While Miller made her own defense into a national debate on women in the workforce, long-time faculty member McMahon, accustomed to combating the sex-segregation policies in her own field, struggled privately with the administration.[14]

The proliferation of labor struggles and the newly won right to organize spread to non-faculty employees of the University as well. In 1937, cooks, maids, and so-called “houseboys” in University housing and area restaurants began a union organizing drive as well, hoping to affiliate with the larger Cooks and Waiters’ Union and take advantage of collective bargaining agreements. Houseboys generally received only meals and a room for their daily work, and sought to organize for an hourly wage.[15]

The unions were short-lived, however much they reset the tone and agendas of campus life. But for regular faculty the activism of the 1930s brought lasting changes. After years of negotiating with the Instructor’s Association and worried about the possibility that the Teacher’s Union would capture the loyalty of more faculty members, President Sieg and the Board of Regents agreed to fundamental changes in the relationship between regular faculty and the administration. Faculty would gain an official role in university governance. In 1938, the Instructors Association became the Faculty Senate, an elected body that would officially share in University governance. Sieg also agreed to an administrative code that established faculty authority over the curriculum and the educational polities of the University. Two years later, regular faculty won an additional victory when a standardized procedure for awarding tenure and general principles safeguarding academic freedom became part of the code.[16]

War looms

Campus struggles over labor, University structure, and faculty rights took place in the context of war in Europe, the rise of Hitler, and the build-up to American intervention in World War II. The coming of war produced campus protest on both sides of the political spectrum, and new ways in which the campus worked with the broader community.

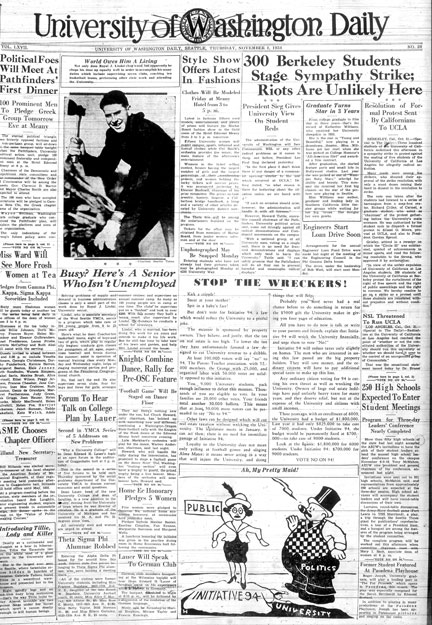

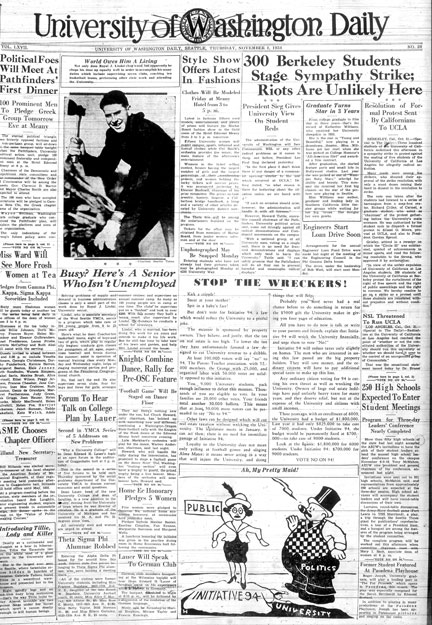

The front page of the UW Daily provides a glimpse of campus life and politics on November 1, 1934. The lead article reassures readers that radicals and communists are not likely to cause trouble. Another introduces the Pathfinders, a conservative student group. A cartoon takes aim at a ballot measure that threatens UW funding, while other articles profile a hard-working senior and an upcoming fashion show. Click to enlarge.

After 1933, the rise of fascism in Europe, combined with fears of Japanese militarism and skepticism of rising military costs at home prompted the formation of the first national American student antiwar movement, centering around the threat of war and the inhumanity caused by the Depression. With its roots in the long traditions of left-wing American radicalism and communism, the student movement of the 1930s organized the first national student strikes. At the UW, the “Thursday Noon Club” formed to bring political speakers to campus, and pacifist students protested for the right of free speech to air their political antiwar views on campus, a practiced denied by President Sieg. In 1935, a campus poll even indicated that students might join a nationwide strike against war and fascism.[17]

At the same time that radical students were organizing, conservative students were building their own movements. At the invitation of University President Sieg, the “Pathfinders” organization brought together fraternity leaders, the editor of The Daily, and student government officials to champion American power and, sometimes, disrupt radical students’ protests.

With the increasing likelihood of American involvement in World War II and the national economic recovery with wartime production, the University devoted all its effort to war production. Home economics classes learned to can food to be sent overseas, the ROTC and Navy established units on campus and stationed new recruits in the dormitories, University scientists researched chemical warfare, the oceanography department conducted secret investigations for the military, engineers helped design new ships and B-29 bombers, and in 1943, the University created an applied physics laboratory as a semi-permanent defense department contract program.[18] Following World War II, postwar economic prosperity and the federal funds of the GI Bill allowed for the expansion and growth of the University that would temporarily paper over the budget and labor problems of the 1920s and 1930s.

Copyright (c) 2009, Jessie Kindig

Next: Everyday Life during the Depression

Click on the links below to read illustrated research reports about labor struggles, student life, and public works programs at the University of Washington during the Depression:

|

Communism, Anti-Communism, and Faculty Unionization: The American Federation of Teachers' Union at the University of Washington, 1935-1948, by Andrew Knudsen

The founding of an AFT-affiliated faculty union at the University of Washington allowed faculty job security and redress during the economic crisis. Yet the radical and sometimes Communist politics of its members made the union susceptible to federal anti-Communist repression by the 1940s.

|

|

Challenging Gender Stereotypes during the Depression: Female Students at the University of Washington, by Nicolette Flannery

Female students in the 1930s challenged accepted ideas of women's education, participation in college athletics, and domestic and social responsibilities.

|

|

Depression-era Huskies: Student Life and School Spirit during the Great Depression, by Annie Walsh

Student life during the Depression was changed by budget cuts and tuition rates, yet there was a thriving athletic, social, and cultural atmosphere on campus.

|

|

Working Women at UW series: Depression-era labor policies did not allow married women to hold jobs, favoring a husband's work. Prof. Lea Miller at the UW was fired, and sparked a national protest over the policy.

• Part 1:Lea Miller's Protest: Married Women's Jobs at the University of Washington, by Claire Palay

• Part 2: Married Women's Right to Work: "Anti-Nepotism" Policies at the University of Washington during the Depression, by Katharine Edwards

|

|

The Spanish Civil War and the Pacific Northwest, by Joe McArdle

Nearly seventy men volunteered to fight with the Abraham Lincoln Brigades during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1937. on the side of the democratically elected Spanish government against Franco's fascists. This paper surveys the political attitudes and backgrounds of those volunteers, with an emphasis on University of Washington students who enlisted.

|

Notes:

[1] Charles M. Gates, The First Century at the University of Washington, 1861–1961 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1961), 169; Richard C. Berner, Seattle, 1921–1940: From Boom to Bust, (Seattle: Charles Press, 1992), 242.

[2] “When the Skidroad turned Collegiate.” University of Washington Daily, January 22-23, 1930.

[3] “$100 Scholarship won by University Woman.” University of Washington Daily, January 27, 1930.

[4] UW Catalog, 1930-34, as reported in Annie Walsh, “Tough Times, Tough Students,” Great Depression in Washington State Project

[5] Phil Roberts, A Penny for the Governor, A Dollar for Uncle Sam: Income Taxation in Washington (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 73-85

[6] University of Washington Catalog, 1932-1934 as reported in Walsh, “Tough Times, Tough Students.”

[7] Gates, The First Century, 180.

[8] "Fall Registration Breaks All Records," University of Washington Daily, October 1, 1935; Berner, Seattle, 1921–1940, 236; Gates, The First Century,180.

[9] "3 1/2 Millions to be Spent in 1936," University of Washington Daily, December 10, 1935.

[10] “Poor Working Man is a Collegian Now: One student in every 10 on NYA,” University of Washington Daily, February 10, 1937.

[11] “Poll Of University Will Be Evaluated in Elections Today,” UW Daily, November 8, 1932, p.1.

[12] Berner, Seattle. 1921-1940, 238-239; Gates, The First Century, 175.

[13] Berner, Seattle, 1921–1940, 241.

[14] Margaret A. Hall, “A History of Women Faculty at the University of Washington, 1896–1970,” PhD dissertation, University of Washington, 1984, chapters 1 and 5.

[15] Curtis Barnard, “Houseboys Institute Union Drive,” University of Washington Daily, February 12, 1937, 1.

[16] Gates, The First Century, 190-192.

[17] Gates, The First Century, 193.

[18] Gates, The First Century, 193-194.