by Yifeng Hua

The number and size of advertisements declined significantly as the economy worsened in the early 1930s. This full page Bon Marche department store ad appeared in the Nov 15, 1931 edition. Collected by Anna Wong. It has been nearly 80 years since the Great Depression of the 1930s and we are facing another global economic crisis. It is time to review the past to see what experience we can draw on for our future. An analysis of the advertisements run in The Seattle Times during the Great Depression of the 1930s will give us a revealing picture of Depression-era Seattle society, and will cast light on what we can do to cope with the current economic crisis.

The number and size of advertisements declined significantly as the economy worsened in the early 1930s. This full page Bon Marche department store ad appeared in the Nov 15, 1931 edition. Collected by Anna Wong. It has been nearly 80 years since the Great Depression of the 1930s and we are facing another global economic crisis. It is time to review the past to see what experience we can draw on for our future. An analysis of the advertisements run in The Seattle Times during the Great Depression of the 1930s will give us a revealing picture of Depression-era Seattle society, and will cast light on what we can do to cope with the current economic crisis.

Sample Selection Method

In order to obtain a better understanding of the unfolding of the Great Depression, I chose the years 1928, 1932, 1935 to survey, using the month of October as my test month in all these years. Spanning the years of 1928–1935 will enable us to get a better picture of Seattle (and a suggestive glimpse of the country in general) before, during, and after the Great Depression; to compare these different years; and to see the evolution of the Depression from start to finish.

Due to the limited time and space that I have, a comprehensive study of the advertising practice during this entire period is certainly impossible. However, for the sake of fair representation and randomization, I sampled advertisements in The Seattle Times on the dates of the 1st, 2nd, 14th, 15th, 29th, and 30th of every October during these three years.

Graph of Data

Advertisements in The Seattle Times

Type of Ad |

1928 |

1932 |

1935 |

Food |

11 (4.6%) |

17 (10%) |

9 (4%) |

Alcohol & |

1 (0.4%) |

5 (3%) |

8 (3.6%) |

Fashion |

Male: 14 (5.4%, Female 82 (34%) |

Male: 9 (5.2%), Female: 37 (21.6%) |

Male: 8 (3.6%), Female: 39 (17.4%) |

Automobiles |

13 (5.4%) |

2 (1.2%) |

10 (4.5%) |

Radios |

10 (4.1%) |

1 (0.6%) |

12 (5.4%) |

Furniture |

37 (15.4%) |

25 (14.6%) |

28 (12.5%) |

Entertainment |

29 (12%) |

35 (20.5%) |

40 (17.9%) |

Financial |

8 (3.3%) |

4 (2.3%) |

15 (6.7%) |

Men's products |

5 (2.1%) |

3 (1.8%) |

4 (1.8%) |

Women's |

20 (8.3%) |

19 (11.1%) |

23 (10.3%) |

Baby products |

3 (1.2%) |

2 (1.1%) |

1 (0.4%) |

Housing |

7 (3%) |

8 (4.7%) |

27 (12.1%) |

Diamond |

2 (0.8%) |

- |

- |

Promotional ads |

- |

4 (2.3%) |

- |

TOTAL |

241 |

171 |

224 |

Analysis

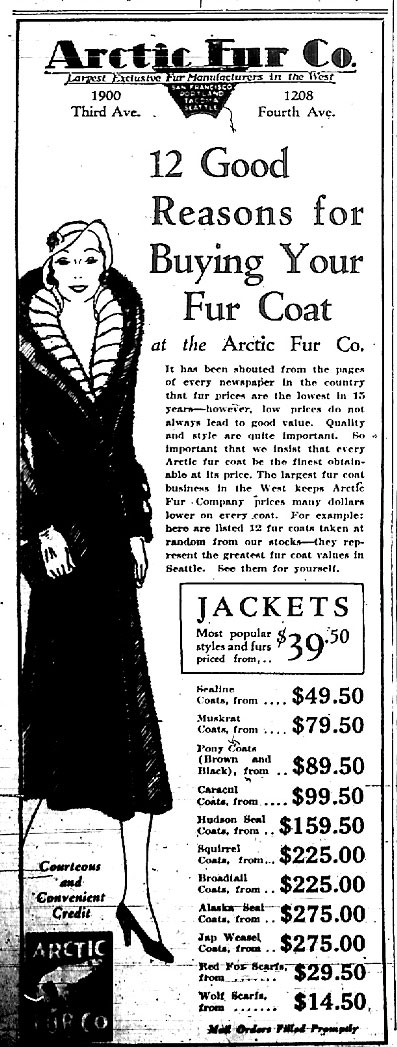

Prices fell in the early 1930s. Coats advertized here from Nov. 1, 1931 Seattle Times carried prices that were noticeably higher in this ad from Nov. 25, 1929. Ads collected by Anna Wong.The table above presents statistics about the number of advertisements run for each type of product and the approximate percentage of each type of advertisement in the total number of advertisements run. A careful analysis of these statistics reveals several trends about the advertisements run in The Seattle Times around the time of the Great Depression.

The first notable trend is the decline in the total number of advertisements during the Depression when compared with the period just before and after the Depression. In 1928, the year before the stock market crash, The Seattle Times ran a total of 241 advertisements; in 1935, after some economic recovery had begun, there were 224 advertisements; however, in 1932, the year in the middle of the Depression, there were just 171 advertisements, a sharp decline of around 30% from the other sample years. It was obvious that the economic crisis hit all businesses hard, from jewelers to food production.

The second, more interesting, trend is the respective changes in the advertisement categories in The Seattle Times during the period. Food, for example, is a kind of product that has a rather inelastic demand change. Interestingly, however, food advertisements went up significantly as a percentage of total advertisements during the Depression as compared to immediately before or after. In 1932, food advertisements made up 10% of the total advertisements, while they were just 4.6% in 1928 and 4% in 1935. Obviously, during the Great Depression, ordinary citizens had a hard time when they had little money for buying food. What was worse was that during that time the price of food went up nearly 30% than before: for example, a can of chips in 1928 was just $1 but was selling for $1.29 in 1932. Food companies had to raise the price and cut the number of employees to make the company run. This put the trade into a vicious cycle: the higher the price, the fewer goods were sold, and the more employees were fired. To sustain the industry, food companies had no choice but to increase advertising during the Great Depression. So, from the food advertisements, we can see the kind of effect the economic depression had on an industry that had a significant impact on people’s daily lives.

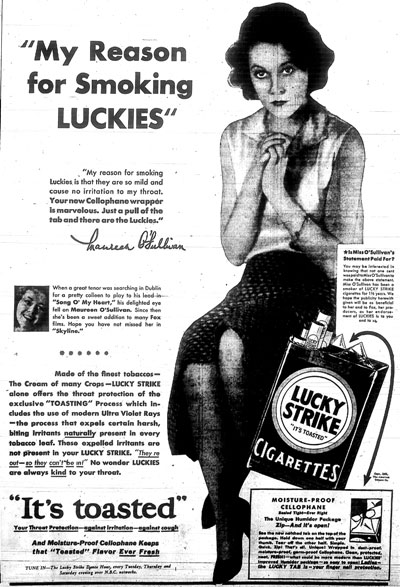

Another interesting trend is seen in the alcohol and tobacco advertisements, which saw a sharp increase from 0.4% in 1928 to 3.0% in 1932 and then to 3.6% in 1935. The tobacco and alcohol industries were rarely short of money, but they rarely put out a large number of advertisements because although consumers all knew that tobacco and alcohol were not good for their health, they never stopped consuming this kind of product. However, this situation changed during the Great Depression, when low income and other hardships drove more people to consume tobacco and alcohol for an escape from their harsh realities. The tobacco and alcohol industries capitalized on this opportunity by putting out more advertisements in newspapers. One interesting fact I found is that in nearly all these advertisements they used female characters, possibly to attract women to buy their products. By adding female consumers, they could maintain their revenue level even though they had to reduce prices overall during the Great Depression. Once the Depression was over, however, tobacco and alcohol companies did not stop advertising or go back down to their prior level of advertising; it was obviously hard for them to back away from this level of consumer interest. Sadly, tobacco and alcohol industries were the big winners in the Great Depression.

Seattle Times Nov.5, 1931. Collected by Anna Wong A reverse trend was found in the biggest advertising client, the fashion industry. In 1928, fashion companies took out 39.9% of the total advertising space in The Seattle Times. In 1932, the number dramatically dropped to 26.8%, and in 1935 was further reduced to 21%. The fashion companies always had the largest amount of advertising, but this is not surprising because the fashion industry changes rapidly and constant advertising is the best and often the only way to improve marketing. The data from the above table, however, clearly indicates that advertising by the fashion industry throughout the Depression was decreasing. An obvious reason, in my opinion, is that, unlike food, clothing has the most elastic demand! When the economic environment deteriorates and people’s income dramatically drops, everyone begins to cut his or her budget. Food is a basic necessity and cannot be cut since people have to eat to stay alive; transportation, likewise, is not an item that could be easily sacrificed. On the contrary, clothing is often a luxury, and since people usually have enough to wear, it is the first item to be cut from their budget. It was no surprise, then, that fewer people were buying clothing during the Great Depression, and the fashion companies clearly realized that putting out more advertisements during that time would be a waste of money. There is one intriguing question, however: Why did the number not increase in 1935, when clearly the economy had recovered? The answer, in my opinion, is that fashion companies lost so much money during the Great Depression that they had not fully recovered from the Depression and had no money to drastically increase advertising at that time.

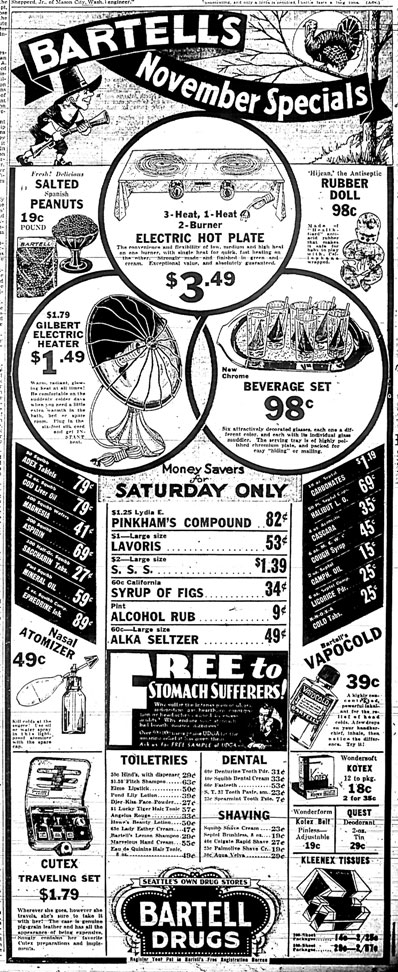

Advertizing volume had recovered by 1935. Ad collected by Anna Wong from Seattle Times Nov.8, 1935The same trend of decreasing advertisements was found with other luxury items, such as cars and diamonds. Naturally, advertising for these products are abundant during good economic times but would sharply decrease in bad economies. The period before the Great Depression was one of prosperity. Many people were living a prosperous life; a visible few were rich, and luxuries were selling well. We can see that the amount of advertising for cars, radios, and furniture was high in The Seattle Times, and we can even see some diamond advertisements. Once the Great Depression started, millions of people went from having excess income to having none. Hundreds of thousands of managers from big companies lost their jobs and had to turn to blue-collar jobs, such as selling apples on the street corners, to earn a living. There was no extra money for luxuries; the number one priority for most people was how to earn enough money for the next meal. Because of this, advertising for luxuries nearly disappeared. However, once the Great Depression was over, advertising for most of these luxuries, especially for cars and radios, increased to the level before the Great Depression, with the exception of some of the industries that suffered too much during the Depression.

Unlike other luxury or non-essential categories, the entertainment industry actually benefited from the Depression in more ways than it suffered. Entertainment industries, like movie companies, opera companies, theaters, and cinemas put out a lot of advertisements in newspapers. During the Great Depression, people might not have money to buy a car or a house, but they could often scrounge up some change to buy several movie or theater tickets and have a relatively inexpensive good time with their families or friends, which was sorely needed during a time of hardship. As a result, the more people went to the movies, the more products the movie companies turned out. To attract more people to movie theaters, advertising in newspapers seemed to most effective. As we can see from the table, from 1928 to 1935, the percentage of advertisements from the entertainment industry increased from 12% to 17.9%. The good thing is that the entertainment industry kept improving after the Great Depression, largely because it capitalized on its success during the Great Depression to create a stable and huge market. People began to incorporate going to the movies as a part of their life. With a large consumer base and ample talent, many good movies were produced during the 1930s: for example, The Adventure of Robin Hood (1938), Babes in Arms (1939) and Go into Your Dance (1935). It was also during this time that Hollywood came to be known around the world.

Hair care and hair products remained important throughout the depression. Seattle Times Nov.17, 1931. Collected by Anna Wong Finally, my analysis of advertisements in The Seattle Times found a very interesting gender disparity: the gap in advertising between women’s products and men’s products became smaller. If we divide the sum of advertisements for men’s fashion and men’s products by the sum of advertisements for women’s fashion and women’s products, we get a ratio of advertisements for men vs. advertisements for women. Before the Great Depression, in 1928, this ratio was 17.6%; in 1932, this ratio increased to 21.4%. Since there are always many more advertisements for women than advertisements for men, the improvement by 3.8% was not insignificant. In addition, I found that men’s products were usually much more expensive than women’s. At a time when purchasing power was weak, advertisers obviously wanted to attract people to buy more men’s products in an effort to make more money from high prices rather than high quantity sold. Such a trend may seem a bit confusing, but given the economic situation, such a development seems economically logical.

Hair care and hair products remained important throughout the depression. Seattle Times Nov.17, 1931. Collected by Anna Wong Finally, my analysis of advertisements in The Seattle Times found a very interesting gender disparity: the gap in advertising between women’s products and men’s products became smaller. If we divide the sum of advertisements for men’s fashion and men’s products by the sum of advertisements for women’s fashion and women’s products, we get a ratio of advertisements for men vs. advertisements for women. Before the Great Depression, in 1928, this ratio was 17.6%; in 1932, this ratio increased to 21.4%. Since there are always many more advertisements for women than advertisements for men, the improvement by 3.8% was not insignificant. In addition, I found that men’s products were usually much more expensive than women’s. At a time when purchasing power was weak, advertisers obviously wanted to attract people to buy more men’s products in an effort to make more money from high prices rather than high quantity sold. Such a trend may seem a bit confusing, but given the economic situation, such a development seems economically logical.

Conclusion

Based on advertising trends in The Seattle Times, we can see how the Great Depression affected people’s everyday lives, the social environment, and the economy. From the changes in the number of different kinds of advertisements, we see the different impact that the Great Depression had on different industries: while luxuries like diamonds, cars, fashion, and radios fell, inexpensive luxuries like movies, tobacco, and alcohol gained a wider consumer audience. In a way, this study changed my original view of the Great Depression. It forced people to re-examine their priorities in life and to think more about their future. It changed Americans’ impulsive lifestyle of the 1920s and reminded people that America still needed to value hard work and to try their best to earn a better life.

As I mentioned earlier, my study is certainly very limited: the sample size is small and the randomization is probably less than scientific. However, as I made every effort to base my conclusions on statistical data and historical facts, I believe such an analysis of the advertising trends in The Seattle Times before, during, and after the Great Depression does offer us some valuable insight into this historic event and may enlighten us in some way about how to cope with the present economic crisis and prepare for future economic hardships.

Copyright (c) 2009, Yifeng Hua

HSTAA 105 Winter 2009