Never before had the government subsidized the arts to such a degree, employing thousands of artists, including upwards of 50 in Washington State, at wages of $38 - $46.50/week, to produce over 400 murals, 6,800 easel paintings, 650 sculptures and 2,600 print designs, among other accomplishments.[2] The PWAP demonstrated that culture could constitute work and that those active in the cultural industries were, by extension, worthy of public support. By creating the program, the Roosevelt Administration, in the words of PWAP Director Edward Bruce, “recognized that the artist, like the laborer, capitalist and office worker, eats, drinks and has a family, and pays rent, thus contradicting the old superstition that the painter and the sculptor live in attics and exist on inspiration.”[3]

The idea behind the PWAP, as well as later New Deal visual arts programs, came from Mexico. In 1922, the Mexican federal government under General Álvaro Obregón began hiring artists, including Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, to paint murals in public buildings, with the goal of promoting nationalism and social cohesion in the wake of the long and violent (roughly 1910-1920) revolutionary period. Building on the traditions of Aztec painters, the muralists used fresco techniques first discovered through archaeological work at Teotihuacán, among the most significant indigenous historical sites in the Americas.[4]

Though short-lived, the Mexican mural program caught the attention of a number of American artists and intellectuals, who lived in Mexico during the late 1920’s and early 1930’s. Among those who studied the fresco techniques were three prominent artists from the Pacific Northwest: Ambrose Patterson, Mark Tobey and Kenneth Callahan, all of whom would later participate in one form or another in the New Deal visual arts programs.

[5] The Mexican mural program also had an impact on another visiting American, George Biddle. The son of a prominent Philadelphia family, Biddle attended boarding school at Groton Academy in Connecticut before entering Harvard University. It was at Groton where he met and became friends with the future president Franklin D. Roosevelt, a relationship that proved critical to the early history of the PWAP.

In May 1933, Biddle, a well-known artist in his own right, wrote a now famous “Dear Franklin” letter to the recently elected Roosevelt, urging him to create a new program, modeled on the Mexican example, which would pay painters and other artists at “plumber’s wages” to decorate government buildings throughout the country.[6] Not only would the initiative create jobs, it would also provide an opportunity, Biddle noted to Roosevelt, for artists to represent “the social ideals you are struggling to achieve.”[7] Indeed, he went on to say, a Mexican-style program “could soon result, for the first time in our history, in a vital national expression.”[8]

The President was intrigued. “It is very delightful to hear from you and I am interested in your suggestion in regard to the expression of modern art through mural paintings,” he wrote. [9] Yet, Roosevelt also harbored “grave doubts concerning the political consequences of government supporting art for its own sake.”[10] Just how politically radical would the artists be and how might their work affect the public’s perception of the New Deal and, by extension, the President himself? This tension, between the politics of art and the art of politics, proved especially thorny, troubling all the New Deal cultural programs, in theater, writing, music and the visual arts, throughout the duration of the Great Depression. In the end, Roosevelt set aside his qualms (for the time being) and referred Biddle to Lawrence W. Robert, Jr. an official with the Treasury Department, who, with the help of Eleanor Roosevelt and other New Dealers, quickly organized the Advisory Committee to the Treasury on Fine Arts – a new body charged with assisting the nation’s artists.[11]

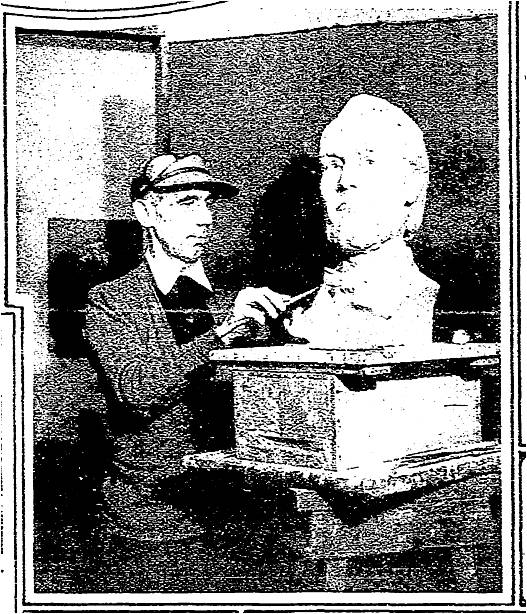

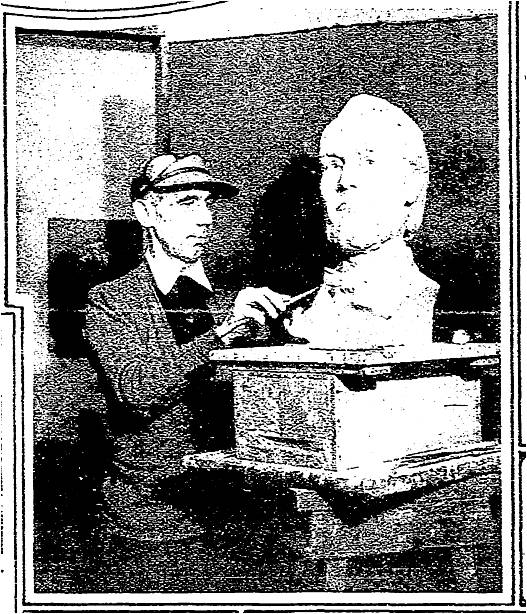

In this image, from the March 4, 1934, edition of the Seattle Daily Times, PWAP Sculptor James Wehn is pictured working on a bust of Dr. David "Doc" Maynard, Seattle's first physician, who arrived in the area in 1852. History proved a popular theme for PWAP works, which sought to celebrate the people and story of the United States during the grim days of the Great Depression. On December 8, 1933, only a few short months after Biddle’s letter and the establishment of the Advisory Committee, Harry Hopkins, one of Roosevelt’s closest advisors and the director of the Civil Works Administration (CWA), announced that over $1 million in CWA monies would go to support artists under the auspices of a new Treasury Department-administered program – the PWAP. Hopkins himself had been an early supporter of the idea and likely played a role in shepherding it through the approval process.[12] Edward Bruce, a lawyer, Treasury Department official and established artist, became the PWAP Director, with Forbes Watson, an art critic, named Technical Advisor and Edward Rowan, as Assistant Director. All three men believed strongly in the value of publicly funded art and advocated on behalf of the program in Washington, D.C.

The PWAP divided the country into 16 regions, each with a director and a volunteer committee that impartially selected and employed artists. Project set-up took place quickly; indeed, by January 1934, over 1,400 artists and 27 laborers were already at work.[13] Employment and pay structures matched the CWA more generally, which translated into a higher and simpler wage structure than the one developed in later years for the Federal Art Project.[14]

During its six months of operation, the project employed some 3,700 artists, allocated according to each region’s population. Active in all fifty states, these men and women completed more than 15,600 works of art, which were visible in federal, state and municipal buildings as well as parks and museums. In addition, the artists also documented important federal initiatives then underway, including the Civilian Conservation Corps and the construction of large public works, like the Boulder Dam.[15] Not only did the PWAP provide work, it also restored self-respect and confidence to artists. The words of one artist to Director Bruce capture the sentiment, “I have a new outlook on life…a future that looked so dark and hopeless just a short while ago has changed completely.”[16]

Washington State, Oregon, Idaho and Montana comprised the Pacific Northwest region, with the largest share of artists allotted to the Evergreen State.[17] Burt Brown Barker served as Chairman of the area’s volunteer oversight committee. A Portland resident, Barker was director of the Portland Art Association and the Vice President of the University of Oregon. He was optimistic for the Pacific Northwest’s potential output, noting in a January 7, 1934, Seattle Daily Times article, “Because our mountain scenery is so vastly different from anything in the Midwest, I believe the work produced here will be exchanged with other parts of the country, although that is a part of the program not yet fully developed.”[18]

In the same 1934 piece, Barker also emphasized the PWAP’s dual – and at times conflicting – purposes. While fundamentally a relief effort, the program’s leadership, including administrators in Washington, D.C. and many regional officials like Barker, also hoped to raise the nation’s cultural awareness through exposure to high quality art, which sometimes resulted in high-profile artists receiving commissions, while impoverished, lesser-known individuals languished out of work. [19]

In June 1934, a Seattle Daily Times article commented that, “in the future’s estimate of the New Deal, possibly no one effort of amelioration will prove more interesting and more revolutionary in its cultural effects than the Public Works of Art Project." In fact, the PWAP did prove path-breaking, setting a new precedent for the relationship of government to the arts in the United States.A rigorous screening process overseen by volunteer committees sought to yield first-rate, authentically “American” works that contributed to building the country’s shared ethos and identity, much like the Mexican mural initiative of the 1920’s. [20] These sentiments echoed ideas expressed by Director Edward Bruce, who commented: We live in a heterogeneous country…But when the farmer, and the laborer, the village children and the storekeepers go to the nearest post office and see there, for example, a distinguished work of contemporary art depicting the main activities, or some notable events in the history of their own town, is it too much exaggeration to suggest that their interest will be increased and their imagination stirred?[21]

In Washington State, approximately 50 artists participated in the PWAP during its brief tenure. For the most part, their work conformed to the aesthetic and thematic forms of the “American Scene.” This movement stressed “regional and small town life and produced views of local color and straightforward celebrations of ideals such as community, democracy and hard work.” [22] It was also non-controversial and easily understood by diverse viewers unfamiliar with modern or abstract art.

Strict adherence to this approach was never required, but it did become dominant within the PWAP and to a lesser extent the Federal Art Project that followed. Assistant Director Edward Rowan, for instance, commented that if an artist did have the “imagination and vision to see the beauty and the possibility for aesthetic expression in the subject matter of his own country,” he or she not be considered for the program.[23] Such attitudes created rifts with many artists and art critics, who preferred more experimental methods and subject matter. It also caused problems for politically active artists, whose work challenged celebratory history and patriotic storylines.

In the program’s final month, June 1934, a Seattle Daily Times article celebrated the achievements of Washington State artists. In particular, the paper highlighted the completion of two large, carved, cedar bas-relief bound for local schools. The first, some 10 feet long and 3 feet high, by Marion "Ivan" Kelez, depicted the landing of Arthur Denny’s Party at Alki Point in what is now West Seattle on November 13, 1851. Among the first Euro-Americans to settle permanently in the region, the Denny Party served as a powerful and romantic symbol of the Pacific Northwest’s not so distant past. Inscribed on the panel was a quote from Roberta Frye Watt, the granddaughter of Arthur Denny: "Surely, we owe these pioneers — those pilgrims of ours a debt of gratitude. Oh, speak not lightly, the word 'pioneer' but gratefully, lovingly, reverently."[24]

The bas-relief also referenced the indigenous peoples who were living in their ancestral homelands along the shores of Puget Sound when the Denny Party arrived. In addition to the presence of a Native fisherman in the corner of the scene, there is also a quote, attributed to Chief Seattle (or si?al in his native Lushootseed language) of the Suquamish and Duwamish tribes, that reads: "When your children's children think themselves alone in the field, the store, the shop, upon the highway, or in the silence of the pathless woods, they will not be alone. At night when the streets of your cities and villages are silent and you think them deserted, they will still throng with the returning hosts that once filled them and still love this beautiful land. The white man will never be alone."[25]

Less detail is available on the second bas-relief, which, the Seattle Daily Times reported, envisioned the “coming together of boys and girls of all nations to make the ideal high school civilization, to be placed in the entry way of a particularly cosmopolitan school.”[26] These subjects, a romanticized pioneer past and an almost utopian, egalitarian present and future, celebrated mainstream ideas of American idealism, hard work and perseverance at a moment of extreme national distress. The panels, which were by no means unique in their approach, offered viewers a vision of hope and unity amidst the economic and social turmoil of the Depression. They sought to re-affirm an - at times - wavering faith in the possibilities of liberalism, American exceptionalism and industrial capitalism, while downplaying or ignoring the often painful complexities of the nation’s past, such as violence and discrimination against Native peoples.

Other works produced in Washington State under the auspices PWAP included: murals in the Women’s Recreation Building and the Oceanographic Building at the University of Washington; an extensive marine life diorama for the University Museum; paintings in a Seattle senior citizens home; iron gates for a memorial gateway to the south park playfield in Seattle; samples of early American weaving from the southern and eastern United States for the state school system; wood carvings of mountains and other nature scenes by a “young Norwegian” in Tacoma; and nursery school-themed art for government-run daycare centers.

This painting, Wheelbarrow, by Morris Graves, was completed as part of the Public Works of Art Project in 1934. Photo courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum (Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Pacific Northwest artists active in the PWAP also received national recognition for their work, highlighted by the inclusion of 15 Washington State artists, including Morriss Graves, who would gain acclaim as a member of the Northwest School, in a 1934 exhibit at the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington D.C. After reviewing the show, President and Mrs. Roosevelt selected a handful of works to hang in the White House. Among those chosen was “The Timber Bucker,” a painting by Seattle artists Ernest Norling, which depicted life in the state’s CCC Camps.[27] Other works, not sent to Washington D.C., went on exhibit at the Seattle Art Museum during the spring and summer of 1934.

In a 1964 oral history interview, Norling remembered his time on the PWAP documenting the Civilian Conservation Corps camps. "The work was every interesting, " he recalled. "I went out to Parkers Island to the camp which is now Omerand State Park and there were at least 200 boys there and they were building a road up to the top of Mount Constitution. I made sketches of this work that they were doing. They were very interested in anything mechanical. They could take two men on a crosscut saw and saw a log off in five minutes but they would work an hour or two on a power saw to get it going, to you know how they... But, they were nice boys. We went up on the Hood Canal project and that was much the same. They were road building and improving the area there. And following that came the mural project." [28]

During a brief six months, the Public Works of Art Program managed to upend many long held notions of the proper relationship between government and the arts in the United States. Rather than rely solely on private patronage, which had largely dried up during the Great Depression, artists could now look to the government as a partner and a sponsor of their work. In return, artists dealt largely with themes “American” in nature, depicting places, people and stories familiar to the population at large. PWAP administrator Forbes Watson, who went on to play a role in other New Deal arts initiatives, summarized the program’s impact as follows:

“Before 1933…we had a large, groping, hungry public which looked to art as a means whereby its cultivation and outlook on life could be broadened. This was a public which, thanks to its idealistic optimism, did not realize the facts about the artist. Suddenly a country which generally speaking wanted to be tenderly cultivated without buying was transformed into a country which overnight became the largest purchaser of art in the making that the world has ever known.”[29]

Copyright (c) 2012, Eleanor Mahoney

[1] Margaret Prosser, "Needy Artists Greatly Aided by Government," Seattle Daily Times, June 17, 1934, p.8.

[2] Bruce Bustard, A New Deal for the Arts (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration in association with the University of Washington Press, 1997),6.

[3] Judith G. Keyser, The New Deal Murals in Washington State: Communication and Popular Democracy, Thesis (M.A.)--University of Washington, 1982), 39.

[9] William Francis McDonald, Federal Relief Administration and the Arts: The Origins and Administrative History of the Arts Projects of the Works Progress Administration. (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1969), 358.

[11] Martin R. Kalfatovic, The New Deal Fine Arts Projects: A Bibliography, 1933-1992 (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1994), xxiii.

[17] According to Baker, the largest share of the regional money had been set aside for Washington State, as “the regional art committee feels its artists are capable of producing the largest amount of acceptable work,” from "American Art to be Given Impetus by C.W.A. Plan," Seattle Daily Times, January 7, 1934, p.4.

[19] Ibid. On this particular issue and the controversy it sometimes caused see McDonald, 366-367.

[23] Such controversies, however, did not impact the program in the Pacific Northwest region. Generally well received, the PWAP generated far less controversy or consternation on the political right and the left than the Federal One Programs (Theater, Art, Writing and Music). There were certainly criticisms, especially from those that felt that radicals controlled the program, but the presence of Edward Bruce, a conservative as Director, helped to quell such critiques.

[24] Sanjay Bhatt, "Alki Elementary's Historic Mural in Need of TLC," Seattle Times, January 1, 2005, accessed August 20, 2012, http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2002137505_alki01m.html.

[28] Oral history interview with Ernest Ralph Norling, 1964 Oct. 30, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, accessed August 19, 2012, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-ernest-ralph-norling-13113.