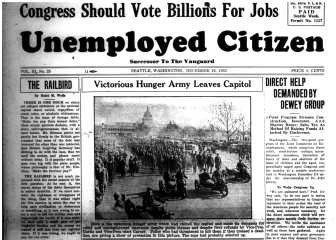

Called the Vanguard when it began publishing in 1930, the lively weekly became the Unemployed Citizen after the Unemployed Citizens League was launched in the summer of 1931.As America entered the 1930s, the entire nation felt the grim impacts of the Great Depression. Workers in Washington State, historically home to resource extraction industries like timber and mining, suffered under especially poor economic conditions as the demand for raw materials plummeted and construction projects across the country ground to a halt. Local and state officials across the Pacific Northwest struggled to meet the needs of residents, often failing to provide them with even the basics of life, such as food, clothing and shelter.

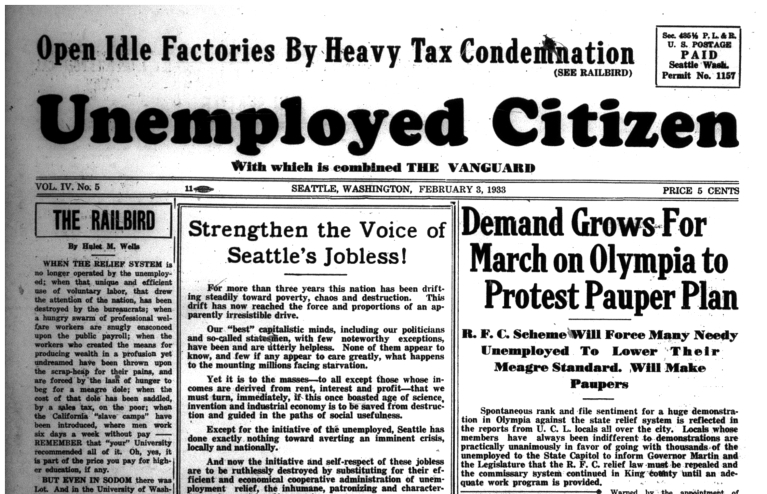

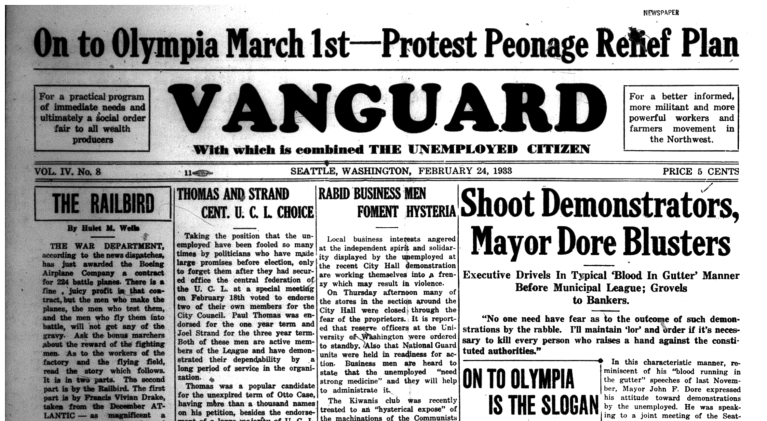

Amidst the economic and social turmoil, new radical publications began to appear, calling for direct action on the part of citizens in order to bring about political change. One of these newspapers, the Vanguard (re-named the Unemployed Citizen in the summer of1931), played a pivotal role in organizing a series of rallies in Washington’s state capital Olympia. Published by the Unemployed Citizens’ League (UCL), the paper ran eye-catching headlines in support of its causes, such as “Demand Grows for March on Olympia to Protest Pauper Plan.”[1] Since state officials were not providing much in the way of aid to those hurt by the Depression, the Vanguard and the UCL decided to bring the people’s demands straight to the seat of power. As they experienced record high unemployment, Washingtonians grew restless and a movement for change began to emerge. [2]

To combat the joblessness, which exceeded 50% in many neighborhoods, labor organizations took shape at an impressive rate. Unfortunately, many of these groups suffered from either poor organization or a lack of sufficient support and could not make progress. In July 1931, socialists Carl Branin and Hulet Wells, who published the Vanguard, decided to create their own “citizen-action group” to demand reasonable wages and relief for those out of work.[3] Fifty individuals attended their first meeting in West Seattle and the Unemployed Citizens’ League was born. From the beginning, Branin and Wells refused to accept charity as a solution, instead insisting that such benefits remain reserved for those who could not work - as opposed to those who were perfectly capable of performing jobs. In September 1931, the Vanguard featured an article highlighting the UCL’s commitment to “not depending upon the promises of city and county politicians or the business brains of the community to take care of the unemployed during the trying days that are just ahead,” instead suggesting the unemployed look to one another for assistance. [4] This piece foreshadowed the initiatives soon be enacted by the UCL.

The UCL branches of Seattle 1931-1933. View UCL Seattle Branches in a larger mapAt the end of 1931, with 22 branches across Seattle, the League expanded its services to include “self-help program[s] by which to exchange goods and services.”[5] The idea of self-help stemmed from the League’s ongoing lack of support from local and state government. Fed up with the inconsistency, the UCL took matters into its own hands. Through its various branches, the UCL set up a network of eighteen commissaries to assist families struggling to make ends meet. To further help the cause, Seattle Mayor Robert Harlin created the Commission on Improved Employment (better known as the Harlin-Dix Commission), which was to be headed by I.F. Dix. In December 1931, the Commission provided food to the commissaries for distribution to the needy. That same month, the UCL won a second victory, when the city enacted a $4.50 per day wage for unemployed workers.

Soon though, the gloom of 1932 overshadowed the promise of 1931. By March, headlines in the Vanguard turned decidedly negative, with one reading that the “Senate Refuses Food to Hungry.” Articles reported that a family of four had to survive on less than 50¢ worth of food per day. Of the $472,000 given to the UCL by the city in January, with the intent of lasting through April, only $180,000 remained by early March. Although running very low on money, the commissaries continued to be a success with 8,493 families registered at 22 locations. As for finding jobs, less than half of the 12,100 people listed for work with the UCL the previous fall had found a job by March of the following year.[6] Like communities across the country, the League and its membership struggled to sustain themselves.

In April, League members got a morale boost when three of their preferred candidates won election to Seattle city offices – an outcome aided by high turnout on the part of UCL voters.[7] The euphoria of victory, however, wore off quickly as demands for food grew. The idea of creating food co-ops began to gain traction, with UCL members inspired by foreign countries that had “built up a huge system of this sort with no great financial resources on the part of its people,”[8] This new development would be one of the sparks that triggered the mass protests known as Hunger Marches.

During the summer of 1932, the United Producers of Washington attempted to organize a march on Olympia to demand that the legislature hold a special session to address the state’s lack of assistance to the unemployed. Simultaneously, mayors representing forty Washington cities held a meeting in Seattle, also to petition for a special session. Tax revenues and increased public funding were high on their list of concerns. Unfortunately, for the petitioning mayors and the United Producers, Governor Roland Hartley proved less than sympathetic. A self-made man, he opposed taxes, unions, and most progressive reforms. He was not a fan of socialists, communists, or labor organizations in general. Governor Hartley did not reply to letters from Carl Branin and he refused to speak with the mayors.[9] As a result, the UCL decided that the League would march on Olympia on July 4, 1932. The Vanguard hoped to illicit support with cries of “On to Olympia!” and even released a special issue to advertise the upcoming action.

The UCL quickly discovered however, that it was not the only entity seeking to organize support for a march on the capital. The Communist-affiliated Unemployed Councils, a less-popular rival organization, decided to participate in the mobilization as well – an unwelcome ally in the eyes of many League members and supporters. Desiring no connection to the Communist Party, some UCL members abandoned the march. A group of Communists nonetheless went ahead with the action. On July 3, 1932, they arrived in Olympia and encountered a meeting party of police and highway patrol officers, who refused the marchers entrance to the city. They escorted the Communists to Priest Point Park, about two miles north of the capitol dome, claiming that Olympia was “not prepared to care for an influx of dependent people.”[10] Governor Hartley was conveniently out of town, so the demonstrators were unsuccessful in meeting with him.

The following day, the Fourth of July, about a thousand members of the United Producers, the UCL and the National Council for the Unemployed arrived on the capitol grounds as well. Sitting on opposite sides of the steps, the groups quickly engaged in a fistfight when an uninvited group of Communists “stepped to the front…with an array of flaming placards.”[11] After the incident, many participants received free gasoline from the city as an incentive to leave town while 50-100 people chose to camp out at Priest Point Park and wait for the Governor’s return. On July 5, the remaining marchers were finally able to meet with Governor Hartley, though they did not reach an agreement on relief. The primary result of the July 4 march was an increase in tensions between the UCL and the Communist Party. Despite the difficulties with state government, by October of 1932, the UCL food co-ops were in full operation and the Vanguard had upped its frequency to become a weekly newspaper in order to meet increasing demand.

October 1932 was an important period in the history of the Hunger Marches. Early that month, Don Evans and J.A. Earley, two King County commissioners, took $10,000 worth of berries from the UCL stores. Totaling some 175,050 pounds, the berries had been picked by members of fifteen local branches, who then donated them to the UCL for use in the co-ops to feed the unemployed. The commissioners obtained and held the berries, with a court-issued restraining order, arguing that the berries were not meant to be used for such purposes (based on unclear evidence). From the League’s perspective, it was a theft. The Vanguard issued a statement, which read: “The UCL is reorganizing to meet this attack. Its function now, as never before, is to become a militant organization of protest. It places full responsibility for the relief of the destitute upon the shoulders of the public authorities.”[12]

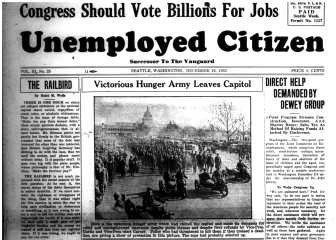

The actions of the commissioners shifted the UCL’s focus and a new militant morale took over. The next issue of the Vanguard claimed that Commissioner Earley was stealing other foods from the Capitol Hill commissary as well.[13] In late November, the UCL re-gained control of the berries, though other missing food was never recovered. That month’s issue of the Vanguard also advertised for a Hunger March that was to take place in Seattle on December 5, coinciding with a day of national action and marches.[14] Following the Washington D.C. hunger march, the Vanguard headlines carried the uplifting message that a “Victorious Hunger Army Leaves Capitol.”[15]

The successor to the Vanguard, the Unemployed Citizen highlighted news of poverty activism and the unemployed from throughout the nation, including a 1933 march in Washington, D.C. Inspired by the successful outcomes of the national marches of December, the United Front Unemployed (a coalition of the UCL and other labor organizations) formed with the purpose of marching on Olympia. On January 17, 1933, about 1,000 men and women met at the capitol to protest the McDonald Bill, which would take the control of commissaries out of their hands and into those of an assigned social worker, denying the unemployed an important measure of agency over their own well-being and removing a powerful organizing tool for the UCL. Upon their arrival at the capitol, UFU members found State Troopers patrolling the hallways as well as a slew of locked doors and elevators. Some local businesspersons allowed the women and children to sleep in vacant stores. One group of volunteers passed out beans and coffee, which made many of the marchers sick. Signs reading “To Hell with Olympia Beans!” soon joined myriad others.[16] After brief negotiations and promises of peace, a delegation of 25 met with the newly elected Governor, Clarence D. Martin.[17] Although the delegates were received cordially, the demands of the demonstrators went unmet.

The relative failure of this Olympia Hunger March inspired the UCL to regroup and pursue the same tactic again at a later date. By February, according to the Vanguard, delegates from the various Seattle branches were “unanimously in favor of going with thousands of the unemployed to the state capitol to inform Governor Martin…that the RFC relief law must be repealed and the commissary system continued in King County until an adequate work program is provided.[18]

Ultimately, organizers selected March 1 as the time when unemployed workers representing all industries and all regions across the state of Washington would meet in Olympia. In a memo to the “brothers” of Olympia and Thurston County, the State United Front Committee of Action stated that the “demands of the Hunger March are for repeal of the vicious McDonald bill, for emergency cash relief, [and] for more adequate relief to all the destitute in the form of Unemployment insurance.”[19] Among the key demands was a provision for unemployed citizens to receive $10 per week and an additional $3 per dependent. The four hundred delegates who were present at a planning meeting, representative of 87 branches of the UCL and other organizations within the coalition, agreed to this strategy. Their goal was to get 5,000 delegates to show up at the capitol. A committee was set up to handle arrangements in Olympia, including procuring food and lodging for the marchers. The next issue of the Vanguard featured the headline, “On to Olympia on March 1st.”  Despite warnings from officials in Olympia and Seattle, a broad coalition of groups came together to organize a march on the state capitol to protest the conditions faced by the unemployed and their families.

Despite warnings from officials in Olympia and Seattle, a broad coalition of groups came together to organize a march on the state capitol to protest the conditions faced by the unemployed and their families.

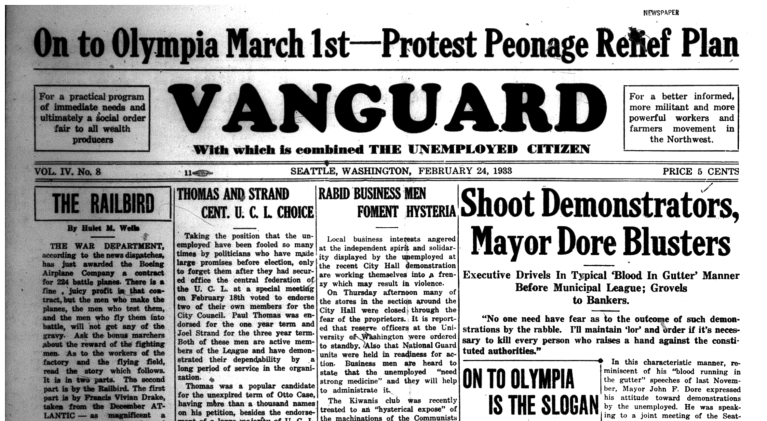

Soon, organizers had received word from the committee in Olympia that the city would not provide food or lodging to the hunger marchers, whom they expected to form a mob and cause trouble. Olympia authorities did not want “seditious and anarchistic demonstrators within the city.”[20] The UCL expected trouble with Olympia city officials, but the actions of Seattle Mayor Dore, who threatened to block congregating marchers from passing through his city, surprised them. Despite these types of threats, the marchers refused to be intimidated and chose to proceed with their plans.

On the morning of Wednesday, March 1, 1933, a group of appointed delegates from the northern counties of Washington met in Seattle - despite Mayor Dore’s admonitions against such gatherings. Together this group traveled to Olympia in two hundred cars and trucks. As they traveled southbound, delegates from other counties joined the caravan. The number of people grew to about 3,000 by the time the group reached their destination.[21]

Consisting mostly of men, this traveling group did have about three hundred women and fifteen children within their ranks.[22] A blockade met the marchers as they approached the city limits, courtesy of Olympia Sheriff Havens and one hundred fifty self-proclaimed American Vigilantes. As per the ultimatum given by Governor Martin, Olympia Police Chief Cushman yelled at the marchers, “Get out in 30 minutes or be thrown out!”[23] The marchers, all of whom had agreed to make this a peaceful rally, refused to leave and were subsequently corralled into Priest Point Park. According to reports in the Vanguard, the three thousand marchers were held at the park in the cold rain (and the mud that came as a result) with no shelter. While the hunger marchers huddled around fires, singing and drinking coffee, the American Vigilantes parked “for a mile leading to the entrance of the park,” and were equipped with machine guns and “other death-dealing equipment.” After 28 hours, the marchers were allowed, by “lor’n order” forces, to parade through the city. The parade did not have approval to stop at the capitol, nor could the delegation speak with the governor or legislature at the current joint session. The marchers were directed back to Priest Point Park and, at this time, decided that, “it would be folly to subject themselves to the armed attacks of state Cossacks, deputy sheriffs and vigilantes, numbering 700 men, and took their departure in organized, orderly fashion for their homes in various parts of the state.”[24]

Despite the efforts of the UCL, a “close check-up of the unemployed present in Olympia for the demonstration sets the figure at 4000,”[25] the McDonald Bill still went into effect shortly thereafter. In accordance with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, a new agency, the Washington State Emergency Relief Administration, was formed to help provide aid to those in need. In the aftermath of the hunger march, UCL members believed that the public was largely misinformed about what had occurred in Olympia and the goals of their movement. For example, according to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the women and children involved in the march had been permitted to sleep in the old state house while men set up camp in vacant stores – a complete contradiction to the reports provided by the Vanguard.

The March 1933 hunger march was, at the time, counted as a failure. The marchers did not meet with Governor Martin, nor were they successful in making a statement at the capitol building. As a result, League membership declined at an accelerated pace, with those members who did remain active growing increasingly militant. Yet despite these setbacks, the actions of local authorities could not erase or deny the underlying unity and power displayed by this group of working class individuals. The three thousand (or more) delegates who participated in the march were members of 114 working class organizations – a coalition of the Unemployed Citizens League, the United Producers of Washington, the Unemployed Council, and the United Farmers’ League. Often in opposition, caused by constantly vying for the same member pool, these groups worked together on that day to host “the most impressive mass movement in Seattle since the days of the General Strike.”[26] This coalition brought attention to the successful organizational skills of such groups and ultimately, demonstrated the ongoing power of the working class.

[1] Vanguard, February 3, 1933. Througout this paper and the notes, the paper is referred to as the Vanguard. Its name was changed to the Unemployed Citizen in 1931, but for purposes of continuity, the name Vanguard is used throughout this report.

[2]According to the Vanguard, unemployment in several Seattle neighborhoods in October 1931 hovered well over 30% including: Olympic Heights, 52%; Ballard, 34%; Georgetown, 75 to 80%; and White Center, 83%. The newspaper also argued that the 35,000 individuals reported unemployed by the Seattle mayor’s office represented a decidedly low estimate. Vanguard, October 1931.

[3] Terry R. Willis, Unemployed Citizens of Seattle, 1930-1933: Hulet Wells, Seattle Labor, and the Struggle for Economic Security (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Washington, 1997), p. 196.

[4] Vanguard, September 1931.

[5] Terry R. Willis, Unemployed Citizens of Seattle, 1930-1933, p. 202.

[6] Vanguard, March 1932.

[7] Vanguard, April 1932.

[9] Terry R. Willis, Unemployed Citizens of Seattle, 1930-1933, p. 231-232.

[10] “200 Jobless, Cold, Hungry Reach Olympia.” Post-Intelligencer, July 4, 1932.

[11] Terry R. Willis, Unemployed Citizens of Seattle, 1930-1933, p. 236.

[12] Vanguard, October 21, 1932.

[13] Vanguard, October 28, 1932.

[14] Vanguard, November 25, 1932.

[15] Vanguard, December 16, 1932.

[16] Gordon Newell, Rogues, Buffoons and Statesmen (Seattle: Superior Publishing Co., 1975), 369.

[17] Shanna B. Stevenson, Olympia, Tumwater, and Lacey: A Pictorial History (Virginia Beach, VA: The Donning Co., 1985, rev. 1996) 186, 191.

[18] Vanguard, February 3, 1933.

[19] State United Front Committee of Action, memo to Citizens of Olympia, 1933, Eugene V. Dennett Papers, Accession 3917-2, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division, Box 1, Folder 3.

[20] Vanguard, February 24, 1933.

[25] Vanguard, March 10, 1933.

Despite warnings from officials in Olympia and Seattle, a broad coalition of groups came together to organize a march on the state capitol to protest the conditions faced by the unemployed and their families.

Despite warnings from officials in Olympia and Seattle, a broad coalition of groups came together to organize a march on the state capitol to protest the conditions faced by the unemployed and their families.