by Pamela Schwartz

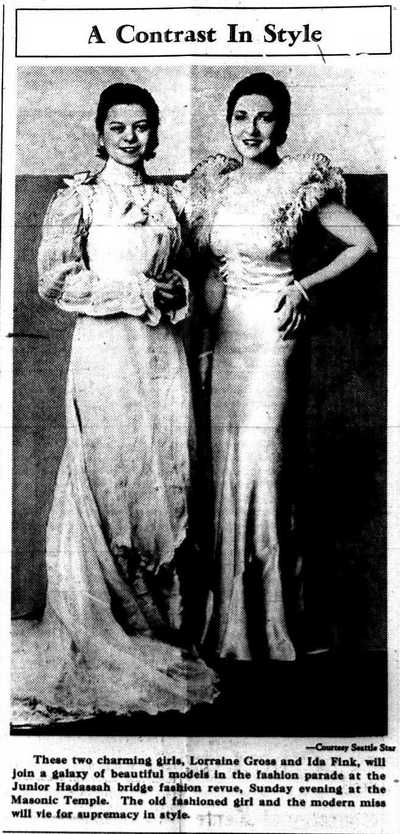

The Jewish Transcript, May 1934, p.29.

The Jewish Transcript, May 1934, p.29.

The Great Depression challenged traditional gender roles for many women. Some were pulled into the labor market as unemployment destabilized the bread-winner status of men and broke apart families. Others were pushed out of jobs when employers decided to save them for men. As poverty escalated, many women took on new roles in their communities, some drawn into philanthropic work, others into political activism. Meanwhile, celebrities like Eleanor Roosevelt and Amelia Earhart demonstrated new models of womanhood.

How did Jewish women in Seattle negotiate the Great Depression? An investigation of the Seattle Jewish Transcript from 1933 until 1938 offers some indications. The weekly newspaper, which had served the community since 1924 and continues to serve it today, reveals stories of women balancing roles in the home and community and also balancing cultural expectations. Jewish women demonstrated great strength and spirit while struggling with their desire to assimilate and integrate into the mainstream community.

The Jewish Transcript had been founded in 1924. Publisher Herman Horowitz declared in the first issue that its purpose was to “advocate the highest ideals of Judaism, linked with the most strenuous Americanism.”[1] The dual agenda remained evident in the 1930s.The newspaper emphasized that cultural inheritance was the most significant means of survival for Jewish women. By instilling Jewish ideals, women understood they could preserve their traditions and values, allowing for their faith and culture to survive for future generations. However, in order to earn the respect of their peers and gain acceptance into mainstream society, women needed an education. In the October 1937 issue of the Jewish Transcript, education was mentioned as the defensive tactic that would help to protect oneself against anti-Semitic hostility: “an education for young women allows for an interest in Jewish affairs in a world of strife and hardships so that she would be armed with the only ammunition a Jew possess: knowledge.”[2] Knowledge provided the tools to defend themselves in a community faced with Anti-Semitism. Education gave women influence and respect while also guiding them to the pathway of assimilation.

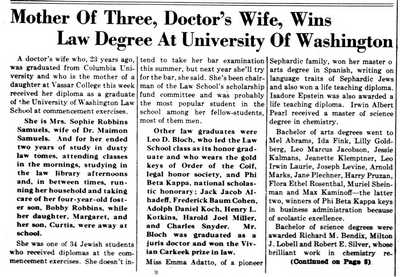

The Jewish Transcript, November 1934, p.34.

The Jewish Transcript, November 1934, p.34.

The newspaper largely reinforced traditional images of women as wives and mothers, while also emphasizing the importance of education, up to a point. Young men went to college, found jobs and married. Young women who chose to attend college often were encouraged to leave school to become housewives and mothers. The Jewish Transcript reported how cupid cut short many Jewish women’s educations at the University. [3] A well-educated and cultured woman continued with her studies until the day she found a husband and for that reason, many women did not graduate college. Marriage presented a double standard as unmarried men were regarded positively as bachelors and unmarried women were viewed negatively as spinsters. Mothers wanted their daughters to marry early, their sons to marry late in life. In a April 1935 issue, Transcript columnist Gertrude Berg comments “ a girl who reaches the age of 25 and is still unmarried is bewildered if not open, then at least in the mother’s secret heart, while the boy who is married at age 25 is pitied”. [4] She added that “a son was an economic asset to his parents while a daughter was a liability, another mouth to feed, until marriage of course.”[5]

Like many community newspapers in the 1930s, the Transcript published few stories about poverty or even about working class Jewish families. The social pages, advice articles, and lists of clubs and activities catered mostly to the prominent and socially active members of the community. Parties and dances gave much needed relief to the Jewish community during the Depression era. The Personal and Social pages of the Jewish Transcript burst with news of parties for every occasion. Planning and arranging these events was part of middle-class Jewish women’s identity. Whether it was dining with out of town guests or a dinner party, women took their responsibilities seriously. In the May 1934 Social and Personal Events section of Jewish Transcript the details of a soiree were described as “Tall vases filled with blue delphinium against a backdrop of ivory. The hostess and her honored guests all delightfully smart in long, pretty frocks; Mrs. Silver’s in black lace and Mrs. De Lue in black chiffon.”[6] Vacations abroad gave another reason for a dinner party and for a column in the newspaper. According to the Jewish Transcript “For the pleasure of Judge Samuel R. Stern, who left Saturday on a world tour, Mr. and Mrs. Albert Weinberg were hosts at a delightful Valentines dinner party at their home on Tuesday of last week. Ten guests enjoyed their hospitality.” [7] These gatherings exhibited the good taste and respectability of Jewish society and the Jewish Transcript celebrated evidence of Jewish status and acceptance in elite social circles.

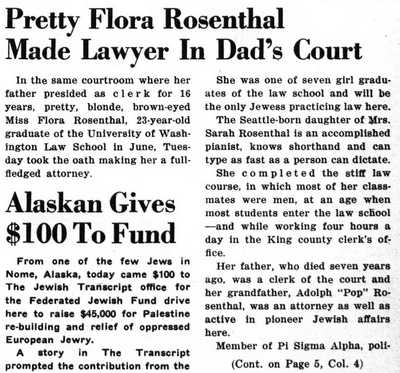

The Jewish Transcript, November 1934, p.37.

The Jewish Transcript, November 1934, p.37.

Social clubs gave Jewish women a new independence and much needed freedom from their home. However with anti-Semitism being at its peak during the 1930’s, most social clubs imposed restrictions and quotas on Jews. Most local country clubs, athletic clubs, and women's clubs barred Jews and other minorities from joining, but the Jewish community hosted a wide array of parallel organizations. Through these opportunities, Jewish women developed their social networks, embraced their womanhood, and found admission into “good society”.

The social life of younger women was also well publicized in the Transcript, which featured news of popularity contests and beauty competitions for young, single women including the “Queen of the Purim festival”, “Miss Popularity” and “Miss B’nai B’rith”. Judging these events were local bachelors, giving an opportunity for the matchmakers of the community to perform their magic and set up single Jewish men and women. Describing the beauty queen’s performance, the Jewish Transcript reported “the shy, beauteous misses passing before the expert eyes of the somewhat flustered judges. Followed by a hurried consultation, the judges chose Helen Poplack, a 21 year old dark, slim University of Washington honors graduate. Her statistics were: weight 121 pounds, height 5’4” with black wavy hair, brown eyes, broad, friendly smile and sparkling white teeth”.[8] According to the Jewish Transcript, the only requirements for beauty contestants were a bathing suit and a smile.[9] Local Jewish auxiliaries and non-profits hosted these events. By adding a beauty competition to their agenda, the groups increased attendance and raised additional funds for philanthropic activities.

The Jewish Transcript, Arpil 1933, p.35.

The Jewish Transcript, Arpil 1933, p.35.

Femininity, style, and beauty were the focus of many women. Images from Hollywood and motion pictures romanticized the Anglo-Saxon female, depicting blonde hair and fair skin as the standard of beauty. Hollywood rarely if ever portrayed their leading ladies as dark haired, olive skinned, ethnic beauties. Aspiring to be like the storybook blonde, Jewish women dyed their hair, indulged in the newest beauty products, wore the latest fashions and followed the advice of experts. For example, a front page commentary in the Jewish Transcript quoted the ambassadress of beauty, Madame Rubenstein, as arguing that, “Jewish women should curb their appetites to keep their beauty and not allow themselves to get flabby. They should control their appetites. They like good food and eat a lot of it”.[10]

The Transcript advice columns modeled a traditional understanding that young women should first of all aspire to be good mothers. According to the October 1937 issue, “The Jewish girl of the 1930’s was the future Jewish wife and mother and it is she who would mold and influence her children’s lives”. The value and significance of a good education stemmed from thousands of years of traditional teachings in Judaism. A September 1933 article titled “Mother’s Duty” argues “The Jewish woman since the earliest periods of our history has taken upon herself the task of bringing up the children. It was always the mother who saw to it that her young boy or girl should be taken to Hebrew school at the proper age, and it was she who looked after his welfare day by day.” [11] Advice columns also advocated the virtues of staying home to raise children, volunteering in classrooms and attending PTA meetings. [12] Mothers wanted a good life for their children and placed a high value on education. Thus as the overseers, they were confident that their children would succeed in life.

Fathers were not expected to take an active role with their children’s secular or religious education beyond an occasional appearance at school. On these nights, the mothers of the PTA would provide an evening of entertainment for the men of honor, the fathers. In an article titled “Dad’s Night at Talmud Torah”, the Jewish Transcript reported that it was the father who not only paid the bills throughout the year but was also to be treated as “King for the night” at school. [13] Gender roles as depicted in the Transcript made fathers the sole breadwinners for their families, while the mother’s responsibilities were in the homes and with the children.

The Jewish Transcript, May 1, 1935, p.1.

The Jewish Transcript, May 1, 1935, p.1.

The newspaper featured articles that criticized women who chose careers outside the home. Mrs. Ida Hill, founder and first President of the Oakland Council of Jewish Women, provided stern recommendations to the women of the Jewish community to forgo the opportunity to have a career. In an article addressing the Council of Jewish Women in Seattle, the Jewish Transcript, reported “She may be a globetrotter, a club woman, lecturer and a woman who does things, but Mrs. Ida E. Hill still believes that although the fair sex doesn’t stop wearing trousers, even in the modern world, no woman should give up her home for a career”[14] therefore reinforcing the opinions that the mother’s job was to nurture and parent their children and in turn, they would teach their children the importance of good values, traditions and gender roles. Jewish women should be housewives and mothers first, career women second.

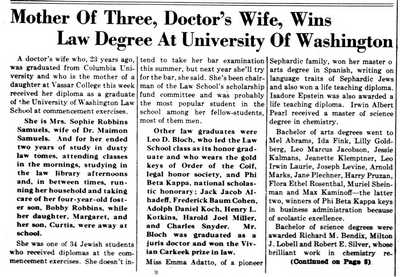

The Jewish mother who chose to return to school was told to balance her education with her home life. A good example of this was in a May 1935 article: “A doctor’s wife, who, 23 years ago graduated from Columbia University, received her diploma from the University of Washington law school. She has ended two years of study in law tomes, attending classes in the morning, studying in the law library in the afternoon while in between times, running her household and taking care of her four year- old son.” [15]

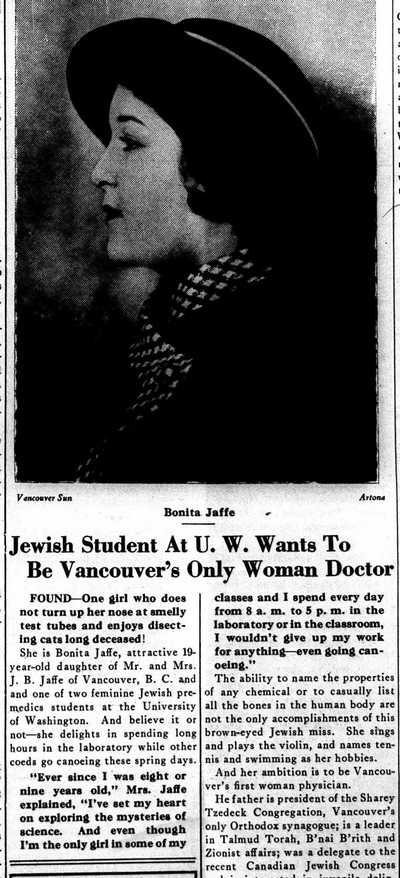

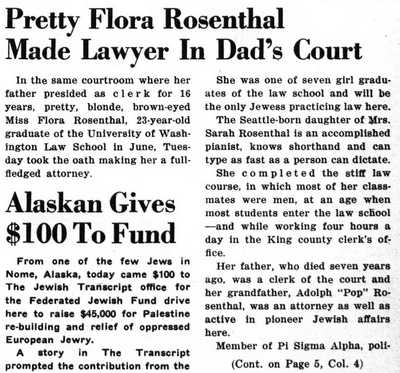

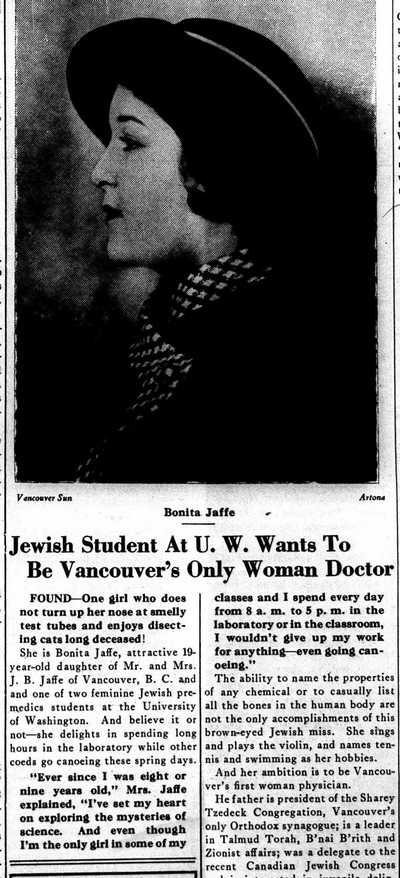

The newspaper did occasionally profile women who broke the stereotypical image of the female of the 1930’s by choosing to be career women instead of full time housewives, but the tone was often patronizing. Regardless of their achievement as the only female graduates in their law class or starting up their own medical practice, their identities as serious career women were constantly feminized in a male dominated world. For example, according to the Jewish Transcript, “Bonita Jaffe, an attractive, brown eyed 19 year old was one of 2 female pre-med students at the University of Washington; and believe it or not, she delights in spending long hours in the laboratory while other coeds are canoeing”.[16]

Another article describes Flora Rosenthal as one of only seven women to graduate law school from the University of Washington in 1937 and the only Jewish woman to practice at a Seattle law firm. She is “the pretty, blonde, brown eyed graduate, who is an accomplished pianist, knows shorthand and can type as fast as one can dictate”. [17]One of only two female eye specialists in Seattle, the Jewish Transcript described Dr. Hanna Kosterliz as “the modest, brown-eyed Doctor who opened up her own practice in Seattle.” [18]and “Marian Closser, a trim, fair haired young woman of 31 who worked her way up from 10 years as a stenographer to one of the leading figures in her field. In 1933 she was also the only woman delegate at Chicago’s National Association of Health and Accident Managers convention”.[19] These are examples of women who took the unconventional paths towards personal growth and independence, only to be marginalized and feminized by society.

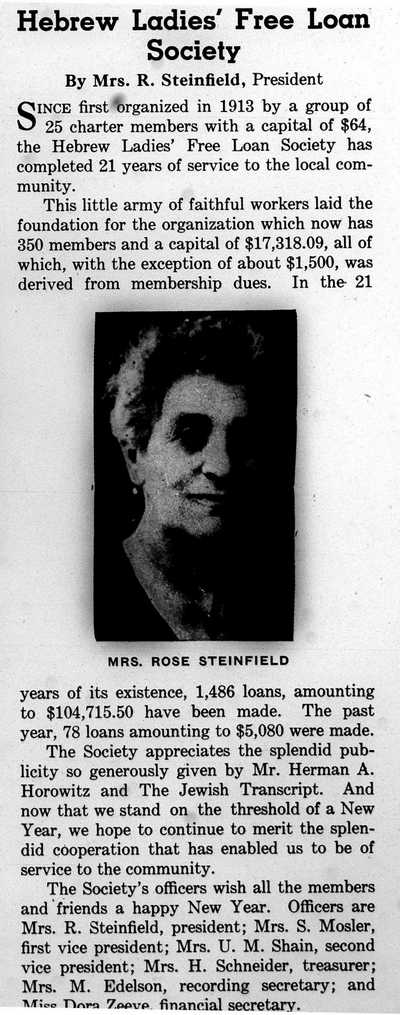

Jewish Transcript, April 1935, p.1.

Jewish Transcript, April 1935, p.1.

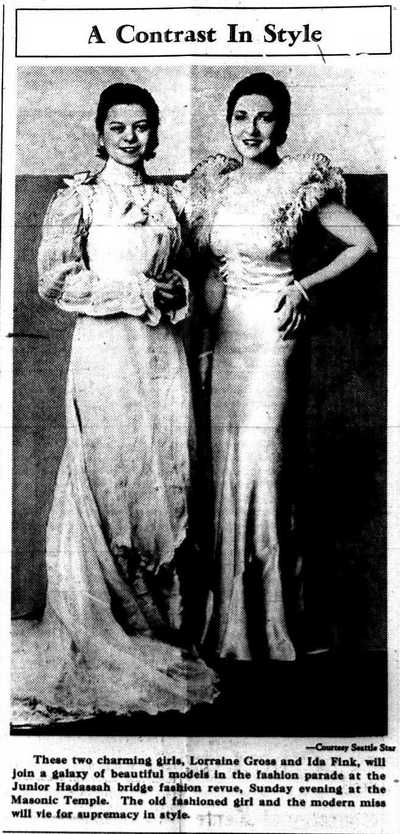

On the other hand, the newspaper celebrated women’s involvement in philanthropic activities, which was long supported by Jewish law and custom and further encouraged by the economic hardships and world events of the 1930s. The Hebrew term “Tikun Olam” (to repair the world) taught charity and social justice. Women joined Hadassah and the Jewish Junior League, organizations formed to raise money and awareness for both Jews in the United States and overseas. Women led the drive by boycotting goods from Germany, raising money for the endowment of hospitals and organizing clothing drives for the homeless. They joined the Emma Lazarus Society, an organization that raised money for citizenship lessons, scholarships and social services.[20] Women also joined auxiliaries of the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith. Its mission to “stop the defamation of the Jewish people and secure justice and fair treatment to all” [21] gave the Jewish community the tools to fight for civil rights for both Jews and all people.

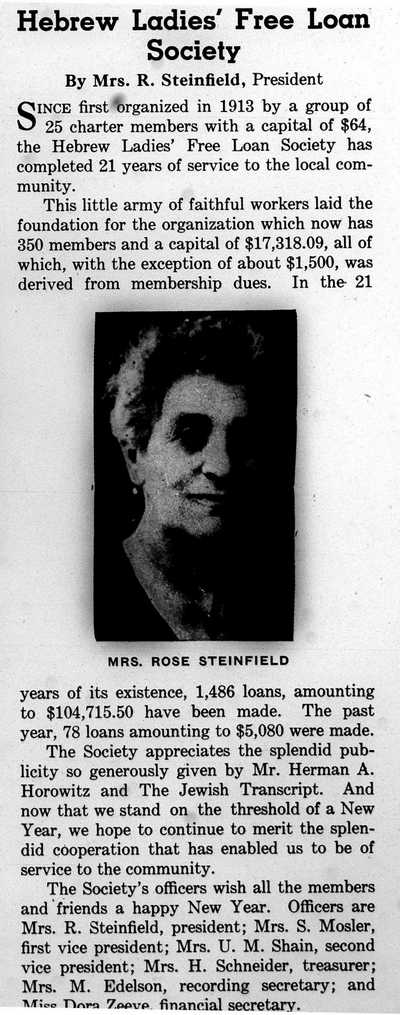

The Hebrew Ladies Free Loan Society was founded to offer interest-free loans to Jewish merchants to help them become established in the retail business community. Most small Jewish immigrant businesses could not otherwise obtain loans from commercial banks. This financing practice was based on biblical principles, and also helped to combat prevailing anti-Semitism by demonstrating that Jews were not usurers and that they ensured the wellbeing of their own people. The nature of the loans changed over time from small business loans to aid for widows and children.[22] The Hebrew Ladies Free Loan society founded on the principals and the laws from of Old Testament, given in Exodus 22:24: “If you lend money to my people, to the poor among you, do not act toward them as a creditor, exact no interest from them.” [23]Philanthropic responsibilities proved important as Jewish women demonstrated their concern and care for all communities, both Jewish and non-Jewish alike. Jewish women converted their love of social justice into action and created another opportunity to integrate into the Jewish community and embrace the community at large.

The Jewish Transcript provides a selective view of women’s lives and commitments in the 1930s, leaving out working class women and saying relatively little about those women who challenged traditional gender norms either through career choices or by joining radical causes and taking political leadership roles. But we do get a clear sense of how this important newspaper wanted women to behave and of how it celebrated women as essential in the building and preservation of the Jewish community. As mothers and housewives, they were the towers of strength in their homes. As beauty queens, proud of their identities, they strove to assimilate in a world that viewed beauty different from their own. As college graduates and professionals, they excelled as they competed to define themselves as professional women in jobs normally reserved for “men only.” And finally as activists, integrating their love and respect for religion, social justice and community, they worked tirelessly to make a difference in the world.[24]

Copyright (c) 2014, Pamela Schwartz

HSTAA 105 Winter 2013

[2] “Mother’s Praise Hebrew School Learning,” The Jewish Transcript, Oct. 3, 1937

[3] “Only Woman Delegate to Chicago Conclave,” The Jewish Transcript, June 16, 1933

[4] Berg, Gertrude, “A Marginal Note,” The Jewish Transcript, April 3, 1935

[5] Berg, Gertrude, “A Marginal Note,” The Jewish Transcript, April 3, 1935

[6] “Social Engagements,” The Jewish Transcript, May, 1934

[7] “Social Engagements,” The Jewish Transcript, Feb. 21, 1934

[8] “They Seek Title,” The Jewish Transcript, June 14, 1933

[9] “Beauties to Parade at B.B. Picnic,” The Jewish Transcript, Aug. 4, 1936

[10] “Jewish Women Should Curb Their Appetites,” The Jewish Transcript, May 19, 1933

[11] “Mother’s Duty,” The Jewish Transcript, Sept. 1933

[12] “Mother’s Duty,” The Jewish Transcript, Sept 1933

[13] “Dad’s to be School Guests,” The Jewish Transcript, Oct. 3, 1937

[14] “Don’t Give Up Home for Career, Advise of Visiting Woman’s Leader,” The Jewish Transcript, Sept. 1933

[15] “Mother of Three, Doctor’s Wife, Wins Law Degree at UW,” The Jewish Transcript, May 1935

[16] “Jewish Student at UW Wants to be Vancouver’s Only Woman Doctor”, The Jewish Transcript, May 1934

[17] “Pretty Flora Rosenthal Made Lawyer in Dad’s Court, The Jewish Transcript, Aug. 2. 1937

[18] “Modest Brown-Eyed Dr. Hanna Kosterliz,” The Jewish Transcript, March 3, 1937

[19] “Only Woman Delegate to Chicago Conclave,” The Jewish Transcript, June 16, 1933

[20] American Jewish Committee, “American Jewish Year Book”, Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1919. Print

[21] “About the Anti-Defamation League,” ADL, http://www.adl.org/about-adl/

[22]Goldring, Deborah R. “Jewish Free Loan Societies in the US, 1880’s – 1920’s,” Florida Atlantic University,

[23] Felberg, Michael, “Lending A Helping Hand”,The Jewish Federations of North America. Web. 7, May 2013

[24] “A Woman of Valor,” The Old Testament, Proverbs 3:13-18

The Jewish Transcript, May 1934, p.29.

The Jewish Transcript, May 1934, p.29.  The Jewish Transcript, November 1934, p.34.

The Jewish Transcript, November 1934, p.34.

The Jewish Transcript, May 1, 1935, p.1.

The Jewish Transcript, May 1, 1935, p.1.

Jewish Transcript, April 1935, p.1.

Jewish Transcript, April 1935, p.1.