by Stephanie Fajardo

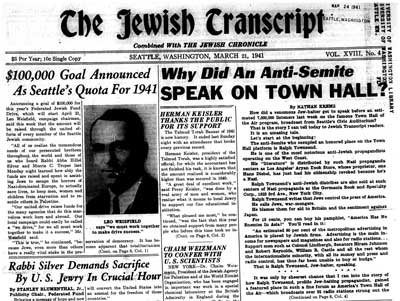

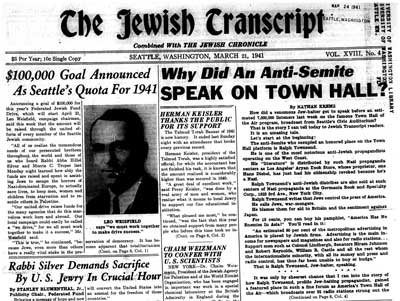

Seattle's Jewish Transcript newspaper sought many interralated strategies in response to anti-semitism. The paper publicized and argued against anti-semitic attacks, as in this March 21, 1941 issue; claimed Jewish identity as an American identity; and argued that Nazism was an American, not just "Jewish," problem. Click photo to enlarge.

In the United States during the Great Depression, anti-Semitism pervaded cities with small Jewish populations.[1] In the Pacific Northwest anti-Semitic discrimination was very common, and instances of it were often reported by Seattle's Jewish community newspaper, The Jewish Transcript. The Transcript also focused much of its attention on different aspects of the Jewish struggle for equality, centering around the desire to be accepted as true Americans. The Jewish Transcript argued that Jews had been central to the nation’s founding and civic culture, and used specific language, stories, and narrative practices in making that case.

Throughout the 1930s anti-Semitism continued to affect Jewish life in the Seattle area. The local public generally viewed Jewish people as different, un-assimilable, and threatening. The Transcript consistently rejected these beliefs, arguing that anti-semitism was inherently "anti-American." Notably, the paper emphasized this question of American values rather than the immorality of such discrimination. In doing so, they attempted to associate the local Jewish population with Americanism, defining American as an identity and society with a rich tradition of Jewish influence. These attempts reveal how Jewish Seattleites defined American pluralism to include the Jewish people, culture, and religion. They sought to demonstrate that Jews did not need to deny their heritage, as nativists had claimed, in order to be considered Americans; rather, the Transcript argued, there could be no “American” identity without Jewish people.

Seattle's Jewish community had been built in three waves. In small numbers, German-speaking Jews had been present in the early days of the city. They were joined after 1900 by Eastern European immigrants and also by a significant population of Sephardic Jews from Rhodes, Turkey, and the eastern Mediterranean. In 1924, Seattle native Herman Horowitz launched the Jewish Transcript to give the community a weekly newspaper.

He pledged to “advocate the highest ideals of Judaism, linked with the most strenuous Americanism.”[2] The newspaper contested anti-semitism in its early years, but as Hitlerism raised the stakes in the 1930s, the Transcript became increasingly vocal.[2.5]

The 24th Avenue Market, at 2401 Yesler Way, was a hub for Seattle's sephardic community. This picture, from 1941, shows the vibrant community that was sustained during the Depression, through synagogues and small Jewish-owned businesses. From left, owner Sam and Isaac Maimon, Rachel Habib, and Al Azose. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections.)

A 1939 article in the Transcript titled "Menace of Anti-Semitism In U.S. is Abated By Intelligent Action" explained some of the common methods of anti-Semitic propaganda.[3] The article states that these methods could be "simply classified." Jews were identified with the most controversial social and political positions at the time. Jews were linked to communism, the conspiracy of the Elders of Zion, the economic crisis, the New Deal, assertions that large corporations were controlled by Jews, and Negro domination.[4] These sorts of associations clearly depended on one's political views, though many were billed as being anti-American, which also clearly demonstrates how being “American” meant a particular race, color, and political proclivity.

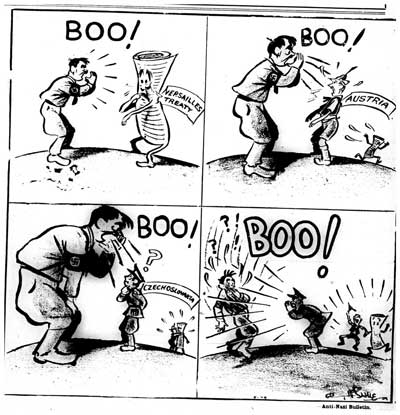

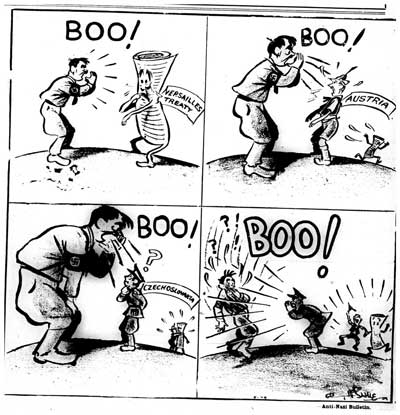

This cartoon, from July 15, 1938, celebrates the defeat of Hitler and Nazism. Part of the Transcript's strategy for countering anti-semitism was to take a clear political stance in line with American foreign policy. The Transcript sought to define the "Jewish problem" as an "American problem," and Hitler's threat as a threat to American and free European ways of life. Click on the image to enlarge.

In return, the Transcript often published articles that associated anti-Semites with some of the same anti-American notions that they had charged Jews with. For instance, one article in particular focused on how an anti-Semitic campaign, which was actually occurring in Canada and not the U.S., was set in motion by Fascists.[5] The article implied that anti-Semites and their beliefs should not have been taken seriously, as their association with Fascism clearly defined them as the enemy not just to Jews but to America as a whole. These types of associations, which marked anti-Semites with some sort of anti-American or un-democratic value, were quite common.

Most of the paper's responses to anti-Semitic claims, though, focused on uplifting the Jewish community. The paper's most common approach to addressing the issue of anti-Semitism was actually to portray what had been perceived as the "Jewish problem" as a clearly defined American problem. A common implication was that anti-Semitism de-moralized American society. As one article claimed, "[anti-Semitism] strikes at the very roots of the religious faith of civilized men."[6] Another conclusion was that anti-Semitism would surely "destroy the moral and political unity" of Americans, and would therefore threaten democracy.[7] In this argument, the paper created an effectually “American” polemic, one that sought to integrate Jews and Jewish influence with the whole of the American cultural and political heritage. Interestingly, these arguments seem always to emphasize the fact that anti-Semitism de-valued American society at large rather than focusing solely on the sufferings of American Jews, strengthening the connection between Americanism and Jewishness.[8]

In addition to addressing the Jewish "problem," the Transcript also responded to anti-Semitic claims by marking the importance of Jewish participation in seminal American traditions and of a long Jewish presence in American history. In printing articles describing the “Discovery of America,” the first Thanksgiving, or the 1787 convention of the Federal Constitution, the Transcript was making an implicit claim to American history as their own.[9] The paper also featured descriptions of Jews with great personalities of American history.[10] The Transcript repeatedly tells of Benjamin Franklin and Abraham Lincoln befriending Jewish persons. The paper argued that Lincoln, if “alive today,” would have been a great friend of the Jewish people.[11] Another article states that Lincoln’s political coterie intermingled with the B’Nai B’Rith, a Jewish service organization. It seems that the paper was trying to weave Jewish people into the cultural and political narrative of the country in order to prove the importance of the Jewish community in American society, and defend their natural fit within it.

Consonant with such efforts, the Transcript also advocated for the place of Jewish history in American textbooks. In particular, editorials in the paper argued that American schoolchildren should have been made aware of the many “sacrifices” and “contributions” made by Jews to both world and American history. In this argument too, the paper seems interested in trying to protect the place of Jews in America and the world as well as broaden the conceptions of Americanism for non-Jews. While nativist propaganda intended to denigrate the Jewish community by a variety of means, Jews in Seattle were turning to other forms of narrative to protect their place in American society.

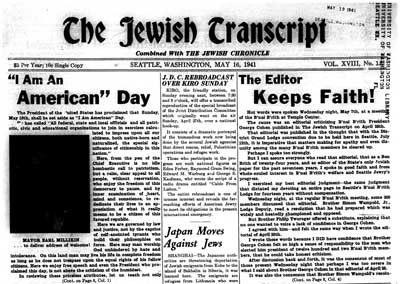

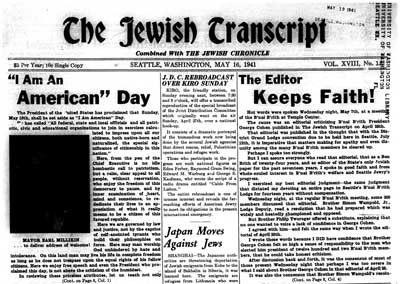

The front page of the Transcript on May 16, 1941, proudly celebrated the new "I Am an American Day," part of a strategy of claiming Jewish identity as an intrinsically American one. Click the image to enlarge.

As part of their claim to American history and present-day community, the Transcript emphasized Jewish participation in American civic culture. On May 16, 1941, the main article on the front page reported on "I am an American Day," a holiday that the president had recently created. The Transcript's article encouraged Jews to participate and stressed the importance of celebrating the American values of "freedom" and "equality."[12] Another article discusses an upcoming election and, arguing against popular stereotypes, reminding its readers that Jews were not politically powerful. In fact, the Transcript claimed, Jews were actually very divided when it came to politics. They were, in other words, not one cohesive block but rather, like all Americans generally, their unity was rooted in democracy.[13]

The deliberate association of the Jewish community with American civic culture suggests that Jews had been Americans all along. Seattleite Jews who possessed the qualities of Americanism, defined by understanding of and devotion to civic duty, questioned how they were to assimilate. Regardless of existing social discriminations, Jewish people in Seattle during the 1930s understood that the American legal system had been designed to include people of different racial, ethnic, and religious backgrounds. Their attempt reflects their desire or willingness to achieve acceptance within American society through a variety of means without denying their Jewish identity.

In correlation with civic duty, the Jewish community attempted to validate their claim to inclusion in America by proving their patriotism. This argument was punctuated first and foremost with declarations of military service. Between 1939 and 1941, The Transcript cites myriad case studies that confirm the service of Jewish American soldiers in the country’s military conflicts. The role of Jews in WWI is especially well covered in the paper. Additionally, the historical duration of Jewish service features prominently in several articles. As one 1941 article declared in its title, “Jews Have Always Served in US Defense in All Wars.”[14] Several articles issued in subsequent months echo this sentiment almost exactly.

Such articles seemed to have functioned for two polemic purposes. Firstly, the Jewish Transcript appears to propagate positive images of Jewish American patriotism, thereby emphasizing the place of Jewish people in America. One 1940 article communicates this in unambiguous terms, asserting that “Jews are an essential part of America… as citizens among us, they have always done their full part… when the time came to serve their country under arms, no class of people served with more patriotism.”[15] Significantly, a non-Jewish speaker is cited. The article not only seeks to verify Jewish contributions, but also highlights the apparent indisputability of Jewish service to America as simply the service of an American to America.

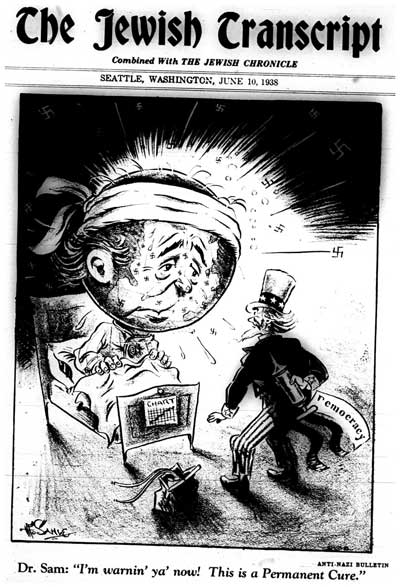

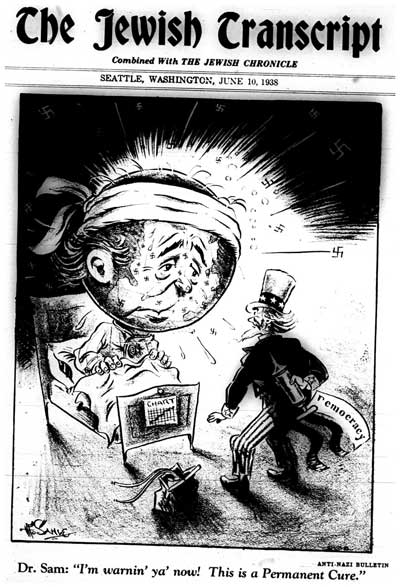

Uncle Sam is pictured injecting the sick world with the cure of democracy. Thus the problem of Nazism and anti-semitism was seen as a worldwide not simply Jewish, problem, one only America could fix. ( March 10, 1938.) Click the image to enlarge.

These articles also function with a more symbolic capacity. That is, the Jewish Transcript not only advocated that Jews were loyal and patriotic Americans, but were citizens wholly dedicated to the nation’s core political precepts. The paper published articles titled “Jews Never Fail to Fight for Democracy and Justice” or “Faith in Democracy Vital to American Defense.”[16] Other articles spoke of the Jewish role in defending and creating the United States. “The [service] of Jews,” the paper maintained, had been “crucial” to “centuries of American History” and even influential in the American Revolution.[17] As one report articulated, the service of Jews to America had been “laudable from the Birth of the Republic.”[18] These statements evince how Jews sought to be included in the “American sphere” by emphasizing their continual presence in the nation’s history as well as their veneration to that nation’s philosophical mantra. In effect, the Jewish Transcript was attempting to make quantifiable the stake that Jews had in “America” as a nation as well as a paradigm of cultural and political values.

Overall, the Transcript's responses to anti-Semitism suggest that Seattleite Jews viewed themselves as already being part of the "American" conglomerate. They only needed to prove to the rest of America that this was true. Seattleite Jews argued that nativists represented a myopic America, one that actually contradicted what it meant to be American. Americanism, according to the Transcript, necessarily included peoples of different cultures, religions, and ethnic backgrounds. American principles and beliefs such as civic duty, freedom, and equality were to unite all American peoples. Seattleite Jews recognized this and sought to demonstrate that nativists were essentially re-defining, narrowing, and betraying Americanism in their refusal to accept the Jewish community as part of their own.

In their responses, the Transcript also questioned the nature of American democracy. Seattleite Jews mostly spoke English, were in many cases American citizens, and were educated within the American school system. However, they were excluded from the benefits of being socially and politically recognized as full Americans. The Transcript pointed out this contradiction. Although Seattleite Jews may have thrived in American society, and contributed to it like all other peoples, they were still required to prove their loyalty and fight for their status as "true" Americans, using a variety of innovative and narrative strategies to do so.

Copyright (c) 2010, Stephanie Fajardo

HSTAA 105 Winter 2010

[1] Ruppin, Arthur,

The Jews in the Modern World: with an introduction by L.B.Namier, (London Macmillan and Co. 1934), 26; Hamerow, Theodore S.,

Why We Watched: Europe, America, and the Holocaust, (W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY 2008).

[2] Rachael Blanchard,

"The Jewish Transcript, 1924-1926," Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project

[2.5] Editors Note: This paragraph has been changed since the essay was originally published.

[3] "Menace of Anti-Semitism in U.S. is Abated By Intelligent Action,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Feb. 3, 1939), 6.

[4] Ibid, 6.

[5] "Anti-Semitic Campaign Is Being Waged in Canada By Fascists,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Aug. 18, 1939), 7.

[6] "Catholics And Protestants Receive Gift,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Jan. 12, 1940), 6.

[7] "No Divided Loyalty!,"

The Jewish Transcript, (April 28, 1939), 9.

[8] Consult the following: "Anti-Nazi Bulletin,"

The Jewish Transcript, (June 10, 1938), 3; "Democracy Cannot Sell Humanity Down The River of Nazi Tyranny,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Feb. 3, 1939), 7; "Christians in United States Cooperate in Battle Against Nazi Persecution Of Jews,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Feb. 3, 1939), 7; "Fighting Nazis Is Not Alone A Jewish Issue,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Feb. 3, 1939), 3; "Make Freedom An Uncontested Fact In United States Democracy,"

The Jewish Transcript, (July 7, 1939), 5; "Senator Schwellenbach Declares Jews Must Fight For Democracy,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Oct. 27, 1939), 3; "Catholic, Protestant And Jewish Faiths To Be Represented At Meeting Jan. 12,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Jan. 5, 1940), 1; "The Challenge to Democracy,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Aug. 16, 1940), 2; "In 'The Great Hatred,' Anti-Semitism Is Held As An Evil Process Affecting All Races And Creeds,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Dec. 6, 1940), 6; "Ben Gurion

demands American Unity,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Jan. 31, 1941), 2; "Corrupting American Morale,"

The Jewish Transcript, (July 18, 1941), 2.

[9] "Bill of Rights Rounded Out The Constitution of Nation,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Dec. 12, 1941), 1; "America's First Thanksgiving,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Nov. 24, 1939), 2.

[10] "In The Campaign To Educate The Public Jewish History Should be Told In Text Books,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Feb. 17, 1939).

[11] "If Lincoln Were Alive Today!"

The Jewish Transcript, (Feb. 10, 1939), 1.

[12] "'I Am An American' Day,"

The Jewish Transcript, (May 16, 1941), 1 and 8.

[13] "The Mythical 'Jewish Vote!"

The Jewish Transcript, (May 10, 1940), 2.

[14] "Jews Have Always Served in U.S. Defense In All Wars Report Shows,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Aug. 8, 1941).

[15] "American Jewry's Record In World War No.1,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Nov. 29, 1940), 2.

[16] "Grand Lodge 1940 Session Ended in Patriotic Fervor,"

The Jewish Transcript, (July 26, 1940), 1; "Jews Never Fail to Fight For Democracy and Justice,"

The Jewish Transcript, (December 12, 1941), 6.

[17] "Massachusettes Gov. Lauds Jews For Service From Birth Of Republic,"

The Jewish Transcript, (Aug. 16, 1940), 6.

[18] Ibid, 6.