by Andrew Knudsen

University of Washington teaching assistant and Local 401 member Hugh DeLacy was fired by UW President Sieg when he ran for a seat on Seattle's City Council. DeLacy won that election and later was elected to Congress. (Sunday News, August 1, 1936).The story of University of Washington Local 401 of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) spans the Great Depression to the Cold War. On campus, the Local earned a reputation as a bastion of radical politics and social activism. The union not only helped faculty members with their own professional concerns but also gave them a connection to organized labor and a forum to express their liberal political views on global issues.

AFT Local 401 began its life in a flurry of activity and met its end in a similarly dramatic fashion. Its demise is largely attributed to its apparent and at times conspicuous adherence to Communist Party dogma before and during World War II. These and other leftist activities led to the most significant event in the history of Local 401, the Canwell investigation of 1948, during which several University of Washington instructors were subpoenaed to appear before a House Un-American Activities Committee and faced charges of membership in the Communist Party. After the Canwell sessions, six of the subpoenaed professors were made to stand before the University of Washington’s own Committee on Tenure and Academic Freedom.

Ultimately the University decided to dismiss three of the six professors and placed the remainder on probation. All the professors made to appear before the Canwell Committee were members of AFT Local 401. Almost immediately after the hearings, the AFT national office moved to revoke is charter.

The story of Local 401, then, is an examination of how these members used their AFT Local to advance their professional and political interests and the varying success with which their Local defended those interests. It is also a window into radical politics on campus and in the city of Seattle through the Depression, World War II, and the Cold War.

American Federation of Teachers

In its October 1947 issue, the AFT's Washington State Teacher explored the meaning of freedom. A few months later the Canwell Committee launched its investigation of suspected Communists on the faculty of the University of Washington. Just one year later, the AFT disolved Local 401. Click picture to learn more about the AFT's Washington State TeacherEstablished in April of 1916 in Chicago, the American Federation of Teachers became the first teachers union to affiliate with organized labor, joining with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in May of that same year. The AFT survived its first few difficult years and managed to spread its influence throughout urban centers in the Midwest and East Coast. The AFT attracted new locals largely because it spoke to the needs of the classroom teacher, and its affiliation with organized labor made it an attractive organization to those with socially progressive views.

Though directed primarily toward improving conditions for the classroom teacher, the AFT made bids to organize college locals. These were largely unsuccessful until the 1930s, when the Depression worsened conditions on college campuses, causing many teachers to lose their jobs without adequate explanation or avenues for recourse. During the Depression, the AFT came to be recognized among educators as a more assertive and dynamic organization than its more traditional counterparts, the National Education Association (NEA) and the American Association of University Professors (AAUP). The AFT also championed numerous progressive causes in both education and civil rights, earning a strong reputation in liberal quarters and condemnation from conservative elements.1 The experiences of the AFT local on the University of Washington campus between the years of 1935 and 1948 were no exception.

University of Washington

At the University of Washington in May of 1935, College Local 401 of the American Federation of Teachers was established. According to one member of the Local, the response of instructors to affiliating with the AFT was “immediate and enthusiastic,” as it provided an outlet not only for discussions related to professional politics but also ones of wider significance.2 At the forefront of these member’s political consciousness was an opposition to fascism and support for organized labor, two causes very popular with university faculty during the mid to late thirties.3 Although some estimates have put union membership at around one hundred at its inception,4 a closer look at the financial records of Local 401 show that the number of members who were active and paying dues hovered between twenty and thirty. In 1943, the Local numbered around forty-seven, fourteen of whom were original members. By 1947, the Local was composed of around sixty-five members with roughly the same amount of founding members staying on.5

During the Local’s lifespan from 1935 to 1948, the Local’s size fluctuated as it constantly added new members and lost old ones. Throughout the many comings and goings, however, a core of dedicated charter members stayed with the Local until its expulsion from the AFT in October of 1948. Like most of its members throughout 401’s thirteen-year history, these instructors came from backgrounds in the humanities and social sciences. The majority taught in the Psychology, Sociology, Philosophy, English, and History departments. Each of the six members put on trial by the Canwell Committee and the Faculty Committee on Tenure in 1948 had been active in the union since 1935 and their backgrounds were representative of the rank and file. Ralph Gundlach came from the Psychology Department; Herbert J. Phillips from the Philosophy Department; E. Harold Eby, Garland Ethel, and James Butterworth from the English Department; and Melville Jacobs from the Anthropology Department. 6

Like many other college locals that joined the AFT during the lean Depression years, it was the union’s active role in progressive causes and affiliation with labor that attracted most to join. Although the aims of college locals varied widely, common concerns were uniform salary scales, systems for the preservation of tenure, channels for dismissal appeals, and a defense of academic freedom.7 In their approach to pursuing these fundamental objectives, Local 401 showed itself to be a dutiful member of the AFT and its new state-level organization, the Washington State Federation of Teachers (WSFT). Discussions of tenure and salary issues were frequent at 401 meetings as was the defense of unfair dismissals.8

One such instance of Local 401’s action against unfair dismissal was the Thayer case in 1946. An instructor in the History Department, Robert Thayer had been promised full professorship and tenure by his department only to have his position handed over to a newcomer whom the Dean preferred. Local 401 petitioned the department for further explanation and issued formal complaints to faculty. The issue finally faded after Thayer left the University of Washington to take a position at another school.9

In confronting issues such as tenure, members of Local 401 also sought the allegiance of other campus organizations such as the University of Washington chapter of the AAUP.10 Members of 401 were active in drawing up petitions and resolutions and kept their secretary busy sending out communications to government and university officials.11 In addition, the officers of the executive board were consistent participators at WSFT annual meetings.12

The Local was both an avenue for protecting its member’s professional interests and an outlet for the advancement of their wider social concerns. With a membership composed of many socially and politically conscious individuals, it is not surprising that members of Local 401 took part in political organizations outside the union. One of the most important of these was the Washington Commonwealth Federation.

Washington Commonwealth Federation

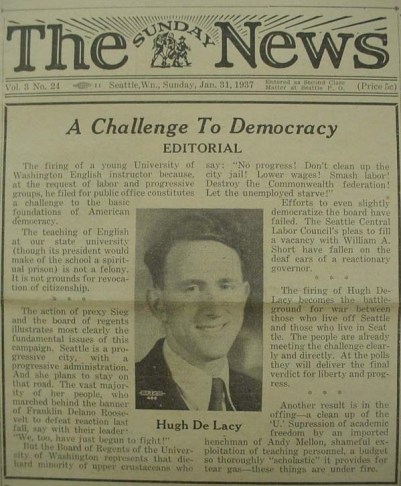

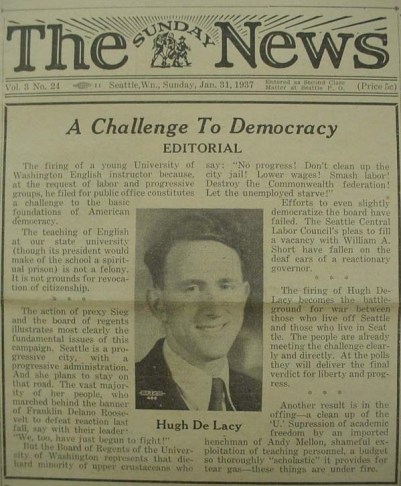

In this front page editorial, the Washingon Commonwealth newspaper blasted the UW Board of Regents as a "die-hard minority of uppercrusters" for firing Hugh DeLacy (Sunday News, January 31, 1937).In many ways, the birth of Local 401 was tied to the development of the Washington Commonwealth Federation (WCF) during the Great Depression. Many of the key figures involved in the creation of the WCF were also instrumental in establishing Local 401. The WCF’s role as a radical wing of Washington’s Democratic Party, an anti-fascist coalition, and a Communist Party Popular Front organization made it one of the most visible and controversial political organizations in Washington during the Depression.

Much of the controversy that surrounded the WCF had to do with its involvement in supposed Communist causes. Its role as a Popular Front organization that opposed fascism made it attractive to members of Washington’s Communist Party (CP). Many of these CP members eventually did work their way into the WCF and affected many of its policies and platforms despite the organization’s official opposition to the party.13

This is important to explaining the origins of Local 401, as many of the union’s founding members were either officers or active participants in the WCF and some were later confirmed members of the CP. Some of those involved in both the WCF and Local 401 were E. Harold Eby, Melvin Rader, Selden Menefee, and Hugh DeLacy.14 While some, like Rader, admitted to only limited participation in the WCF, others such as Eby served on the executive board for a number of years.15 Other notable participants included Selden Menefee, who contributed an article to The Nation on behalf of the WCF in which he analyzed the Seattle City Council elections of 1938. It was during these elections that another member of Local 401, Hugh DeLacy, stirred controversy by running for and earning a seat on the City Council.16

Perhaps one of the most high-profile figures in Seattle politics during the Depression, Hugh DeLacy had a strong background in both Local 401 and the WCF. DeLacy earned his Bachelor’s degree in English from the University of Washington in 1932 and later taught as a graduate assistant in the University’s English Department. In the English Department, he met faculty members whose social activism influenced his already liberal political views and led to him becoming one of 401’s charter members in 1935.17 Originally recruited into the union by Professor Eby of the English Department, DeLacy proved to be a very active member of the Local, serving as its delegate to the Seattle Central Labor Council18 and as regional vice-president on the AFT’s national Executive Council in 1937.19

DeLacy soon made waves on campus in 1936 by announcing his intent to run for Seattle City Council. This declaration prompted University President Lee Paul Sieg to dismiss DeLacy from the payroll for his violation of the Regent’s policy against instructors holding public office.20 Sieg’s action sparked a protest by students and prompted some labor publications to direct vehement attacks against Sieg.21 Amid this controversy, the WCF stepped in and put its support behind DeLacy’s eventually successful bid for City Council.

In The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front, historian Albert Acena argues that DeLacy’s membership in Local 401 and the controversy surrounding his dismissal were major reasons for the strong backing he received from the WCF during his campaign.22 DeLacy’s brief stint in the Marine Fireman’s Association also helped him earn support from other segments of organized labor that condemned Sieg’s action. According to DeLacy, the conservative Sieg and his fellow administrators reacted to the furor by harassing the membership of Local 401.23 While the reaction of 401 to the University President’s action is unclear, what is apparent is that situations like DeLacy’s showed Local 401’s willingness to court controversy. Only two years after its birth, members of Local 401 were in the thick of Seattle’s political culture and attracting criticism from University administrators. Only in its infancy, Local 401, “the most left-wing faculty organization on the campus,” was developing a reputation for ‘dangerous’ radicalism among University officials that would only worsen over time.24

Labor Solidarity

Local 401’s best days may have been during the Depression and the events leading up to World War II. It was during the New Deal era that the possibilities presented by the union must have seemed most promising, and while the prospects of turning the tide of local and world events seemed, if not easy, certainly well worth fighting for. In Melvin Rader’s book False Witness, the one-time president and prominent member of Local 401 detailed the colorful character of the New Deal era in Seattle and around the world. In describing the explosion of labor and radical leftist organizations in the city during the mid-thirties, Rader revealed that his membership in the newly formed teacher’s local was a major part of his involvement in Communist Party-sponsored United Front organizations. These organizations kept a close eye on European events and maintained a staunch opposition to fascism and totalitarianism. Besides belonging to the teacher’s union, Rader was a member of the WCF, which itself was comprised of several unions and cooperatives, including the Unemployed Citizens League.25

Though he participated in many different organizations it was his association with Local 401 that was his closest. In one story, Rader relates 401’s involvement in the September, 1936 strike against the Seattle Post-Intelligencer that received widespread support from several segments of organized labor. He tells of some of 401’s members joining the picket line and of his own address to the large and raucous crowd assembled at the strike committee’s public meeting.26 It becomes clear through Rader’s account that he and other members of Local 401 had a wide range of social interests during the New Deal era. Moreover, Rader reveals that Local 401 was an organization through which these instructors could show their solidarity with organized labor and support progressive causes.

Unfortunately for Local 401, solidarity and cooperation with such a wide base of organizations would prove increasingly difficult over the years. This was due primarily to many of the political alliances and relationships made by several key members of 401 during this period of rapid organization and expanding social consciousness. Many of the organizations Rader and his union colleagues associated themselves with were heavily influenced by CP members or responsive to Communist doctrine. While Rader himself insisted on never having been a CP member—indeed his conviction on that charge by the Canwell Committee was later overturned—he did admit to joining in causes and organizations such as the United Front that he knew contained Communist elements. He explained, “I reasoned that a good cause should not be deserted merely because Communists supported it … I observed that there was scarcely a liberal organization anywhere in the land that did not include Communists within it.”27 Rader goes on to explain that the brand of communism espoused by most in those years was not the same as in later years, and that under their international spokesman, Maxim Litvinov, the Communists were putting their support behind the Roosevelt administration.

Rader took pains to explain his activism in these leftist groups because it was his and his colleagues’s participation in these groups during the Depression that raised the suspicion of the Un-American Activities board and prompted the Canwell investigation. It was these groups and Local 401 that investigators would label “communist front” organizations and use as evidence of University of Washington faculty involvement with the CP.28 Many of the instructors at the University who joined Local 401 at its inception did so to help diminish the animosity that many quarters of organized labor harbored toward University faculty. Although many of the teachers in Local 401 had serious objections to “thug” elements within Dave Beck’s AFL-affiliated Teamsters, their participation in the union was a step toward bridging gaps while seeking common solutions to the Depression.29 While participating in Local 401, the WCF, and other United Front organizations, many members made contacts with members of the CP and were asked to join. While many, like Rader, declined to join the CP because of its “narrow dogmatism” and “confusion of means and ends,”30 others like Harold Eby and Joseph Butterworth felt that joining the CP did not compromise their ideological beliefs.31 The development of Local 401 included considerable radical influence and input from either members of the CP or those sympathetic to its platform. In the mid-thirties these were not especially significant charges, but by the late forties they came to be nearly damning.

Throughout the 1930s, Local 401 grew in membership and notoriety on campus. In a 1937 edition of the AFT’s journal American Teacher, the Executive Board of the Local reported on its activities on campus and its expanding member rolls. Citing dinner and theater parties for prospective members as ways of making friends on campus, the Local seemed to be gaining a favorable response from many faculty members. The Local also reported that sending out occasional letters to faculty regarding its stance on current legislative issues was an effective way of making itself known. The brief article concluded, “We have found that the way to grow is to make our voice heard on campus issues and then take full credit and all the publicity we can get from our accomplishments.”32 Some campus activities that the Local participated in included defending liberal teachers against discrimination from administrators and protecting the jobs of married women teachers at the university.33 Though the article in which this report appears does not detail what sort of action the Local was taking in these matters, it can be assumed that it consisted of their usual statements of protest and letters sent to faculty. What becomes even more apparent is the continued friction between the University administration and liberal instructors on campus, a conflict that Local 401 was not shying away from.

Local 401 not only took part in pressing campus issues but also involved itself in the ongoing AFT debate on whether to affiliate with the newly powerful Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which advocated an inclusive industry-wide unionism, or stay with the AFL, who separated skilled workers from each other within a single industry. In the September-October 1937 issue of American Teacher Selden Menefee of Local 401 argued that that the AFT should “cast their lot” with the CIO and disaffiliate with the AFL and its “outmoded craft-unionism.” Menefee and many other members the Local were especially soured against Dave Beck and his Teamster “goon squad” who were dominating the AFL in Washington and impeding the growth of the more progressive CIO.34 Beck’s influence was seen by the Local as both corrupt and instrumental in blocking the widespread worker’s solidarity that they saw as the goal of organized labor.35 Although the AFT eventually decided to remain with the AFL, the Local’s stance on this issue illustrates 401’s desire to push the AFT further to the left.

Cold War

As the 1930s gave way to the 1940s, Local 401 continued to show its leftist leanings. The reaction of the Local to European events at the onset of World War II further incriminated them in the eyes of both conservative labor and University officials. Before the Nazi invasion of Russia in 1941, Local 401 had strongly opposed the war, especially the United State’s involvement with the Lend-Lease Act. Then the Local seemed to make a swift about-face after the Nazi invasion by putting its support behind Lend-Lease and American preparedness for war.36 This quick change of doctrine was suspiciously close to the zigzags of the international CP line and raised eyebrows among University of Washington administrators. Evidently, this association with the CP proved too close for comfort for many of the members of Local 401, and is seen by some for diminishing the Local’s ranks during World War II.37 By the close of World War II, this behavior provided fodder for the Canwell Committee and others seeking to charge members of 401 with CP membership and loyalty to the USSR.

In Washington State the political climate was highly charged with anti-Soviet sentiment during the 1946 election, as Republican candidates sought to unseat the opposing New Deal-friendly Democratic incumbents.

Echoing the concerns of Republican politicians around the country, the Washington Republicans made Decmocratic Party involvement in United Front organizations the target of their election campaigns. A byproduct of this renewed conservative zeal was the appointment of the Joint Legislative Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities led by freshman Republican State Representative Albert Canwell whose purpose was to sniff out CP members from among the ranks of Washington’s educators.38 Accompanying this conservative drive to flush out Communists from the universities was a prolonged attack by the Hearst-owned Seattle Post-Intelligencer against University of Washington faculty. Led by columnist Fed Niendorff, the P-I published a series of damaging articles filled with innuendo and outright accusations that the unniversity was in fact infested with Communists.39 Some of the main targets of these attacks were radical labor organizations that had been active during the Depression, and on the University of Washington campus, none was more prominent than Local 401.

In this increasingly reactionary climate the members of Local 401 were aware of how tenuous their position had become. After the war the Local had done much to alienate themselves from conservative elements in the campus administration, state politics, and the press. Some more of their radical activities included protesting Truman’s policy of intervention in Greece and China, where the United States was trying to eliminate Communist influence, and supporting a rally near campus for progressive Democrat Henry Wallace.40 But even in the face of possible investigation, the Local remained active and involved in controversial issues.

Canwell Commitee Investigations

Professor Ralph Gundlach, attorney John Caughlan, and state Communist Party Secretary Clayton van Lydegraf wait for the regents to rule on Gundlach's case. The regents voted unanimously to fire Gundlach. Photo courtesy of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History and Industry. For more on the case: Nancy Wick "Seeing Red" Columns December 1997.Perceiving the threat that the Canwell Committee might pose to their Local, the members of 401 went to work on finding ways to defend their position. Almost immediately after the appointment of the House Un-American Activities Committee in January 1947, Local 401 met with Washington State Federation of Teachers president Harold Paschal and vice-president Elmer Miller in a WSFT public meeting to discuss possible actions the Local might take.41 Out of this meeting came the Washington Committee on Academic Freedom. This was a citizens committee devoted to defending the principle of academic freedom throughout the Canwell trials.42

Within the Local there were many disagreements on how to deal with the possibility of being investigated. According to Rader, there were “fierce discussions between those who advocated unilateral defiance of the committee and those who favored cooperation with the campus chapter of the American Association of University Professors.”43 Those on the side of a stand-alone act of defiance included Ralph Gundlach and Herbert Phillips, both of whom were officers in the Local and often frustrated with what they perceived as the Local’s lack of initiative. On the opposing side, those who advocated developing a wider base of support were Rader and Albert Franzke, who both served presidential terms during the years of 1947 and 1948.44 This tension within the Local is one of the more interesting story lines in the life of Local 401.

In attempting to protect its members against the Canwell Committee, Local 401 faced a major challenge in finding support. From the Local’s minutes we can see that in meetings to discuss possible action, the subject of communism was never swept entirely under the rug but was dealt with very carefully. In discussing a draft of a possible letter to be sent out to faculty members, Rader is said to have urged its author to “stress principles and to dodge nothing; to urge the rights of the individual, even if members of such groups as the communist party.”45 The Local was in a difficult situation where if it acted out individually in protest of the Canwell Committee it would likely attract more negative attention than it had already. The alternative was to find a wider base of support and legitimacy. The first place the Local turned was toward the AAUP.46 Towards the end of 1947, this proved to be their only real choice after University of Washington President Raymond Allen urged them not to take direct action against the Committee. The Local complied with the President’s wishes.

On December 3, 1947 the Local sent out a letter to the University of Washington chapter of the AAUP seeking cooperation and advice. The letter stressed that the two unions had “worked together in the past” and that the AAUP should inform outside forces that it “is going to defend the legitimate rights of the teachers at the University.” The letter also brought up that the press had recognized the AAUP’s success in slowing down similar investigations in the past.47 Two weeks later the Local received a mixed response. UW AAUP president R.G. Tyler informed 401 that he had read their request at his last meeting and “at that time we decided upon a program which involved watchful waiting so far as any campus activities are concerned.”48 This promise of “watchful waiting,” while not a refusal of assistance, was hardly enough to ease the growing anxiety of several 401 members who faced the very real possibility of being subpoenaed by the Canwell Committee.

The Local found itself beset with more internal troubles. By the end of January 1948, 401’s financial condition had worsened considerably. Treasurer Bertha Kuhn abandoned her position complaining of too little assistance in her bookkeeping and of the job’s interference with her scholarship. In a letter of resignation she went on to say that much of the Local’s financial woes could be blamed on the failure of many of its members to pay their dues.49 She then notified the executive board that she was withdrawing from the union and her position treasurer was handed over to the already overburdened corresponding secretary Margaret C. Walters.50 Besides the pressure of dealing with the Canwell Committee, Local 401 was faced with an increasingly demoralized membership.

In the minutes we can also see that by February the membership of Local 401 was growing more impatient and divided. At a meeting held on February 11, 1948, both Gundlach and Phillips were vocal in their belief that the Local should act in its own defense rather than waiting for additional support. Sitting president Franzke and secretary Walters stressed their belief in a low key and cooperative approach, warning that open action might only provoke the Canwell Committee further. By the end of the meeting Phillip’s position had softened but only with great reluctance.51 At the April 27th meeting, Phillips returned to his position that the Local should send out a letter of protest. Once again, Franzke and Rader argued against such action and continued to urge 401 to develop a wider base of support including the AAUP and community groups like the Quakers.52 By the time 401 met on May 24, the search for outside help had expanded. In this meeting Franzke reported to the rest of the assembled membership that he had unsuccessfully tried to convince the Seattle Times to run a “smear” campaign against the P-I. Phillips spoke in favor of sending a letter to the WSFT requesting that the Board take a statewide stand, mobilizing as much support as possible while alerting the people of Washington to the dangers that the Un-American Activities Committee might pose to academic freedom. His motion was passed after it was modified to “use the university situation as only one part of action on a wider front.”53 But by the middle of May the Canwell Committee had begun to subpoena members of 401 for questioning and the Local had done little to circumvent this action.

The University of Washington professors requested to appear before the Un-American Activities Committee included Joseph Butterworth (English), Ralph Gundlach (Psychology), Herbert Phillips (Philosophy), E. Harold Eby (English), Garland Ethel (English), Melville Jacobs (Anthropology), and Melvin Rader (Philosophy). All were members of AFT Local 401. They were scheduled to face trial in July on charges of belonging to the Communist Party and the future of their careers seemed in jeopardy.54

While these members had not given up hope on the possibilities of the Local to defend its members, certain individuals were disappointed in its performance. In a letter to a friend, Gundlach confided that the “teachers union has done little or nothing, several of its top members being interested in personal safety.”55 In a separate letter sent out that same day Gundlach told three of his colleagues in the Local that, “the Teachers Union has a special responsibility. As I calculate, the persons subpoenaed represent 8 or more years of presidency in the Union.” He then went on to state that some possible action for the Local could include appeals for attorneys, the formation of a lawyer pool, finding more union support, and getting more money, “of course.”56 There is no evidence that the Local or the WSFT accomplished any of these things.

At the conclusion of the Canwell hearings, six of the professors were made to appear before the University of Washington Senate Faculty Committee. Jacobs, Ethel, and Eby admitted to CP membership in the past but not presently. Gundlach denied having ever been a Communist while both Butterworth and Phillips admitted to current membership in the Party. After this trial, the Regents decided in January of 1949 that Gundlach, Butterworth, and Phillips were to be dismissed and Jacobs, Ethel, and Eby would be placed on two-year probation.57

Expelled from the AFT

On August 16, just weeks after the conclusion of the Canwell hearings, Local 401 received a letter from AFT national secretary-treasurer Irvin Kuenzli stating that the national office was planning and investigation of the Local in early September.58 To this communication, M.C. Walters, secretary and treasurer of the Local, replied that early September would not be a good time since most members were away for the summer and involved with their academic work. Waters also told Kuenzli that no new officers had been elected, no dues were coming in, that no one could promise to be present at the investigation, and that she was treasurer only because no one else would take the job.59 In another letter to Kuenzli, Waters crystallized what must have been the feelings of many members at having the Local investigated: “I warn you that if anyone even hints that I have done anything more than I have done, I shall blow up with a loud report, because I have personally enjoyed one hell of a summer.”60 Despite objections by Local 401 the AFT investigating committee spent September 8 and 9 investigating the Local for evidence of subversive activities.

In order to understand the actions of the AFT leading up to and after its investigation of Local 401 we must look at the AFT’s policy on Communism within its ranks by the late 1930s. Beginning in the mid-thirties, New York City AFT Local 5 had shown signs of being heavily influenced by Communist Party members. By 1938, AFL president William Green had become wary of the AFT’s growing reputation as an organization sympathetic to communism and began complaining to the AFT national. Many in the AFT leadership took heed of Green’s concern and took action to mitigate the AFT’s radical image. Since the AFL could only disaffiliate with the entire AFT and not individual Locals, the AFT executive council began its own investigation of Local 5, and in 1941 they were expelled along with Local 537 in New York and Local 192 in Philadelphia. These three locals were found to be overly sympathetic toward communist influence and guilty of “dual unionism.”61 In this sense, “dual unionism” meant a willingness to cooperate with the CIO in organizing other labor radicals in New York.62 By 1941, the AFT had demonstrated its willingness to expel wayward locals in order to protect its relationship with the AFL and distance itself from both the Communist Party and the CIO. With their decisive turn away from radicalism in the early 1940s the AFT had shown its devotion to driving Communists and Communist sympathizers from its ranks and had established a policy toward the radical left that did not include the outlook or membership of Local 401.

On September 20, 1948, Local 401 received news from the national office that it would, “cease to exist as an affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers.”63 The response from the Local was one of frustration and disappointment. Walters wrote to the national that “the action showed little comprehension of the fight for Civil Liberties and academic freedom” and that “our future actions are at present uncertain.” Walters went on to write that the Local might continue to function without recognition from the AFT, although the negative press publicity had effectively scared off many of the more conservative members.64

University of Washington Local 401 had lost its charter thirteen years after first affiliating. In the investigating committee’s explanation, it stated “the minutes and publicity throughout the years revealed little attention to educational problems and teacher welfare, but strong emphasis on political activities.”65 Although Walters hinted at the possibility of continuing the Local without AFT recognition, the remaining members of Local 401 still interested in AFT membership were subsequently absorbed by Seattle Local 200.66

Local 401 had tried and failed to find a wide base of support for what it described as a defense of academic freedom. The AAUP had not been forthcoming with substantial support; its policy of “watchful waiting” was certainly not the solution to 401’s problems. Where then, it might be asked, was the support of the WSFT during 401’s time of need?

Perhaps the WSFT leadership’s disposition following the Canwell hearings and AFT expulsion can provide some insight. On October 23, 1948, just a month after the revocation of 401’s charter, a pre-convention meeting of WSFT delegates met to form resolutions for the annual convention later in November. At this meeting, the subject of what stance to take on the AFT’s action toward Local 401 arose. One member of the resolution committee moved that WSFT president Harold Paschal head up a committee to look into the national’s handling of 401. After two failed attempts to pass the resolution it was defeated with only two delegates voting in support.67 The two delegates most vocal against the resolution were Elmer Miller and Walter Koenig from Seattle High School Local 200. Earl Miller was past president of the WSFT as well as being regional vice-president for the AFT national. Walter Koenig was the current president of Local 200. Neither of these men, along with sitting WSFT president Paschal, demonstrated serious interest in pursuing a resolution or possibly opposing the AFT national’s action. Eventually, Paschal ruled the resolution out of order, thereby making it impossible for it to reach the floor of the annual convention.68

This apparent effort of key members of the WSFT to distance themselves from the 401 controversy was echoed by Koenig in the January edition of Local 200’s newsletter, Seattle Teacher. In his article, Koenig repeated the AFT platform of intolerance for infiltration by members with allegiance to any totalitarian power be it fascist, Nazi, or Communist. He went on to stress the “clear cut” nature of “democratic education” and stressed that his Local remained “independent” and would “intend to keep from being influenced by any group.” Although 401 was not referenced directly by Koenig, it is clear that he and his Local were much more interested in following AFT doctrine than defending the principles of academic freedom along with their neighboring college Local. In style and substance, 401 had shown itself to be miles apart from their fellow teacher unionists at both the national and local level.69

University of Washington Local 401 was born at the height of the New Deal amidst the heady political atmosphere of Seattle during the Great Depression. In many ways, its member’s identification with the AFT was based around a shared desire to voice wider political concerns and develop policy platforms on local and global events. For many of its members, the University Local was also an organization by which they could cultivate a closer relationship with organized labor and express solidarity with the poor and the unemployed against fascism and the excesses of global capitalism.

At the professional level, Local 401 spoke out in defense of University of Washington instructors and against what they saw as unfair labor practices practiced by campus administration. Their stance on these issues appears to have gained some significant traction among a number of faculty members. However, on one of their most treasured practical professional issues, academic freedom, 401 found itself constrained by fear in the face of the Canwell Committee and proved unwilling to make much of a stand of its own. In the end, there is no evidence that Local 401 made concrete steps toward bettering conditions for the college teacher other than to highlight their opposition to what they perceived as unfair treatment of instructors. Partially, however, this failure can be also be ascribed to the lack of support the Local received from fellow unionists when they came under attack.

While for at least a short time in the 1930s, 401’s orientation seemed to flow within significant currents of the AFT, they had, by the end of World War II, found themselves far beyond their national and local leadership’s political comfort zone. By the time pressure was being applied by the Canwell Committee, the Local had strayed too far left and their members’ hopes of building a broad range of support for the defense of academic freedom was improbable if not impossible. Indeed, Local 401 seemed to find itself with very few if any allies in the Cold War. Furthermore, Local 401’s increasing inability to maintain its books and pay its dues indicates that its membership was waning in union enthusiasm while its surviving core of founding members maintained a stronger interested in geopolitics than operating as a viable union affiliate. This was at least the position of the AFT national office as it expelled the thirteen-year old Local and brought an end to a fascinating chapter in Washington history.

Copyright (c) 2009, Andrew Knudsen

1 William Edward Eaton, The American Federation of Teachers, 1916-1961: A History of the Movement, Southern Illinois University Press; 1975

2 Melvin Rader, False Witness, University of Washington Press; 1969. P. 31

4 Rader, False Witness. P. 31

5 Membership and Finances, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folders 4 and 5.

6 Membership, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 4.

7 Eaton, The American Federation of Teachers, pp. 58-59.

8 Minutes and Correspondence, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folders 1 and 2.

9 Minutes and Correspondence, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folders 1 and 2, October 1946.

10 Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folders 1 and 2. The AAUP and Local no. 401 had worked together on sending out a memorandum on tenure in 1946.

11 Rader, False Witness, p. 30.

12 Records of Local 401 members at WSFT Annual Conventions, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 1.

13 Albert Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front, University of Washington; 1975.

14 Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front, Ch. 3-4.

15 Rader, False Witness, p. 32.

16 Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front, p. 229.

17 Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front, p. 167.

18 Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front, p. 167.

19 Eaton, The American Federation of Teachers, p.106.

20 Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front, p. 168. It was the President’s view that an instructor at the University of Washington should not devote too much time and energy to activities beyond his teaching duties.

21 Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front, p. 168.

22 Acena, The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front, p. 168.

23 Sunday News, February 7, 1937

24 Rader, False Witness, p.7.

26 Rader, False Witness, p. 33.

27 Rader, False Witness, p. 31.

28 Jane Sanders, Cold War on the Campus: Academic Freedom at the University of Washington, 1946-64, University of Washington Press, 1979. P. 38.

29 Sanders, Cold War on the Campus, p.7.

30 Rader, False Witness, p. 41.

31 Sanders, Cold War on the Campus, p. 68.

32 American Teacher, March-April 1937, Campus Issues, p. 12.

33 American Teacher, January-February 1938, News of the Northwest, p. 25.

34 American Teacher, September-October 1937, For the Affirmative, p. 26. Sanders, Cold War on the Campus, p.7.

35 American Teacher, September-October 1937, For the Affirmative, p. 26.

36 Eaton, The American Federation of Teachers, p. 132.

37 Sanders, Cold War on the Campus, p.7.

38 Sanders, Cold War on the Campus, pp. 14-16.

39 Rader, False Witness, p. 5.

40 Minutes, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, March 1947, folder 2. Sanders, Cold War on the Campus, p. 7.

41 Minutes, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, January 28, 1937, folder 2.

42 Rader, False Witness, p. 7.

43 Rader, False Witness, p. 7.

44Minutes, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 2. This conflict really began to take shape around April of 1948.

45 Minutes, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, January 28, 1947, Box 1, folder 2.

46 The Local began to write letters to the AAUP around the beginning of December.

47 Letter sent to R.G. Tyler of the AAUP, December 3, 1947, Correspondence, Teachers, American Federation of , University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 1.

48 Letter from R.G. Tyler to M.C. Walters, January 30, 1948, Correspondence, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 1.

49 Membership and Finance, Teachers, American Federation of, University ofWashington Local no. 401, Box 1, folders 4 and 5. The records show that only a handful of 401’s membership had been marked as paying their dues in 1947 and 948.

50 Letter from Bertha Kuhn to M.C. Walters, January 30, 1948, Correspondence, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 1.

51 Minutes, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 2, February 11, 1948.

52 Minutes, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 2, April 27, 1948.

53 Minutes, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 2, May 24, 1948.

55 Letter from Ralph Gundlach to “Cliff”, June 28, 1948, Ralph Gundlach Papers, Box 1, folder 10.

56 Letter from Ralph Gundlach to E.H. Eby, June 28, 1948, Ralph Gundlach Papers, Box 1, folder 10.

57 Sanders, Cold War on the Campus, pp.73-76.

58 Letter from Irvin R. Kuenzli to M.C. Walters, August 16, 1948, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 1.

59 Letter from M.C. Walters to Kuenzli, August 19, 1948, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 1.

60 Letter from M.C. Walters to Kuenzli, September 1, 1948, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 1.

61 Eaton, The American Federation of Teachers, p. 119.

62 Eaton, The American Federation of Teachers, p. 119.

63 Letter from Kuenzli to M.C. Walters, September 20, 1948, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 1.

64 Letter from M.C. Walters to Kuenzli, October 11, 1948, Teachers, American Federation of, University of Washington Local no. 401, Box 1, folder 1.

65American Teacher, February 1949, Statement of Investigation of Local 401 the University of Washington Teachers Union, p.9.

66Eaton, The American Federation of Teachers, p. 132.

67 Minutes, Washington State Federation of Teachers, “Annual Convention”, October 23, 1948, Box 1, folder 4, University of Washington Manuscripts and Archives.

68 Minutes, Washington State Federation of Teachers, “Annual Convention”, October 23,1948, Box 1, folder 4.

69 Seattle Teacher, January 1949, in Washington State Federation of Teachers, Box 1, folder 7.