by Taylor Easley

The NAACP's prosecution of three Seattle policemen accused of killing an unarmed African American man, Berry Lawson, was a watershed for civil rights cases during the Depression. Here, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reports on the case, April 8, 1938.

During Seattle’s Great Depression the black community was growing in size and strength, and the Berry Lawson case shines some light on their degree of influence. Berry Lawson was an African American twenty-eight-year-old hotel waiter who was arrested for loitering in the lobby of the Mt. Fuji Hotel in March 1938. Sometime during his arrest, Lawson received fatal injuries and died soon after. The arresting officers testified to the coroner’s jury that Lawson fell down some stairs while resisting arrest. The jury initially cleared the officers of all charges, declaring Lawson’s death accidental. Soon after this, however, evidence surfaced showing that the officers had beaten Lawson to death, bribed a witness to leave town, and procured a fake witness to say he saw Lawson fall down the stairs. This case went to the Supreme Court and all three policemen were convicted of manslaughter by a judge and jury, though two were released only moths later, a huge regional and national victory for African American civil rights in the Depression decade.

The ups and downs of this case were heavily covered by four newspapers in the Seattle area: the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Argus, the Sunday News, and the Northwest Enterprise. The Seattle P-I and the Argus had a history of mainstream, conservative reporting, while the Northwest Enterprise was an African American community newspaper and the Sunday News was run by the radical Washington Commonwealth Federation, a left-labor-communist political coalition. Each of these newspapers took a different approach to the Berry Lawson case and influenced the Seattle community in different ways, and looking at their reporting alongside courtroom testimony helps to show the way in which civil rights advocates came to win the initial case.

Police were called to the Mt. Fuji Hotel on Seattle’s Yesler Way on March 25, 1938 to investigate the attempted break-in of room at the hotel. While they were there, they arrested a drunken Native American woman named Lenora Johnson under suspicion of selling alcohol to other Indians.[1] The hotel manager, N. Hayashi, also asked the three officers to remove a young black man who was sleeping in the hotel lobby. This man was Berry Lawson, a young African American waiter who had been working at the hotel and fallen asleep after his shift ended. Officers Whalen, Stevenson, and Paschal attempted to wake him, but found this difficult and assumed he was under the influence of marijuana. They eventually woke him, and later said that it took all three of them to put the handcuffs on him. They then began to escort him to their patrol car when, according to their statement, he broke away and tumbled down a flight of stairs. He sustained heavy injuries that proved to be fatal.

A photograph from the May 24, 1938 issue of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer showing the three accused police officers, seated from left to right, Paschall, Whalen, and Stevenson.

Berry Lawson died less than an hour after this incident at the City Hospital, and an inquiry for the cause of death was carried out by a coroner’s jury, with Coroner Mittelstadt at the head. N. Hayashi testified in the police officer’s favor with a vague statement saying that as he was walking back into his office, he saw Lawson kick one of the policemen and “heard” someone strike him in return. The star witness in the policemen’s defense was unemployed day laborer James T. Franey, who testified that he saw Lawson tumble down the stairs followed closely by the three policemen. With these statements, Mittelstadt proclaimed Officers Whalen, Paschal, and Stevenson innocent of any crime in the death of Berry Lawson, despite more evidence suggesting otherwise. Since this was a police brutality case, many African Americans came to the coroner’s trial for the verdict, hoping it would be in Lawson’s favor. An African American physician, Dr. Walter S. Brown, testified that a weapon could have caused the injuries that killed Lawson; and Lenora Johnson, the Native American woman taken into custody as well, said Lawson proceeded quietly to the patrol car and when she saw him later at the police station he was “all beat up. “[2] Unfortunately, these testimonies had no effect on Mittelstadt’s decision.[3] There was upheaval in the black community in response to this verdict, since Paschal had been suspected in the past for police brutality against colored individuals.[4]

The NAACP's prosecution of three Seattle policemen accused of killing an unarmed African American man, Berry Lawson, was a watershed for civil rights cases during the Depression. Here, an article from the Northwest Enterprise from April 15, 1938, asks for support for the NAACP in their work around the case.

In the initial uproar against the three police officers, the Seattle P-I, the Northwest Enterprise, and the Argus all had similar coverage of the incident. While the Seattle P-I and the Northwest Enterprise had large headlines on the front page, advertising the corruption of police officers, the Argus posted small articles on the second or third pages. Though the Argus acknowledged the fact that the coroner’s jury ignored compelling evidence, the editors chose to push the story back into regular police news on the third page.[5] Interestingly, the Sunday News, the newspaper run by the Washington Commonwealth Federation (WCF), added some colorful commentary to their report. Along with the basic testimony by Lenora Johnson saying that she saw Lawson proceed peacefully to the patrol car, they wrote that she also

"Testified before a courtroom jammed with Negroes and whites that Lawson, as he was awakened, kicked at one of the policemen and was beat by them. They hit him around the head and stomach, and one of them remarked, she said ‘It’s too bad I haven’t got my club with me, or you wouldn’t be able to kick anyone in a long time.’ She and Lawson were handcuffed and marched down the stairs and did not fall at any time. When Lawson said he felt sick the officers said ‘you will be a lot sicker when we are through with you.’"[6]

This article must have ignited the already smoldering African American community, which seemed to be the goal of the writers at the Sunday News since none of the other newspapers mentioned the damning evidence in Ms. Johnson’s testimony. The executive director of the Seattle Urban League, a man named J.S. Jackson, decided to launch his own investigation and set out to prove that the coroner’s jury ruled incorrectly and that Berry Lawson deserved a wrongful death suit. While attempting to find a witness, Jackson also started a committee of community representatives composed of African American rights organizations, Democrats, Republicans, and Communists, of all social classes, races, and genders to protest the verdict of the coroner. The committee held protest meetings with Mayor-Elect Arthur Langlie, and put pressure on County Prosecutor B. Gray Warner to charge the police officers with the murder of Lawson. This became a real possibility a week after the coroner’s jury had met, when Jackson found his witness.[7]

Travis Downs was a white hairdresser who was unfortunate enough to have witnessed the death of Lawson. He approached Jackson on April 7th with the information about Lawson’s encounter with the officers, and it was out in the newspapers the next day. Jackson brought Downs to meet with prosecutor Warner and reported that the policemen had beat Berry Lawson severely then, after they realized Downs had seen it happen, approached and bribed him with eighty-five dollars and a train ticket to Portland, and told him to leave town. He initially obeyed the officers, and contacted them the next day, after which they picked him up and put him on a train for Portland. After Downs arrived, they sent him another fifty dollars.[8] However, Downs had a change of heart a few days later. He went straight to Jackson when he arrived back in Seattle. When the three policemen were confronted with these charges they denied all knowledge of a beating. They said that they gave Downs eighty-five dollars and a train ticket because they thought he would misrepresent the interaction between themselves and Lawson. Prosecuter B. Gray Warner filed formal charges against Whalen, Stephenson, and Paschal as soon as this evidence was presented to him. Each of the three officers was questioned individually.[9] Whalen and Stephenson were arrested for second-degree murder, and Paschal was imprisoned without being charged, because his lawyer advised him not to comment.[10]

During this stage of the case, the Northwest Enterprise covered more than just the details of the witnesses and arrests. They emphasized the assistance the Jackson gave to the police during the investigation. They also made sure to say that after Jackson became involved, more witnesses surfaced and the case started to progress. In one article, the Northwest Enterprise analyzed the giant holes in the police officers’ testimony and the evidence that was ignored by the police department, taking into account the character of the injuries that Lawson sustained.. Lawson had a large amount of defensive injuries that could not have been received if he had been wearing handcuffs, which he supposedly was. The writers also mentioned that the officers in question had been under investigation before, but had never left enough evidence to convict them.[11] The writers at the Northwest Enterprise seemed to want to generate support for the investigators and prosecutor in case against the police officers. They wrote an article aimed at the black population asking anyone who knew any information about any sort of crime to report it to Warner or any Seattle newspaper editors. The Northwest Enterprise wrote, “Negros should make it plain that they are not interested in shielding or aiding and abetting any criminal activity among Negros or any other citizen.”[12] The editors might have been using Lawson’s death as a way to galvanize the black community against corruption in the police department.

An article from the radical labor paper, The Sunday News, from April 9, 1938.

The investigators were now forming their case against Paschal, Stephenson, and Whalen. They brought Lenora Johnson in to be a material witness, and along with Travis Downs, they counted as two key witnesses in the prosecution’s case who were held in custody. There was still the common laborer James T. Franey who testified in the coroner’s jury in defense of the three officers. While the policemen posted five thousand dollars bail apiece, none of the material witnesses could afford the bail, so they each remained in jail.[13] The officers were still pleading not guilty to the accusations of murder, and Stephenson and Paschal soon requested that they be told what evidence the state had against them. What evidence was presented would determine whether they would want to be tried separately from Whalen, because they seemed to think that Whalen had presented evidence that implicated them in other crimes.[14]

On May 23, 1938, Deputy Prosecutor Henry Clay Agnew, who had been put in charge of the case, announced in his opening statement that Franey now was telling a different story, one where Whalen bribed him with two hundred and fifty dollars to testify in the inquest after Lawson’s death. He also testified that during the time he was at the police headquarters swearing in his statement, he heard Whalen and Stephenson say that Downs “had been paid a sum of money to keep quiet.”[15] Agnew also released the information that the state was proposing that Lawson had met his death within the police headquarters.[16]

In his opening statement, Agnew surmised that "After being arrested and beaten a bit at the Fuji hotel, the colored boy was taken to the police station by all three officers. He was arrested by 2:22 am, and by 2:35 he was dead on the floor of the jail elevator, having been beaten over the head at least five times with a heavily padded object. It happened this way: Paschal took the Indian woman, who was arrested at the same hotel, upstairs to the jail so she wouldn’t see the beating. Stephenson and Whalen administered the beating in the wagon room of the police station. The colored boy died from excessive concussions. One blow smashed his nose to pieces, but the other blows, though sufficient to cause death, were not so discernable. Lawson was dead by the time they got him to the jail elevator.[17]

The defense attempted to put forth a good case, using the excuse that the district was in a rough community one and the officers had done the best they could with the resources they had. The lawyer said that the officers were seen as hostile by the lowlife of the city by attempting to clean it up. They wanted to present forty-seven witnesses for their case, but the prosecution demanded that the judge limit the number, restricting the defense and the prosecution to six witnesses each.

Lenora Johnson was the first to testify for the prosecution, and testified that while the officers were beating Lawson, Whalen said “If I had a club I’d beat you up!”[18] After Downs and Franey testified, the prosecution brought in a doctor named Gale E. Wilson; he testified that one large blow, or many multiple blows were what killed Lawson. There was barely any surface damage to the skin compared to the amount that was in the brain, so the doctor concluded that it would have been impossible for the injuries to occur by falling down stairs. After the prosecution’s witnesses had been presented, the three police officers decided to put their faith in the jury and not put up a defense. Before their final decision, Agnew insisted that the jury inspect the Mt. Fuji Hotel to get a first-hand look at the premises where Lawson had supposedly died.[19] The trial ended with the closing argument from the defense, which trashed the witnesses from the prosecution.

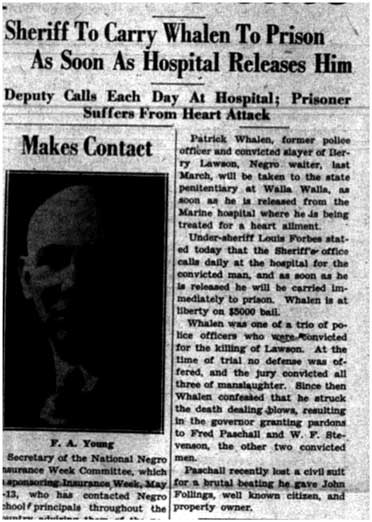

An article from the Northwest Enterprise from April 4, 1939, reporting on policemen Whalen's hospitalization. Despite the headline about the prison sentence awaiting him, Whalen was pardoned before he could serve time for the beating death of Berry Lawson.

This tactic didn’t seem to have much of an effect on the jury though, as they took fourteen hours to deliberate and found all three officers guilty of manslaughter. The judge sentenced each of the convicted policemen to twenty years in the Walla Walla state penitentiary. But it was not to be. The convicted officers never went to jail.

Officers Stephenson and Paschal were released on bail pending appeal and eleven months later received a full pardon from Governor Clarence Martin. This was prompted by a recommendation from the sentencing judge who reported new information indicating that Paschal and Stephenson had not directly participated in the deadly beating. The new chief of police even considered letting the former officers back into the department.[20] The Seattle P-I displayed pictures of both men and one of Paschal with his mother and ran them alongside a sympathetic piece about the officer’s families during their time in jail. Just eleven months before, the writers had trashed all three former officers and believed them to be guilty.

Patrick Whalen, whose guilt was clear, also escaped punishment. He had suffered a massive heart attack at the end of the trial and his sentence had been delayed during months of hospitalization. Where his colleagues received full pardons, the governor granted Whalen a "conditional pardon" on the basis of his health. He lived another twenty-five years.

The Berry Lawson Case is a tragic one, but still a victory for Depression-era civil rights. In the United States at this point in time, it would have been unthinkable for three white police officers to be arrested for the death of an African American despite incriminating evidence. The fact the the police were both arrested and convicted speaks to the rising political power of the African American community and the coalition they were able to build to prosecute the officers.

Copyright (c) 2009, Taylor EasleyHSTAA 353 Spring 2009 (small revisions 2020)

[1] “Woman Says Cops Beat Negro Youth Before His Death,” The Sunday News, April 2, 1938, p.1.

[2] “Police News,” Argus, April 2, 1938, p.3.

[3] “Inquest Jury Decides Negro Died From Fall,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 1, 1938, p.1.

[4] “Trio Jailed Over Death of Prisoner,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 8, 1938, p.1.

[5] “Police News.” Argus, April 2, 1938, p.3.

[6] “Woman Says Cops Beat Negro Youth Before His Death,” April 2, 1938, p.3.

[7] Quintard Taylor, “The Forging of a Black Community” (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994), p.97.

[8] “Police News,” Argus, April 9, 1938, p.3.

[9] “Trio Jailed Over Death of Prisoner,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 8, 1938, p.1.

[10] “Police Facing Murder Charge After Negro Youth Dies in City Jail,” Sunday News, April 9, 11938, p.1.

[11] “NAACP Vice President Uncovers Damaging Evidence In Lawson Case,” Northwest Enterprise, April 8, 1938, p.1.

[12] “NAACP Vice President Comments On Lawson Case,” Northwest Enterprise, April 22, 1938, p.1.

[13] “Police News,” Argus, April 23, 1938, p.3.

[14] “Police News,” Argus, April 30, 1938, p.3.

[15] “State Claims Officers Slugged man to Death,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 24, 1938, p.2.

[16] “State Claims Man Slain in Jail Beating,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 24, 1938, p.1.

[17] “State Claims Officers Slugged Man to Death,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 24, 1938, p.2.

[18] “Woman Tells of Beating At Police Trial,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 25, 1938, p.1.

[19] “No Defense to Be Offered On Death Trial,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 27, 1938, p.1.

[20] “Two Ex Policemen Given Pardons By Governor Martin,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 1, 1939, p.1.