by Emma Lunec

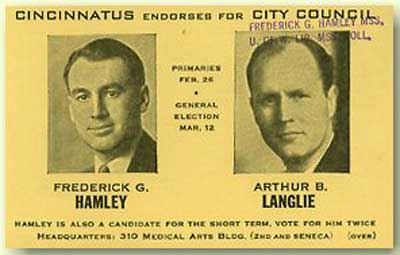

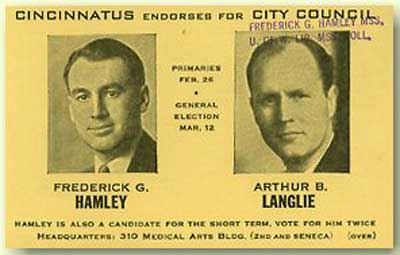

The New Order of Cincinnatus, a conservative anti-corruption and pseudo-fascist political organization elected its candidates to Seattle's City Council in the 1930s, on a vague platform of non-partisan conservativism. The Order was exclusively for young men, and its memberrs styled themselves after both militaristic and secret fraternal societies. Here is an endorsement flyer for Frederick G. Hamley and Arthur B. Langlie for Seattle City Council, 1935. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections, Frederick G. Hamley Papers, UW22336z

Discussions of politics during the Great Depression often focus on the progressive, left-wing—on assessments of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, Communists, and trade unions. Yet it is important to remember that the tenor of 1920s electoral politics nationwide were conservative, and Washington State—Republican-controlled until 1932—further contained a strong band of conservative Democrats.[1] Though blame for the Depression and inaction to solve it caused the Republican Party to practically collapse in 1932, and brought significant popular support for Roosevelt’s Democratic reformism, conservative political attitudes did not disappear in the 1930s. Instead, in the political realignments which followed the 1932 elections, some conservative Republicans and Democrats began to develop and join new movements which might better represent their views. This essay is a case study of one such non-partisan group based in the Northwest, which in the middle of the 1930s found considerable support.

The organization was created in 1933 by six young men disaffected by the Republican Party but unwilling to defect to the Democrats, and called itself the “New Order of Cincinnatus.”[2] A “youth movement” based in Seattle, Washington, it initially only accepted members between the ages of 21 and 35, and swore an idealistic commitment to clean, efficient government.[3] Fiscally conservative, the Order pledged to lower taxes and reduce local government expenditures, and to reduce waste by eliminating selfish politicians and graft.[4] The name was inspired by the Roman leader and farmer Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus, who in a time of war accepted power to serve the needs of his country, yet relinquished it once his duty was completed.[5] They saw themselves as virtuous citizens instead of career politicians, pledging instead to follow a selfless course to promote the public good.

The New Order of Cincinnatus expressed a not uncommon disillusionment with both the major political parties in certain areas of Washington State, as well as a serious apprehension about the growing influences of radical, labor, and vested interests in local and national politics. Cincinnatus had early electoral success with a very vague political platform of clean government and fiscal conservatism. This success indicated many people’s ambivalence toward the established political parties well into the 1930s, and implies that the New Deal, in Washington at least, was far from universally supported. The Cincinnatus movement suggests an underlying anxiety about some of the political and cultural changes in the 1930s, which manifested in all areas of the political spectrum. Cincinnatus, if not numerically strong, remained active, vocal, and vibrant until the late 1930s. Some of its members and the support they received fed back into the Republican Party toward the end of the decade, helping to elect a former member as governor of Washington State, and helping rebuild and reorganize a somewhat more conservative Republican Party that rebounded nationally and locally in the 1938 elections.

This paper presents the New Order of Cincinnatus’s short-lived experience in Seattle’s municipal political scene from 1933-1938, utilizing both archival documents from the organizations and its members and local newspaper coverage. By investigating the values and policies of the organization, the basis of its support, and in analyzing validity of the criticisms it received during election campaigns, I intend to show the continuing significance of conservatism during the Depression, despite its political weakness. These sources reveal the hostility, mistrust, and polarization that exemplified city politics at this time, especially during the run up to elections, and the negative effect this had on the ability of politicians and interested parties to develop stable political platforms and governments in a tumultuous environment. Nevertheless, the ability of “non-partisan” conservatism to develop successful and experienced politicians was crucial for the reconstruction of the Republican Party in the late 1930s both locally and nationwide.

The New Order of Cincinnatus’s first movements into the local political scene came in October 1933 when it took action to advocate for a better budget for King County, which was expected to have a large shortfall. The Order, under the leadership of M.C. McCoy, wrote a letter to the City Council “demanding that it balance its budget,” or, as the Seattle Times reported it, they warned, “the public would take reprisals.”[6] Later that month they would gain further publicity when they demanded that the County Commissioner should be removed from his office on the grounds, amongst other claimed abuses, that he was wanted in New York for stock fraud.[7] They were unsuccessful, but the publicity that came from their foray onto the political scene encouraged the group. In 1933, the Order had only a minor impact due to the infancy of their campaigns. Still, in January, 1934 they decided to support their own selection of candidates for the upcoming City Council elections.[8] Seattle municipal elections included the Mayoral and City Council offices, and held non-partisan elections since 1910 following an amendment to the City charter. Since no party affiliation was to appear on the ballot, the fiscal conservatism of Cincinnatus could be presented outside the discredited politics of the Republican Party, and could allow Cincinnatus to receive a large degree of Democratic Party voters.

Opponents argued that Cincinnatus members subverted the spirit of the system by running as a third party under the pretense of non-partisanship. Critics’ objections were understandable, considering, for example, that Cincinnatus members registered candidates for the election as a “slate” in order to be visible on the ballot paper, with all candidates’ middle names listed as “Cincinnatus.” Furthermore, the group organized for members to be posted at polling stations around the clock, and requiring that all wear their green cap uniform to canvass support.[9] Regardless, and despite their comparatively unknown status, they did receive some positive newspaper coverage in the major dailies, particularly in the Seattle Daily Times. The Times praised the group for what itcalled a “novel idea,” the policy of making available on demand an “inventory of their personal possessions” to discourage political corruption.[10]

In addition to running slates of candidates for office while claiming to be non-partisan, Cincinnatus developed a distinct economic policy despite its stated desire to produce independent candidates. The Order’s promotional pamphlet from 1934, “What is Cincinnatus?”unabashedly asserted that, in the depths of the Depression, Cincinnatus “admits frankly that it does not know the answer to all our problems.”[11] They acknowledged that they had “no economic theories” to “cure” to the Depression, as there was no quick fix. Since one of their goals was to produce politicians “free from obligations to anyone” or any political creed, their vague election propaganda could also be intended to counteract the development of a dominant political theory that all Order political candidates would be bound by. Even as late as 1936, the pinnacle of Cincinnatus’s success, Frederick Hamley was reluctant to state the definite goals of the group for fear of “confining the organization to them.” He further stated in a memo that, three years into the group’s history, “we have not yet reached the point where we can state definitely just what are the complete and ultimate objectives, [of The New Order of Cincinnatus] other than to do those things which would improve local government.”[12] Despite these disavowals of a comprehensive fiscal policy, they adhered to a particular version of enlightened American liberalism when they posed the question, “who is going to solve these riddles? Men skilled in business, in agriculture, scientists and practical executives, or cheap politicians?” Pragmatic politics to Cincinnatus meant limiting the waste of public money by governments, and letting experts solve the bigger problems. They did, therefore, have economic initiatives but limited their scope to the local and regional. Cincinnatus focused on creating balanced budgets and lowering taxation. Welfare and regulation, if necessary, was deemed the responsibility and initiative of the national and state governments.

Another part of the art of the success of the Order was its different and honest appeal, which resonated with some voters disappointed by political hype. The Order attacked politicians as ineffectual careerists who could not solve the economic problems of the Depression, and the Order suggested those who proclaimed they did have the answers were “fools or worse, hypocrites.” The pamphlet continued to argue that Cincinnatus’s honesty “must be reassuring to a patient who has listened to ‘quacks’ offering him every relief possible to the imagination, and delivering him nothing but more taxes and political chicanery.”[13]

Cincinnatus’s skepticism about the federal government’s ability to solve the unemployment crisis offered direct criticism of most emerging political thought at the time. Their rhetoric complained that “the ‘gimmie’ spirit that has swept America” and criticized, without actually identifying them, New Dealers, who made “deceitful promises of ‘something for nothing.’”[14] Though the pamphlet did accept that some form of relief was unavoidable in that “the hungry must be fed,” it argued that “greed must be eliminated from the administration of relief funds.” It may have been acceptable for them to largely ignore relief policies because they were administered more by national and county divisions largely independent of the City Council’s responsibility. But it also reveals the resentment that some people felt toward the vast amount of government spending the New Deal involved. The Order of Cincinnatus instead favored tax cuts which they claimed would limit inefficiency and graft in government by “at least forty percent” of the 1933 values.[15] Aside from this, Cincinnatus promised little except to deliver politicians “with enough courage” to “tell the people not what they want to hear, but what they ought to hear pleasant or otherwise.”[16]

Cincinnatus did not just indirectly criticize the New Deal. It also regularly denounced all forms of radical politics, reducing their appeal to “the danger that hungry men and women will seize upon most anything in their desperation.”[17] Historian George William Scott argues that the Order of Cincinnatus members believed they were involved in a “middle-of-the-road campaign” and shunned both radicals and “extreme conservatives.”[18] Ralph Potts, a founding member and Commander of the group also claimed it was a movement “conservative in principle, but radical in method,” and that many members would have actually embraced radicalism “if they could see there any hope.”[19] Yet regardless of the political self-identification of its leaders, much of the rhetoric of the Order at this time, as demonstrated in Cincinnatus promotional pamphlets and literature, had a patently conservative and anti-radical tone. According to one political pamphlet,

“There must be no destruction. No bloodshed. No dictatorship of a class or individual. There must be no loss of liberty. The changes, if they come economically, must be orderly and well considered, they must be made by sincere and capable men who seek to alter, improve and build for the benefit of all rather than giving our country over to the unfit to destroy for the benefit of the few.”[20]

That changes would be “for the benefit of a few,” was clearly the greatest which Cincinnatus members and sympathizers could concede towards the radicals, presumably because Cincinnatus members were not drawn from the class who would benefit. The small selection of membership applications that exists in archives for the Tacoma branch of the organization cannot provide a comprehensive analysis of the entire membership base, but it does suggest that types of people drawn to the ideals of the New Order of Cincinnatus. Members’ occupations included managers, salesmen, secretaries, lumbermen, a mechanical engineer, and lawyers.[21] Assessing the backgrounds of the founders and leaders can also facilitate a better understanding of their motives and support base. Most of the leadership were professionals. Potts, for example, was a lawyer. David Lockwood, elected to the city council in 1935, was an accountant. Lockwood’s colleagues, Lloyd Johnson and Wellington Rhinehart, who were not so successful in electoral politics, were an “insurance man” and a chemical engineer respectively.[22] This evidence supports the conclusion that much of the membership support came from young middle-class men, who because of the circumstances of the Depression had found themselves “involuntarily stagnated at the end of their studies.”[23]

But the membership was always a limited representation of Cincinnatus’s popular support, not least because it was restricted to men under the age of 35 of “good standing.” Cincinnatus did recognize the need to appeal to the wider electorate. In a pamphlet from 1934 entitled “CINCINNATUS – and why has it entered this campaign?,” the focus of the argument is directed toward older male voters. It urges them to persuade “Your son, if he has imagination and intelligence” to join the Order while suggesting they become “Associates,” the Order’s auxiliary for men over 35.[24] In the city council election of 1935, the highest Cincinnatus candidate Arthur Langlie polled 49,278 votes. Similarly, in 1934 David Lockwood earned 62,179. Both were elected.[25] These victories suggest that Cincinnatus rhetoric appealed to a much wider audience than their membership alone.

Yet if its manifesto remained deliberately elusive, behind the scenes the Cincinnatus hierarchy was laying much of the foundation for their future plan to clean up Seattle. In 1933, Albert A. King, the Cincinnatus treasurer, recognized that the organization could not hope to retain supporters through empty words alone, and drafted new guidelines Cincinnatus members. The proposed plan outlined several changes that would become important to the Order’s future functioning, with proposed divisions in charge of admissions, communications, investigations, membership promotion, speeches, programs, campaigns, governmental reorganization, and extensions.[26] Of these, the proposed “Investigations division” was the most interesting, charged with obtaining “facts” and examples of corruption, because “general charges of graft are little more than mud-slinging when there is no proof of to back them up.”[27] King was “sure that there are many members of Cincinnatus who “would get a genuine kick out of some real detective work.”[28]

In 1934, Cincinnatus managed, somewhat unexpectedly, to gain a reputation as a significant party when their candidate for City Council, David Lockwood, won the general council election, despite only just making it through the primaries in sixth place.[29] However, the New Order of Cincinnatus’s real impact on Seattle politics would not come until 1935, when two more candidates—Arthur B. Langlie and Frederick G. Hamley—would be elected, alongside independent veteran of the school board Mrs. F.F. Powell. Together with Lockwood, they were able to create a strong voting force within the City Council. The Cincinnatus candidates in 1935 ran on the popularity of Lockwood, who took his electoral mandate to uncover corruption in the police forces and city government.

Arthur Langlie, who had run for Seattle City Council under the New Order of Cincinnatus, transitioned from the Order to the Republican Party and was elected as Seattle's Mayor in 1938. Langlie is shown here, in 1949, when he had advanced to the office of State Governor. Despite the unpopularity of conservatism in the 1930s, the New Order of Cincinnatus helped nurture politicians who would become key players in state conservative politics in the 1940s. Click image to enlarge. (Courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry)

The election of Cincinnatus candidates brought fierce counter-attacks. Though Lockwood won by a large majority over incumbents Levine, Fitts, and Gaines, his election campaign was tarnished with the animosity of opposing groups of candidates. One of the most notorious and most persistent attacks made by the Cincinnatus opposition was an accusation of the Order’s supposed links to and similarities with fascism, then on the rise in Europe. In the run up to the 1935 City Council elections, opponents highlighted the Order’s militaristic style and restrictive membership. The argument that Cincinnatus had a paramilitary quality came from its aggressive investigation tactics in policing the government and the political and military regimentation of the organization, especially apparent in the titles it designated to its leadership. The Cincinnatus leader was called the “Commander,” and junior officials who constituted the “officers’ council” were designated with ranks of “Captain” and above.[30] Order members also occasionally wore uniforms that included white shirts and green caps with a yellow stripe, which Potts claimed were modeled after those of the American Legion veterans’ association.[31] In the early years of the organization, the group participated in uniformed marches and sang their “fighting song” to the tune of Sigmund Romberg’s “Stout-hearted Men.”[32]

This formation was hardly as radical or militaristic as it seemed on the surface, however. Indeed, in 1933 this style did not seem as threatening as it would later become when European fascism was more widely known; indeed, the Order’s style led to more comparisons with “boy scouts” than soldiers. Furthermore, this period of the organization was short-lived, and the Order soon gained a more respectable political image. However, it is possible that Potts may have intended to move the organization in the direction of fascism. Scott’s history claims that the “exact nature of his intent was unclear,” but argues that Potts’s strong executive powers and desire for a national unification of youth movements led to his forced resignation after the electoral defeats in 1933.[33] By 1934, the Cincinnatus constitution had been changed, and the Commander was now explicitly subject to election by the membership with a maximum limit of two terms. This elected official could be “deposed” upon a majority vote. The Officer’s Council became the organization’s legislative authority, consisting of permanent officers and a representative of each district. In essence, disregarding the semantics, the Order claimed to borrow much of its structure from the United States Constitution, complete with a “Cincinnatus Court.”[34] Furthermore, the Order was overt in its attempts to provide a distinctly American solution to the pervading crisis of Depression, “saving democracy” and shunning both fascism and communism as undesirable “European ‘isms.”[35]

Exclusive membership policies also received heavy criticism from Cincinnatus opponents. In a half page advertisement entitled “Secret Hands must not rule Seattle,” which was originally published as an editorial in the Labor News, Clay Nixon, who claimed to be a former Vice-Commander of the New Order of Cincinnatus, made the defamatory accusation that Cincinnatus had “a policy of exclusion of all Jews and persons not native born.”[36] Yet there is no evidence that this was the case. The Cincinnatus Constitution did limit membership to American citizens, but made no reference, in print at least, that they must be born in the United States.[37] It is possible that there was an unwritten policy of exclusion of certain religious groups, but opponents’ condemnations may have been tinged with a desire to draw votes from their competitors by playing on fears of fascism. When John Dore, a Catholic, ran for Mayor in 1936, he also alluded to accusations of religious discrimination by Cincinnatus, comparing them to the Ku Klux Klan and Know-Nothing movements.[38] Cincinnatus, which was composed of predominantly Protestant members, may have seemed a valid threat to both Dore’s career aspirations and his religion.[39]

Opponents’ charge that the Order was contrary to the principles of democracy because it barred all women and men over the age of 35 was entirely accurate. The selective membership policies of the Order allowed opponents to accurately describe them as a “secret organization” and therefore undemocratic. Yet this criticism overlooks the comparable policies of other secret fraternal organizations at the time, and in this light, the Orders’ secrecy, grand titles, and all-male policies do not appear quite as strange. In fact, according to the Tacoma membership applications, some of the members of Cincinnatus were also members of fraternal order of the Masons, and Cincinnatus often used the Mason’s Hall as a meeting space. Furthermore, the Seattle Times mentions in the run up to the 1938 election that Arthur Langlie was the president the Seattle lodge of the Scandinavian Fraternity of America for the previous two years with very little concern.[40] Participation in fraternal organizations was clearly not unusual for members of the New Order of Cincinnatus, yet any influential connection is difficult to make on the evidence. Whether it was opponents’ genuine concerns about democracy or more tactical political move, the candidates Langlie and Hamley were reduced in the press to “beguiled puppets” of “hidden hands.”[41]

However, Cincinnatus trafficked in similar accusations, and did not occupy the moral high ground in campaign politicking. Several weeks before the election, the Order issued advertisements similar to this one in the Seattle Daily Times which urged voters to “oust the political barnacles,” claiming that the current occupants of the City Council, with the exception of Lockwood of course, were “entrenched, Tax-Hungry Politicians.” The Seattle Daily Times also reported that Cincinnatus candidates and supporters “In all [campaign] talks… directed their attacks against the incumbent councilmen.”[42]

In all, this seems to demonstrate a fairly underhanded and aggressive political culture of campaigning that existed during the Depression. Contrary to stereotypes of the era as one in which voters and politicians split purely over ideology, candidates for Seattle City Council sought to undermine their opponents’ credibility rather than to promoting their own policy proposals. In fact, in the entire anti-Cincinnatus “Secret Hands” editorial, only a tiny strip at the bottom of the page reading “Vote for Levine, Fitts, Gaines” makes any allusion to the political source of the criticism.[43] In the “Secret Hands Rule Seattle” article the editor comments, rather hypocritically, that “character assassination is the readiest tool in a ruthless drive for power.” If this was the case, almost all candidates were guilty of it.[44]

Cincinnatus’s dominance in Seattle’s City Council after the election of Langlie and Hamley allowed the group to push several aspects of their budget-cutting agenda. One of the most successful of these was the establishment of a centralized purchasing system to increase efficiency and reduce the cost of government in Seattle, which was approved as a charter amendment in March 1936.[45] Lockwood was recognized with an award presented to him by the United States Junior Chamber of Commerce for his “outstanding” work in facilitating the plan, and it was widely supported.[46] However other Cincinnatus measures received a more mixed response. One of the most controversial of these was the repeated proposal by Cincinnatus to reduce the annual budget by cutting public sector jobs. This had begun as early as 1934 when Lockwood secured the reduction of the City Council from a group of nine to six. In 1935-6, Cincinnatus targeted the police and fire departments, reasoning that “well equipped” and “educated men” were better than “mere numbers.”[47] They further eliminated the “soft jobs” done by police and firefighters, such as clerical work and maintenance, by detailing firefighters to do them in their non-active time, and replacing police officers with lower-paid civilian clerks.[48]

Cincinnatus reasoned that in 1937, when their budget of $10,420,000 was faced with a deficit of $2,800,000, their job was to cut costs at the least possible impact to actual service.[49] However, one critic who voted for the organizations in the 1935 election wrote a letter a few months later complaining that the council members were “do-or-die budget-cutters slashing expenses with no regard for the welfare of the public,” arguing that there were some public services that had to be supported “at all cost.”[50] In the same publication “A. Citizen” argued that Cincinnatus’s campaign “platform of more efficient government services” promised “better government services,” but that Cincinnatus members, once elected, only sought to lower taxes for the rich “at the expense of the general public.” In 1937, though they had resisted the cutting of firefighters, Cincinnatus tried unsuccessfully to axe two battalion chiefs rather than vote to increase taxes like their fellow councilman Scavotto wanted.[51] Order members’ strict adherence to budget-cutting and the elimination of public sector jobs constituted part of the reason for voters’ rejection of Cincinnatus incumbents’ reelection in 1937.

Seattle politics in the Depression, rather than reflecting a simple shift from one party to another, mainly reflected a decade of anti-incumbent sentiment by voters. Between 1929 and 1938, only nine incumbents managed to retain their positions whereas eighteen new council members were elected.[52] One political scientist analyzing this data argued that the unstable socioeconomic circumstances that characterized the Depression persuaded people to express their insecurity by voting for “change,” even if that meant ousting candidates that had only been elected a single term prior.[53] One journalist reporting on the 1934 election campaign summed up this opinion when he responded to the accusation that Lockwood, the 1934 Cincinnatus councilman, had “tried to block every constructive bit of work the Council has done,” by retorting “Here we have to await more specific information. Just what constructive bit of work has the Council done in the past year?” This desire for change seems apparent in the lack of support for Cincinnatus in the elections of 1936-7, where none of the three incumbents retained their offices. The next two years would be similarly plagued by malicious campaign rhetoric, though characterized more by the manipulation and promises of political favors, especially with the connections between Mayor Dore and local labor leader Dave Beck.

The Teamsters Union, under the strong leadership of Dave Beck, was one of the most powerful voting blocs in municipal elections, since the loyalty of union members would make them likely to accept the candidate their leadership endorsed. In the 1936 City Council elections, Teamster bosses distributed letters to their membership explaining that certain candidates were “recommended to you because your union feels that they will best serve your interests.”[54] Cincinnatus disapproved of candidate endorsements by specific groups since they believed it could contribute to corruption by creating a vested interest for the politician. John Dore was an opportunistic politician who altered his views radically to appeal to the voters. Before receiving Beck’s support he had attempted to persuade both the “liberal” and business interests to his cause.[55] Following his election in 1936, Dore stated that, “Brother Dave Beck was the greatest factor in my election and I am going to pay back my debt to him and the teamsters in the next two years regardless of what happens,” a statement which Cincinnatus would use in attempting to mobilize opposition the following year.[56] Though Beck was pro-business, anti-radical, and opposed to rank-and-file democracy in his labor politics, the heavy-handed tactics of his union were often criticized and Dore received significant disfavor from several quarters who accused him of “racketeering labor.”[57] A split in the labor vote between the American Federation of Labor and the Teamsters Union compounded with the anti-labor sentiment created by Beck and guaranteed Langlie’s election to Mayor in 1938.[58]

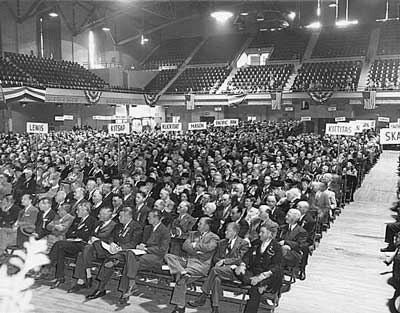

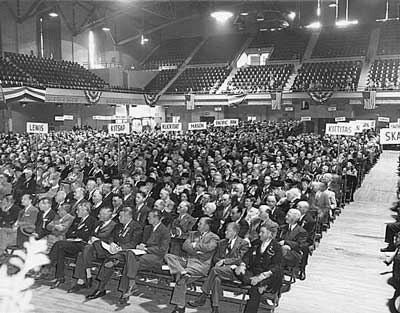

Washington State's Republican Party Convention, 1946. Members of the New Order of Cincinnatus transitioned into the Republicans as Cincinnatus dies out in 1937-1938, in order to forge a more mainstream conservative opposition to Roosevelt's labor-left New Deal Democratic coalition. Click image to enlarge. (Courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry)

How had Cincinnatus succeeded in electing one of their members as Mayor? The answer lies in the simultaneous decline of the Order’s influence and Order member’s embrace of the Republican Party. In the wake of defeat in the Mayoral and City Council elections of 1936, Cincinnatus members had sought to remodel their movement and remove its most controversial aspects. There seemed to be some consensus by the remaining Order elites that the remnants of the earlier pseudo-fascist and secretive style that had brought attention in 1933 were no longer necessary or beneficial to their cause. Besides, these had mainly been on the initiative of Ralph Potts, who was not a prominent member of the Order at this point. In a letter dated April 3, 1936, City Councilman Frederick Hamley recommended revisions designed to combat “the misconstruction of political opponents who pretend to find it an indication of fascism.”[59] Primarily, as discussed above, the necessary changes were enacted in the wording of Cincinnatus organizational documents and promotional literature. The term “Commander” was to be replaced by “executive officer” on all occasions, “grand lodge” was also to be eliminated for its association with secret societies, and it was “put permanently on record, so that any assertion to the contrary can be proven untrue,” that “membership cannot be limited by race creed etc.”[60]

These changes were largely cosmetic. Even Commander Potts as early as November 27, 1934 had questioned the organization of the Order. In a letter to Captain Charles Sully Potts asked for an opinion on whether the New Order of Cincinnatus should adopt more egalitarian and democratic policies.[61] He considered the benefits and disadvantages of popular elections for Captains versus nomination and appointment by the Commander. He further wondered whether the limits should be lifted to include women and men of all ages or to “hold the maximum between 35 and 40 years and maintain our individuality and identity as a young men’s movement?” In this sense the changes that were enacted in 1936 only confirmed the direction and values of the Order while avoiding a more inclusive membership policy.

Adaptability within politics was essential during the Depression, yet so was the ability to realize when something had failed and to move on. By the end of 1937, Cincinnatus had lost most of its influence in city politics and was plagued by factions and disagreements between old and new members over its future direction.[62] Its novelty had worn off, and its council members had lost reelection against a powerful labor coalition. Order member’s acceptance of the Republican Party would not be confirmed, however, until 1940 when Langlie accepted the offer to run for governor on their ticket and won. When Arthur Langlie managed to run successfully for Seattle Mayor in 1938, it was as a Republican, not a Cincinnatian.[63] When Cincinnatus lost momentum in 1937, it was because of an increasing public indifference toward the movement. But as one historian suggests, its young founders had gotten older and “the talented of the leadership graduat[ed] to partisanship.”[64] In a way this seems very accurate: with the Depression ending and Cincinnatus’s earlier urgency fading, Lockwood and Hamley followed Langlie to Olympia and served as Director of the Washington Department of Public Services and State Budget director respectively.

With the Depression improving, a renewal of Republican popularity was possible and conservative politicians, like those in the Order of Cincinnatus, used their political experiences of the 1930s to transition into the emerging Republican Party and help shape its conservative politics.

The New Order of Cincinnatus developed a locally based third party in Seattle in the 1930s, experiencing an incredibly mixed response of support and ridicule from the people of Seattle. Cincinnatus played to mainly middle-class voters who were disillusioned with the Republican Party for their corruption and mismanagement of the Depression, but resentful of the New Deal Democratic Party’s high spending, expansion of social welfare, and taxation. Their opponents sought to discredit the order with accusations of fascism, secrecy, and un-democratic exclusionary policies, sometimes misrepresenting the Order. This turbulent environment created an extremely difficult situation for any stable political movement to develop, and the New Order of Cincinnatus, like many other new groups created in the 1930s could not survive long.

In the 1938 Mayoral election, Langlie was aided by the failures of labor and the developing illness of John Dore, but he also benefitted from a surge of conservative and republican sentiments that were developing nationally by 1938 and continued through the end of the Second World War. While President Roosevelt personally remained popular, his party lost 70 seats in the House of Representatives in 1938, and by 1942, Democrat’s congressional majority had been reduced from 242 in 1936 to just 10.[65] The failure of the New Order of Cincinnatus coincided with the revival of the Republican Party in electoral politics in the late 1930s, which in turn was helped by a growing disillusionment with the New Deal programs.[66] An article in the Seattle Times describes the role of the blanket (non-partisan) primary and the role of conservative Democratic revolt in promoting Republican victories in the state, including that of Langlie, over their New Deal rivals.[67] Both Republican and conservative Democratic support was crucial for the revival of Republican electoral success both locally and nationally, which demonstrates the role played by parties such as Cincinnatus. Non-partisan conservative support remained active and gained political experience during the Depression years, despite a lack of widespread public support, which positioned them to help mold a reinvigorated Republican Party when public sentiments shifted.

Copyright (c) 2010, Emma LunecHSTAA 498, Winter 2010

[1] Richard Berner,

Seattle in the 20th Century: Vol. 2 Seattle, 1921-1940 From Boom to Bust, (Seattle, Wash : Charles Press), 326.

[2] George William Scott, “The New Order of Cincinnatus,” (MA Thesis., University of Washington, 1966), 1.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ralph Bushnell Potts papers, “What is Cincinnatus?” Folder 1, Box 2, Accession # 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[5] Scott, “The New Order of Cincinnatus,” 1.

[6] “County heads summoned for budget slashing”

Seattle Daily Times, October 2

1933, page

10.

[7] Scott, “New Order of Cincinnatus,” 11.

[8] “3 Cincinnatus members to run for city council,”

Seattle Daily Times, January 21 1934.

[9] “Untitled memo on election plans” Potts papers, Box 2, Accession # 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[10] “3 Cincinnatus members to run for city council,”

Seattle Daily Times, January 21 1934.

[11] Potts papers, “What is Cincinnatus?”

[12] Frederick Hamley, “Memo to Herbert Metke” Potts papers, Folder 3, Box 2, Accession # 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[13] Potts papers, “What is Cincinnatus?”

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Scott, “New Order of Cincinnatus,” 47.

[19] Scott, “New Order of Cincinnatus,” 6.

[20] Potts papers, “What is Cincinnatus?”

[21] Russell O. Vognild Papers, “collected membership applications” Accession # 0482-001, University of Washington Special Collections.

[22] Scott, “New Order of Cincinnatus,” 267.

[23] Scott, “New Order of Cincinnatus,” 6.

[24] Ralph Bushnell Potts papers, “CINCINNATUS- and why has it entered this campaign?” Folder 1, Box 2, Accession 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[25] Gordon Charles McKibben, “Nonpartisan politics: a case study of Seattle” (MA Thesis, University of Washington, 1954

) 38.

[26] Albert A. King, “Proposed Plan of Organization for the New Order of Cincinnatus,” Albert A King papers, Accession # 0473-002, University of Washington.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] McKibben, “Nonpartisan politics,” 38.

[30] Scott, “The New Order of Cincinnatus,” 239.

[31] Ralph Potts, Seattle heritage (Seattle, 1955) 121.

[32] Scott, “The New Order of Cincinnatus,” 27.

[33] Scott, “The New Order of Cincinnatus,” 52-54.

[34] Ralph Bushnell Potts papers, “Cincinnatus Constitution” 1934, Folder 1, Box 2, Accession 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[35] Potts papers, “What is Cincinnatus?”

[36] “Secret hands must not rule Seattle.”

[37] Potts, “Cincinnatus constitution 1934.”

[38] Dore election letter, Ralph Bushnell Potts papers Box 2, Accession 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[39] “Candidates for Mayor”

Seattle Times February 20 1938.

[40] Seattle Daily Times February 14 1938, page 7.

[41] “Secret hands must not rule Seattle.”

[42] Seattle Daily Times May 3 1935, page 3.

[43] “Secret hands must not rule Seattle.”

[44] Ibid.

[45] “Cincinnatus Record in office 1936,” Ralph Bushnell Potts Papers Box 2 Folder 7, Accession 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[46] City Budget cuts will total $200,000 Seattle times January 23 1937 Page 2.

[47] “A program for good government,” 1935.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Cincinnatus 1937 budget proposal, Potts papers, Box 2, Folder 7, Accession 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[50] A.J. Letter to editor of

Cincinnatus Weekly July 6 1935, Box 2, Folder 11, Accession 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[51] City Budget cuts will total $200,000 Seattle times January 23 1937 Page 2.

[52] McKibben, “Nonpartisan politics,” 5.

[53] McKibben, “Nonpartisan politics,” 55.

[54] “Teamsters letter for support” Box 2, Accession 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[55] Berner,

Seattle in the 20th Century, vol. 2, 379.

[56] Letter, March 3 1937, Potts papers.

[57] Berner,

Seattle in the 20th Century, vol. 2,400.

[58] Berner,

Seattle in the 20th Century, vol. 2,401.

[59] Frederick G Hamley “letter to Herbert Metke,” Box 2, Accession 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ralph Potts, “letter to Charles Sully,” Nov 27 1934 Box 2, Accession 0932-003, University of Washington Special Collections.

[62] Scott, “The New Order of Cincinnatus,” 2.

[63] Scott, “The New Order of Cincinnatus,” 231.

[64] Scott, “The New Order of Cincinnatus,” 233.

[65] Alan Brinkley,

The End of Reform (New York, 1995), 139.

[66] Ibid.

[67] J.W. Gilbert, “Open Primary to hit Leftists”

Seattle Daily Times March 3, 1938.